Risk Factors for the Development of Urinary Tract Infection During Pregnancy Caused by Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria

Murillo Llanes Joel1, González Ibarra Fernando P2, Mora Palazuelos Carlos3, Darr Jason4, Garzón López Oscar5, Flores Gaxiola Adrián6, Arun Kumar Avinashi S2 and Osuna Ramírez Ignacio7*

1Department of Research, Sinaloa Health Services, Women’s Hospital, Mexico

2Department of Medicine/Hospitalist, Banner Del E. Webb Medical Center, US

3Laboratory Service, Sinaloa Health Services, Women’s Hospital, Mexico

4Alabama College of Medicine, US

5Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Sinaloa Health Services, Women’s Hospital, Mexico

6Department of Infectiology, Women’s Hospital, Mexico & Faculty of Medicine, Autonomous University of Sinaloa, Mexico

7Public Health Research Unit, Faculty of Chemical-Biological Sciences, Autonomous University of Sinaloa, Mexico

Submission: February 17, 2021; Published: November 08, 2022

*Corresponding author: Osuna Ramírez Ignacio, Boulevard Cantabria y Rio Deva 2338-10, Fraccionamiento Stanza Cantabria, Culiacán, Sinaloa, México

How to cite this article: Murillo L J, González I F P, Mora P C, Darr J, Garzón L O, et al. Risk Factors for the Development of Urinary Tract Infection During Pregnancy Caused by Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamase Producing Gram-Negative Bacteria. JOJ Case Stud. 2022; 13(5): 555875. DOI: 10.19080/JOJCS.2022.13.555875.

Abstract

Background: Antimicrobial resistance is increasing worldwide, previous hospitalizations and use of antibiotics are well known risks factors for the development of urinary tract infections causedby gram-negative beta-lactamase producing bacteria, however, we know little about this problem during pregnancy.

Objective: To determine the risk factors for the development of urinary tract infections caused by extended spectrum beta lactamase producing gram-negative bacteria during pregnancy.

Methods: A case-control study was performed in 336 pregnant women with urinary tract infections caused by extended spectrum beta lactamase (ESBL) producing gram-negative bacteria and alsonon-producing extended spectrum beta lactamase gram-negative bacteria treated at the Women’s Hospital in Culiacan, Mexico, between February 2019 and January 2020. Logistic regression was used to calculate odds ratio (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI).

Results: The risk factors were recurrent urinary infection (OR = 1.84; 95% CI: 1.01, 3.34), Ceftriaxone administration (OR = 2.10; 95% CI: 1.01, 4.39), previous hospitalizations (OR = 4.03; 95% CI: 2.04, 7.93).

Conclusion: The risk factors for urinary tract infections caused by extended spectrum beta lactamase producing gram-negative bacteria during pregnancy were previous hospitalizations, administration of ceftriaxone, and recurrent urinary tract infections.

Keywords: Risk factors; Urinary tract infections; Pregnancy; Escherichia coli; Beta-lactamases

Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTI) are one of the most frequent complications during pregnancy after anemia of pregnancy, however, urinary tract infections can affect both maternal and perinatal health, as well as the evolution of pregnancy [1]. The indiscriminate use of antibiotics, together with the increased mobilization that occurs in human populations, facilitates the spread of multi-resistant bacteria, particularly the extended-spectrum beta-lactamase (ESBL) producing Escherichia Coli (ESBL+E.coli) [1,2].

During pregnancy, urinary tract infections are common due to normal physiological changes. One of the most important changes during pregnancy is induced by the relaxing properties on the smooth muscle that progesterone possesses. In addition, the physiological hydroureter and decrease in bladder tone are both natural phenomena that double the total capacity of the urinary tract without causing discomfort or voiding urgency. However, this favors bacterial colonization in pregnancy [3].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), UTI in pregnancy is an infectious process that results from the invasion and development of bacteria in the urinary tract that can bring about maternal and fetal repercussions [4], and the presence of UTI in pregnancy is one of the most common complications worldwide. The incidence of urinary infections in pregnant women is about 150 million cases per year. In Spain, the prevalence is 5-10% and in Mexico it is reported at 2% with a recurrence rate of 23%. Its incidence is estimated at approximately 5-10% of all pregnancies, although usually it is asymptomatic bacteriuria (AB). Furthermore, sometimes symptomatic clinical processes can develop such as cystitis and pyelonephritis [5].

ESBL+ E. coli infection has become widespread in hospitals around the world. The ESBL strains represent an example of the ability of gram-negative bacteria to develop new mechanisms of resistance to new antimicrobial agents and the highest rates are 47% in India [6], Latin America and Asia, with respect to countries such as Europe and North America. In a study in Colombia, Community acquired UTI due to ESBL+ E. coli presented a prevalence that fluctuated between 12.5% to 34.58% [7], in Mexico an incidence of 48% has been reported, and in the Women’s Hospital in Culiacan, Sinaloa, Mexico during 2013, an incidence of 12.5% in UTI caused by ESBL+ E. coli was reported [8-10].

ESBLs are transferable enzymes of rapidly evolving plasmids that confer unique patterns of resistance to antibiotics in various bacterial species. Some risk factors for the development of UTI due to enterobacteria have been identified, such as a history of infection with an ESBL producing microorganism, recent use of antimicrobials, recent hospitalization, and a history of metastatic cancer. These infections are increasingly common in the obstetric population, gynecologists do not widely recognize the problems related to ESBLs and also know little about the factors that are associated with the development of UTI caused by ESBL+ gram-negative organisms in pregnancy. Consequently, there are controversies about the diagnosis and treatment of these patients.

It is well known that the presence of infections with strains that produce ESBL are related to higher mortality, longer hospital stays, higher hospital expenses, alongside decreased rates of clinical and microbiological response [6,7].

The objective of this study was to identify the factors associated with the development of urinary tract infections caused by betalactamase- producing gram-negative organisms during pregnancy, the secondary objective was to identify antibiotics useful in pregnant women with urinary tract infections caused by gram gramnegative organisms.

Methods

Study subjects

A case-control study was conducted in pregnant patients diagnosed with urinary tract infection in the period from February 1, 2019 to January 30, 2020, evaluated in the outpatient consultation area, emergency department, and the inpatient area of the Women’s Hospital in Culiacan, Sinaloa, Mexico. The present investigation was evaluated and approved by the Hospital Research Committee. The clinical files that were obtained from the patients were strictly stored in total confidentiality in accordance with the Federal Law for the Protection of Personal Data Held by Individuals.

The cases were pregnant patients with urinary tract Infections caused by ESBL-producing gram-negative bacteria and the controls were pregnant patients with urinary tract infections caused by non-ESBL-producing gram-negative bacteria.

Urinary tract infection was defined in pregnant patients with suggestive clinical manifestations such as low back pain, dysuria, increased urinary frequency, bladder tenesmus, urgency, nocturia and/or signs of fever, pain on palpation of the lower abdomen, pain on percussion of the lumbar area, gross hematuria with at least two of the following findings in the urinalysis: pH greater than 6.5, positive leukocyte esterase, positive nitrites, white blood cell count greater than 10 cells per field, bacteriuria greater than two (++), and the presence of erythrocytes. Exclusion criteria for this study included patients with urine cultures positive for other bacteria, non-pregnant patients, immunocompromised patients, patients with a single kidney, and previous nephrolithiasis. Elimination criteria were incomplete chart, poor/incorrect collection of the urine sample, or urine sample unsatisfactory of the quality controls to the laboratory.

Procedure for collection of urine samples

The sample was taken from the first urination in the morning, hands washed beforehand with soap/water, rinsed with water, then dried, and the labia kept separated until the urine sample was completely collected. The patient was instructed to urinate by discarding the first 20-25mL. After which, and without interrupting urination, the rest of the urine was collected in a sterile container [11].

Urine culture

Urine culture was considered positive when an organism was found and the colony count was greater than more than 100,000 colony forming units (CFU) / mL of a single uropathogen. The frequency and type of microorganisms isolated in the urine culture were analyzed, as well as the antimicrobial susceptibility pattern.

Culture and identification of gram-negative bacteria

Samples were grown on blood agar and MacConkey agar, then incubated for 24 hours at 37°C. Subsequently, the macroscopic characteristics of the colonies (shape, size, pigment production, and smell) were observed. Positive urine cultures were tested for susceptibility to 25 antibiotics using the automated Micro Scan Walk Away 96SI system, following the manufacturer’s instructions. The strains were considered resistant according to the minimum inhibitory concentration as indicated by the interpretation criteria of the National Committee of Clinical Laboratory Standards, likewise, the presence of beta-lactamases was identified. [12] To confirm the bacterial identification, biochemical tests were performed (API E20, Bio Mérieux, Durham, NC, USA).

Statistical analysis

A descriptive analysis was carried out to obtain frequencies and percentages in qualitative variables and quantitative variables we estimatethe mean and standard deviation (SD).

In the inferential analysis for quantitative variables with non-Gaussian distribution the Kruskal-Wallis statistical test was applied, and in the patients with Gaussian distributon the Student t-test was used for the comparison of means. p-values less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. The odds ratio (OR) was obtained through the application of logistic regression analysis and their respective 95% confidence intervals, using the statistical program Stata SE 13. College Station, Texas 77845 USA.

Results

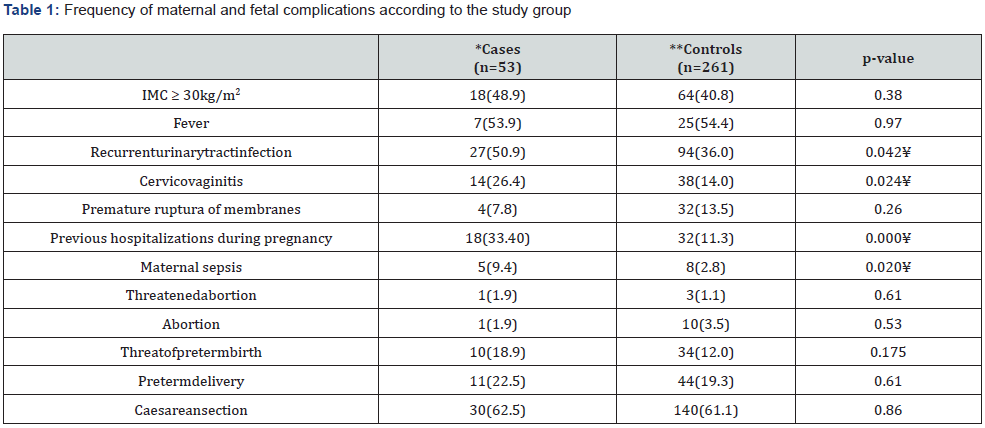

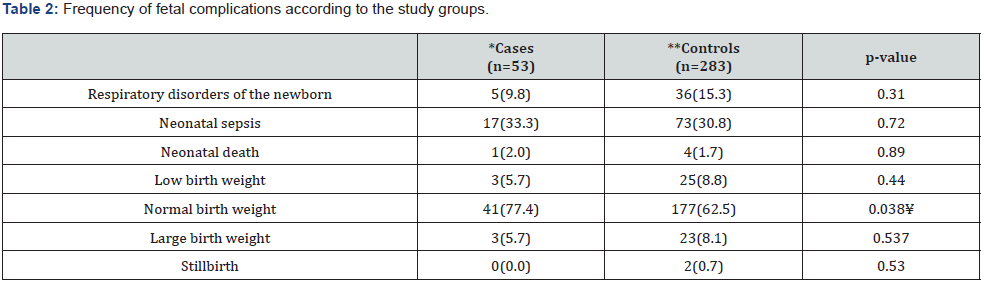

A total of 336 patients, the mean age was 24.8(SD=6.8) years (minimum of 14 and maximum 46); the age was not different between the study groups, p=0.87. The gestational age was 38.2(SD=2.4) weeks of gestation (minimum, 23.3 and maximum,42), without difference between the groups, p=0.94; the days of hospital stay were 2.08 (SD=1.5) days (minimum, 1 and maximum, 31), without differences between the groups, p=0.37; the mean birth weight was of 3,184 (SD=596) grams, (minimum,1200 and maximum, 4,160), without difference between the groups, p=0.86. The 27.1% (n=91) patients were teenagers, 28 (8.3%) were older than 35 years, 112 (33.3%) were primigravids and 22 (66.7%) were multigravids. According to the gestational age, 55 (16.3%) were preterm births, 283 (83.7%) were term. The frequency of maternal and fetal complications according to the population studied are described in Table 1 & 2.

UTI: Urinary Tract Infection; *UTI due to ESBL producer/positive gram-negative; **UTI due to ESBL non producer/negative gram-negative. ¥ Statistically significant 5%.

*UTI due to ESBL producer/positive gram-negative; **UTI due to ESBL non producer/negative gram-negative. ¥ Statistically significant 5%.

The total of urine cultures, 232 (69.1%) developed Escherichia coli, 57 (17%) developed klebsiella pneumoniae and 19 (6.6%) were proteus mirabilis of which 19.8, 10.5, and 5.2% were producers of ESBL respectively, the rest 28 were non-ESBL producing organisms.

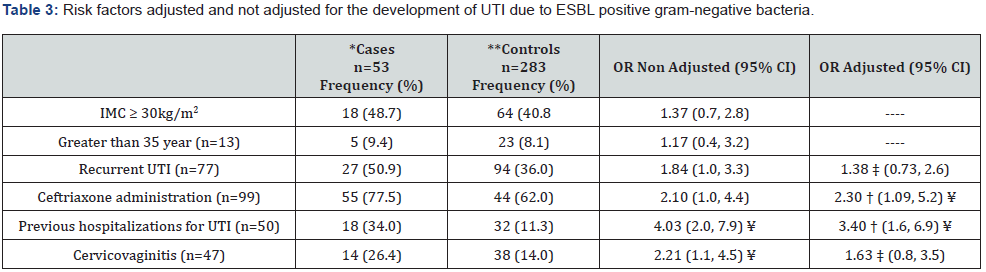

The risk factors non-adjusted for the development of UTI in pregnant women caused by ESBL+ gram-negative bacteria were: Recurrent UTI (OR=1.84; 95% CI: 1.01-3.34), Ceftriaxone administration (OR=2.10 95% CI: 1.01-4.39) and previous hospitalizations (OR=4.03 95% CI: 2.04-7.93), a complete description is shown in Table 3.

*UTI due to ESBL positive gram-negative; **UTI due to ESBL negative gram-negative; ⁂: Source: 2016 Women’s Hospital Database: † = Adjusted for recurrent UTI; ‡ = Adjusted for previous hospitalizations. ¥ Statistically significant 5%.

The antibiotics administered for UTI were cephalexin in 102 cases (71.8%), ceftriaxone in 99 cases (69.7%), and gentamicin in 53 cases (37.3%). Those who were treated with cefotaxime and ceftriaxone were associated with the presence of ESBL in 80% of cases and in 51.5% of cases, respectively.

Discussion

It is well known that there is a high risk of infection and colonization by strains that produce ESBL in patients with prolonged hospital stay or who required invasive devices. The previous use of antibiotics and previous hospitalizations are also risk factors. ESBLs are found in enterobacteria, mainly Klebsiella sp. and E. coli, which implies resistance to antibiotics such as penicillin, cephalosporin, and aztreonam [1].

In Europe and the United States, and to a lesser extent in Asia and South America, an increase in the number of enterobacteria producing ESBL in clinical material derived from hospitalized patients or from those living in the community has been demonstrated [13,14]. In Mexico, the trend of the development of ESBLs at the hospital or community level is unknown, however according to the SENTRY antimicrobial surveillance program in Latin America, strains with low susceptibility to meropenem and imipenem are reported in Mexico with an incidence of 48% [15]. In Latin America, mainly in Argentina, Venezuela, Brazil and Mexico, the most commonly reported beta-lactamases are SHV-5, SHV- 2, and CTX M-2 [16,17].

In a study in Colombia, risk factors for ESBL producing microorganisms infections acquired in the community were: frequency of recent antibiotic therapy, previous hospitalization, presence of high urinary tract infection, as well as the history of recurrent urinary tract infection, chronic kidney disease, and diabetes mellitus [18]. In the present study, we found by univariate analysis that recurrent urinary tract infections cervico-vaginitis, previous hospitalizations due to UTI, and the use of ceftriaxone were non adjusted risk factors for UTI due to ESBL+ gram-negative bacteria. However, when those risk factors were adjusted for the history of recurrent urinary tract Infections, only independent risk factors were found for the use of ceftriaxone and previous hospitalizations due to UTI.

To the best of our knowledge, no studies have been conducted in pregnant women investigating the clinical conditions that favor the development of beta-lactamase generating microorganisms. However, in the present study we demonstrated that previous hospitalizations due to UTI was the main risk factor for the development of UTI due to ESBL+ gram-negative bacteria. We observed that in this group, cervico-vaginitis and recurrent urinary infections occurred in 36% and 69% of cases, respectively, which are conditions that favor bacterial development, if the conditions are not hygienic, patients of low socioeconomic status, have deficient diet (mainly iron), immunosuppression, or premature rupture of membranes are conditions that also favor the development of infectious processes that, when treated with third-generation cephalosporins indiscriminately, they could favor the development of extended spectrum beta-lactamases (ESLB).

In this regard, the frequency of vaginosis or cervico-vagnitis occurred in 33% of the cases and the coexistence of with UTI was 63% of the cases, similar to that reported by Escobar-Padilla B et al. [19] in where the coexistence was 40.8%, highlighting the importance of these pathologies, which should definitely be treated urgently [19].

On the other hand, considering E. coli as the causal agent of vaginal infection has been controversial, however, there are studies that report that the isolation of E. coli strains is 4.7 times more frequent in cases of vaginosis than in controls without vaginosis, which would imply the transfer of this bacterium to the fetus or the newborn and, if in addition, an inadequate treatment is administered with cephalosporins of third generation, this may favor the presence of ESBL [20,21].

Age over 35 years was not a risk factor for urinary tract infection caused by ESBL+ gram-negative bacteria and although the frequency of UTI tends to be lower in this group, as the age advances the presence of asymptomatic bacteriuria tends to be increasingly greater, perhaps due to problems of immunological and anatomical type as well as a greater probability of prior exposure to antibiotics [11].

Among pregnant women, the global prevalence of ESBL producing enterobacteriaceae in symptomatic urinary tract infections is different from one geographic region to another, occurring in North America, South America, Europe, Asian countries, India and Africa in 3, 4, 5, 15, 33, and 45% respectively [22]; in our study population 19.8% of the urinary tract infections caused by E. coli were producers of extended spectrum betalactamases and it was lower than those reported by Galindo- Méndez [23], in a study conducted in women in Oaxaca, Mexico where it was reported as 23.4%.This represents a high level of antibiotic resistance to the antimicrobials commonly used, therefore decreasing the therapeutic options available for this vulnerable population [23].

The association between urinary tract infection and preterm delivery has been reported in other studies [10], in the present study, although preterm delivery in patients with UTI caused by ESBL + E coli occurred more frequently, we did not observe a statistically significant association. In a descriptive study conducted in Nicaragua in 168 patients with clinical UTI found in the analysis of antimicrobial resistance in different phenotypic groups of E. coli, showed that 61.5% were resistant to ceftriaxone, 60.7% to cefepime, followed by 68% resistant to gentamicin. An important finding was the presence of E. coli ESBL isolates in 61.5% of the samples, which could indicate the possible appearance of bacterial phenotypes with endemic circulation as potential pathogens in this type of patients. This was mainly found during the third trimester of pregnancy [13].

Many studies have reported restricting the use of thirdgeneration cephalosporins as a successful strategy for decreasing the prevalence of ESBL; the introduction of handwashing and the implementation of contact and disinfection barriers, without the restriction of antibiotics, has contributed to the reduction of ESBLs in the hospital setting. However, the impact has been of lesser magnitude than with the restriction of third generation cephalosporins [24].

The therapy of choice for serious infections focuses on carbapenems, although indiscriminate use should be avoided. In uncomplicated lower urinary tract infections, fosfomycin and nitrofurantoin are the best treatment alternatives [14]. The most effective antibiotics against ESBL+ gram-negative bacteria are carbapenems with 0% resistance, tigecycline with 7.6%, amikacin with 3.7%, nitrofurantoin with 6.7%, and piperacillin/tazobactam with 7.6%, as reported in other studies [25-27].

We found that the antibiotics with higher resistance were generally penicillins, first to third generation cephalosporins with 26%, quinolones 28%, and trimethoprim sulfamethoxazole 63.5%. Similar results as those reported by Mohammed MA et al. [28] in a study conducted in Libya with 1,153 patients with urinary tract infections due to E. coli, including men, women, children, and adults [25,28]. Studies have also revealed an increase in hospital stay and mortality due to the delay in the proper administration of antibiotics. It is important to mention that the patients who were treated with ceftriaxone empirically for UTI, in where the urine culture reported ESBL+ gram-negative bacteria, compared with the control group, were associated with increase in the frequency of preterm delivery, maternal sepsis and neonatal sepsis.

Outbreaks of ESBL+ gram-negative bacteria have been reported in neonatal intensive care units, and thermometers, oxygen probes, liquid soap, ultrasound gel, and health professionals are documented vectors of infection; Eppes, CS, & Clark recommend that laboratories should report the presence of beta-lactamases in urine cultures immediately, that pyelonephritis should be treated with meropenem and cystitis with nitrofurantoin, and that third-generation cephalosporins should be left for complicated or severe cases that have not responded to other limited spectrum cephalosporins [29].

The main strength of the present study is that it constitutes to a certain extent a unique report. To the best of our knowledge, there are no similar reports conducted in pregnant women with UTI due to ESBL+ gram-negative bacteria, and we were able to demonstrate the impact these type of infections may have on the mother, the newborn and fetus, unfortunately, the sample studied was small which makes it difficult to generalized or make strong assumptions or conclusions for this specific population. The development of future research with a larger sample of patients would be relevant. In conclusion, the present study showed that previous hospitalizations, administration of ceftriaxone and recurrent urinary infections in pregnant women may be risk factors for the development of UTI due to ESBL+ gram-negative bacteria.

Funding Statement

This investigation was possible thanks to the budget allocations assigned to the Woman’s Hospital of Culiacan through the Popular Insurance Program.

Acknowledgement

The authors want to thank chemist Verdugo Mendoza Luis Fermin at the research department of Women’s Hospital, Culiacan, Mexico, Myrleth Vega and Jáuregui García Beiry, medical students at the Faculty of Medicine of the Autonomous University of Sinaloa,for their valuable contribution in the preparation of this study, to chemist Elva E. Arce Vargas, and all the staff in the microbiology department of the Women’s Hospital.

References

- Medina PJ, Guerrero RF, Pérez CS, Arrébola PA, Sopeña SR, et al. (2015) Community associated urinary infections requiring hospitalization: Risk factors, microbiological characteristics and patterns of antibiotic resistance. Actas Urol Esp 39(2): 104-111.

- Valdez F, Baca L (2017) Escherichia coli producing extended-spectrum βlactamases (ESBL), a growing problem in our patients. Rev Med Hered 28(3): 139-141.

- Williams W, Andrews LC, Gilstrap LC (2000) Infecciones de vías urinarias. In: Gleicher N (Ed), Tratamiento de las complicaciones clínicas del embarazo. Tercera edición. Buenos Aires, Argentina: Panamericana, pp. 1236-1249.

- Williams (2011) Tratado de ginecología y obstetricia. 23 a. Dallas-Texas: McGraw-Hill Inter American editors. Vol. Cap. 48.2. Organization, world health. WHO recommendations for prevention and treatment, pp. 1033-1038.

- Prevención, diagnóstico y tratamiento de la infección del tracto urinario bajo durante el embarazo en el primer nivel de atención, México: Secretaría de Salud.

- Tumbarello M, Spanu T, Sanguinetti M, Citton R, Montouri E, et al. (2006) Bloodstream Infections Caused by Extended-Spectrum-β-Lactamase-Producing Klebsiellapneumoniae: Risk Factors, Molecular Epidemiology, and Clinical Outcome. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50(2): 498-504.

- Emiru T, Beyene G, Tsegaye W, Melaku S (2013) Associated risk factors of urinary tract infection among pregnant women at Felege Hiwot Referral Hospital, Bahir Dar, North West Ethiopia. BMC Res Notes 6: 292.

- Smaill FM, Vazquez JC (2015) Antibiotics for asymptomatic bacteriuria in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (8): CD000490.

- Gales AC, Castanheira M, Jones RN, Sader HS (2012) Antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negative bacilli isolated from Latin America: results from Sentry Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (Latin America, 2008-2010). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 73(4): 354-360.

- Acosta TJE, Ramos MMA, Zamora ALM, Murillo LJ (2014) Prevalence of urinary tract infection in hospitalized patients with preterm labor. Ginecol Obstet Mex 82(11): 737-743.

- Dautt LJG, Canizalez RA, Acosta ALF, González IF, Murillo LJ (2018) Maternal and perinatal complications in pregnant women with urinary tract infection caused by Escherichia coli. J Obstet Ginecol Res 44(8): 1384-1390.

- Sociedad Española de Ginecología y Obstetricia (2013) Infección urinaria y gestación (actualizado Febrero 2013). Prog Obstet Ginecol 56(9): 489-495.

- Narváez QAM. Patrones Fenotípicos y Resistencia Antibacteriana en aislados de Escherichia coli en Pacientes Embarazadas con Infección Urinaria atendidas en el Hospital Escuela Oscar Danilo Rosales Argüello León, Agosto 2012 – Septiembre 2014” PhD León. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Nicaragua, León Departamento de Ginecología y Obstetricia Facultad de Ciencias Médicas.

- García TA, Gimbernat H, Redondo C, Arana DM, Cacho J, et al. (2014) Extended spectrum beta-lactamases in urinary tract infections caused by Enterobacteria: understanding and guidelines for action. Actas Urol Esp 38(10): 678-684.

- Gales AC, Castanheira M, Jones RN, Sader HS (2012) Antimicrobial resistance among Gram-negative bacilli isolated from Latin America: results from Sentry Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (Latin America, 2008-2010). Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 73(4): 354-360.

- Canto´n R, Novais A, Valverde A, Machado E, Peixe L, et al. (2008) Prevalence and spread of extended spectrum b-lactamase producing. Enterobacteriaceae. Europe Clin Microbiol Infect 14 Suppl 1: 144-153.

- Muro S, Garza GE, Camacho OA, González GM, Llaca DJM, et al. (2012) Risk Factors Associated with Extended-Spectrum ß-Lactamase Producing Enterobacteriaceae Nosocomial Bloodstream Infections in a Tertiary Care Hospital: A Clinical and Molecular Analysis. Chemotherapy 58(3): 217-224.

- Pineda PM, Arias G, Suárez OF, Bastidas A, Ávila CY (2017) Factores de riesgo para el desarrollo de infección de vías urinarias por microorganismos productores de betalactamasas de espectro extendido adquiridos en la comunidad, en dos hospitales de Bogotá D.C., Colombia. Infectio 21(3): 141-147.

- Escobar PB, Gordillo LLD, Martínez PH (2017) Risk factors associated with preterm birth in a second level hospital. Rev Med Inst Mex Seguro Soc 55(4): 424-428.

- Padilla EC, Lobos GO, Padilla ER, Fuentes VL, Núñez FL (2007) Aislamiento de Cepas de Escherichia coli desde casos clínicos de infección vaginal: Asociación con otros microorganismos y susceptibilidad antibacteriana. Rev Chil Obstet Ginecol 72(4): 222-228.

- Watts S, Lanotte R, Meneghetti L, Moulin-Schouleur M, Picard B, et al. (2003) Escherichia coli strains from pregnant women and neonates: interspecies genetic distribution and prevalence of virulence factors. J Clin Microbiol 41(5): 1929-1935.

- Mansouri F, Sheibani H, Javedani Masroor M, Afsharian M (2019) Extended-spectrum betalactamase (ESBL)-producing Enterobacteriaceae and Urinary tract infections in pregnant/postpartum women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Pract, p. e13422.

- Galindo MM (2018) Molecular characterization and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of extended-spectrum β-lactamase-producing Escherichia coli as cause of community acquired urinary tract infection. Rev Chil Infectol 35(1): 29-35.

- Briceño DF, Correa A, Valencia C, Torres JA, Pacheco R, et al. (2010) Actualización de la resistencia a antimicrobianos de bacilos gramnegativos aislados en hospitales de nivel III de Colombia: años 2006, 2007 y 2008. Biomédica 30: 371-381.

- Abujnah AA, Zorgani A, Sabri MA, Mohammady H, Khalek RA, et al. (2015) Multidrug resistance and extended-spectrum β-lactamases genes among Escherichia coli from patients with urinary tract infections in Northwestern Libya. Libyan J Med 10(1): 26412.

- Tasbakan MI, Pullukcu H, Sipahi OR, Yamazhan T, Ulusoy S (2012) Nitrofurantoin in the treatment of extended-spectrum b-lactamase-producing Escherichia colierelated lower urinary tract infection. Int J Antimicrob Agents 40(6): 554-556.

- Tamma PD, Han JH, Rock C, Harris AD, Lautenbach E, et al. (2015) Carbapenem therapy is associated with improved survival compared with piperacillin-tazobactam for patients with extended-spectrum blactamase bacteremia. Clin Infect Dis 60(9): 1319-1325.

- Mohammed MA, Alnour TM, Shakurfo OM, Aburass MM (2016) Prevalence and antimicrobial resistance pattern of bacterial strain isolated from patients with urinary tract infection in Messalata Central Hospital, Libya. Asian Pac J Trop Med 9(8): 771-776.

- Eppes CS, Clark SL (2015) Extended-spectrum β-lactamase infections during pregnancy: a growing threat. Am J Obstet Gynecol 213(5): 650-652.