Adult Pierre Robin Syndrome-Related Difficulties in the Treatment of Sleep Apnea: A Case Report

Yuki Sakamoto*

Department of Dentistry and Oral Surgery, Kansai Medical University Medical Center, Japan

Submission: June 20, 2022; Published: July 08, 2022

*Corresponding author: Yuki Sakamoto, Department of Dentistry and Oral Surgery, Kansai Medical University Medical Center, 10-15 Fumizonocho Moriguchi-shi Osaka, Japan

How to cite this article: Yuki S. Adult Pierre Robin Syndrome-Related Difficulties in the Treatment of Sleep Apnea: A Case Report. JOJ Case Stud. 2022; 13(4): 555870. DOI: 10.19080/JOJCS.2022.13.555870.

Abstract

Most reports of sleep apnea in Pierre Robin Sequence (PRS) patients are for pediatric PRS, with few reports for adults. We report a case of obstructive sleep apnea in an adult patient with PRS that was difficult to diagnose and treat. A 46-year-old female, was referred to our hospital with a complaint of awakening because of respiratory disorder while sleeping. When she was 16 years old, she had undergone otoplasty, mandibulectomy, and bone extension surgery. She had no tonsillar hypertrophy but presented with typical bird-like facies and difficulty in opening the mouth. Imaging findings showed mandibular inferior growth, airway narrowing, bilateral mandibular condyle head deformity, and adhesions between the temporal bone and mandible condyle head. A mono-block type oral appliance was fabricated and patient was recommended to use it, but the airway was not widened with this therapy. We suggested other treatment options, such as surgery, nasal airway tube, and myofunctional training, but the patient refused surgical treatment because of the psychological burden. Therefore, we requested an all-night polysomnography (PSG) test, as a simple sleep test may not accurately capture a patient’s breathing events. The PSG results showed apnea hypopnia index (AHI) of 23.1, indicating that the patient could not get deep sleep because of frequent awakenings caused by hypopnea. Continuous positive airway pressure, which was not indicated in the simple sleep test, was now indicated after the PSG. After three months of using continuous positive airway pressure, the patient’s Epworth sleepiness scale score improved dramatically from 17 to 3 and AHI from 37 to 2.1. We thus concluded that treatment options vary depending on the patient’s episode and background, and the evaluation by performing an all-night polysomnogram is necessary.

Keywords: Obstructive sleep apnea; Pierre Robin syndrome; Continuous positive airway pressure; Polysomnography; Oral appliance

Abbreviations: PRS: Pierre Robin Syndrome; OSA: Obstructive Sleep Apnea; CPAP: Continuous Positive Airway Pressure; RDI: Respiratory Disturbance Index; OA: Oral Appliance; PSG: Polysomnography; AHI: Apnea Hypopnea Index; AASM: The American Academy of Sleep Medicine; EEG: Electroencephalogram

Introduction

Pierre Robin syndrome (PRS) is characterized by micrognathia, glossoptosis, and airway obstruction. Although some cases of PRS in the pediatric population have been reported, few reports discuss the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) in adults with PRS. Surgery has been widely reported as a treatment for PRS in children. The use of a continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is not covered by insurance in Japan if the apnea-(RDI) is less than 40 on a simple sleep test. An oral appliance (OA) is not indicated for patients who cannot move the mandible forward because of temporomandibular joint deformity. Surgery or other treatment options should be considered for such patients. Herein, we report the case of OSA in an adult woman with PRS who underwent jaw surgery in childhood, and her condition was difficult to diagnose and treat.

Case Report

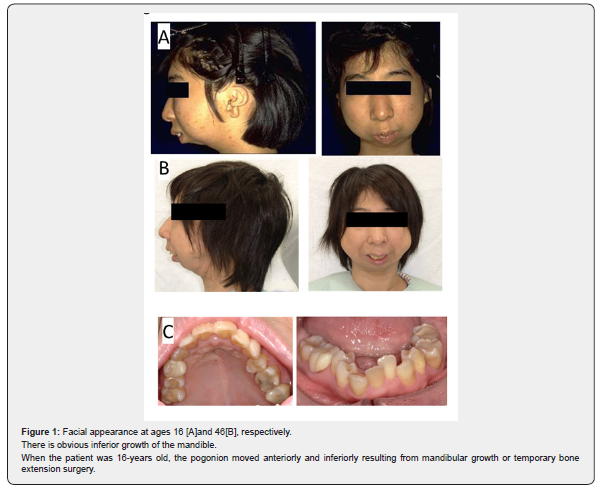

A 46-year-old female visited our otolaryngology department because her family members informed her that she used to stop breathing while sleeping; general fatigue during the day was another concern. The patient was referred to our department after a simple home sleep test. Her medical history included diabetes mellitus (glycated hemoglobin level [HbA1c] 7.6), hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and PRS. Ear and jaw surgery, including otoplasty, mandibulectomy, and bone extension surgery,had been performed by plastic and oral surgeons since the age of16 years. Her physique was normal, with no tonsillar hypertrophy,and she had not reached menopause. She had bird-like facies withdifficulty in opening the mouth (23mm Figures 1A & 1B). Oralfindings included misaligned teeth, stenosis of the mandible, and five missing teeth (Figure 1C).

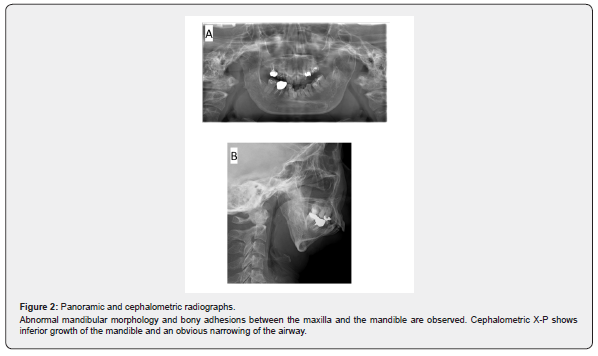

Panoramic radiograph imaging exhibited deformities ofbilateral mandibular condyle and their fusion with the temporalbone (Figure 2A). A cephalometric analysis showed with obviousmandibular undergrowth and a narrowed airway (Figure2B). A simple sleep test was performed at the otolaryngologydepartment; the AHI (apnea hypopnea index) and the Epworthsleepiness scale scores were 37 and 17, respectively

An OA was used as the first-line treatment for the present case;however, the patient was unable to open her mouth (2 lateral fingeropening), and adhesion of the mandible to the maxilla preventedthe forward positioning of the mandible. No airway opening wasobserved using an endoscope (Figure 3). Thereafter, we explainedthe remaining treatment options of surgical therapy, nasal airwaytube, and oral muscle functional training to the patient. However,the patient wanted to avoid surgical therapy owing to the multiplesurgeries she had undergone previously. Therefore, we requestedan all-night polysomnography (PSG) test, as a simple sleep testmay not accurately capture a patient’s breathing events. The PSGtest results showed an AHI of 23.1, arousal index of 28.7, minimumoxygen saturation of 77%, and Oxygen Desaturation Index of 18.7,indicating that the patient could not get deep sleep because offrequent awakenings caused by hypopnea. CPAP, which was notindicated in the simple sleep test, was now indicated in the PSG;as such, CPAP with a nasal mask (Sleepmate, Teijin healthcare Co.Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) was used. The PSG test results with CPAP alsodemonstrated dramatic improvements after three months. Despitethe small sized jaw, a positive pressure for CPAP was achievedby using the nasal mask. After three months, she saw a drastic decrease in her daytime sleepiness and increased physical energy in the morning. When using a CPAP, the Epworth sleepiness scale score decreased to 3, and a dramatic improvement in AHI scorewas observed (2.1).

Discussion

In the present case we reported the effectiveness of usingCPAP in adult patients with PRS related OSA and also indicated that PSG tests must be performed again when simple sleep testsdo not meet the key diagnostic criteria.

Patients with PRS present with micrognathia, tonguedepressions, and consequent airway obstruction, and neonatal respiratory urgency at birth is dangerous. The prognosis isrelatively good if airway management and other interventions are provided at the appropriate time, and if the patient receives appropriate patient education and parent counseling during infancy.

Treatments are tailored to the characteristics and featuresof each patient. Surgery is indicated to improve breathing and feeding and to prevent choking in neonates and infants. Inaddition, surgery is performed for esthetics, mastication, and sleep disorders in childhood. Previously, Goudy et al. [1] foundthat pediatric patients with PRS with cardiac or neurological disease and children who use CPAP or biphasic positive airway pressure require surgical treatment [1]. Adults with PRS who are free of intellectual developmental difficulties are often treatedin childhood, and it has also been reported that the mandible develops and grows with age, resulting in a wider airway [2]. Forthis reason, reports of adults remain rare, and the oldest report of PRS that we have been able to identify is that of a 20-year-old woman by Miller et al. [3] Treatment of sleep apnea in adults with PRS is similar to that for OSA patients in general, and primarilyconsists of using CPAP, which can also be used in patients with micrognathia using a nasal mask. If these criteria are not met, OA,surgery, or other treatment options should be considered. OA may be more effective if the mandible can be forwardly positioned.However, if, as in the present case, mandibular advancement is not possible at all due to adhesions between the jawbone andhave been guided by Stanford University, USA, and are indicated for patients who have dropped out of other treatment modalitiesand patients for whom OA and CPAP are not indicated [4]. Nonetheless, patients with PRS are often operated in childhoodand tend to avoid surgical therapy. As such, patients for whomneither OA nor CPAP is indicated and who do not wish to undergo surgical therapy may use a CPAP at their own expense.

Numerous systemic effects of apnea have been reported.Intermittent hypoxia due to sleep apnea induces inflammation and promotes the pathogenesis of atherosclerotic thrombosis dueto metabolic syndromes. In addition, a correlation between sleep apnea and hypertension, cardiovascular disorders, and diabeteshas been reported [5-7], indicating that sleep fragmentation due to apnea is closely associated with these diseases. Our patientdid not get deep sleep, woke up frequently, and suffered from hypertension, diabetes mellitus, and hyperlipidemia, which mayhave been caused by her sleep apnea.

Sleep test devices are classified into four types, withthe American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) defining Type 1 as PSG, Type 2-4 as portable; Type 2 is capable ofElectroencephalogram (EEG) recording and can be performed at home without an attendant, Type 3 has a minimum of fourchannels, and Type 4 has a minimum of one or two channels. In Japan, simple sleep tests are often carried out by non-specialistsand false-negative results are common. As such, an algorithm has been developed by the AASM to ensure that sleep disordersrequiring treatment are not overlooked by the simple sleep test[8]. In addition to clinical judgment based on a simple sleep test,PSG should also be carried out in patients with sleep disorderrelated symptoms or in light of the presence of complicationsor pre-existing conditions. It has been reported that there was no correlation between the simple sleep test and PSG for mildto-moderate AHI and mild cases tend to be less accurate in a diagnosis [9]. This is due to the fact that PSG can determine sleepduration based on EEG data, electro-oculography, and mentalis electromyography recordings. However, in a simple sleep test, thetime from sleep onset to awakening is considered sleep time, and the time spent awake during the process is also included in sleeptime. Therefore, the AHI tends to be lower in the simplified test given that the sleep time is longer. Therefore, portable devices without EEG are used in combination with actigraphs (small motor volume sensors), and the effectiveness of peripheral arterial bloodflow measurement devices (peripheral artery tonometry) has also been reported [10].

Another reason for which AHI is calculated to be lower with the hypopnea. In Japan, diagnostic criteria are not defined forrespiratory events using a simple sleep test. Therefore, instead of diagnosing hypopnea solely on the basis of decreased respiratoryairflow, only events accompanied by decreased oxygen saturation should be considered, and the diagnostic criteria for hypopneashould be clearly tailored to the Japanese population. In summary, we conclude that the simple sleep test should not be trusted solelyand that patients with sleep-related symptoms and complicated or pre-existing diseases should be diagnosed with PSG.

Conclusion

We report a case of sleep apnea in a patient with PRS who wasdiagnosed with OSA but was not indicated for CPAP on the basis ofa simple sleep test. However, she was subsequently retested with PSG and her condition was found to be favorable for the use of CPAP.

Informed Consent

This case report has the patient’s consent.

References

- Goudy S, Jiramongkolchai P, Chinnadurai S (2017) Logistic regression analysis of Pierre Robin sequence patients requiring surgical intervention. Laryngoscope 127(4): 945-949.

- Kiely JL, Deegan PC, McNicholas WT (1998) Resolution of obstructive sleep apnoea with growth in the Robin sequence. Eur Respir J 12(2): 499-501.

- Miller SD, Glynn SF, Kiely JL, McNicholas WT (2010) The role of nasal CPAP in obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome due to mandibular hypoplasia. Respirology 15(2): 377-379.

- Riley RW, Powell NB, Guilleminault C (1993) Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: a surgical protocol for dynamic upper airway reconstruction. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 51(7): 742-749.

- Savransky V, Nanayakkara A, Li J, Bevans S, Smith PL, et al. (2007) Chronic intermittent hypoxia induces atherosclerosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 175: 1290-1297.

- Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J (2000) Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med 342(19): 1378-1384.

- Lavie P, Herer P, Hoffstein V (2000) Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome as a risk factor for hypertension: population study. BMJ 320(7233): 479-482.

- Collop NA, Anderson WM, Boehlecke B, Claman D, Goldberg R, et al (2007) Clinical guidelines for the use of unattended portable monitors in the diagnosis of obstructive sleep apnea in adult patients. Portable monitoring task force of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med 3(7): 737-747.

- Masa JF, Corral J, Pereira R, Cantolla JD, Cabello M, Blasco LM, Monasteri C, et al (2011) Spanish Sleep Net-work: Therapeutic decision-making for sleep apnea and hypopnea syndrome using home respiratory polygraphy: a large multicentric study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 184(8): 964-971.

- Pittman SD, Ayas NT, MacDonald MM, Malhotra A, Fogel RB (2004) Using a wrist-worn device based on peripheral arterial tonometry to diagnose obstructive sleep apnea: in-laboratory and ambulatory validation. Sleep 27(5): 923-933.