A Case Report on a Rare Cervical Polyp

Ayman Aboda*, Angela Wu, Kimberly Sleeman and Brian McCully

Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Mildura Public Base Hospital, Australia

Submission: February 14, 2022; Published: February 23, 2022

*Corresponding author: Dr Ayman Aboda Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, Mildura Public Base Hospital, Mildura 3500, Victoria, Australia

How to cite this article: Ayman A, Angela W, Kimberly S, Brian M. A Case Report on a Rare Cervical Polyp. JOJ Case Stud. 2022; 13(2): 555858. DOI: 10.19080/JOJCS.2022.13.555858.

Abstract

Background: Giant cervical polyps are rare. They are commonly asymptomatic and diagnosed incidentally on pelvic examination.

Case: This is a 59-year-old multiparous who had a giant cervical polyp diagnosed on speculum examination after presenting to her general practitioner reporting symptoms of pelvic pressure and heaviness. The polyp was successfully resected with hysteroscopy.

Conclusion: A giant cervical polyp in a multiparous female which was successfully resected during hysteroscopy.

Keywords: Giant cervical polyps; Gynecologic pelvic examination; Hysteroscopy; Submucous leiomyoma; Pelvic pressure; Vaginal resection

Introduction

Giant cervical polyps are rarely seen in routine clinical practice. They are defined as being greater than 4 cm in size [1]. Giant cervical polyps protruding outside the vaginal canal can cause diagnostic confusion. They are rarely encountered in gynecologic practice. They are uncommon though can appear in all age groups and in both nulliparous and multiparous women. The incidence is 4-10%. They are most commonly asymptomatic, discovered incidentally at routine gynecologic pelvic examination. Cervical polyps originate most commonly from the ectocervix and are called cervical polyps. More rarely, they arise from the endocervical canal and are called endocervical polyps. Most are less than 2cm in diameter.

Case Presentation

This case report is about a giant cervical polyp in a 59-year-old female, gravida 4 para 3 with three previous normal vaginal deliveries. Her menarche was at the age of 16 and her menstrual interval was 28-30 days with a duration of 3 days. She was menopausal at the age of 48. She became aware of a lump in her vagina 5-6 months prior to presentation to her general practitioner (GP). She reported no vaginal or post coital bleeding and had not been sexually active for some time. The sensation of the lump was most noted when both walking and standing however there were no concerns with bowel or urinary function. She never had cervical screening. She was otherwise in good health apart from hypertension not requiring medications. Her mother had ovarian cancer but there was no other significant family history.

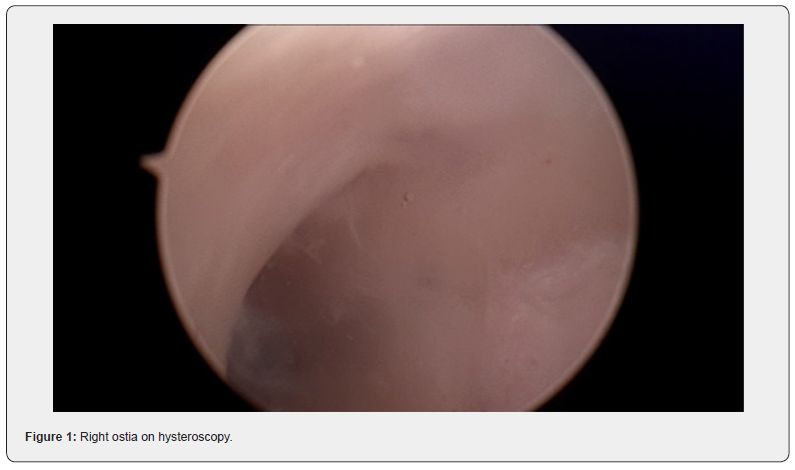

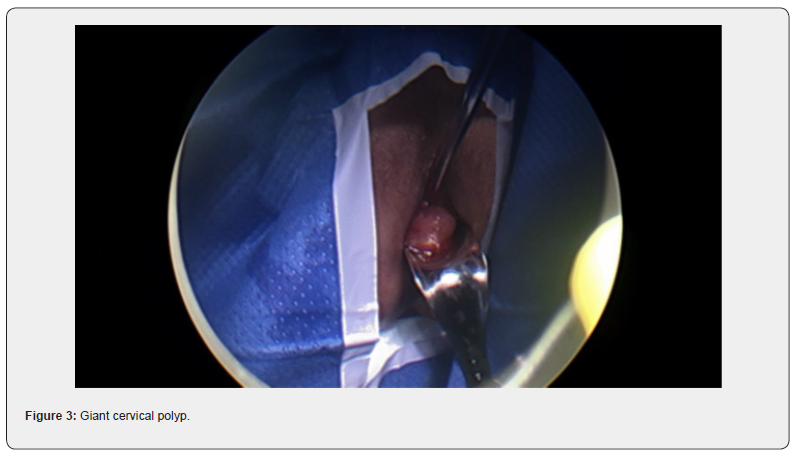

Her GP noted a cervical polyp protruding from the cervix and extending to the introitus. Clear views of the cervix were not possible and cervical screening though attempted, could not be successfully completed. The patient was referred to our service. On speculum examination, a large polyp was again visualized and noted to obstruct clear views of the cervix. Differential diagnosis included cervical polyp or prolapsed fibroid. She was booked for diagnostic examination under anesthesia with hysteroscopy and vaginal resection if possible.

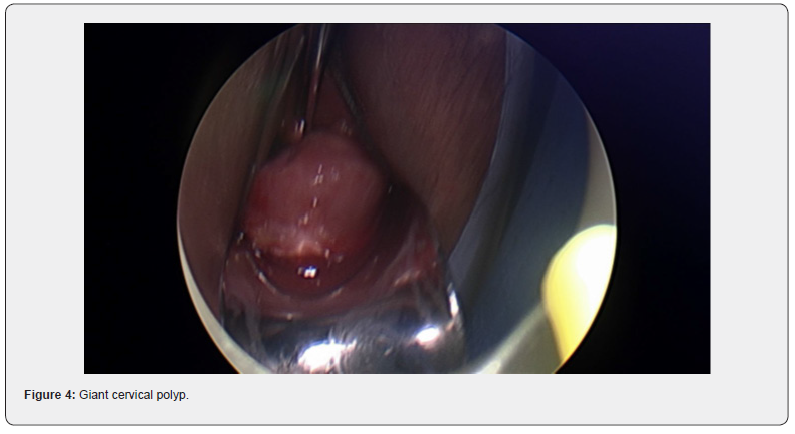

At the procedure, a polyp extending 5 cm beyond the external cervical os was noted, a pedicle was located within the endocervical canal. The cervix was dilated to Hagar number 10 followed by hysteroscopic resection with tissue sent to histopathology. Cervical screening test was completed at the same time. The patient recovered easily and was discharged safe and well the same day.

The histopathology reported a tissue measuring 50x35x25mm with no atypia, necrosis or significant mitotic activity. The conclusion was that the cervical polyp was a submucous leiomyoma. The cervical screening test was negative with recommendation for rescreening in five years.

Discussion

Giant cervical polyps are rare. In this case, the polyp was a fibroid or leiomyoma which had arisen from the endocervix. This is a rare presentation occurring in only 0.6% of cases where pathology has been identified.

Classification of fibroid is according to the involvement of uterine wall, being intramural, sub-serosa and transmural [2]. Cervical fibroids are grouped as type 8, an additional category for leiomyomas not related to myometrium [2].

Diagnosis of fibroid usually start with pelvic examination followed by confirmation on ultrasound which is the gold standard test [3]. MRI could be used to further assess the fibroids to provide information on size, vascularity, location in relation to endometrial cavity and serosa [3]. Hysteroscopy is used to differentiate myoma with polyps, and sometimes an endometrial biopsy is performed at the same time [3]. No radiological investigation was used in this case which is not common. The lesion in this case was intracervical which was found in 22% of the patients in a recently published systematic review [4].

Management of fibroid usually depends on symptoms and preference on fertility preservation. The above-mentioned systematic review on cervical leiomyoma showed that they are most commonly associated with symptoms of abnormal uterine bleeding (44%), followed by volume-related symptoms (20%) such as pressure or the sensation of a lump. Chronic pelvic or lower back pain (14.6%) and chronic urinary complaints (11%) may also occur [4]. Only 7.7% of the patients were asymptomatic [4]. The patient described in this case report presented with bulk-related symptoms only with no other related concerns.

Medical management for symptom relief may include progesterone receptor modulators, tranexamic acid and gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonist [5]. These tend however to be limited by the duration of treatment, with symptoms often returning once intervention has ceased. Surgical treatment may be more successful in providing long term improvement. Procedures include myomectomy, embolization, hysterectomy and hysteroscopic myomectomy [5,6]. Most patients with cervical leiomyoma undergo surgical treatment (88%) with myomectomy, hysterectomy or trachelectomy. In the case described, fertility preservation was not an issue. It was still important however to provide surgical management in the least provocative manner and thus safeguard against risk of iatrogenic morbidity. Hysteroscopic resection was thus successfully performed. There are no citations in the literature reporting similar success in patients presenting in this manner [4].

Conclusion

In conclusion, this was a case of a patient with finding of a large cervical fibroid with mass-related symptoms successfully treated with minimally intrusive, hysteroscopic resection.

Data Availability

Not applicable as this is a case report.

Funding Statement

The research did not receive specific fund but done as part of the employment of the authors, employer is Mildura Public Base Hospital.

References

- Herrmann J, Pallister PD, Tiddy W, Opitz JM (1975) The KBG syndrome-a syndrome of short stature, characteristic facies, mental retardation, macrodontia and skeletal anomalies. Birth Defects Original Article Series11(5): 7-18.

- Morel Swols D, Foster J, Tekin M (2017) KBG syndrome. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 12(1): 183.

- Brancati F, D'Avanzo MG, Digilio MC, Sarkozy A, Biondi M, et al. (2004) KBG syndrome in a cohort of Italian patients. American Journal of Medical Genetics 131(2): 144-149.

- Devriendt K, Holvoet M, Fryns JP (1998) Further delineation of the KBG syndrome. Genetic Counseling (Geneva, Switzerland)9(3): 191-194.

- Dowling PA, Fleming P, Gorlin RJ, King M, Nevin NC, et al. (2001) The KBG syndrome, characteristic dental findings: a case report. International Journal of Paediatric Dentistry 11(2): 131-134.

- Fryns JP, Haspeslagh M (1984) Mental retardation, short stature, minor skeletal anomalies, craniofacial dysmorphism and macrodontia in two sisters and their mother. Another variant example of the KBG syndrome? Clinical Genetics26(1): 69-72.

- Maegawa GH, Leite JC, Félix TM, da Silveira HL, da Silveira HE (2004) Clinical variability in KBG syndrome: report of three unrelated families. American Journal of Medical Genetics 131(2): 150-154.

- Mathieu M, Helou M, Morin G, Dolhem P, Devauchelle B, et al. (2000) The KBG syndrome: an additional sporadic case. Genetic Counseling (Geneva, Switzerland) 11(1): 33-35.

- Novembri A, Franchini F, Calzolari C, Vieri PL, Giovannucci ML (1983) K.B.G. sindrome: revisione della letteratura e presentazione di un caso [K.G.B. syndrome: review of the literature and presentation of a case]. Archivio "Putti" di Chirurgia Degli Organi Di Movimento 33: 423-430.

- Parloir C, Fryns JP, Deroover J, Lebas E, Goffaux P, et al. (1977) Short stature, craniofacial dysmorphism and dento-skeletal abnormalities in a large kindred. A variant of K.B.G. syndrome or a new mental retardation syndrome. Clinical Genetics12(5): 263-266.

- Rivera-Vega MR, Leyva Juárez N, Cuevas-Covarrubias, SA, Kofman-Alfaro SH (1996) Congenital heart defect and conductive hypoacusia in a patient with the KBG syndrome. Clinical Genetics50(4): 278-279.

- Smithson SF, Thompson EM, McKinnon AG, Smith IS, Winter RM (2000) The KBG syndrome. Clinical Dysmorphology9(2): 87-91.

- Soekarman D, Volcke P, Fryns JP (1994) The KBG syndrome: follow-up data on three affected brothers. Clinical Genetics,46(4): 283-286.

- Tekin M, Kavaz A, Berberoğlu M, Fitoz S, Ekim M, et al. (2004) The KBG syndrome: confirmation of autosomal dominant inheritance and further delineation of the phenotype. American Journal of Medical Genetics 130A(3): 284-287.

- Tollaro I, v Bassarelli, Calzolari C, Franchini F, Giovannucci Uzielli ML, et al. (1984) Anomalie dento-maxillo-facciali nella "sindrome KBG" [Dento-maxillo-facial anomalies in the KBG syndrome]. Minerva Stomatologica33(3): 437-446.

- Zollino M, Battaglia A, D'Avanzo MG, Della Bruna MM, Marini R, et al. (1994) Six additional cases of the KBG syndrome: clinical reports and outline of the diagnostic criteria. American Journal of Medical Genetics 52(3): 302-307.

- Kim SJ, Yang A, Park JS, Kwon DG, Lee JS, et al. (2020) Two Novel Mutations of ANKRD11Gene and Wide Clinical Spectrum in KBG Syndrome: Case Reports and Literature Review. Frontiers in Genetics 11: 579805.

- Brancati F, Sarkozy A, Dallapiccola B (2006) KBG syndrome. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases 1: 50.

- Skjei KL, Martin MM, Slavotinek AM (2007) KBG syndrome: report of twins, neurological characteristics, and delineation of diagnostic criteria. American Journal of Medical Genetics 143A(3): 292-300.

- Scarano E, Tassone M, Graziano C, Gibertoni D, Tamburrino F, et al. (2019) Novel Mutations and Unreported Clinical Features in KBG Syndrome. Molecular Syndromology 10(3): 130-138.

- Sirmaci A, Spiliopoulos M, Brancati F, Powell E, Duman D, et al. (2011) Mutations in ANKRD11 cause KBG syndrome, characterized by intellectual disability, skeletal malformations, and macrodontia. American Journal of Human Genetics89(2): 289-294.

- Low K, Ashraf T, Canham N, Clayton Smith J, Deshpande C, et al. (2016) Clinical and genetic aspects of KBG syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics 170(11): 2835-2846.

- Avasthi KK, Muthuswamy S, Asim A, Agarwal A, Agarwal S (2021) Identification of Novel Genomic Variations in Susceptibility to Nonsyndromic Cleft Lip and Palate Patients. Pediatric Reports13(4): 650-657.

- Novara F, Rinaldi B, Sisodiya SM, Coppola A, Giglio S, et al. (2017) Haploinsufficiency for ANKRD11-flanking genes makes the difference between KBG and 16q24.3 microdeletion syndromes: 12 new cases. European Journal of Human Genetics 25(6): 694-701.

- Sirmaci A, Spiliopoulos M, Brancati F, Powell E, Duman D, et al. (2011) Mutations in ANKRD11 cause KBG syndrome, characterized by intellectual disability, skeletal malformations, and macrodontia. American Journal of Human Genetics 89(2): 289-294.

- Lo-Castro A, Brancati F, Digilio MC, Garaci FG, Bollero P, et al. (2013) Neurobehavioral phenotype observed in KBG syndrome caused by ANKRD11 mutations. American Journal of Medical Genetics. Part B, Neuropsychiatric genetics: the official publication of the International Society of Psychiatric Genetics162B(1): 17-23.

- Miyatake S, Murakami A, Okamoto N, Sakamoto M, Miyake N, et al. (2013) A de novo deletion at 16q24.3 involving ANKRD11 in a Japanese patient with KBG syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics 161A(5): 1073-1077.

- Khalifa M, Stein J, Grau L, Nelson V, Meck J, et al. (2013) Partial deletion of ANKRD11 results in the KBG phenotype distinct from the 16q24.3 microdeletion syndrome. American Journal of Medical Genetics 161A(4): 835-840.

- Lim JH, Seo EJ, Kim YM, Cho HJ, Lee JO, et al. (2014) A de novo microdeletion of ANKRD11 gene in a Korean patient with KBG syndrome. Annals of Laboratory Medicine 34(5): 390-394.

- Crippa M, Rusconi D, Castronovo C, Bestetti I, Russo S, et al. (2015) Familial intragenic duplication of ANKRD11 underlying three patients of KBG syndrome. Molecular Cytogenetics 8: 20.

- Monteiro P, Feng G (2017) SHANK proteins: roles at the synapse and in autism spectrum disorder. Nature Reviews Neuroscience18(3): 147-157.

- Chakrabarty B, Parekh N (2014) Identifying tandem Ankyrin repeats in protein structures. BMC bioinformatics 15(1): 6599.

- Ka M, Kim WY (2018) ANKRD11 associated with intellectual disability and autism regulates dendrite differentiation via the BDNF/TrkB signaling pathway. Neurobiology of Disease 111: 138-152.

- (2000) National Research Council (US) and Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Integrating the Science of Early Childhood Development. In: Shonkoff JP, Phillips DA (Eds.). From Neurons to Neighborhoods: The Science of Early Childhood Development. National Academies Press (US).

- Willemsen MH, Vissers LE, Willemsen MA, van Bon BW, Kroes T, et al. (2012) Mutations in DYNC1H1 cause severe intellectual disability with neuronal migration defects. Journal of Medical Genetics49(3): 179-183.

- Poirier K, Lebrun N, Broix L, Tian G, Saillour Y, et al. (2013) Mutations in TUBG1, DYNC1H1, KIF5C and KIF2A cause malformations of cortical development and microcephaly. Nature Genetics45(6): 639-647.