Sigmoid Ectopic Varix Complicating Primitive Biliary Cholongitis Treated by Sclerotherapy

Krati K, Jiddi S* and Benjouad K

Department of Gastroenterology, Mohammed VI University Hospital, Morocco

Submission: January 20, 2020; Published: January 29, 2020

*Corresponding author: Soukaina jiddi, Department of Gastroenterology, University Hospital Med VI, Marrakesh, Morocco

How to cite this article: Krati K, Jiddi S, Benjouad K. Sigmoid Ectopic Varix Complicating Primitive Biliary Cholongitis Treated by Sclerotherapy. 2020; 11(1): 555801. DOI: 10.19080/JOJCS.2020.11.555801.

Abstract

Ectopic varices correspond to the development of collateral circulation outside the oeso-cardio-fundic region. Ectopic rectal varices are the most frequently reported ectopic varices probably because of their ease of diagnosis (4% to 89% of patients with portal hypertension). Their rupture is rare but can be severe.

We report the case of a 51-year-old female patient with primary biliary cholangitis at the stage of cirrhosis. Admitted in our department for intermittent rectal bleeding with deep asthenia, starting 3 months before. A biological test has revealed a hypochromic microcytic anemia. Esophago-gastroduodenoscopy showed the presence of stage II oesophageal varices without red signs associated with portal hypertension gastropathy. A colonoscopy showed an ectopic varix at the sigmoid and the rest of the colonic mucosa was normal. The management of these varices consisted on the ligation of the esophageal ones, while for the ectopic sigmoid varix; a sclerotherapy was performed, by diluting 3cc of Aetoxisclerol with 8cc of 9% saline serum. The procedure was uneventful with absence of rectal bleeding up to 24months of follow-up.

Keywords: Primary biliary cholangitis Sigmoid ectopic varix Rectal bleeding Sclerotherapy

Introduction

Ectopic varices are large portosystemic venous collaterals occurring anywhere in the abdomen outside the oeso-cardial region. They can be located in the small intestine, colon, rectum and enterostomies. Other rarer localizations have been described, particularly in the peritoneum, bile ducts, vagina or bladder [1,2].

Colic varicose veins are a very rare cause of lower gastrointestinal hemorrhage with a reported incidence of 0.07% [3]. We report the case of a sigmoid ectopic varix in a patient with primary biliary cirrhosis successfully treated with sclerotherapy.

Case Report

It’s about a 51-year-old female patient suffering from primary biliary cholangitis at cirrhosis stage. Revealed a year before by a biological cholestasis, confirmed by positive anti-mitochondria type 2 antibodies and positive anti-gp210 antibodies and treated by Ursodeoxycholic acid. The patient was admitted in our department for etiological assessment of an intermittent rectal bleeding. During the interrogation, the patient reported intermittent rectal bleeding of low abundance starting 3 months before her admission. The clinical examination found pallor with conjunctival icterus without other signs of hepatocellular insufficiency. The rest of the exam was unremarkable

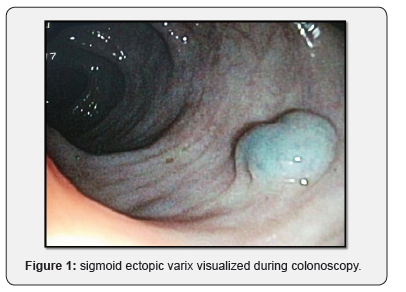

The biological assessment found hypochromic microcytic anemia with 7.2g/dl hemoglobin, with a Ferritinemia at 14ng/ml, platelet count at 226000/ul. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy showed stage II esophageal varices without red signs associated with portal hypertensive gastropathy. Colonoscopy, on the other hand, revealed the presence of an ectopic varix at 30cm of the anal margin (Figure 1), the rest of the colonic mucosa was normal.

Regarding the management of these varicose veins, the patient benefited from a ligation of the esophageal varices. As for the ectopic sigmoid varix, sclerosis was performed, by diluting 3cc of Aetoxisclerol with 8cc of 9% saline serum. The procedure was uneventful with no immediate complications. Since the intervention and during a 24-month follow-up; the patient did not report any new episode of rectal bleeding.

Discussion

Colonic ectopic varices are an atypical cause of lower digestive bleeding. They are generally due to portal hypertension [2]. A study has estimated that whatever the etiology, ectopic colic varices have an incidence of only 0.07% [3]. Colonoscopy is the best diagnostic tool and also makes it possible to search for more frequent differential diagnosis.

There is no standardized treatment for ectopic varices. The choice of treatment depends first on the etiology of the varix. Most of the data available are in the form of case reports or small series of cases. There is no evidence of the effectiveness of one treatment over another [4]. Pharmacological treatments generally prove to be ineffective (octreotide, propranolol) [5]. Various factors can influence the therapeutic decision such as the location of the varix, the clinical presentation, the expertise and the technical platform available. Different therapeutic modalities can be used in the management of ectopic varices, including endoscopic treatment (ligation, sclerotherapy), interventional radiology techniques (TIPS, BRTO, embolization) and surgical treatment. Ligation and sclerotherapy were successfully used to control the rupture of colonic ectopic varices [6,7]. Nevertheless, elastic ligation seems contraindicated in case of too large varices, in order to avoid secondary ulcers [1], which was the case for our patient. These methods can be used alone or in combination with one another or with other interventional radiology methods. Furthermore, TIPS and radiological embolization are very effective methods. They stop the bleeding by reducing or normalizing the pressurein the portal area. The meta-analysis by Zheng et al showed the superiority of TIPS compared to endoscopic therapies for the prevention of recurrent varices, but it is a technique that worsens encephalopathy [8]. In our context, given the unavailability of TIPS, endoscopic methods remain a simple, effective and feasible treatment for the majority of patients.

Conclusion

There is no standardized treatment for ectopic varices or evidence of the effectiveness of one treatment over another. Their management must be done on a case-by-case basis and the therapeutic choice will depend on the site of the varix, the severity of the bleeding, the expertise and the available technical platform.

References

- Norton ID, Andrews JC, Kamath PS (1998) Management of ectopic varices. Hepatology 28(4): 1154-1158.

- Helmy A, Al Kahtani K, Al Fadda M (2008) Updates in the pathogenesis, diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Hepatol Int 2(3): 322-334.

- Han JH, Jeon WJ, Chae HB, Park SM, Youn SJ, et al. (2006) A case of idiopathic colonic varices: a rare caus of hematochezia misconceived as tumor. World J Gastroenterol 12(16): 2629-2632.

- Akhter NM, Haskal ZJ (2012) Diagnosis and management of ectopic varices. Gastrointest Interv 1(1): 3-10.

- Boursier J, Oberti F, Reaud S, Person B, Maurin A, et al. (2006) Rupture de varice rectale chez un malade avec cirrhose décompensée : efficacité de la ligature endoscopique à propos d’un cas et revue de la litté Gastroenterol Clin Biol 30(5): 783-785.

- Chen WC, Hou MC, Lin HC, Chang FY, Lee SD (2000) An endoscopic injection with N-butyl-2-cyanoacrylate used for colonic variceal bleeding: a case report and review of the literature. American Journal of Gastroenterology 95(2): 540-542.

- Chowdhury AMM, Yue Z, Ying C, Min L (2016) Idiopathic colonic varices: a rare case report. Colorec Cancer 2(2): 1-3.

- Zhang H, Zhang H, Li H, Zhang H, Zheng D, et al. (2017) TIPS versus Endoscopic Therapy for Variceal Rebleeding in Cirrhosis: A Meta-analysis Update. J Huazhong Univ Sci Technol Med Sci 37(4): 475-485.