Advices about Wildlife Rescue

João Carlos Araujo Carreira1*, Cecília Bueno2 and Alba Valeria Machado da Silva3

1Researcher in Public Health, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz /IOC, Brasil

2Veiga de Almeida University, Brasil

3Fundação Oswaldo Cruz /IOC, Brasil

Submission: June 01, 2018;Published: June 11, 2018

*Corresponding author: João Carlos Araujo Carreira, Fundação Oswaldo Cruz /IOC, Av Brasil 4365, Manguinhos, RJ, Brasil, Email: jcacarreira@gmail.com; carreira@ioc.fiocruz.br

How to cite this article: João C A C, Cecília B, Alba V M d S. Advices about Wildlife Rescue. JOJ Case Stud. 2018; 7(3): 555713.10.19080/JOJCS.2018.07.555713.

Keywords: Risk maps; Reintroduction; Wild reservoirs

Editorial

In many countries, the services of wildlife rescue are in general neglected by governmental institutions or represented mostly by philanthropic organizations that certainly make a very important conservation work. Nevertheless, in spite of the efforts for animal health recovering and reintroduction in the right habitat, in several instances there is no care about the possibility that those animals could harbor some parasitic microorganism and introduce them in a new ecosystem.

Introduction

Muir-Torre Syndrome (MTS) is an autosomal dominant disorder characterized by skin neoplasms in association with a visceral malignancy [1]. Visceral malignancies most commonly seen with MTS include colorectal adenocarcinomas and genitourinary malignancies [2], while sebaceous adenomas, epitheliomas and carcinomas constitute the common dermatologic neoplastic conditions usually associated with MTS [2]. Due to its association with germline mutations in the DNA mismatch repair genes MLH1 and MLH2, which occur secondary to DNA microsatellite instability, MTS is considered as a small phenotypic subset of Lynch syndrome [3]. MTS is an exceedingly rare condition, with a high degree of variability in its penetration and expression [4]. Here, we describe a case of a 78-year old man with multiple visceral and dermatologic malignancies who had a prolonged and convoluted course of disease spanning over 40 years.

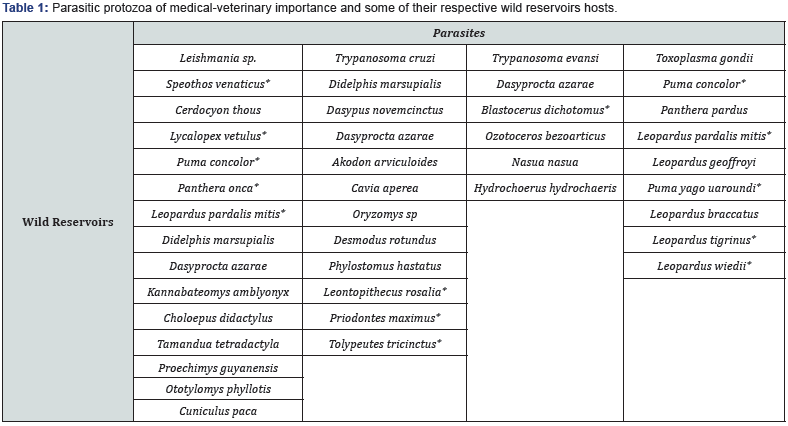

In fact, a great quantity of sylvatic animals, even those included in the list of endangered species, they also may represent important sylvatic reservoirs hosts of parasites that are responsible for animal and human diseases, as can be observed in the Table 1.

One of the major impact component for animal accidents are associated with the roads. The road accident involving the wildlife is a reality throughout the world, actually even during the road construction the impact on the local fauna can be severe [1, 2].

It causes various environmental changes affecting the wildlife behavior, such as modifications in the home range, strategies of predation and the physiological state. In addition, it favors the disordered occupation by the human population and consequently the emergence of epidemic outbreaks, and urbanization spread of parasitic diseases [3]. The importance of saving a sylvatic animal under risk is undeniable nevertheless; it consists in a little bit more complex situation.

In a first view, one could state that the most important in relation of an injured sylvatic animal, principally those under risk of extinction is the recovery of its health and the return to a suitable habitat.

Conversely, some essential points have to be also took in consideration before the reintroduction of the animals, for example:

a) The locations where animal sorting centers will be built they should be carefully evaluated for the risks of exposure to vectors already pre-existing in the area.

b) All newly arrived animals they must be quarantined to avoid transmission of parasites to other animals.

c) It is very important to identify from what specific place the specimen was collected if possible geo-referencing the cases. For performing a posterior anamnesis to facilitate the detection of potential infections.

d) In case injured animals, besides the treatment of the animal health, it should be submitted to a battery of specific tests to the main parasites common in the area, because some animals with subclinical or subpatent infections may signify a potential risk of spreading some parasite to other populations.

e) Once some animal has diagnosed to some parasitic infection and depending on the microorganism identified, it should be isolated for treatment before interaction with the others. In some cases, the infection with a determined parasite can be very dangerous, like Toxoplasma gondii infections in New World primates that are very dangerous, frequently evolving to fatal cases [4].

f) Animals infected with parasites that the treatment would not guaranty a parasitological cure, such as Leishmania, or Trypanosoma cruzi, [5] these animals could not be relocated, to avoid the spreading of parasites for new areas.

These actions are essential to optimize the reintegration of animals into the wild, primarily because they can prevent the spread of infectious diseases by relocating them in areas other than they lived before. Considering that, it could produce a great impact on local fauna and even be responsible by the emergence of a zoonosis in the human population.

Another very important action, constitute of placing microchips in the animals for further elaboration of databases containing the detailed identification and registration of each animal including photography. It would allow the research groups for the development of projects for the collection, characterization and storage of biological material from sylvatic species. In both dead and injured animals, a large number of samples, including tissues, organs and blood, in addition to ecto and endoparasites, are of great importance for the improvement of the local genetic data bank.

With regard to study of the parasites, important information could be obtained, such as: what are the main species and their respective hosts of a specific area, determination of the occurrence of wild cycles, description of new species, establishment of infection rates of hosts, as well as risk maps of infections through geo-referencing and geographic information system studies.

The Geographic Information System (GIS) and Remote Sensing (SR) technologies have been used for the temporal and spatial study of some parasitic diseases of medical and veterinary importance, as well as to evaluate the influence of environmental factors that may be associated with as well as the risk of transmission to humans [6-8].

The implementation of such studies also allows the identification of potential endemic areas related to the places where wild animals are commonly found, thus providing subsidies for the elaboration of control strategies.

Elaboration of risk maps, will make possible the identifying of areas of parasitic diseases where wild animals are commonly found, thus avoiding the spread of these diseases provide support for the development of control strategies.

Finally, a very important achievement consist on the execution environmental education aiming highlighting the awareness and importance of the preservation of sylvatic species, as well as the risk that the contact with these animals can represent as potential reservoirs of diseases.

References

- Glista DJ, Devault TL, Dewoody JA (2008) Vertebrate road mortality predominantly impacts amphibians. Herpetological Conservation and Biology 3(1): 77-87.

- Forman RTT, Alexander LE (1998) Roads and their major ecological effects. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics 29: 207- 231.

- Trombulak SC, Frissell CA (2000) Review of ecological effects of roads on terrestrial and aquatics communities. Conservation Biology 14(1): 18-30.

- Cunningham AA, Buxton D, Thomson KM (1992) An epidemic of toxoplasmosis in a captive colony of squirrel monkeys (Saimiri sciureus). J Comp Pathol 107(2): 207-219.

- Rey L (2001) Chapter 11-19/ Protozoários parasitos do homem. In: Rey L, Parasitologia. (3rd Edn), Guanabara Koogan, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, pp. 179-253.

- Beck LR, Lobitz BM, Wood BL (2000) Remote sensing and human health: new sensors and new opportunities. Emerg Infect Dis 6(3): 217-227.

- Brianti E, Malone JB, Mccarroll JC, Bernardi M, Drigo M, et al. (2004) Minimum Medical GIS Database (MMDb) per l’Europa. Parassitologia 46: 67-70.

- Machado da Silva AV, Magalhães MAFM, Brazil RP, Carreira JCA (2011) Ecological study and risk mapping of leishmaniasis in an endemic area of Brazil based on a geographical information systems approach. Geospatial Health 6(1): 33-40.