Role of Autonomy and Justice in Adolescent Decision Making in Inherited Cancer Syndromes

Kevin Louie1*, Kathleen Murphy1, Rina Meyer1, Devina Prakash2, Ratna B Basak2

1Department of Pediatrics, Stony Brook Children’s, Stony Brook, USA

2Department of Pediatrics Flushing Hospital Medical Center, Cohen Children’s Medical Center and Long Island Jewish Hospital, USA

Submission: May 29, 2018;Published: June 07, 2018

*Corresponding author: Ratna Basak, Department of Pediatrics Flushing Hospital Medical Center, Cohen Children’s Medical Center and Long Island Jewish Hospital, NY, USA, Email: ratnabimalbasak@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Kevin L, Kathleen M, Rina M, Devina P, Ratna B B. Role of Autonomy and Justice in Adolescent Decision Making in Inherited Cancer Syndromes. JOJ Case Stud. 2018; 7(3): 555711. DOI:10.19080/JOJCS.2018.07.555711.

Abstract

Lynch Syndrome is an autosomal dominant disorder caused by a germline mutation of one DNA mismatch repair (MMR) gene or loss of expression of MSH2. Individuals with Lynch Syndrome are at high risk of colorectal cancer, and can develop malignancies of the endometrium, ovary, stomach, small bowel, hepatobiliary system and brain and will continue to develop malignancies throughout their lives [1,2]. This case report examines the complex medical course of an adolescent with Lynch Syndrome and the ethical dilemma between her autonomy and decision-making.

Keywords: Lynch Syndrome; Autonomy; Ethics; Consent; Adolescence

Case

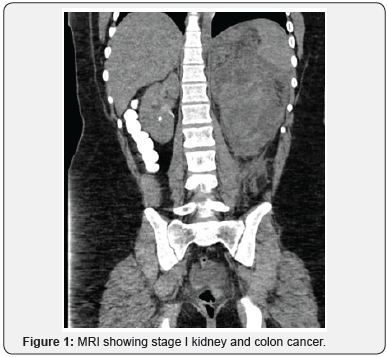

KP is a 14-year-old previously healthy adolescent with family history significant for Lynch Syndrome who presented to the emergency department with flank pain and urinary hesitancy. She was found to have a large mass in the abdomen on imaging, diagnosed as stage I kidney and colon cancer (Figure 1). She underwent left nephrectomy and hemicolectomy with ileostomy. Given family history of Lynch Syndrome, she had gene analysis confirming diagnosis of biallelic Lynch Syndrome.

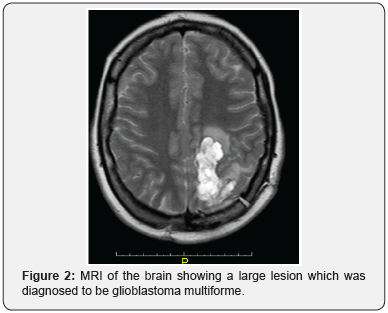

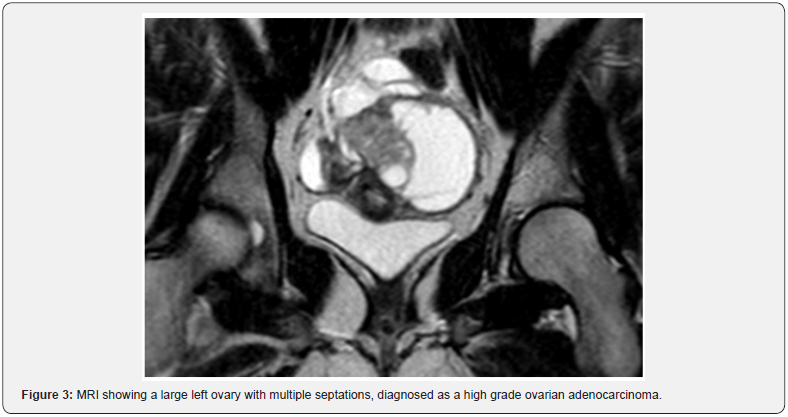

Over the next three years she had multiple new malignancies: Urothelial atypia detected on routine screening cystoscopy, glioblastoma multiforme (Figure 2) detected by brain MRI, endometrial adenocarcinoma after developing menorrhagia, high grade ovarian adenocarcinoma after an episode of lower abdominal pain, and recurrent adenocarcinoma of the colon found on screening colonoscopy. KP has undergone medical and surgical management including intravesical mitomycin, craniotomy with tumor resection, radiation and chemotherapy, and multiple colectomies with revisions (Figure 3).

One of KP’s life goals was to maintain fertility in order to carry out a pregnancy and become a mother. After her diagnosis of endometrial adenocarcinoma, she refused a total abdominal hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy knowing that her chances of developing further malignancies was almost guaranteed. She eventually accepted the procedure after the cancer had metastasized to her ovaries and was optimistic about the possibility of future adoption.

Palliative care had been intimately involved in KP’s care. During consultation, KP was anxious and apprehensive, and avoided all discussions about her diagnosis, prognosis and future treatments with the palliative care team. She had a Palliative performance status of 85-90%. KP has good insight into her medical care and has been fully aware that she is likely to develop new malignancies, a process that may be accelerated by chemotherapy and radiation. She is currently undergoing single agent liposomal doxorubicin for treatment of her ovarian carcinoma.

Discussion

Adolescence is a time of physical and emotional development with demand for autonomy and decision making. Adolescents with acute and chronic illness are particular vulnerable to this developmental period. Post traumatic growth theory suggests that traumatic events like cancer not only cause distress but can spark positive changes including becoming a stronger person and developing new coping skills.

Historically, concealing a bad diagnosis to protect the child from harm was thought to be best practice. Yet, research has shown that most adolescents know when things are not going well, and to withhold honest information about prognosis may lead to mistrust [3-5]. Some adolescents may prefer to be excluded from these difficult conversations and defer all decisional authority to their parents. Consideration should be given to each individual’s cognitive and emotional ability to receive bad news and to participate in decision-making. Clinicians should revisit and gently engage in conversation about the nature of the disease, prognosis, and treatment options if the adolescent desires to be included. These conversations can be difficult, but they facilitate ongoing dialogue of goals and preferences, ultimately alleviating suffering.

It can be distressing to the healthcare team when adolescents decline recommended treatments. This becomes an ethical dilemma when an adolescent and their parents have different treatment opinions. However, studies of adolescents with advanced cancer have shown that they are capable of making and understanding complex medical decisions [5,6]. While adolescents may not be of legal age to consent, it is important to include the patient in these difficult decisions, if they desire, in order to prevent feelings of loss of control. Frequent open communication with all team members can help ensure that the patient understand their thoughts and opinions are vitally important. With a comprehensive team approach, adolescents can help formulate an individualized treatment plan in a shared decision model (Figure 4).

Conclusion

Pediatric cancers are physically, socially and psychologically demanding. This case demonstrates the challenges in dealing with adolescents about poor prognosis, dying, and possible death. These discussions are very difficult, sensitive both in terms of ethical considerations and emotional ramifications. The principles of autonomy, consent, and assent are brought into play here. Shared decision making can help balance developing adolescent autonomy with parental desire to protect their children. Palliative care assists with these difficult discussions to align the patient, parents’, and clinicians’ goals for best outcomes.

References

- Schiffman JD, Geller JI, Mundt E, Means A, Means L, et al. (2013) Update on pediatric cancer predisposition syndromes. Pediatr Blood Cancer 60(8): 1247-1252.

- Wimmer K, Etzler J (2008) Constitutional mismatch repair – deficiency syndrome: have we so far seen only the tip of an iceberg? Hum Genet 124(2): 105-122.

- Rosenberg AR, Orellana L, Ullrich C, Kang T, Geyer JR, et al. (2016) Quality of life in children with advanced cancer: A report from the Pedi QUEST Study. J Pain Symptom Manage 52(2): 243-253.

- Bartholdson C, Lützén K, Blomgren K, Pergert P (2015) Experience of ethical issues when caring for children with cancer. Cancer Nurs 38(2): 125-132.

- Essig S, Steiner C, Kuehni CE, Weber H, Kiss A (2016) Improving communication in adolescent cancer care: A Multiperspective study. Pediatr Blood Cancer 63(8): 1423-1430.

- Straehla JP, Barton KS, Yi-Frazier JP, Wharton C, Baker KS, et al. (2017) The benefits and burdens of cancer: A prospective longitudinal cohort study of adolescents and young adults. J Palliat Med 20(5): 494-501.