COVID-19, Coronavirus-Related Anxiety, and Changes in Women’s Alcohol Use

Susan D Stewart*

Department of Sociology, Iowa State University, USA

Submission: March 02, 2021;Published: March 10, 2021

*Corresponding author: Susan D Stewart, Department of Sociology, Iowa State University, USA

How to cite this article: Susan D S. COVID-19, Coronavirus-Related Anxiety, and Changes in Women’s Alcohol Use. J Gynecol Women’s Health. 2021: 21(2): 556057 10.19080/JGWH.2021.20.556057

Introduction

This study, based on an anonymous on-line survey of 546 women fielded between June 3 and June 30, 2020, examines changes in women’s alcohol use since the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Nearly two-thirds of women reported drinking more since the beginning of the pandemic, including increases in daily drinking, drinking earlier in the day, and binge drinking. Higher scores on coronavirus-related anxiety were associated with significantly greater odds of drinking more. Changes in alcohol consumption varied for different demographics of women. These findings can be considered a first step toward understanding how COVID-19 may be affecting women’s alcohol use.

The coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19) has altered the way we live in fundamental ways: the way we work, interact with others, perform our daily routines, and engage in behaviors related to our health and well-being. Several studies suggest a surge in alcohol use since the outbreak. In a survey of 2,094 U.S. adults conducted in mid-April of 2020, 17% of respondents reported drinking more in the last few weeks compared to 11% who said they drank less [1]. Alcohol sales were 25% higher during the week ending April 4, 2020 compared to that same week in 2019, and liquor stores in large cities are reporting substantial increases in sales [1,2]. Nationally, estimates indicate a 55% increase in retail alcohol sales between the second and third week of March 2020 [3]. At the same time, economic constraints as a result of the pandemic mean families have less discretionary income, and bar and restaurant closures and cancellation of sporting events provide fewer opportunities to drink outside the home.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has suggested that people are using alcohol to cope with stress brought on by the pandemic [4]. In mid-April 2020, life satisfaction among Americans reached a 12-year low [5]. Potential stressors include unemployment, lost wages, inability to pay bills, and overall economic uncertainty [6]. People who have retained their jobs have had to adjust to working from home, and/or new social distancing and cleanliness standards at the workplace. Other contributing factors thought to be related to increased alcohol use are loneliness and social isolation, inability to exercise or take part in hobbies, and changes in work responsibilities. Parents, and women, are often juggling work and childcare in addition to caring for family members at high risk of COVID-19, with no clear idea of how long the situation will go on [7]. Such chronic ambiguity with respect to roles, relationships, and responsibilities is especially damaging to people’s emotional and physical health [8]. A study of Australian women found drinking intentions and/or behavior were related to “having a stressful week” and because it “makes me feel relaxed” [9].

Women also make up half the American workforce and are disproportionately employed in occupations deemed essential, and it is widely recognized that essential workers are under an extreme amount of stress [10,11]. Stress, and work-family spillover, is associated with greater alcohol consumption among women [12,13]. Female workers in occupations not deemed essential are more likely than men to have experienced massive layoffs as a result of the pandemic [14]. Unemployment is associated with greater alcohol use and abuse [15-17]. Moreover, a study of 775 U.S. adults in mid-March of 2020 found anxiety specifically related to COVID-19 to be associated with greater alcohol use [18], and a study of women and men in Spain found that women experienced higher levels of depression, anxiety, PTSD, loneliness, and less spiritual well-being than did men during the COVID-19 lockdown [19].

Alcohol use had already been on the rise before COVID-19. In 2019, the average number of drinks consumed by Americans in the past week was 4.0, compared to 2.8 in 1996, a 43% increase [20]. Meanwhile, so-called “deaths of despair,” deaths due to alcohol, suicide, or drugs, are responsible for increased death rates and the notable 2015 reversion in U.S. life expectancy [21,22]. Alcohol-related deaths kill roughly 88,000 Americans each year and are the third leading preventable cause of death [23,24]. Alcohol increases the risk of cancer, liver disease, dementia, depression, and suicide and the Global Burden of Disease suggests that no amount of alcohol is healthy [25-29]. Researchers are anticipating an increase in deaths of despair as a result of the coronavirus pandemic [30].

Although women drink less alcohol than do men [31-33], numerous studies show a convergence of women’s and men’s alcohol use in terms of prevalence, amount, and frequency, as well as alcohol-related problems and harms [34-37]. This convergence is being driven mainly by increases in alcohol use among women as opposed to declines among men [36]. Analysis of the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions indicated that women experienced a 16% increase in past year alcohol use, a 58% increase in high-risk drinking, and an 84% increase in alcohol use disorder between 2002 and 2013 [37]. A meta-analysis of six U.S. surveys indicated a 10% increase in prevalence of alcohol use and 23% increase in binge drinking among women between 2000 and 2016, with no corresponding increase for men [38].

Women are more susceptible to alcohol-related health conditions than are men, as well as infertility, reproductive problems, and breast cancer [39-41]. Women have experienced the same plateau in life expectancy as men partly a result of increases in alcohol-related deaths and liver disease [42-44]. An analysis of U.S. death certificates filed between 1999 and 2017 showed an 85% increase in deaths due to alcohol among women compared to an increase of only 35% for men [24].

There have been recent calls for research on the effect of COVID-19 on alcohol consumption, harms, and policies [45,46]. The use and overuse of alcohol has increased substantially among women with negative effects on their health and emotional wellbeing. As the main caretakers of children, aging parents, and extended family members, women’s use of alcohol can reverberate across the family system and between generations. One in ten children live with a parent who has an Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD); 1.4 million of those live with a single parent, most often with their mothers [47]. Alcohol is associated with child abuse, neglect, and interpersonal violence [48,49]. There is growing alarm as to how COVID-19 is affecting women with children, who are widely viewed as being under particularly stressful conditions since the pandemic. Jokes and memes about mothers’ increased reliance on alcohol to cope with work, childcare, and managing their children’s on-line education, have exploded on social media since the pandemic.

A developmental perspective on alcohol use stresses that “variability in drinking patterns is not constant across the lifespan, and that pressures to drink-or not to drink-are concentrated at certain stages in the course of a person’s life” [50]. Indeed, a woman’s use of alcohol over her lifetime or her drinking trajectory, is particularly sensitive to life course transitions. Some transitions are protective against alcohol use, including steady employment [51,52], marriage [53-57], and parenthood [54,58-60]. Others, such as attending college and divorce, are associated with the greater use of alcohol (Chilcoat & Breslau 1996; [60]. Drinking tends to decline with age [55,61,62], although more recent studies suggest increase drinking among people in midlife and older, especially among women [37,38,63]. White, college-educated, and higher income women experienced the greatest increase in alcohol consumption in recent years and drink significantly more than do other women [34,64-66]. Religiosity and organized religion are inversely related to alcohol use and alcohol-related problems [67,68].

The aim of this study is to assess changes in women’s alcohol consumption since COVID-19, and to understand the role of coronavirus-related anxiety, and women’s social and demographic characteristics. There is only one other similar study available currently. In a national study, Australian researchers found an increase in self-reported alcohol consumption among women and men during the pandemic (May 2020) than 2 to 3 years prior, but that the increase was substantially higher among women, and that having a child caring role was a strong predictor of an increase in alcohol consumption [69]. They did not examine the role of anxiety related to COVID-19.

Given large variation in rates of positive cases of COVID-19 and COVID-19-related hospitalizations and deaths across U.S. states, this study explores regional differences in these patterns. The survey contains a series alcohol use questions adapted from the National Institutes on Alcoholism and Alcohol Abuse adapted to capture drinking pre- and post-COVID-19, including frequency, number of drinks, and frequency of binge drinking [70], as well as the time-of-day alcohol is consumed and type of drink, and contains a broad range of sociodemographic variables. A coronavirus anxiety scale was designed by the researcher.

Materials and Methods

The study is based on an anonymous on-line Qualtrics survey of 546 women age 25 and older who reported drinking alcohol at least occasionally. Women under the age of 25 were excluded because they demonstrate a temporary upswing in drinking and binge drinking. Participants were recruited primarily through social media (Facebook, Twitter, etc.), but also by email, listserves, and newsletters. The survey was fielded between June 3 and June 30, 2020. Participants were directed to a website containing a consent form and a Qualtrics survey which they could access through their smartphones, computer, or other electronic device. Participants were encouraged to share the link to the study with others in their social network.

The main objective of the survey was to measure women’s alcohol consumption pre- and post-COVID-19. Respondents were first asked about their current level of alcohol consumption. Since COVID-19 and social distancing measures began in your area, about how often do you have any kind of drink containing alcohol? By a drink, we mean half an ounce of absolute alcohol (e.g. a 12-ounce can or glass of beer or cooler, a 5-ounce glass of wine, or a drink containing 1 shot of liquor)? Responses ranged from 1 (every day) to 10 (less than a few times a year). About how many alcoholic drinks would you say you have on a typical day when you drink alcohol? Responses ranged from 1 (one drink) to 7 (12 or more drinks). Respondents were then asked about their frequency of binge drinking. About how often would you say you have 4 or more drinks containing any kind of alcohol in within a two-hour period? That would be the equivalent of at least 4 - 12-ounce cans or bottles of beer, 4 - 5-ounce glasses of wine, 4 drinks each containing one shot of liquor or spirits. Responses ranged from 1 (never) to 9 (every day). Respondents were also asked about their typical pattern of alcohol consumption: On days you drink, when do you usually have your first drink? Potential responses included before lunchtime, around lunchtime, mid-afternoon, before dinner, with dinner, and after dinner or evening. Then, On days you drink, what type of drink do you have most often? Respondents could select from beer, wine, cocktails or mixed drinks, liquor or spirits (straight), and other. Finally, the women were asked, on days you drink, do you tend to switch from one kind of drink to another? Response categories were yes, I tend to switch from drinks with less alcohol to drinks with more, such as from beer to wine; yes, I tend to switch from drinks with more alcohol to drinks with less, such as from wine to beer; and, no, I tend to drink the same kind of drink all day.

Respondents were then asked about their pre-COVID-19 level of drinking. Before COVID-19 and social distancing measures began in your area, would you say you drank quite a bit less than I do now, somewhat less than I do now, the same amount as I do now, somewhat more than I do now, or quite a bit more than I do now? Respondents who reported drinking “the same amount” were asked, if you drank the same amount as now, were there ever periods of time during COVID-19 and social distancing measures began in your area when you drank more or less alcohol than you did? Potential responses were yes, there were times when I drank more; yes, there were times when I drank less; and, no, I’ve been drinking about the same amount throughout the pandemic. Respondents who reported a change in their alcohol consumption answered the same series of alcohol consumption questions in relation to before COVID-19.

The Coronavirus Anxiety Scale, designed for this study, contains 9 items designed to capture anxiety about COVID-19 (Stewart, 2020). Respondents were asked, since COVID-19 and social distancing measures began in your area, on a scale from 1 (never) to 5 (often), how often have you thought about the following: (a) me or a family member contracting the coronavirus, (b) me or a family member getting seriously ill or dying from the coronavirus, (c) others getting sick or dying from the coronavirus, (d) my personal finances and providing for my family, (e) the economy in general, (f) not being able to see friends and family, (g) the mental health and emotional well-being of friends and family, (h) my mental health and emotional well-being, and (i) the future of the country. The scale has a high level of reliability with a Cronbach’s alpha of .83. The women in the sample exhibited a moderate to high level of anxiety with an average level of 3.6.

Respondents provided information on their social and economic characteristics. Age was recorded in years and is grouped in terms of the following: 25 to 29, 30 to 39, 40 to 49, 50 to 59, and 60 and older. Racial and ethnic identity is coded as White, Black/African American, Hispanic, Asian/Asian Indian, and other or more than one race. Due to small cell sizes, the latter categories were coded as non-White. Relationship status was coded as single, cohabiting, and married. Educational attainment is a three-category measure: less than a bachelor’s degree, bachelor’s degree, to graduate or professional degree. Respondents were asked whether and how their employment situation has been affected by the pandemic: yes, I lost my job or was furloughed; yes, I work fewer hours; yes, I work more hours; yes, I work from home some or all of the time; and, no, my work life has stayed the same. Respondent’s reporting having lost their job, having been furloughed, or worked fewer or more hours were combined in the multivariate analysis. Whether or not respondents had children was coded as a dichotomous variable (yes, no). Categories of religious affiliation included Catholic, Protestant, Jewish, Muslim, other religion, and no affiliation. Respondents recorded the region where they live: Northeast, Midwest, South, or West. Yearly gross household income in 2019 ranged from less than $25,000, $25,000 to $49,999, $50,000 to $74,999, $75,000 to $99,999, $100,000 to $149,000, $150,000 to $199,999, and $200,000 or more. Respondents with household incomes less than $75,000 were combined. The distribution of these variables can be found in Table 1.

Result

Table 2 describes women’s perceptions of changes in their alcohol consumption since COVID-19. Results in Panel 1 indicate that women’s alcohol consumption has increased since the beginning of the pandemic. Nearly two-thirds (64%) of women reported drinking quite a bit less (22%) or somewhat less (43%) before the pandemic than after. Only 13% of women reported drinking somewhat more or quite a bit more before COVID-19, and 23% reported drinking the same amount. Among those who reported drinking the same amount, 29% reported there were times since COVID-19 when they drank more, and 9.4% said there were times when they drank less. Panel 3 combines information from these two questions. Compared to pre-COVID-19, 15.2% of women reported ever drinking quite a bit less or somewhat less, 70% of women reported ever drinking quite a bit more or somewhat more, and 14.5% of women say they consistently drank the same amount pre- and post-COVID-19.

Table 3 examines changes in women’s drinking in greater detail. First, there was a three-fold increase in daily drinking, from 4.6% pre-COVID-19 to 15.6% post-COVID-19. The volume of drinks consumed remained relatively consistent across time, although there was a slight decline in the percent of women who drank just one drink, from 32.4% to 26.9%. Women’s frequency of binge drinking (drinking 4 or more drinks within a two-hour period) showed an interesting pattern with an increase in never (from 37.0% to 42.5%) and an increase in weekly (15.4% to 23.1%). There was also a shift in drinking from later in the day to earlier in the day. Pre-COVID-19, 4.4% of women reported having their first drink by mid-afternoon compared to 16.1% post-COVID-19. The type of alcohol consumed remained relatively consistent, with a slight increase in drinking cocktails, liquor, and beverages other than beer and wine. At both time points, most women drank beverages with the same amount of alcohol throughout the day (90.0% and 88.1%) as opposed to switching from one kind of drink to another.

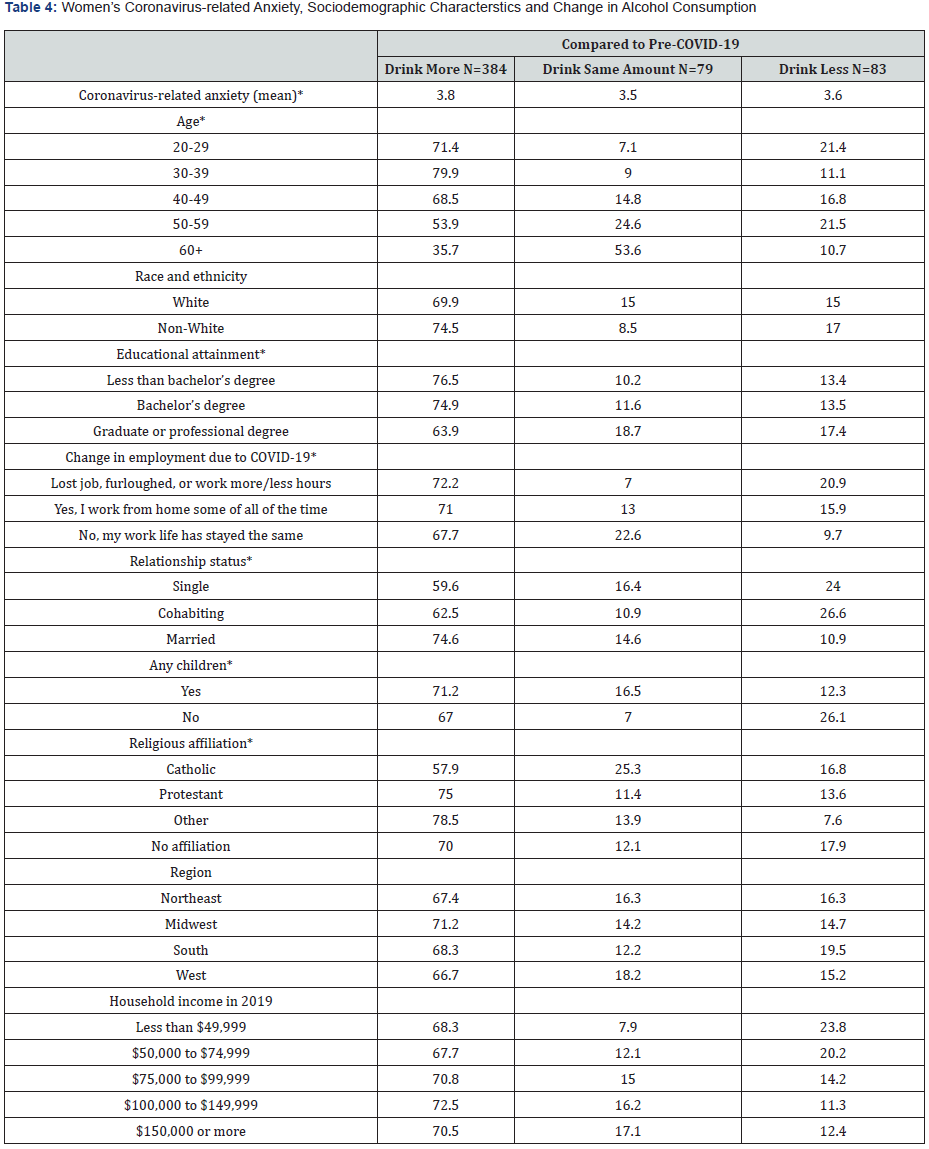

Table 4 describes the bivariate relationship between coronavirus-related anxiety, women’s sociodemographic characteristics, and changes in alcohol consumption since COVID-19. Significant differences across categories are noted. First, women who reported drinking more after the pandemic reported a significantly higher level of COVID-19-related anxiety (3.8) than did women who reported drinking the same amount (3.5) or less (3.6), although the difference in magnitude between groups is small. A higher percentage of younger women than older women reported drinking more since the pandemic. Women age 60 and older demonstrated the most stability in drinking; 53.6% reported drinking the same amount before and after COVID-19. A slightly higher percentage of non-White women reported drinking more. A significantly lower percentage of women with graduate or professional degrees reported drinking more (63.9%) compared to women with a bachelor’s degree (74.9%) or less than a bachelor’s degree (76.5%). Changes in employment were associated with changes in alcohol consumption. Women who lost their job, were furloughed, or who worked hours than before the pandemic exhibited significantly less stable alcohol consumption before and after COVID-19 than did women whose work life remained the same. For example, only 7.0% in those categories drank the same amount at both time points compared to 23% of women whose work life did not change after COVID-19. Relationship status, particularly marriage, was also important. Three-fourths of married women (74.6%) reported drinking more since the pandemic, compared to 62.5% of cohabiting women and 59.6% of single women. Less than half the percentage of married women reported drinking less (10.9%) than cohabiting or single women (26.6% and 24.0%, respectfully). A significantly lower percentage of Catholic women reported drinking more (57.9%) or the same amount (25.3%) since the pandemic than women of other religious affiliations. There were no significant regional or income differences in changes in women’s alcohol consumption.

Note: Cells may not total to 100% due to rounding.

Note: Cells may not total to 100% due to rounding. *Significant differences between groups at p < 05.

Table 5 provides the results of a logistic regression, in the form of odds ratios, that assesses the independent effects of women’s coronavirus-related anxiety and their sociodemographic characteristics on changes in women’s alcohol consumption preand post-COVID-19. A test of the proportional odds assumption suggests that binary logistic regression (more versus same/ less) is preferred over a three-category ordered or multinomial logit model [71]. Model 1 indicates that women with higher coronavirus-related anxiety have higher odds of drinking more post-COVID-19 than pre-COVID-19. Every one-unit increase in anxiety is associated with 32.6% higher odds of drinking more after the pandemic as opposed to the same amount or less. Older women, namely women age 50 to 59 and sixty and older, have significantly lower odds (55.0% and 78.0%, respectively) of increasing their alcohol consumption compared to women in their twenties. Compared to women with less than a bachelor’s degree, women with advanced degrees have 57.5% lower odds of increasing their alcohol consumption than women with less than a bachelor’s degree and 48.5% lower odds compared to women with a bachelor’s degree (data not shown). Catholic women have 62.4% lower odds of increased alcohol use compared to Protestant women. On the other hand, married women are over twice as likely to have increased their alcohol consumption compared to single women and cohabiting women (data not shown). Women’s characteristics not associated with changes in alcohol use include race and ethnicity, changes in employment situation, region, and income. Additional analysis did not find a statistically significant relationship between employment status (full-time, part-time, and not employed), religious service attendance, and changes in women’s alcohol use (results not shown).

*p < 05; **p<.01; ***p < .001.

At baseline, having children was not associated with changes in drinking since the pandemic. However, the effect of children may be dependent upon women’s relationships status. For example, the presumed stress of having a child could be compounded by traditional role responsibilities associated with marriage. Model 2 includes an interaction between relationship status and any children. However, result indicate having children reduces the odds of increased alcohol consumption among married women by 69.3%. Children are not associated with changes in alcohol consumption among cohabiting or single women.

Discussion

Although women drink less alcohol than do men [31,32], numerous studies show that women’s use of alcohol is catching up to that of men’s in terms of prevalence, amount, and frequency, as well as alcohol-related illnesses and deaths [35]. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services estimates there are 5.3 million women in the U.S. who are heavy drinkers or who “drink in a way that threatens their health, safety, and general wellbeing” (2018, p. 6). Alcohol-related cirrhosis increased 50% in women between 2009 and 2015 [43]. In an analysis of data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC), nearly a third of women surveyed (23%) reported previous levels of alcohol use consistent with an alcohol use disorder, with 10% showing symptoms of an AUD in the past 12 months [32].

The results of this survey are consistent with studies suggesting a rise in alcohol use since COVID-19 (e.g., [69] and that anxiety about the pandemic playx a role, supporting anecdotal evidence and widespread media reports. Results regarding women’s sociodemographic characteristics are for the most part in line with previous research. A lower proportion of older women than younger women increased their alcohol consumption. Although religiosity and organized religion are generally associated with less alcohol use and alcohol-related problems [67,68], results indicate lower odds of increased drinking among only Catholic women. Although women with advanced degrees had lower odds of drinking more since the pandemic, they also had a higher level of alcohol consumption pre-COVID-19 (43% drank at least three to four times a week versus 28% of women with a bachelor’s degree or less), consistent with prior work showing greater alcohol use among more educated women [55,65,72]. As noted above, race and ethnicity, changes in employment situation, employment status, region, and income, religious service attendance, were not associated with changes in women’s alcohol use, in contrast to previous research indicating these are important variables to consider. However, previous research assessed these relationships with respect to current levels of drinking as opposed to this study which examines change over time.

The positive effect of marriage on increased alcohol consumption is interesting given that marriage has long been considered a protective factor against substance use [37,53,54]. However, married women have been found to have higher rates of alcohol consumption than unpartnered women, at least among Whites [65]. Reczek et al. [57] examined the marital biographies of men and women from the Health and Retirement Study and found that marriage and remarriage reduced men’s heavy alcohol use (3+ drinks at least one day each week) but increased women’s and that divorce increased men’s drinking but reduced women’s. This work suggests that married women may be under greater stress since the pandemic, perhaps a result of having a husband at home more of the time. Gender roles and gender role attitudes are more traditional among married women than among cohabiting and single women, and married women may feel particularly responsible for “keeping things together” on the home front, even if working full time. The results may also be related to increased drinking among husbands since the pandemic, as women’s drinking is highly sensitive to that of their spouse [57]. The effect of the pandemic on men’s alcohol use is currently unknown, but financial strain and increased stress post-COVID-19 is certainly not exclusive to women. Results are also consistent with research showing lower levels of alcohol consumption among mothers, despite anecdotal evidence to the contrary [53, 54] Hayden et al. [58].

It is important to reemphasize that these results are not representative of the national population and are based on the experiences of a largely White, college-educated sample of women recruited through social media. Nevertheless, this sample reflects women who have the highest levels of alcohol consumption relative to other women and who have experienced the greatest increase in alcohol use in recent years [34,64, 66]. Women’s reports are retrospective, and respondents may not accurately recall their behaviors and feelings before the pandemic, although the survey was constructed to minimize over-inflation of alcohol use since the pandemic by asking about their current usage prior to asking about previous levels. It is hoped that, in the absence of national studies, this study contributes to our understanding of changes in women’s alcohol use as it relates to COVID-19. Studies conducted at the national level are needed, as are longitudinal assessments of women’s alcohol use over time, and especially studies focusing on women of color, and less educated and lower income women.

Women’s increased alcohol use since the pandemic is especially troubling given their level of alcohol use had already been on the increase. There are already many barriers for women getting treatment for alcohol overuse that prolong women’s alcohol dependency and health risks. Guilt, shame, being perceived as a “bad mom,” lack of childcare, the cost of treatment, and familial opposition, the lack of gender-specific treatment, physicians being slow to recognize AUDs in women, and for single mothers, the potential loss of custody [73-76]. Since the pandemic, many women have lost access to mental health services, substance use resources, and have been cut off from family and friends [30]. These findings suggest the importance of continued study of how COVID-19 is impacting women’s alcohol use, factors underlying increased consumption, and the effect of drinking on women’s social and emotional health and on the well-being of their families [77,78].

Acknowledgement

I thank Renea Miller and Arielle True-Funk for their excellent contributions to the design and construction of the survey.

Declaration of Interest Statement

There has been no financial interest or benefit that has arisen from this research.

Biographical Note

Susan D. Stewart is a Professor of Sociology at Iowa State University. She received her Doctorate in Sociology from Bowling Green State University. Dr. Stewart is a family demographer whose research focuses on gender, parenting, family diversity, and children and adults’ physical, social, and emotional health. Stewart is the author or co-author of several books including, Multicultural Stepfamilies; Brave New Stepfamilies: Diverse Paths Toward Stepfamily Living; Marriages, Families, and Relationships; and Co-Sleeping: Parents, Children and Musical Beds. Her research has been supported by grants from the NICHD, USDA, Joint Center for Poverty Research, and the Annie E. Casey Foundation. She has conducted research on a diverse array of topics, including divorce, stepfamilies, women’s alcohol use, family stress, childhood obesity, adoption, and women’s financial literacy.

References

- Ianzito C (2020) Alcohol use on the rise during the pandemic.

- Giangreco L (2020) At D.C.’s liquor stores, sales have doubled and a whole lot of Everclear is flying off the shelves.

- Nielson (2020) Rebalancing the ‘COVID-19 effect’ on alcohol sales.

- Centers for Disease Control (2020) Alcohol and substance use.

- Witters D, Harter J (2020) In US, life rating plummet to 12-year low.

- Goeij DMC, Suhrcke M, Toffolutti V, Mheen VDD, Schoenmakers TM, et al. (2015) How economic crises affect alcohol consumption and alcohol-related health problems: a realist systematic review. Soc Sci Med 131: 131-146.

- Cluver L, Lachman JM, Sherr L, Wessels I, Krug E, et al. (2020) Parenting in a time of COVID-19. Lancet 395(10231): e64.

- Boss P, Bryant CM, Mancini JA (2016) Alcohol and depression. Addiction. Sage Publications, Newbury Park, CA.

- Haydon HM, Obst PL, Lewis I (2016) Beliefs underlying women’s intentions to consume alcohol. BMC Women's Health 16: 36.

- Robertson C, Gebeloff R (2020) How millions of women because the most essential workers in America.

- US Department of Labor (2020) 12 Stats about working women.

- Frone MR (2016) Work stress and alcohol use: developing and testing a biphasic self-medication model. Work & Stress 30(4): 374-394.

- Grzywacz JG, Marks NF (2000) Family, work, work‐family spillover, and problem drinking during midlife. Journal of Marriage and Family 62(2): 336-348.

- Kochhar R (2020) Unemployment rose higher in three months of COVID-19 than it did in two years of the Great Recession.

- Catalano R, Dooley D, Wilson G, Hough R (1993) Job loss and alcohol abuse: a test using data from the Epidemiologic Catchment Area project. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 34(3): 215-225.

- Compton WM, Gfroerer J, Conway KP, Finger MS (2014) Unemployment and substance outcomes in the United States 2002-2010. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 142: 350-353.

- Henkel D (2011) Unemployment and substance use: a review of the literature (1990-2010). Current Drug Abuse Reviews 4(1): 4-27.

- Lee SA (2020) Coronavirus Anxiety Scale: A brief mental health screener for COVID-19 related anxiety. Death Stud 44(7): 393-401.

- Ausín B, González-Sanguino C, Castellanos MÁ, Muñoz M (2020) Gender-related differences in the psychological impact of confinement as a consequence of COVID-19 in Spain. Journal of Gender Studies 33(1): 1-10.

- Gallup (2019) Alcohol and drinking. Gallup historical trends.

- Acciai F, Firebaugh G (2017) Why did life expectancy decline in the United States in 2015? A gender-specific analysis. Soc Sci Med 190: 174-180.

- Case A, Deaton A (2015) Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 112(49): 15078-15083.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2017) Alcohol facts and statistics.

- White AM, Castle IJP, Hingson RW, Powell PA (2020) Using death certificates to explore changes in alcohol‐related mortality in the United States, 1999 to 2017. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 44(1): 178-187.

- Boden JM, Fergusson DM (2011) Alcohol and depression. Addiction 106: 906-914.

- Connor J (2017) Alcohol consumption as a cause of cancer. Addiction 112(2): 222-228.

- Griswold MG, Fullman N, Hawley C, Arian N, Zimsen SR, et al. (2018) Alcohol use and burden for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. The Lancet 392: 1015-1035.

- Ridley NJ, Draper B, Withall A (2013) Alcohol-related dementia: an update of the evidence. Alzheimers Res Ther 5(1): 3.

- Tapper EB, Parikh ND (2018) Mortality due to cirrhosis and liver cancer in the United States, 1999-2016: Observational study. Bmj 362: k2817.

- Petterson S, Westfall JM, Miller BF (2020) Projected deaths of despair from COVID-19.

- Esser MB, Hedden SL, Kanny D, Brewer RD, Gfroerer JC, et al. (2014) Prevalence of alcohol dependence among US adult drinkers, 2009-2011. Prev Chronic Dis 11: E206.

- Grant BF, Goldstein RB, Saha TD, Chou SP, Jung J, et al. (2015) Epidemiology of DSM-5 alcohol use disorder: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions III. JAMA Psychiatry 72: 757-766.

- Wilsnack RW, Vogeltanz ND, Wilsnack SC, Harris TR (2000) Gender differences in alcohol consumption and adverse drinking consequences: Cross‐cultural patterns. Addiction 95(2): 251-265.

- Jones JM (2015) Drinking highest among educated upper-income Americans.

- Slade T, Chapman C, Swift W, Keyes K, Tonks Z, et al. (2016) Birth cohort trends in the global epidemiology of alcohol use and alcohol-related harms in men and women: systematic review and metaregression. BMJ Open 6(10): e011827.

- White A, Castle IJP, Chen CM, Shirley M, Roach D, et al. (2015) Converging patterns of alcohol use and related outcomes among females and males in the United States, 2002 to 2012. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 39(9): 1712-1726.

- Grant BF, Chou SP, Saha TD, Pickering RP, Kerridge BT, et al. (2017) Prevalence of 12-month alcohol use, high-risk drinking, and DSM-IV alcohol use disorder in the United States, 2001-2002 to 2012-2013: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions. JAMA Psychiatry 74(9): 911-923.

- Grucza RA, Sher KJ, Kerr WC, Krauss MJ, Lui CK, et al. (2018) Trends in adult alcohol use and binge drinking in the early 21st‐century United States: a meta‐analysis of 6 National Survey Series. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 42(10): 1939-1950.

- Institute of Alcohol Studies (2017) The effects of alcohol on women.

- Milic J, Glisic M, Voortman T, Borba LP, Asllanaj E, et al. (2018) Menopause, ageing, and alcohol use disorders in women. Maturitas 111: 100-109.

- Petri AL, Tjønneland A, Gamborg M, Johansen D, Høidrup S, et al. (2004) Alcohol intake, type of beverage, and risk of breast cancer in pre‐and postmenopausal women. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 28(7): 1084-1090.

- Murphy SL, Xu J, Kochanek KD, Curtin SC, Arias E, et al. (2017) Deaths: final data for 2015. National Vital Statistics Repository 66(6): 1-75.

- Mellinger JL, Shedden K, Winder GS, Tapper E, Adams M, et al. (2018) The high burden of alcoholic cirrhosis in privately insured persons in the United States. Hepatology 68(3): 872-882.

- Tinker B (2017) US Life Expectancy Drops for Second Year in a Row.

- Mazza M, Marano G, Lai C, Janiri L, Sani G, et al. (2020) Danger in danger: interpersonal violence during COVID-19 quarantine. Psychiatry Res 289: 113046.

- Monteiro MG, Rehm J, Duennbier M (2020) Alcohol policy and coronavirus: An open research agenda. J Stud Alcohol Drugs 81(3): 297-299.

- Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality (2012) More than 7 million children live with a parent with alcohol problems.

- Caetano R, Schafer J, Cunradi CB (2017) Alcohol-related intimate partner violence among white, black, and Hispanic couples in the United States. Alcohol Research & Health 25(1): 58-65.

- Neger EN, Prinz RJ (2015) Interventions to address parenting and parental substance abuse: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Clin Psychol Rev 39: 71-82.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse, & Alcoholism (US) (2000) Special Report to the US Congress on Alcohol and Health from the Secretary of Health and Human Services, 10.

- Johnson FW, Gruenewald PJ, Treno AJ, Taff GA (1998) Drinking over the life course within gender and ethnic groups: a hyperparametric analysis. J Stud Alcohol 59(5): 568-580.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2020b) Recommended alcohol questions.

- Caetano R, Ramisetty‐Mikler S, Floyd LR, McGrath C (2006) The epidemiology of drinking among women of child‐bearing age. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 30(6): 1023-1030.

- Cho YI, Crittenden KS (2006) The impact of adult roles on drinking among women in the United States. Subst Use Misuse 41(1): 17-34.

- Kerr WC, Greenfield TK, Bond J, Ye Y, Rehm J, et al. (2009) Age-period-cohort modelling of alcohol volume and heavy drinking days in the US National Alcohol Surveys: divergence in younger and older adult trends. Addiction 104(1): 27-37.

- Miller-Tutzauer C, Leonard KE, Windle M (1991) Marriage and alcohol use: a longitudinal study of “maturing out.” J Stud Alcohol 52(5): 434-440.

- Reczek C, Pudrovska T, Carr D, Thomeer MB, Umberson D, et al. (2016) Marital histories and heavy alcohol use among older adults. J Health Soc Behav 57(1): 77-96.

- Laborde ND, Mair C (2012) Alcohol use patterns among postpartum women. Matern Child Health J 16(9): 1810-1819.

- Mudar P, Kearns JN, Leonard KE (2002) The transition to marriage and changes in alcohol involvement among black couples and white couples. J Stud Alcohol 63(5): 568-576.

- Stone AL, Becker LG, Huber AM, Catalano RF (2012) Review of risk and protective factors of substance use and problem use in emerging adulthood. Addict Behav 37(7): 747-775.

- Keyes KM, Miech R (2013) Age, period, and cohort effects in heavy episodic drinking in the US from 1985 to 2009. Drug and Alcohol Dependence 132(1-2): 140-148.

- Wilsnack RW, Kristjanson AF, Wilsnack SC, Crosby RD (2006) Are US women drinking less (or more)? Historical and aging trends, 1981-2001. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 67(3): 341-348.

- Breslow RA, Castle IJP, Chen CM, Graubard BI (2017) Trends in alcohol consumption among older Americans: National Health Interview Surveys, 1997 to 2014. Alcohol Clin Exp Res 41(5): 976-986.

- Keating D (2016) Nine charts that show how white women are drinking themselves to death.

- Stewart SD, Jones-Johnson G, Dorius C (2019) Women and Alcohol Use over the Lifecourse: An Intersectional Approach. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association, New York, USA.

- Woolf SH, Chapman DA, Buchanich JM, Bobby KJ, Zimmerman EB, et al. (2018) Changes in midlife death rates across racial and ethnic groups in the United States: systematic analysis of vital statistics. Bmj 362: k3096.

- Edlund MJ, Harris KM, Koenig HG, Han X, Sullivan G, et al. (2010) Religiosity and decreased risk of substance use disorders: is the effect mediated by social support or mental health status? Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 45(8): 827-836.

- Holt CL, Roth DL, Huang J, Clark EM (2015) Gender differences in the roles of religion and locus of control on alcohol use and smoking among African Americans. Journal of Studies on Alcohol and Drugs 76(3): 482-492.

- Biddle N, Edwards B, Gray M, Sollis K (2020) Alcohol consumption during the COVID-19 period: May 2020. COVID-19 Briefing Paper.

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (2020a) Alcohol use disorder: A comparison between DSM-IV and DSM-5.

- Brant R (1990) Assessing proportionality in the proportional odds model for ordinal logistic regression. Biometrics 46(4): 1171-1178.

- Jones JM (2006) US drinkers consuming alcohol more regularly.

- Beckman LJ (1994) Treatment needs for women with alcohol problems. Alcohol Health Res World 18(3): 206-211.

- Finkelstein N (1994) Treatment issues for alcohol-and drug-dependent pregnant and parenting women.

Health Soc Work 19(1): 7-15. - Kelly JF, Hoeppner BB (2013) Does Alcoholics Anonymous work differently for men and women? A moderated multiple-mediation analysis in a large clinical sample. Drug Alcohol Depend 130(1-3): 186-193.

- Walde VDH, Urgenson FT, Weltz SH, Hanna FJ (2002) Women and alcoholism: A biopsychosocial perspective and treatment approaches. Journal of Counseling & Development 80(2): 145-153.

- Central H (1965) The pattern of human concerns. Rutgers University Press, New Brunswick, NJ.

- US Department of Health and Human Services (2018) Alcohol: A women’s health issue.