Body Image Disorder in Women Treated for Uterine Cancer

Ghorbel Asma*, Yousfi Amani, Abidi Rim, Yahyaoui Safia, Zarraa Semia, Mahjoubi Khalil, Gargouri Walid, Belaid Asma and Nasr Chiraz

Department of Radiotherapy, Institute Salah Azaïz, Tunisia

Submission: December 02, 2020;Published: December 07, 2020

*Corresponding author: Asma Ghorbel, Department of Radiotherapy, Institute Salah Azaïz, Tunisia

How to cite this article: Ghorbel A, Yousfi A, Abidi R, Yahyaoui S, Zarraa S, et al. Body Image Disorder in Women Treated for Uterine Cancer. J Gynecol Women’s Health. 2020: 20(3): 556036. DOI: 10.19080/JGWH.2020.19.556036

Abstract

Introduction: When it affects the uterus, a hidden organ but associated with a very intense fantasy, cancer can upset a woman’s body image and call into question her feminine identity and her relationship as a couple.

Objectives: The aim of this work was to research the prevalence of the problem of the image of the body in women followed for uterine cancer as well as the factors associated with it.

Patients: We carried out a descriptive cross-sectional study of one hundred patients treated for uterine cancer. We passed the BIS scale to these patients.

Result: We noted that 40% of patients had body image disturbances. The mean BIS score was 12.03 with extremes ranging from 0 to 30 with a standard deviation of 7,88. In univariate analysis, the absence of family support, the deterioration of the couple relationship and the sexual relationship significantly increased the prevalence of body image désordres. Poor tolerance of utero-vaginal surgery and brachytherapy also significantly increased the prevalence of these disorders. In multivariate analysis, low socioeconomic status was the independent protective factor for body image disorder.

Conclusion: Preventive strategies aimed at maintaining a positive body image in these women should be undertaken.

Keywords: Uterine tumors; Treatment; Body image; Couple

Introduction

The concept of the human body image was defined by Paul Schilder in 1935 as the image of our own body that we form in our mind, in other words, the way our body appears to us to ourselves [1]. It results from the set of perceptions, representations, feelings and attitudes that the individual has developed of his body through the experiences that have marked his life [2]. It is a psychosomatic representation that arises «at the crossroads of body and psyche; it covers the permanence of oneself in space, in time and in relationships with the world” [3]. Thus, body image is not only the work of oneself but also of the other who participates in its creation and can even share his experience. This image, both fragile and complex, is not innate, but is formed from early childhood. It is progressive and changes with age [4]. In 2003, Pikler and Winterowd showed an association between a good body image and a better capacity to adapt to cancer [5]. In oncology, the study of the body image focuses more on the subjective experience of the various aspects related to the image of the body in relation to the disease and the treatments than on the perceptual aspects, which seem more relevant in the context of psychopathological disorders [6]. In this context, body image disorders result from the diagnosis of cancer, loss of function, mutilation, symptoms, pain, side effects of treatment and changes in body experience. The integrity of the body is called into question by cancer and its treatments because the body that betrays, gives up and becomes a witness to the presence of the disease even after the end of treatment. This body affected by this long illness will gradually lead to decline and then to a death experienced as slow and painful [1]. When it affects the uterus, a hidden organ but associated with a very intense fantasy, cancer can upset a woman’s body image and call into question her feminine identity and her relationship as a couple. The objectives of this work were to research the prevalence of body image disorder in Tunisian women followed for uterine cancer and the factors associated with it.

Methods

We carried out a descriptive cross-sectional study involving one hundred Tunisian patients followed for non-metastatic endometrial or cervical cancer and in complete remission at the time of questioning, with a follow-up greater than six months. We passed the Body Image Scale to these patients and inquired about the different socio-demographic data. We excluded patients with a personal history of psychiatric disorders and those with significant cognitive impairment affecting comprehension of the questionnaires. The Body Image Scale (BIS) is a questionnaire developed and validated by Hopwood et al. [7] intended to assess the emotional and behavioral experience of patients on their body image, resulting from cancer and treatments, and including aspects relating to the perception of physical appearance, bodily integrity and feeling of seduction.

Result

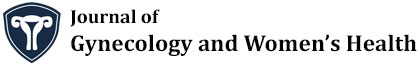

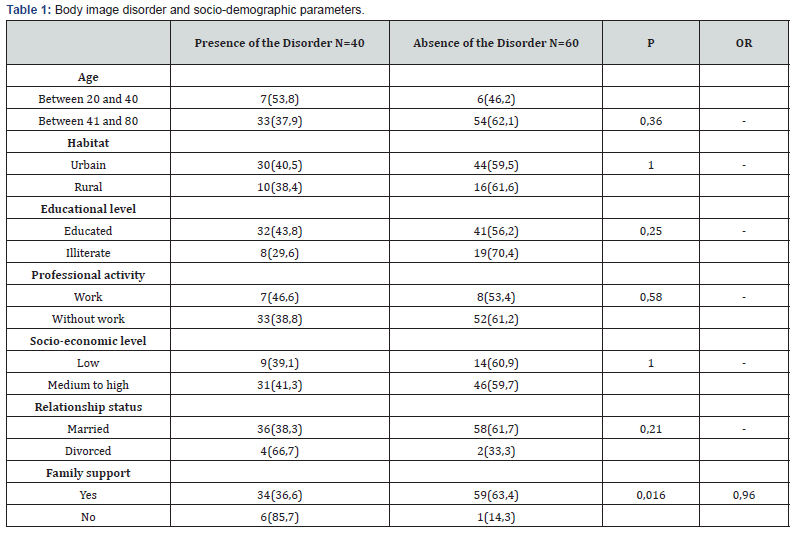

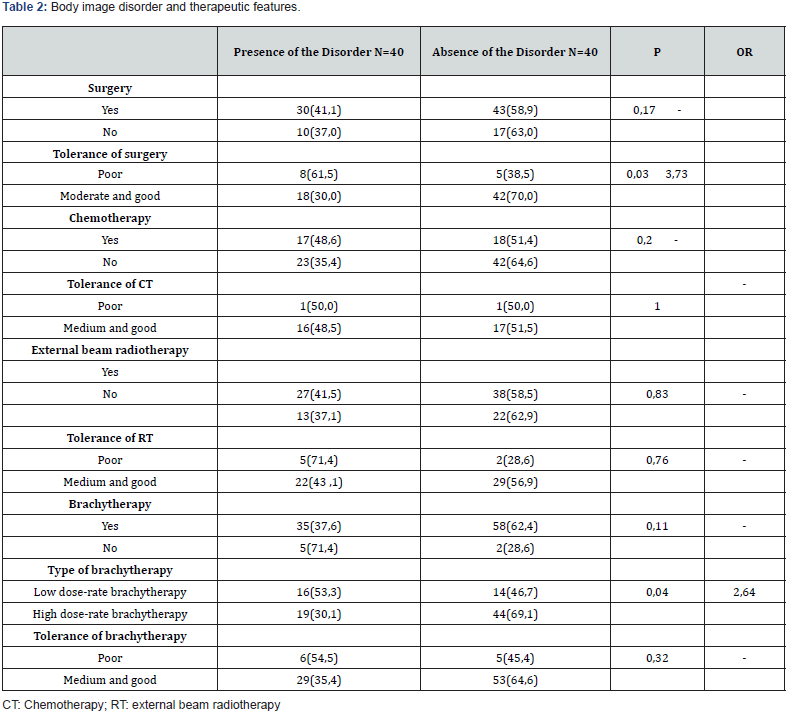

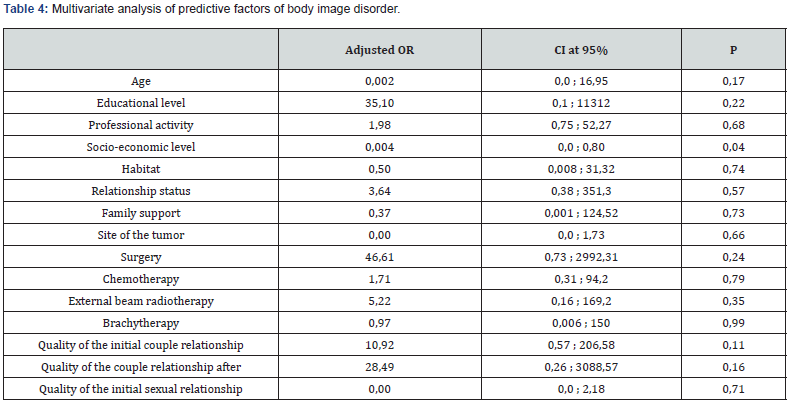

Forty-six women were followed for cervical cancer and 54 for endometrial cancer. The mean age of the patients was 53.92 years with ranges of 28 and 74 years. In our study, 40% of the patients had body image disturbances. The mean BIS score was 12.03 with extremes ranging from 0 to 30 with a standard deviation of 7.88. In univariate analysis (Tables 1-3), the absence of family support, the deterioration of the couple relationship and of the sexual relationship between the period preceding the diagnosis and that following the end of the treatment significantly increased the prevalence of body image disorders. Poor tolerance of uterovaginal surgery and brachytherapy also significantly increased the prevalence of these disorders. In multivariate analysis, low socioeconomic status was the independent protective factor for body image disorder (ORa 0.004; 95% CI [0-0.8]; p = 0.04) and sexual dysfunction was the independent predictor of this disorder (ORa 3.77; CI 95% [1.15-12.33]; p = 0.02) (Table 4).

Discussion

According to Sarramon-Bacquie et al. [8], « the uterus is an organ rich in symbolic representations. It is a symbol of femininity, sexuality and fertility. In ancient times, the Greeks and Romans had the same beliefs. The power of this organ is strong, it strikes the imagination until it is used as a name for grouping psychological manifestations under the name of hysteria. It ensures the function of menstruation which is a constitutive element of the female identity, signing for some a periodic disturbance which contributes to the maintenance of health, to a weight balance; thus, this organ appears to have a regulatory role with regard to both the body and the mind «. Indeed, if this cancer does not have an immediate physical impact, it affects women in their femininity, where becoming a woman then becomes a mother is embodied. The body changes little in the mirror, but the bodily damage is there, in the imagination and in the sensory, modifying the internal mirror from the moment the diagnosis is announced and then throughout the therapeutic course and follow-up. If the hysterectomy, for example, is not visible on the outer body, it resounds on the imaginary body like castration [9]. First, the announcement of the diagnosis can break the bodily unity. Subsequently, treatments for uterine cancer can have severe repercussions on the female body [10].

The prevalence of body image disorder

The variety and exponential number of research published in recent years demonstrated interest in the concept of altered body image in oncology [11]. The rate of its prevalence deferred from one study to another. This could be explained by the use of different assessment scores and by the divergence of cultures of the populations studied [9,12]. Although a great deal of research has focused on the relationship between dissatisfaction with body image and breast cancer [11], to our knowledge, studies that address body image specifically in cancers of localization uterine were much less. Yet Andersen and Jochimsen have shown that disturbed body image is more of a problem for patients with pelvic cancer than for those with breast cancer [13]. In our sample, we found 40% of women with body image disorders. Our result was comparable to Donovan’s study in the United States, which showed a prevalence of body image disorder of 50% in women followed for cervical cancer [14]. In a descriptive cross-sectional study done in Singapore including 104 women followed for cervical cancer or endometrial or ovarian cancer, it was shown that 37% of patients reported feeling embarrassed by their appearance, 23 % of them said they felt less physically attractive because of their cancer or treatment and 22% said they felt dissatisfied with their body [15]. It would have been interesting to situate our results not only in relation to Western studies but also in relation to Eastern studies being of different cultural, religious and social specificities. In Morocco, for example, a descriptive cross-sectional study including 110 patients with cervical cancer showed that around 34% of patients presented with a body image disorder [16]. In Tunisia, to our knowledge, there was no published work that studies body image in endometrial and / or cervical cancers. For this reason, we tried to compare the results of our study with other Tunisian studies that address breast cancer such as the study carried out by Ellouze F et al. to our institute in 2017 which showed a prevalence of 45% of alteration of the body image [17] and that of Charfi N in southern Tunisia in 2011 which showed a prevalence of 47.6% of alteration of body image [18].

Factors associated with disturbed body image

In the literature, as in our study, certain factors associated significantly with the disorder of the body image have been observed in women in the context of gynecological cancer such as family support, socio-economic level, associated tolerance to surgery, the type of brachytherapy, the quality of the couple’s relationship before and after cancer and the evolution of this relationship, the quality of sexual relationship after cancer as well as the evolution of this relationship. However, unlike our study, age, level of education, professional activity, dependent children, anxiety-depressive disorders and setback were identified.

Body image disorder and age

In our work, 53.8% of young women between the ages of 20 and 40 had a body image disorder but no statistically significant relationship. Indeed, the young age makes the woman more attentive to her body, more vulnerable to its deformations and more concerned about her femininity and her attractiveness, which exposes, when she is suffering from a cancer which mainly affects an organ with a strong emotional, symbolic and relational load, with an alteration of the perception of the image of his body [19]. Teo et al. have shown that increasing age each year is associated with a 5% reduction in the likelihood of body image distress [15].

Body image disorder and professional activity

Returning to work was seen as scary and self-image disruptive for the majority of patients in our study with no statistically significant connection. This could be explained by the fact that unemployed women would find in their homes a refuge in which to hide their physical scars and their narcissistic wounds, while working women would be confronted every day with the gaze of society, that gaze watching with curiosity and stubbornness their threatening cancerous transformations. When the stigmatized body is exposed, revealed to the gaze of those around it, the bodily landmarks are destabilized with a profound disruption of the self-image, which can go as far as self-loathing [20]. In addition, a minority of the patients who were professionally active in our study (Painter, Professor who was in the process of obtaining a doctorate during the follow-up period, flight attendant, etc.) mentioned in their speeches that their professions had helped them to be stronger, more confident and to overcome the stressful periods associated with cancer. The results of the literature on the relationship between work activity and body image in female cancers have been conflicting. According to Pinar et al. [21], in the context of gynecological cancers, women with a job, higher income, better education had a better body image. On the other hand, a Tunisian study including 100 women followed for breast cancer, a remarkable external organ, showed that professional activity was an independent predictor of an alteration in body image [22].

Body image disorder and socio-economic level

Although employment status was negatively associated with body image in some studies, there was a positive association in the same studies between better monthly family income and better body image [20]. Our study found the opposite result since in binary logistic regression, the low socioeconomic level represented an independent protective factor of the disturbance of the body image (ORa 0.004; 95% CI [0-0.8]; P = 0.04). For the wealthy socio-economic class, with easier access to beauty care, women are increasingly interested in the perfection and beauty of their body and worry about the slightest deformation that can affect it. On the other hand, for women with a low income, this aspect is of less importance. In cancer, their total focus turns to healing and survival.

Disturbed body image and the follow-up period

The prevalence of body image disorder varied in the literature depending on the timing of the screening. This disorder is said to be at its peak during the first months following the start of treatment [17]. In our study, women who had a follow-up between six months and twelve months had more body image disturbances but not statistically significant.

Body Image disorder and family

The concept of body image is strongly influenced by the interaction of patients with those around them. The family, for example, is a source of support for people with cancer (providing information, tangible help, instrumental, emotional support, help with evaluation and social affiliation). Its presence is associated with a better adaptation to gynecological cancer and a better selfimage, which is consistent with our study [17, 23,24].

The body image disorder and the tunisian couple The couple is also described as an active support for the patients. Female cancer is a real ordeal for the couple involved in their emotional, functional and sexual cohesion. It has been shown that the quality of the couple’s relationship and the patient’s basic sexuality were decisive in protecting or altering her body image, which is consistent with our study [17].

The body parts usually invested for sexuality and eroticism become objects of care, pain and suffering. The body then becomes de-eroticized and an-erogenous. He is no longer desiring, nor desired. It is no longer an object of pleasure, of pleasant and voluptuous sensations. It has been shown that couples who communicate about the disease adapt better to the changes in roles involved by it [9] because the harmony of the couple necessarily requires dialogue, sharing and mutual understanding of the issues. It is through this dialogue that the couple comes to understand the disease and the treatment and to find solutions to the disruptions in their sex life: for example abstinence or new modes of sexual relations.

In the literature, the partner’s reaction to the physical changes seen after cancer could predict the patient’s own acceptance of her appearance and sense of femininity [25]. In a cross-sectional study of married Tunisian women, it was shown that body satisfaction by their spouse seems to be a guarantee of better selfesteem, of a better quality of female sexuality in its various stages and a development of the couple [26]. With the persistence of the representation of gynecological cancer as a contagious disease in certain circles in Tunisia, the disgust of the husband or even the patient of his own body can aggravate the psychological suffering of the wife.

Body image disorder and type of treatment

All types of specific treatments performed in the management of these cancers can be experienced as devastating the body. Repeated examinations, intimate organs scrutinized to the smallest detail (palpations, gynecological examinations, imaging, and repeated biopsies) and invasive medical procedures can induce a feeling of intrusion, burglary and injury to physical integrity. The body is no longer the same and the woman may feel dispossessed of her privacy.

Surgery

Surgery was described in the literature as the type of treatment that most predicts this disorder. Removal of the uterus, this organ rich in representations, can be disruptive on several levels, particularly for self-image [10,27]. Indeed, the loss of the uterus in part or in whole sends the person back to the grieving process with an altered self-esteem. The disruption of feminine movements summons in a woman each test of reality constituting her sex: menstruation, coitus, motherhood and menopause. Some women struggle with the idea that they are no longer whole or real women following removal of their uterus, ovaries and/or cervix [28]. When menopause occurs by irradiation of the ovaries, without surgical removal, the experience is sometimes less difficult, while the objective effects remain the same. Preserving the ovaries for women, even non-functional ones, decreases the feeling of loss of femininity [29]. Surgical trauma to the pelvic autonomic nervous system during radical hysterectomy can induce various dysfunctions of the bladder and rectum. Sometimes the operated women can present post-operative voiding difficulties, most often transient [30]. Lymphedema of the lower limbs may also exist after lymph node dissection. An unsightly or tender scar and even an eventration can complicate pelvic laparotomy [31]. In our study, poor postoperative tolerance was noted in 17.8% of patients mainly due to postoperative pain and was a risk factor for body image disorder. It should be noted that other studies have shown improved body image after hysterectomy due to pain relief, embarrassing and disturbing heavy bleeding and fear of pregnancy [32]. Hysterectomy could also be a symbol of the «extraction» of disease and repossession from a healthy body.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy is responsible for several side effects: digestive disorders, weight change, general repercussions and irritation of all the bodily mucous membranes in particular those of the oral cavity, not to mention the risks of sterility and early menopause with all its climacteric symptoms and physical signs (vaginal dryness, urinary instability, fatigue and mood disorders). All of these can only contribute to profoundly altering self-esteem and quality of life and disrupting the attributes of femininity [32].

Radiotherapy

These complications can be accentuated if external radiotherapy is associated with its attendant side effects (epidermitis, skin atrophy, burns in the irradiated area, digestive disorders, urinary disorders, etc.). Post-radiation effects can decrease physical attraction and self-esteem [33]. Since fertility is synonymous with femininity, the loss of reproductive function in young women can have negative repercussions on self-image. Ovarian transposition seems to allow some young patients to maintain their ovarian function and fertility.

Brachytherapy

Low dose-rate brachytherapy significantly increased the risk of body image disturbances compared to high dose-rate brachytherapy in our study. It seems that treatment with low dose-rate brachytherapy, a treatment that involves casting, general anesthesia, the operating room, lying down in a gynecological position for several hours, surrounded by the care team, the hospitalization, isolation in a room and pain after the introduction of the equipment is particularly related to these difficulties which upset the relationship with the body and especially with sex. It is moreover the same lexical field as that of childbirth that the patients reappropriate to talk about this treatment and the post-therapeutic sensations are compared to the postpartum sensations, particularly in the perineum that women feel and describe as «released» [34]. We did not find a statistically significant relationship in our study specifically of interest to high dose-rate brachytherapy and impaired body image. The ambulatory nature of this type of brachytherapy as well as the simplicity and ease of the placement of vaginal cylinders and the treatment could explain this result.

Limitation

Our study is of interest to only a hundred patients. The power of the results of this work would have been better if we had recruited a larger workforce. It was mono-centric. However, the Salah Azaiez Institute is the benchmark oncology center for cancers in women and the cancer registry data collection center for northern Tunisia.

Conclusion

The quality of the couple’s relationship and of the sexual relationship as well as the relationship with the patients’ entourage are determining factors in improving or disrupting the image of one’s body. Our study shows that patients’ lack of communication with their partners and with the healthcare team is one of the main obstacles when it comes to recognizing and then treating these complications. Through this work, we have highlighted the lack of a screening policy and management of these problems in patients with uterine cancer during quarterly follow-up consultations. These problems, which were hidden for a long time, untreated and not followed up, could compromise all aspects of patients’ lives as well as their therapeutic management. Preventive strategies aimed at maintaining a positive body image in these women should thus be undertaken.

References

- Schdlder P (1968) L'Image du corps, étude des forces constructives de la psyché. Gallimard, Paris.

- Lantheaume S, Fernandez L, Lantheaume S, Bosset M, Pagès A, et al. (2016) Cancer du sein, image du corps et psychothérapie par médiation photographique. Ann Med Psychol174(5):366-373.

- Sanglade A (1983) Image du corps et image de soi au Rorschach. Psychol Fr28(2):104-111.

- White CA (2000) Body image dimensions and cancer:aheuristic cognitive behavioural model. Psychooncology9(8):183-192.

- Pikler V, Winterowd C (2003) Racial and body image differences in coping for womendiagnosedwithbreast cancer. Health Psychol22(6):632-637.

- Hopwood P (1993) The assessment of body image in cancer patients. Eur J Cancer29A(2):276- 281.

- Hopwood P, Fletcher I, Lee A, Al Ghazal S (2001) A body image scale for use with cancer patients. Eur J Cancer37(2):189-197.

- Sarramon-Bacquie C, Bethieux L, Schmitt L (2000) Problématique féminine en psychiatrie: Conséquences psychopathologiques de l'hysté Masson, Paris.

- Venturini E (2009) L’impact du cancer pelvien sur la sexualité et le couple: ce que nous apporte la littérature. Psychooncology3(3):188-199.

- Hawighorst S, Fusshoeller C, Franz C, Trautmann K, Schmidt M, et al. (2004) The impact of treatment for genital cancer on quality of life and body image results of a prospective longitudinal 10 yearstudy. GynecolOncol94(2):398-403.

- Charles C, Dauchy S (2011) Étudier l’image du corps en oncologie: un point sur la méthodologie de recherche. Bull Cancer98(10):1209-1220.

- Reich M (2009) Cancer et image du corps: identité, représentation et symbolique. Info Psy85(3):247-254.

- Andersen BL, Jochimsen PR (1985) Sexualfunctioningamongbreast cancer, gynecologic cancer, and healthywomen. J Consult Clin Psychol53(1):25-32.

- Donovan KA, Taliaferro LA, Alvarez EM, Jacobsen PB, Roetzheim RG, et al. (2007) Sexualhealth in womentreated for cervical cancer:characteristics and correlates. GynecolOncol104(2):428-434.

- Teo I, Cheung YB, Lim TYK, Namuduri RP, Long V, et al. (2018) The relationshipbetweensymptomprevalence, body image, and quality of life in Asian gynecologic cancer patients. Psychooncology27(1):69-74.

- Khalil J, Bellefqih S, Sahli N, Afif M, Elkacemi H, et al. (2015) Impact of cervical cancer on quality of life:beyond the short term. GynecolOncolRes Pract2(1):7.

- Ellouze F, Marrakchi N, Raies H, Sana M, Amel M, et al. (2018) Le trouble de l’image du corps chez 100 femmes tunisiennes atteintes d’un cancer du sein. Bull Cancer105(4):350-356.

- Charfi N (2011) Qualité de vie et sexualité après cancer du sein [Mémoire]. Médecine, Sfax, 44, p.19.

- Pruis TA, Janowsky JS (2010) Assessment of body image in younger and olderwomen. J GenPsychol137(3):225-238.

- Chang O, Choi EK, Kim R, Nam SJ, Lee JE, et al. (2014) Association betweensocioeconomicstatus and alteredappearancedistress, body image, and quality of life amongbreast cancer patients. Asian Pac J Cancer P15(20):8607-8612.

- Ayhan A (2012) The effects of hysterectomy on body image, self-esteem, and marital adjustment in Turkish womenwithgynecologic cancer. Clin J OncolNurs16(3):99-104.

- Marrakchi N (2017) Cancer du sein: dépression, anxiété, image du corps et sexualité chez 100 femmes tunisiennes [Thèse]. Médecine, Tunisia,77:16.

- Pinar G, Okdem S, Buyukgonenc L, Ayhan A (2012) The relationshipbetween social support and the level of anxiety, depression, and quality of life of Turkish womenwithgynecologic cancer. Cancer Nurs35(3):229-235.

- Scott JL, Kayser K (2009) A review of couple based interventions for enhancingwomen’ssexualadjustment and body image after cancer. Cancer J15(1):48-56.

- Masmoudi J, Feki I, Trigui D, Bouassida M, Mnif L, et al. (2014) Perception de l’image du corps et sexualitéféminine: enquête auprès de 100 femmes tunisiennes. Sexologies23(3):107-112.

- Ibarissen Y (2018) Aspect psychosomatique de l'hystérectomie, quel impact sur la sexualité? Étude de 05 cas au niveau de l'hôpital d'Amizour [Mémoire]. Médecine, Bejaia, p. 112.

- Cleary V, Hegarty J, Mccarthy G (2011) Sexuality in Irish womenwithgynecologic cancer. OncolNurs Forum 38(2):87-96.

- Beltran L (2013) Hystérectomie: le point de vue du psychologue. Psychooncology(378-379)29:44- 45.

- Pieters Q, Maas C, Ter Kuile M, Lowik M, Vaneijkeren M, et al. (2006) An observational longitudinal study to evaluate miction, defecation, and sexualfunctionafter radical hysterectomywithpelviclymphadenectomy for early-stage cervical cancer. Int J Gynecol Cancer16(3):1119-1129.

- Vignes S (2019) Vivre avec un lymphœdè J Med Vasc44(2):112-118.

- Yazbeck C (2004) La fonction érotique après hysté GynecolObstetFerti32(1):49-54.

- Fornier MN, Modi S, Panageas KS, Norton L, Hudis C, et al. (2005) Incidence of chemotherapyinduced, longtermamenorrhea in patients withbreastcarcinomaage 40 years and youngerafter adjuvant anthracycline and taxane. Cancer104(8):1575-1579.

- Leroy T, Flandin IG, Habold D, Hannoun JM (2012) Impact de la radiothérapie sur la vie sexuelle. Cancer Radiother16(5-6):377-385.

- Venturini E, Giacomoni C, Hoarau H, Conri V (2012) Impact du cancer gynécologique sur la sexualité féminine. Psychooncology6(3):151-162.