Use of Erotic Abilities in Sexually Functional and Dysfunctional Women - Comparative Study and Correlation with Sexual Awareness and Assertiveness

Amandine Edard1*, Stéphane Rusinek2 and Françoise Adam3

1Doctoral student in Psychology Univ. Lille, University in Villeneuve-d’ Ascq, France

2Research director, University Professor in Psychology of Emotions, University in Villeneuve-d’ Ascq, France

3Doctor in psychology and Teacher at the Catholic University of Louvain, University in Ottignies-Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium

Submission: November 06, 2020;Published: November 19, 2020

*Corresponding author: Amandine Edard, Doctoral student in Psychology Univ. Lille, University in Villeneuve-d’ Ascq, France

How to cite this article: Amandine E, Stéphane R, Françoise A. Use of Erotic Abilities in Sexually Functional and Dysfunctional Women - Comparative Study and Correlation with Sexual Awareness and Assertiveness. J Gynecol Women’s Health. 2020: 20(2): 556034. DOI: 10.19080/JGWH.2020.19.556034

Summary

Clinically, it’s interesting to see how the cognitive and behavioral abilities, and feelings of sexually functional women differ from the dysfunctional ones. The present study aims to show that this clinical hypothesis is supported by a scientific reality: women do not use these erotic abilities in the same way, whether they have sexual dysfunctions or not. 224 women aged 21 to 60, completed questionnaires on sexual functioning, sexual awareness and use of erotic abilities. Women without sexual dysfunction are significantly more sexually satisfied (p < .001), more sexually aware and assertive (p < .001), and make greater use of erotic cognitive and behavioral abilities and report more positive feelings (positive emotions and sexual feelings; p < .001), than women with sexual dysfunction. However, there is a positive correlation between erotic abilities and sexual awareness and assertiveness (p < .001). In conclusion, our study highlights the importance of the use of cognitive erotic abilities and positive feelings, already highlighted in the literature, in order to promote sexual functionality. It also highlights the importance of the use of erotic behavioral abilities in sexual functionality.

Keywords:Female sexuality; Sexual satisfaction; Sexual functioning; Erotic abilities; Sexofunctional Therapy; Sexual awareness; Sexual assertiveness

Introduction

In France, 55% of women experience or have already experienced sexual dysfunction [1], and 31% consider themselves to be sexually dissatisfied [2]. Sexual health is defined by the World Health Organization [3] as « a state of physical, mental and social well-being in relation to sexuality. It requires a positive and respectful approach to sexuality and sexual relationships, and the opportunity to have pleasurable sexual experiences, safely and without coercion, discrimination or violence » (p.3). It should be noted that sexually dysfunctional people are generally less happy [4], have lower self-esteem, a lesser feeling of well-being [5] and have increased marital stress [6,7].

Sexual satisfaction is an essential component of sexual health [8]. The final stage of the sexual response cycle [9,10], it is defined as « an affective response resulting from the subjective evaluation of the positive and negative dimensions associated with sexual activity » [11]. In general, the more a woman perceives herself to be sexually dysfunctional, the less sexual satisfaction she will experience [12]. Sexual satisfaction is also associated with improved physical and psychological status [13,14] increased sexual frequency [15-17], improved sexual communication [18], and increased relationship satisfaction [19,20].

Sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction are closely linked [8,17,21], and both are integrated into the sexual functionality model of Sexofunctional therapy [22]. This sex therapy practice emphasizes the importance of sexual functionality, a manner that works for the patient. The model of sexual functionality integrates « all the healthy and adequate sexual functions of the human being » [23]. This model, used in the treatment of sexual dysfunction, postulates that individuals develop more or less erotic abilities that promote sexual functionality. In this way, it proposes that sex therapists help patients suffering from sexual dysfunction towards the development of these abilities. For example, the teaching of the fore and aft pelvic roll allows a mobilization of the internal musculature, essential to the rise of sexual arousal, as well as a support on the internal and external erogenous parts of the female sexual organs. This roll is also more favorable to abdominal breathing, which also facilitates the excitatory rise through the combination of movements of the internal organs and the contraction/release of the internal musculature. Thus, sexual dysfunctions would be improved by the development of certain erotic abilities. Previous research has been able to identify the cognitions, behaviors and feelings present in sexually satisfied women as opposed to sexually dissatisfied women, and this in different phases of sexuality [24]. Cognitively, sexually satisfied women report significantly more positive cognitions related to sexual stimuli (e.g. sexual situation, body sensations, or erotic imagination) than sexually dissatisfied women. At the behavioral level, sexually satisfied women report more diverse sexual behaviors, more self-stimulation and a more enterprising and determined perception of themselves, using pelvic roll and pelvic floor muscles, in contrast to sexually dissatisfied women. Finally concerning feelings, sexually satisfied women do not spontaneously report any unpleasant emotions or sensations. They report an emotion of fullness, as well as several pleasant body sensations during the different phases of sexuality. The objective of the present study is to compare women without sexual dysfunction to women with sexual dysfunctions regarding the use of erotic abilities that promote sexual functionality.

Cognitive Factors Influencing Female Sexual Functioning

Many authors have studied the impact of thoughts on female sexual functioning. In 1971, Master and Johnson proposed the term ‘spectatoring’, to refer to observing one’s own sexual activity and sexual reactions, rather than being immersed in the sensory aspects of sexuality, in other words savoring the sexual sensations generated by sexual activity. Thus, several authors have highlighted a link between lack of interoceptive awareness, the ability to feel internal sensations accurately, and the presence of sexual dysfunction [15,25-27]. Some authors [28] have noted that dysfunctional women have higher alterations in genital perceptions than sexually functional women (p < .05).

Barlow [29] introduced the concept of “cognitive interference” to explain the fact that people with sexual difficulties tend to focus their attention on non-erotic and non-sexual stimuli. In the same perspective, Beck and Baldwin [30] observed how women without sexual difficulties increase or decrease their sexual arousal when they watch an erotic movie. According to this study, they focus their attention on sexual thoughts or fantasies to increase their sexual arousal and on negative and non-sexual thoughts to decrease it. Nobre and Pinto-Gouveia [31-33] were interested in the content of thoughts present during sexual activities. According to these authors, negative thoughts - especially thoughts of failure, non-erotic and sexual abuse - are significantly correlated with a lower level of sexual arousal (p < .001).

Cognitive interference is also reported to have a negative impact on sexual self-esteem, sexual satisfaction, subjective and physiological arousal and consequently on achieving orgasm [34-39]. Indeed, several studies report that sexually functional women focus their attention to the erotic context, which increases sexual desire and response [40-42]. During dyadic sexual activity, anorgasmic women also appear to use their erotic thoughts less than orgasmic women (p < .05). In addition, thinking about their body sensations is reported to be the most favorable way to achieve orgasm (p < .01), reported by orgasmic women [43].

Behavioral Factors Influencing Women Sexual Functioning

A study [44] of 2250 men and women aged 18 to 74 years, reports that sexual satisfaction is positively correlated with socalled “more liberal” sexual attitudes (p < .001), such as the use of multiple positions, manual stimulation of the genitals during coitus, and the practice of oral and anal sex. Another survey of 556 students found that sexual satisfaction was correlated with regular masturbation [45,46]. The most sexually satisfied women also show more frequent affectionate (p < .001) and sexual (p < .001) behaviors towards their partners [47]. In addition, women who achieve orgasm use more varied erotological behaviors than anorgasmic women, such as the combination of different stimulations during sexual activities [43]. Furthermore, sexual assertiveness, a tendency to assert oneself in the sexual aspects of one’s life [48], is an important predictor of sexual satisfaction [49-51] and sexual functioning [8,52]. In other words, the more assertive women are in their sexuality, the more satisfied and sexually functional they are. Finally, it is important to note that individuals with sexual dysfunction are more likely to avoid sexual relations [53], and are more passive during sexual activities [54,55].

Emotional Factors Influencing Women Sexual Functioning

If exposed to eroticism, individuals with sexual difficulties report significantly more negative affect [56,57]. On the other hand, the induction of negative affect in subjects with no sexual dysfunction produces a delay in the onset of subjective sexual arousal [58]. Nobre and Pinto-Gouveia [59,60] were able to show that sadness (p < .01), guilt (p < .001) and anger (p < .05) are significantly associated with female sexual dysfunction, and negatively correlated with pleasure (p < .001) and sexual satisfaction (p < .001). Numerous studies [27,61-65] have examined the impact of anxiety on women’s sexuality. They found that women with high levels of anxiety have more sexual distress, alterations in sexual functioning (e.g., pain, difficulty getting aroused, avoidance of sexual activities) and less sexual satisfaction. In women, anxiety is generally linked to performance demands and/or negative evaluations of their physical appearance [66-69], or to their sexual desires that they evaluate themselves as shameful [70,71]. Guilt is also strongly and negatively associated with sexual satisfaction [73,74] and sexual functioning [4,31,73,75].

In the literature, a number of abilities have already been linked to sexual functioning and satisfaction, such as attention directed towards erotic thoughts, sexual awareness, use of erotic imagination, sexual assertiveness, or the presence of positivelyvalued emotions. However, no research to our knowledge has focused on behavioral abilities, meaning the way women use their bodies during sexual activities. We are talking here about body mobility, use of muscle tone and breathing, as proposed in some sexual therapies, such as Sexofunctional Therapy.

Our first research hypothesis postulates that women without sexual dysfunction have better sexual functioning, including better sexual satisfaction, than women with sexual dysfunctions. Our second research hypothesis is that women without sexual dysfunction have more sexual awareness and sexual assertiveness than women with sexual dysfunctions. Our third hypothesis is that women without sexual dysfunction have more erotic abilities than women with sexual dysfunctions. Finally, our fourth hypothesis is that the more erotic abilities a woman has, the better her sexual awareness and sexual assertiveness.

Materials and Method

Recruitment and participants

Participants were recruited on a voluntary basis between February 12 and September 14, 2018. A call for participants entitled “Women’s Sexuality in the 21st Century” was posted on various sites and emailed to our contacts with the proposal to disseminate it widely. After reading the presentation page of the research in progress, mentioning the contact information of the person in charge of the study, the confidentiality information, as well as the fate of the results, each participant signed a free and informed consent document. A total of 288 Francophone women completed this online survey. Inclusion criteria included (1) being female and (2) being at least 18 years of age. After removing the responses of women who did not complete the entire questionnaire, 224 women between the ages of 21 and 60 participated in the study.

Measures

Socio-demographic questionnaire: This questionnaire consists of twelve socio-demographic items. These are personal items (their age range), about their emotional life (marital status, length of current relationship) and sexual life (sexually active, sexual orientation). Each item consists either of a dichotomous choice (yes or no, alone or in couple) or of numerical data: “number of years”.

Female sexual function index: The Female Sexual Functioning Index (FSFI – [76] assesses the main dimensions of female sexual function according to 6 dimensions: desire (2 items), arousal (4 items), lubrication (4 items), orgasm (3 items), sexual satisfaction (3 items), and pain (3 items). This self-report questionnaire is composed of 19 items to be answered using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (no sexual activity) to 5 (very high or very often), or from 1 (almost never or never) to 5 (almost always or always). To calculate the score for each subscale, the scores for each item are added together and then multiplied by the subscale coefficient. The total score is calculated by adding the scores on the 6 subscales. A total score below 26.55 corresponds to the presence of sexual impairment [77,78]. The scale validation study showed high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .86. This reliability was confirmed in our sample with a Cronbach’s alpha of .93. The Cronbach alphas of the subscales range from .86 to .95. This tool is therefore a reliable measure for discriminating between functional and sexually dysfunctional women.

Sexual awareness questionnaire: The Sexual Awareness Questionnaire (SAQ – [48] is a 36-item self-report questionnaire that assesses sexual awareness and assertiveness on four dimensions: (1) sexual awareness, defined as knowing one’s own sexual functioning (items: 1, 4, 10, 13, 22 and 25); (2) sexual surveillance refers to the judgment of one’s own sexuality (items : 2, 5, 14, 17, 23, 26, 28, 31, 32); (3) sexual assertiveness, defined as the tendency to assert oneself in the sexual aspects of one’s life (items: 3, 6, 9, 12, 15, 18, 24); and, (4) awareness of sexual attractiveness (items: 8, 11, 29). Participants rate themselves on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (not at all characteristic of me) to 5 (very characteristic of me). Items 6, 9, 23, 30, 31, 32 are to be reversed. In this study, only the sexual awareness and sexual assertiveness subscales were used. The scale validation study showed high internal consistency with a Cronbach’s alpha of .81. This reliability was confirmed in our sample with a Cronbach’s alpha of .86 for sexual awareness and .76 for sexual assertiveness.

Erotic abilities questionnaire: A 32-item self-report questionnaire was developed, based on previous research (Edard & Rusinek, submitted). These items were obtained by interviewing sexually satisfied and sexually dissatisfied women in a semistructured interview. Focusing on their practices during sexuality, three main themes were questioned: their cognitions and erotic thoughts, their behaviors and body movements, and finally their emotions and body sensations. The questionnaire is composed of three dimensions : cognitive (items 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 15, 19, 22, 27), referring to the ability to focus attention on sexual stimuli, such as the sexual situation, or the use of erotic imagination ; behavioral (items 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 14, 25, 28, 31), referring to all behaviors that carry the individual’s sexual arousal, such as double roll (pelvishead), the use of abdominal breathing or the use of pelvic floor muscles ; and positive feelings (items 13, 16, 17, 18, 20, 21, 23, 24, 26, 29, 30, 32), referring to positive-valued emotional feelings and the perception of sexual sensations.

Answers should be given on a 4-point Likert scale, ranging from 0 (not true for me at all) to 3 (true for me at all). Items 3, 6, 19 and 25 should be reversed. The score of the 3 sub-scales is calculated by adding the scores of each item. A total score can be calculated by adding the scores of the 3 dimensions. The erotic abilities scale showed a high internal consistency in our sample with a Cronbach’s alpha of .84 for the total score. Cronbach’s alphas of the 3 dimensions are satisfactory, with .69 (cognitive), .57 (behavioral) and .58 (emotional).

Results

Descriptive Analyses

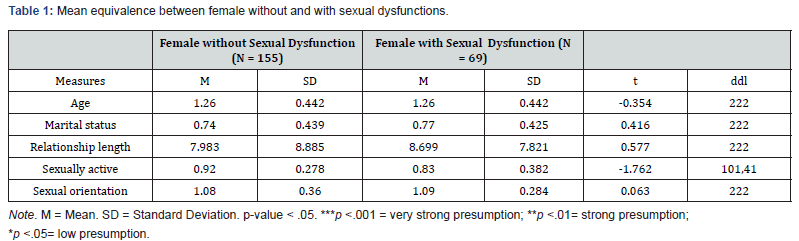

Participants were aged 21 - 40, 72.3% (N=162) and 41-60, 27.7% (N=62). Most of the women are in a relationship, 75% (N = 168) and 25% are single (N = 56). The majority have children, 63.4% (N = 142) versus 36.6% (N = 82) do not have children. Moreover, 88.8% of women are sexually active (N = 199), and only 11.2% are inactive (N = 25). The vast majority of women report being heterosexual, 87.9% (N = 197). The others report being bisexual, 10.3% (N = 23) or homosexual, 1.8% (N = 4). According to the FSFI cut-off [76], the sample was separated into two groups: (1) women without sexual dysfunction, 69.2% (N = 155) and (2) women with sexual dysfunction, 30.8% (N = 69). Descriptive analyses revealed no significant differences between these two groups with respect to age, being in a couple, being sexually active, or sexual orientation (Table 1).

Statistical Analyses

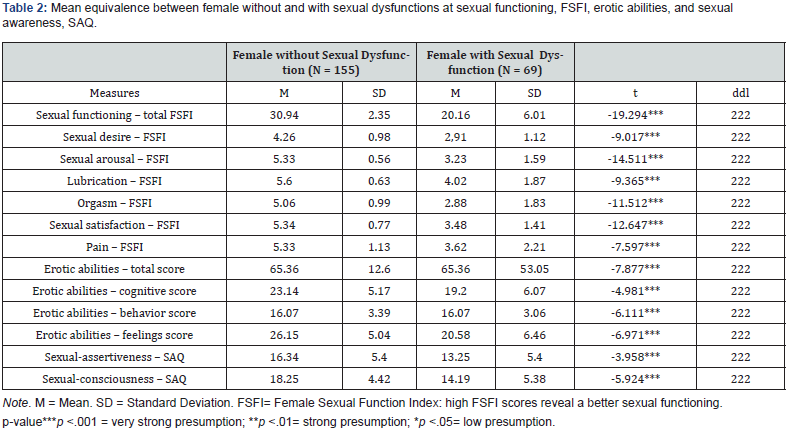

After checking the normality of the variables (e.g., Kurtosis and Skewness), we performed correlation analyses (e.g., Pearson’s r) and mean comparisons (e.g., Student’s t) using SPSS 25 (Table 2).

H1: Women without sexual dysfunction have better sexual functioning, including better sexual satisfaction than women with sexual dysfunctions.

Women without sexual dysfunction have significantly higher total sexual functioning score than women with sexual dysfunction (p < .001). They also have significantly more desire, arousal, lubrication, orgasm, sexual satisfaction, and less pain than women with sexual dysfunctions (p < .001).

H2: Women without sexual dysfunction have higher scores for sexual awareness and sexual assertiveness than women with sexual dysfunctions.

As before, we compared the scores on the sexual awareness and sexual assertiveness scales for women without sexual dysfunction with those of women with sexual dysfunctions. Women without sexual dysfunction had more sexual awareness and sexual assertiveness than women with sexual dysfunctions (p < .001).

H3: Women without sexual dysfunction have more erotic abilities than women with sexual dysfunctions.

Women without sexual dysfunction have a significantly higher total erotic abilities score than women with sexual dysfunctions (p < .001). They also have better scores on cognitive (p < .001), behavioral (p < .001) and positive feelings (p < .001) dimensions than women with sexual dysfunctions.

H4: The more erotic abilities a woman has, the better her ability to be sexually aware and assertive.

There is a small but significant positive relationship between total erotic abilities score and sexual assertiveness (r = .224; p < .001). On the other hand, there is also a moderate and significant positive relationship between total erotic abilities score and sexual awareness (r = .404; p < .001).

Discussion

This study helps us to better understand the importance of the use of erotic abilities in female sexual functioning. As a reminder, our first hypothesis was that women without sexual dysfunction are also the most sexually satisfied. From the analyses, we can see that women without sexual dysfunctions have more sexual desire, sexual arousal, lubrication, orgasm, less pain and are more satisfied than women with sexual dysfunctions. This is consistent with research that shows a significant positive association between sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction [8,17,21]. The latter is one of the important dimensions of sexual function [76], and the more positively a woman assesses other dimensions of her sexuality (e.g., sexual desire, sexual arousal, lubrication, orgasm, and no pain), the more sexually satisfied she is Our second hypothesis, that women without sexual dysfunction have higher capacity for sexual awareness and sexual assertiveness, has been validated. In our study, women who are able to recognize their sexual preferences, sexual sensations, or what arouses them sexually, can more easily focus their attention on these pleasurable stimuli. In contrast, women with sexual dysfunctions have less sexual awareness. These findings are supported by previous research on this subject ([15,25,26,28,40,43]. Our study also showed that women who do not have sexual dysfunction are also more assertive in their sexuality. Indeed, a woman who informs her partner about how she functions is more likely to have her sexual needs met. This information is congruent with other research conducted on the subject [49,50,51,52,76].

Our third hypothesis focused on the fact that women without sexual dysfunction use more erotic abilities than women with these difficulties. According to our analyses, women without sexual dysfunction use more erotic abilities in general, and more specifically more cognitive, behavioral and positive feelings erotic abilities, than women with sexual dysfunctions. Our results replicate previous research [31-33, 40, 43-46, 59, 62-65,72] on factors influencing sexual functioning or satisfaction achieved to date, and support the model proposed by Sexofunctional Therapy. This research confirms the fact that women without sexual dysfunction and sexually satisfied use their erotic imagination more and focus more attention to erotic and sexual stimuli than women with sexual dysfunctions. This tendency to increase sexual arousal allows them to feed their sexual desire, increase lubrication and achieve orgasm.

Inspired by the Sexofunctional Therapy, the originality of this study focuses on the influence of body use on sexual functionality. Indeed, our analyses show that women without sexual dysfunction tend to use more behavioral erotic abilities that are favorable to sexual functionality than women with sexual dysfunctions. To our knowledge, the impact of these behaviors on sexual functionality or satisfaction has not been studied until today. As a continuation of this research, the evaluation of the use of the body in women’s sexuality and the learning of new behaviors that promote sexual functionality could be the subject of futures researches.

Our results also show that sexually functional women perceive more positive feelings, both emotional and sexual. This conclusion is in line with work on the subject [27,43,58,61-65], as well as with the Sexofunctional approach.

Finally, our last hypothesis was that women who use more erotic abilities show more sexual awareness and sexual assertiveness. According to our results, there is indeed a positive correlation between the use of erotic abilities and the capacities of sexual awareness and sexual assertiveness. The use of cognitive, behavioral and emotional erotic abilities that promote sexual functionality requires sexual awareness and sexual assertiveness. Further research could be conducted to shed more light on the relationship between sexual awareness and assertiveness and women’s erotic abilities.

Conclusion

This study replicates previous researches, particularly regarding cognitive, emotional and attention to pleasurable sensations during women’s sexual activities. Our study also highlights the importance of behavioral erotic abilities, which have been ignored in the scientific literature. The questionnaire evaluating the use of these erotic abilities in women’s sexuality could be validated in future research. This tool could then be used in scientific research as well as in clinical practice. Furthermore, as we did in this research, proposing a set of erotic abilities that improve female sexual functioning, allows us to envisage a model of female sexual functionality, as proposed in Sexofunctional Therapy, which could be the subject of a future study. To conclude, in order to confirm the hypothesis that the development of erotic abilities would improve female sexual functionality, a future line of research could propose and test a treatment protocol based on the development of these erotic abilities in women suffering from sexual dysfunctions.

References

- Colson M, Lemaire A, Pinton P, Hamidi K, Klein P, et al. (2006) Sexual behaviors and mental perception, satisfaction and expectations of sex life in men and women in France. J Sex Med 3(1): 121-131.

- Ifop (2018) Enquête Ifop publiée à l’occasion de la journée mondiale de l’ Observatoire Européen e la Sexualité Féminine.

- World Health Organization (2010) Measuring Sexual Health: Conceptual and practical considerations and related indicators. WHO Document Production Services, Geneva.

- Laumann EO, Gagnon JH, Michael RT, Michaels S (1995) The social organization of sexuality: Sexual practices in the United States. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Heiman JR (2002) Psychologic treatments for female sexual dysfunction: Are they effective and do we need them? Archives of Sexual Behavior 31(5): 445-450.

- Bartlik B, Goldberg J (2000) Female sexual arousal disorder. Dans S Leiblum, R Rosen (Eds.), Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. Guilford Press, New York, p. 85-117.

- Pridal CG, LzPiccolo J (2000) Multielement treatment of desire disorders. Dans SR. Leiblum RC, Rosen (Eds.), Principles and Practice of Sex Therapy. In: (3rd Edn.), Guilford Press, New-York, p. 57-81.

- Meston CM, Trapnell P (2005) Development and validation of five-factor sexual satisfaction and distress scale for women: the sexual satisfaction scale for women (SSS-W). J Sex Med 2(1): 66-81.

- Basson R (2001a) Human Sex-response cycles. J Sex Marital Ther 27(1): 33-43.

- Sierra JC, Buela-Casal G (2004) Evaluacion y tratamiento de las disfunciones sexuales. In: Buela-Casal G, Sierra JC (Eds.), Manual de evaluacion y tratamientos psicologicos. In: (2e edn), Biblioteca Nueva, Madrid, p. 439-485.

- Lawrence K, Byers ES (1995) Sexual satisfaction in long-term heterosexual relationships: The interpersonal exchange model of sexual satisfaction. Personal relationships 2(4): 267-285.

- Chang SCH, Klein C, Gorzalka BB (2013) Perceived prevalence and definitions of sexual dysfunction as predictors of sexual function and satisfaction. J Sex Res 50(5): 502-512.

- Brody S, Costa RM (2017) Vaginal orgasm is associated with indices of women’s better psychological, intimate relationship, and psychophysiological function. Canadian journal of human sexuality 26(1): 1-4.

- Scott VC, Sandberg JG, Harper JM, Miller RB (2012) The impact of depressive symptoms and health on sexual satisfaction for older couples: Implications for clinicians. Contemporary Family Therapy 34(3): 376-390.

- Baumeister RF, Catanese KR, Vohs KD (2001) Is there a gender difference in strength of sex drive? Theorical views, conceptual distinctions, and a review of relevant evidence. Personnality and Social Psychology Review 5(3): 242-273.

- McNulty JK, Fisher TD (2008) Gender differences in response to sexual expectancies and changes in sexual frequency: A short-term longitudinal study of sexual satisfaction in newly married couples. Arch Sex Behav 37(2): 229-240.

- Smith A, Lyons A, Ferriz J, Richters J, Pitts M, et al. (2011) Sexual and relationship satisfaction among heterosexual men and women: The importance of desired frequency of sex. J Sex Marital Ther 37(2): 104-115.

- Byers ES (2011) Beyond the birds and the bees and was it good for you? Thirty years of research on sexual communication. Canadian Psychology 52(1): 20-28.

- Sprecher S, Christopher FS, Cate R (2006) Sexuality in close relationship. In: Dans AL, Vangelisti, Perlman D (Eds.), The Cambridge Handbook of Personal Relationship. Cambridge University Press, New-York, p. 463-482.

- Rubin H, Campbell L (2012) Day-to-day changes in intimacy predict heightened relationship passion, sexual occurrence, and sexual satisfaction: A dyadic diary analysis. Social Psychological and Personality Science 3(2): 224-231.

- Heiman JR, Long JS, Smith SN, Fisher WA, Sand MS, et al. (2011) Sexual satisfaction and relationship happiness in midlife and older couples in five countries. Arch Sex Behav 40(4): 741-753.

- De Carufel F (2012b) La fonctionnalité Formation en Thérapie Sexofonctionnelle, Paris 5ème.

- De Carufel F (2010) La thé Les fondements théoriques. Consulté sur.

- Edard A, Rusinek S (2020) Étude exploratoire des habiletés érotiques en jeu dans la pratique sexuelle des femmes. Étude qualitative auprès d’une population de femmes satisfaites sexuellement versus insatisfaites. Sexologies.

- Brody S (2007) Intercourse orgasm consistency, concordance of women’s genital and subjective sexual arousal, and erotic stimulus presentation sequence. J Sex Marital Ther 33(1): 31-39.

- Chivers ML, Seto MC, Lalumière ML, Laan E, Grimbos T, et al. (2010) Agreement of self-reported and genital measures of sexual arousal in men and women: a meta-analysis. Arch Sex Behav 39(1): 5-56.

- Laan E, Everaerd W, Aanhold VM, Rebel M (1993) Performance demand and sexual arousal in women. Behav Res Ther 31(1): 25-35.

- Callens N, Bronselaer G, De Sutter P, De Cuypere G, T’Sjoen G, et al. (2016) Costs of pleasure and the benefits of pain: self-perceived genital sensation, anatomy and sexual dysfunction. Sexual Health 13(1): 63-72.

- Barlow DH (1986) Causes of sexual dysfunction: the role of anxiety and cognitive interference. J Consult Clin Psychol 54(2): 140-148.

- Beck JG, Baldwin LE (1994) Instructional control of female sexual responding. Arch Sex Behav 23(6): 665-684.

- Nobre PJ, Pinto-Gouveia J (2006a) Dysfunctional sexual belief as vulnerability factors to sexual dysfunction. J Sex Res 43(1): 68-75.

- Nobre PJ, Pinto-Gouveia J (2008a) Differences in automatic thoughts presented during sexual activity between sexually functional and dysfunctional males and females. Journal of Cognitive Therapy and Research 32(1): 37-49.

- Nobre PJ, Pinto-Gouveia J (2008b) Cognitive and emotional predictors of female sexual dysfunctions: preliminary findings. J Sex Marital Ther 34(4): 325-342.

- Anderson AB, Rosen NO, Price L, Bergeron S (2016) Associations between penetration cognitions, genital pain, and sexual well-being in women with provoked vestibulodynia. J Sex Med 13(3): 444-452.

- Beck JG, Barlow DH (1987) The effect of anxiety and attentional focus on sexual responding-II: cognitive and affective patterns in erectile dysfunction. Behavior research and therapy 24(1): 19-26.

- Cuntim M, Nobre P (2011) The role of cognitive distraction on female orgasm. Sexologies 20(4): 212-214.

- Dove NL, Wiederman MW (2000) Cognitive distraction and women’s sexual functioning. J Sex Marital Ther 26(1): 67-78.

- Prause N, Janssen E, Hetrick WP (2008) Attention and emotional responses to sexual stimuli and their relationship to sexual desire. Arch Sex Behav 37(6): 934-949.

- Pujols Y, Meston C, Seal B (2009) The association between sexual satisfaction and body image in womenJ Sex Med 57(2): 905-916.

- Géonet M, De Sutter P, Zech E (2013) Les facteurs cognitifs dans le désir sexuel hypoactif fé Sexologies 22(1): 10-18.

- Nutter DE, Codron MK (1983) Sexual fantasy and activity patterns of females with inhibited sexual desire. J Sex Marital Ther 9(4): 276-282.

- Wilson GD, Lang RJ (1981) Sex differences in sexual fantasy patterns. Personality and Individual Differences 2(4): 343-346.

- De Sutter P, Day J, Adam F (2014) Qui sont les femmes orgasmiques? Etude exploratoire sur un échantillon de femmes francophones tout venant. Sexologies 23(3): 93-100.

- Haavio-Mannila E, Kontula O (1997) Correlates of increased sexual satisfaction. Arch Sex Behav 24(4): 399-419.

- Davidson JK, Moore NB (1994) Guilt and lack of orgasm during sexual intercourse: myth versus reality among college women. Journal of Sex, Education and Therapy 20(3): 153-174.

- Hogarth H, Ingham R (2009) Masturbation among young women and associations with sexual health: an exploratory study. J Sex Res 46(6): 558-567.

- Renaud C, Byers ES, Pan S (1997) Sexual relationship satisfaction in mainland China. Journal of Sexual Research 34(4): 399-410.

- Snell WE, Fisher TD, Miller RS (1991) Development of the sexual awareness questionnaire: Components, reliability, and validity. Annals of Sex Research 4(1): 65-92.

- Carrobles JA, Gamez-Guadix M (2011) Funcionamiento sexual, satisfaccion sexual y bienestar psicologico y subjetivoen una muestra de mujeresEspanolas. Anales de Psicologia 27(1): 27-34.

- Hurlbert DF, Apt C, Rabehl SM (1993) Key variables to understanding female sexual satisfaction: an examination of women in non distressed marriages. J Sex Marital Ther 19(2): 154-165.

- MacNeil S, Byers E (1997) The relationships between sexual problems, communication, and sexual satisfaction. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 6(4): 277-283.

- Leclerc B, Bergeron S, Brassard A, Bélanger C, Steben M, et al. (2015) Attachment, sexual assertiveness, and sexual outcomes in women with provoked vestibulodynia and their partners: a mediation model. Arch Sex Behav 44(6): 1561-1572.

- Trudel G, Turgeon L, Piché L (2000) Marital sexual aspects of old age. Sexual Relationship Therapy 15(4): 381-406.

- Kaplan HS (1977) Hypoactive sexual desire. J Sex Marital Ther 3(1): 3-9.

- Schover L, Lopiccolo J (1982) Treatment effectiveness for dysfunctions of sexual desire. J Sex Marital Ther 8(3): 179-197.

- Beck JG, Barlow DH (1987) The effect of anxiety and attentional focus on sexual responding-II: cognitive and affective patterns in erectile dysfunction. Behavior research and therapy 24(1): 19-26.

- Heiman J, Rowland D (1983) Affective and physiological sexual response patterns: the effects of instruction on sexually functional and dysfunctional men. J Psychosom Res 27(2): 105-116.

- Meister AW, Carey MP (1991) Depressed affect and male sexual arousal. Arch Sex Behav 20(6): 541-554.

- Nobre PJ, Pinto-Gouveia J (2006b) Emotions during sexual activity: differences between sexually functional and dysfunctional men and women. Arch Sex Behav 35(4): 491-499.

- Nobre PJ, Pinto-Gouveia J (2008b) Cognitive and emotional predictors of female sexual dysfunctions: preliminary findings. J Sex Marital Ther 34(4): 325-342.

- Andersen B, Cyranowski JM (1994) Women’s sexual self-schema. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 67(6): 1079-1100.

- Beaber TE, Werner PD (2009) The relationship between anxiety and sexual functioning in lesbians and heterosexual women. Comparative Study 56(5): 639-654.

- Gerrior KG, Watt MC, Weaver AD, Gallagher CE (2015) The role of anxiety sensitivity in the sexual functioning of women. Sexual and Relationship Therapy 30(3): 351-363.

- Purdon C, Holdaway L (2006) Non-erotic thoughts: content and relation to sexual functioning and sexual satisfaction. J Sex Res 43(2): 154-162.

- Purdon C, Watson C (2011) Non-erotic thoughts and sexual functioning. Arch Sex Behav 40(5): 891-902.

- Calogero RM, Thompson JK (2009) Potential implications of the objectification of women’s bodies for women’s sexual satisfaction. Body Image 6(2): 145-148.

- Faith MS, Schare ML (1993) The role of body image in sexually avoidant behavior. Arch sex behav 22(4): 345-356.

- Steer A, Tiggemann M (2008) The role of self-objectification in women’s sexual functioning. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 27(3): 205-225.

- Vencil J, Tebbe EA, Garros S (2015) It’s not the size of the boat or the motion of the ocean: the role of self-objectification, appearance anxiety, and depression in female sexual functioning. Psychology of Women Quarterly 39(4): 471-483.

- Fine M (1988) Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: the missing discourse of desire. Harvard Educational Review 58(1): 29-53.

- Tolman DL (2002) Dilemmas of Desire: Teenage Girls Talk about Sexuality. MA: Harvard University Press, Cambridge.

- Higgins JA, Trussell J, Moore NB, Davidson JK (2010) Virginity lost, satisfaction gained? Physiological and psychological sexual satisfaction at heterosexual debut. J Sex Res 47(4): 384-394.

- Higgins JA, Mullinax M, Trussell J, Davidson JK, Moore NB, et al. (2011) Sexual satisfaction and sexual health among university students in the United States. Am J Public Health 101(9): 1643-1654.

- Moore NB, Davidson JK (1997) Guilt about first intercourse: an antecedent of sexual dissatisfaction among college women. J Sex Marital Ther 23(1): 29-46.

- Rosen R, Brown C, Heiman J, Leiblum S, Meston C, et al. (2000) The Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI): a multidimensional self-report instrument for the assessment of female sexual function. J Sex Marital Ther 26(2): 191-208.

- Baser RE, Li Y, Carter J (2012) Psychometric validation of the female sexual function index (FSFI) in cancer survivor. Cancer 188(18): 4606-4618.

- Giraldi A, Rellini A, Pfaus JG, Bitzer J, Laan E, et al. (2011) Questionnaires for assessment of female sexual dysfunction: A review and proposal for a standardized screener. J Sex Med 8(10): 2681-2706.

- Giuliano F (2013) Les questionnaires recommandés en médecine sexuelle. Progrès En Urologie 23(9): 811-821.