Future Directions: Analyzing Health Disparities Related to Maternal Hypertensive Disorders

Margaret Harris, Colette Henke, Mary Hearst and Katherine Campbell*

St. Catherine University, USA

Submission:August 23, 2019;Published:August 27, 2019

*Corresponding author: Katherine Campbell, St. Catherine University, USA

How to cite this article:Margaret Harris, Colette Henke, Mary Hearst and Katherine Campbell. Future Directions: Analyzing Health Disparities Related 002 to Maternal Hypertensive Disorders. J Gynecol Women’s Health. 2019: 16(2): 555934. DOI: 10.19080/JGWH.2019.16.555934

Abstract

Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy complicate up to 10% of pregnancies worldwide, constituting one of the most significant causes of maternal morbidity and mortality. Hypertensive disorders, specifically gestational hypertension, chronic hypertension, and preeclampsia throughout pregnancy, are contributors to the top causes of maternal mortality in the United States. Diagnosis of hypertensive disorders throughout pregnancy is challenging, with many disorders often remaining unrecognized or poorly managed during and after pregnancy. Moreover, research has identified a strong link between the prevalence of maternal hypertensive disorders and racial and ethnic disparities. Factors that influence the prevalence of maternal hypertensive disorders among racially and ethnically diverse women include maternal age, level of education, United States-born status, nonmetropolitan residence, pre-pregnancy obesity, excess weight gain during pregnancy, and gestational diabetes. Examination of the factors that increase the risk for maternal hypertensive disorders along with the current interventions utilized to manage hypertensive disorders, will assist in the identification of gaps in prevention and treatment strategies. Specific focus will be placed on disparities among racially and ethnically diverse women that increase risk for maternal hypertensive disorders. This review will serve to promote the development of interventions and strategies that better address and prevent hypertensive disorders throughout a pregnant woman’s continuum of care

Keywords: Maternal hypertensive disorders; Diagnosis; Risk factors; Ethnicity; Race; Disparity; Interventions

Abbreviations: ACOG: American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; AIANs: American Indian/Alaska Native women; BP: Blood Pressure; mmHg: Millimeters of Mercury; QI: Quality Improvement; WHO: The World Health Organization

Introduction

The World Health Organization WHO [1] defined maternal mortality as the death of a pregnant woman, regardless of the duration of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or exacerbated by the pregnancy, but not from accidental causes. Since the Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System was implemented, the number of reported maternal deaths in the United States as determined by the WHO’s definition, increased steadily from 7.2 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1987 to 18.0 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2014 [2]. This data presents a significant increase in maternal mortality rates in the United States and demands further investigation of underlying risks across diverse populations. While this documented rise in maternal mortality may be due in part to more rigorous and compelling reporting systems, it is critical that greater focus must be placed on developing innovative and individualized interventions and strategies to decrease the risk of maternal mortality among all populations.

Maternal mortality can be the result of a multitude of factors. Hypertensive disorders alone account for over a third of maternal deaths and contribute, in conjunction with other medical conditions, to half of all maternal deaths [3]. While not the focus of this mini review, studies have also identified an increase in chronic comorbid conditions during pregnancy as well, regardless of whether a hypertensive disorder is present or not [4]. Examples of comorbid conditions among pregnant women include diabetes and obesity, and when combined with a hypertensive disorder these conditions place women at an even higher risk for adverse outcomes during pregnancy [4]. While acknowledging that chronic comorbid conditions are a crucial aspect in the contribution of maternal mortality, this mini review seeks to focus specifically on hypertensive disorders and their contribution to maternal mortality.

Hypertensive disorders alone occur in approximately 5 to 11% of pregnant women [5,6]. Maternal hypertensive disorders include both chronic hypertension as well as gestational hypertension and preeclampsia [5,7,8]. The scope of this mini review will specifically focus on gestational hypertension. Ankumah and Sibai [9], defined gestational hypertension as systolic blood pressure (BP) of 140 millimeters of mercury (mmHg) and diastolic BP of 90mmHg documented either before pregnancy or before the 20th week of gestation on at least two separate occasions at least four hours apart. Ideally, a woman with a diagnosis of hypertension under this definition should be evaluated before conception with emphasis on determining the cause of hypertension and achieving reasonable BP control before pregnancy occurs [9]. However, obtaining and managing a diagnosis of hypertension may prove difficult if there is a delay in the initiation of obstetric care or if there is a lack of access to healthcare services in the woman’s geographic location, which illustrates that racial disparities in maternal mortality related to hypertensive disorders are persistent [6].

Data from Creanga et al. [3] illustrated that African American women contributed 14.6% of live births but 35.5% of maternal deaths; therefore, are at a 3.2 times higher risk of dying from a pregnancy-related complication than non-Hispanic white women. Furthermore, substantial racial and ethnic differences have also been noted in the prevalence of maternal hypertension: ranging from 2.2% for Chinese women and 2.9% for Vietnamese women to 8.9% for American Indian/Alaska Native women (AIANs) and 9.8% for African American women [8]. Thus, it is critical to better understand the intersection of maternal hypertensive disorders, racial and ethnic disparities, and their contribution to an increased risk of maternal mortality. Current practices related to prevention and treatment of hypertensive disorders will be examined, creating opportunity for the development of innovative approaches, both within and outside the clinical setting throughout the continuum of care.

Discussion

Search strategy

The exploration of the diagnosis and management of hypertensive disorders relating to increased risk of maternal morbidity and mortality required an integrative literature review. In particular, novel approaches that improve prevention and early detection of hypertensive disorders were sought. An electronic search was conducted using databases and online search engines, including CINAHL, MEDLINE, EBSCO, and PubMed. Authors searched these databases for relevant studies using a combination of keywords, including hypertensive disorders, pregnancy, outpatient, clinical setting, racial disparities, and innovative approaches. The search criteria included English language studies from 2010-2019. Article abstracts were then screened for relevance using peer appraisal. When filtering articles, the authors specifically targeted literature that focused on race and ethnicity, hypertensive disorders, the impact of race on maternal hypertension, outcomes related to the experience of care, current practices and interventions for hypertensive dis disorders, and women’s health. A final set of twenty-three studies were included for use in this mini review.

Risks, health disparities, and current interventions

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has published various guidelines for hypertensive disorders during pregnancy [10-12]. Specifically, ACOG [10] issued a report that included evidence-based recommendations for the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. These hypertensive disorders can be categorized as a) preeclampsia-eclampsia, b) chronic hypertension, c) chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia, and d) gestational hypertension [10].

The early prevention and detection of pregnancy-related hypertensive disorders are essential to monitor for new symptom development and to prevent complications [6]. Ankumah and Sibai [9] outlined an example of the importance of early detection and prevention of complications which determined that the results of a preliminary workup for hypertensive disorders in the clinic can aid the clinician in classifying hypertensive women into low-risk and high-risk categories. Although low-risk women tend to have excellent pregnancy outcomes, high-risk women are at increased risk for poor maternal and neonatal outcomes. Consequently, high-risk women should be considered for an increased frequency of outpatient BP monitoring and clinic visits [9,13].

Diagnosis of chronic hypertension at preconception or early in pregnancy is necessary as chronic hypertension is a recognized risk factor for preeclampsia, a hypertensive disorder with considerable risk for maternal mortality. ACOG’s [10] recommendations illustrated that complications might arise when a pregnant woman with previously, undiagnosed hypertension initially presents to the clinic in the second trimester of pregnancy with normal BP, after having experienced the pregnancy-associated physiologic decrease in BP. This woman will have been presumed to be normotensive upon assessment, and if her BP increased during the third trimester, she might be erroneously diagnosed with either gestational hypertension or preeclampsia [10]. This example highlights the need for intervention in the community setting, in the form of reproductive health education for women planning to become pregnant as well as an early clinical intervention for all women who are pregnant.

As evidenced by these examples, the current work-up used to diagnose hypertensive disorders during pregnancy is typically conducted in the clinic setting and is based on a combination of symptom evaluation (including chest pain, headache, and epigastric pain), lab values, blood pressure values, and history [5]. Notably, the risk for maternal mortality related to hypertensive disorders increases for the populations without access to clinical care during pregnancy [6]. However, when a woman does have access to a clinical workup and is diagnosed with a hypertensive disorder during pregnancy, the essential goals of management are to prevent severe hypertension and cerebral events from developing. Often, the prevention of such developments is accomplished with the use of antihypertensive medications [5]. However, studies have reported conflicting data related to the efficacy and timing of administering antihypertensive medication treatment for the management of maternal hypertensive disorders. For example, antihypertensive therapies have not been illustrated to reduce the incidence of superimposed preeclampsia [5,13,14].

Furthermore, as a result of the individual recommendations for the management of each type of hypertensive disorder, occasionally, the current treatment with antihypertensive medications is not indicated at all. Instead, for example, ACOG [10] and Folk [5] both recommended the use of home blood pressure monitoring along with increased surveillance in the form of more frequent clinic visits to assess lab values and fetal growth for women with a diagnosis of low-risk gestational hypertension. In addition to at-home blood pressure cuffs, digital weight scales, phone oximeters, and mobile applications are additional technological solutions currently being utilized as interventions to monitor for hypertensive disorders among pregnant women. Despite current use, further evidence is required to support the use of these technologies as effective management methods for hypertensive disorders during pregnancy [6].

In spite of the various interventions currently being used to treat hypertensive disorders, racial and ethnic disparities continue to contribute to maternal mortality [15-18]. The CDC [19] defines disparities in health as differences in the burden of disease or in opportunities to achieve optimal health. Gadson, et al. [20] explored the social determinants of racial and ethnic disparities as they relate to the utilization of prenatal care and subsequent maternal outcomes. Results from the study found that African American, Hispanic, and Native American women were at risk for late entry into clinical care, and African American women alone were at significantly higher risk for maternal mortality. Delay in seeking prenatal care was further demonstrated in data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s [2] Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, which presented that African American and Hispanic women who die of pregnancy-related causes are more likely than white women to initiate prenatal care in the second and third trimesters. Factors that impact the utilization of clinical services during pregnancy, and subsequent health outcomes, include socioeconomic and cultural factors, accessibility of facilities, and discrepancies in quality care [2,20].

Alhusen, Bower, Epstein, and Sharps [21] examined factors that may influence delays in women seeking care. These factors included experiences of institutional racism in both accessing and receiving prenatal care as well as inflammatory markers of stress in the presence of health care providers [21]. Better knowledge of women’s views towards accessing clinical care throughout the continuum of pregnancy can assist in the development of strategies to eradicate these barriers and potentially re-imagine a care delivery model that serves pregnant women from all backgrounds. Importantly, further work is still necessary to meaningfully address these inequities.

Recommendations

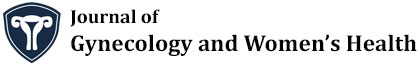

Through exploration of factors that increase risk for maternal hypertension, it can be declared that addressing hypertensive disorders in pregnancy requires early identification. Ideally identification of hypertensive disorders would occur before pregnancy. Then continuous, risk-appropriate clinical care and follow-up throughout the continuum of pregnancy could be implemented. This continuum of quality care is critical to improving maternal outcomes. To assist in the reduction of complications, there is a need for multifaceted interventions throughout both the intrapartum and postpartum period [3]. Exploration and utilization of primary, secondary, and tertiary interventions should occur prior to conception to reduce maternal mortality related to hypertensive disorders [3,22] (Figure 1). Furthermore, a priority should be placed on the development of interventions that are accessible to women located in both resource-rich and resource-poor settings during early pregnancy to address racial bias and discrimination in both the outpatient and clinic setting [14,20]. Understanding the origins of these biases is an emerging public health priority in light of the increasing rates of maternal mortality [18].

Along with clinical and outpatient recommendations, quality improvement (QI) recommendations need to be considered. Hernandez et al. [23] identified contributing factors and missed opportunities relating to maternal mortality events in Florida and translated the findings into QI recommendations aimed at reducing maternal mortality. The QI recommendations included 1. timely diagnosis and evidence-based treatment of specific clinical conditions including hypertensive disorders and 2. recognition and response to clinical triggers that show a change in clinical status [23].

Conclusion

Through this review, it can be determined that healthcare organizations should acknowledge that maternal mortality reflects maternal health among a population and may indicate gaps in care protocols in the clinical setting. In addition to implementing the clinical QI recommendations identified by Hernandez et al. [23], it will be critical to develop and investigate at-home and community-based interventions that address earlier disparities in access to care. Overwhelmingly, the literature in this mini review supports recommendations for further discussion and evaluation of the risks of hypertensive disorders that contribute to maternal mortality, while taking into consideration social determinants that may be influenced by diversity, and the need for quality improvement interventions in and out of the clinic and throughout a woman’s pregnancy

References

- World Health Organization (2019) Maternal mortality ratio (per 100 000 live births).

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC] (2014) Pregnancy-related mortality surveillance.

- Creanga A, Berg C, Syverson C, Seed K, Bruce FC, et al. (2015) Pregnancy-related mortality in the United States, 2006-2010. Obstet Gynecol 125(1): 5-12.

- Townsend R, O’Brien P, Kahlil A (2016) Current best practices in the management of hypertensive disorders in pregnancy. Integr Blood Press Control 9: 79-94.

- Folk D (2018) Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy: Overview and current recommendations. J Midwifery Womens Health 63(3): 289-300.

- Rivera-Romero O, Olmo A, Munoz R, Stiefel P, Miranda M, et al. (2018) Mobile health solutions for hypertensive disorders in pregnancy: Scoping literature review. JMIR Mhealth Uhealth 6(5): e130.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG] (2019) Preeclampsia and hypertension in Pregnancy: Resource overview.

- Graham W, Woodd S, Byass P, Filippi V, Gon G, et al. (2016) Diversity and divergence: The dynamic burden of poor maternal health. Lancet 388(10056): 2164-2175.

- Ankumah N, Sibai B (2016) Chronic hypertension in pregnancy: Diagnosis, management, and outcomes. Clin Obstet Gynecol 60(1): 206-114.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG] (2013) Hypertension in pregnancy. Report of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Task Force on Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 122(5): 1122-1131.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG] (2019a) ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 202: Gestational Hypertension and Preeclampsia. Obstet Gynecol 133(1): e1-25.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [ACOG] (2019b) ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 203: Chronic Hypertension in Pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol 133(1): e26-50.

- Magee L, Dadelszen P (2018) State-of-the-art diagnosis and treatment of hypertension in pregnancy. Mayo Clin Proc 93(11): 1664-1677.

- Ganapathy R, Grewal A, Castleman JS (2016) Remote monitoring of blood pressure to reduce the risk of preeclampsia-related complications with innovative use of mobile technology. Pregnancy Hypertension 6(4): 263-265.

- Bryant A, Worjoloh A, Caughey A, Washington AE (2010) Racial/ethnic disparities in obstetric outcomes and care: Prevalence and determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol 202(4): 335-343.

- Creanga A, Bateman B, Kuklina E, Callaghan W (2014) Racial and ethnic disparities in severe maternal morbidity: A multistate analysis, 2008–2010. Am J Obstet Gynecol 210(5): 435.e1-8.

- Gray K, Wallace E, Nelson K, Reed S, Schiff M, et al. (2012) Population-based study of risk factors for severe maternal morbidity. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol 26(6): 506-514.

- Grobman W, Bailit J, Rice M, Wapner R, Reddy U, et al. (2015) Racial and ethnic disparities in maternal morbidity and obstetric care. Obstet Gynecol 125(6): 1460-1467.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC]. (2017) Health disparities.

- Gadson A, Akpovi E, Mehta P (2017) Exploring the social determinants of racial/ethnic disparities in prenatal care utilization and maternal outcome. Semin Perinatol 41(5): 308-317.

- Alhusen JL, Bower KM, Epstein E, Sharps P (2016) Racial discrimination and adverse birth outcomes: An integrative review. J Midwifery & Womens Health 61(6): 707-720.

- Denny C, Floyd R, Green P, Hayes D (2012) Racial and ethnic disparities in preconception risk factors and preconception care. J Womens Health 21(7): 720-729.

- Hernandez LE, Sappenfield WM, Harris K, Burch D, Hill WC, et al. (2017) Pregnancy-related deaths, Florida, 1999-2012: Opportunities to improve maternal outcomes. Matern Child Health J 22(2): 204-215.