The Experience of Pregnancy Discovery and Acceptance: A Descriptive Study Based on free Hierarchical Evocation by Associative Networks

Marie Greve-Bricheux1-3, Rebecca White-Schielke1-3, Annamaria Silvana de Rosa4, Elena Bocci4, Laurent Letrilliart1-3, Jean Iwaz 2,3,5,6 and René Ecochard2,3,5,6*

1Collège Universitaire de Médecine Générale, Université Lyon, France Université de Lyon

2Université de Lyon, France

3Université Lyon 1, Villeurbanne, France

4Sapienza Università di Roma, European/International Joint PhD in Social Representations and Communication, Italy

5Service de Biostatistique-Bioinformatique, Pôle Santé Publique, Hospices Civils de Lyon, France

6CNRS, UMR 5558, Laboratoire de Biométrie et Biologie Évolutive, Équipe Biostatistique-Santé, Villeurbanne, France

Submission: March 11, 2019;Published: March 20, 2019

*Corresponding author: René Ecochard, Service de Biostatistique-Bioinformatique 162 avenue Lacassagne, F-69424-Lyon Cedex, France

How to cite this article: Greve-Bricheux M, White-Schielke R, de Rosa AS, Bocci E, Letrilliart L, et al. The Experience of Pregnancy Discovery and Acceptance: A Descriptive Study Based on free Hierarchical Evocation by Associative Networks. 2019: 14(4): 555893. DOI: 10.19080/JGWH.2019.14.555893

Abstract

Women’s childbearing experiences vary with pregnancy intentional nature and outcome. An Associative Network study targeted 129 women pregnant >1 year ago and their experiences at pregnancy start and post-pregnancy. Word-associations formed 15 themes and 5 metathemes. The main pregnancy discovery themes were “Affect” (39%), “Relationships with others” (11%), and “Logistics” (7%). The main post-pregnancy themes were “Affect” (18%), “Relationship with the child” (13%), and “Personal progress” (12%). The overall polarity index was higher in intended vs. unintended pregnancies. Whatever pregnancy outcome, women expressed impressions of constructive experience. Discovering pregnancy and deciding about it led anyway to personal and social progress.

Keywords: Experience of pregnancy; Pregnancy discovery; Spontaneous miscarriage; Elective abortion; Unintended pregnancy

Introduction

The moment of pregnancy discovery is very important and unique but may be sometimes neglected vs. the moment of birth that women and close relatives often consider as the culmination of pregnancy on an emotional level. The physical, physiological, hormonal, and psychological changes of the start of pregnancy, together with the experiences of previous pregnancies, influence women feelings, relationships, and decisions [1]. At the start of pregnancy, many women are particularly sensitive to exchanges, especially with healthcare professionals. Actually, a lot of information needs to be imparted during the first consultation after pregnancy discovery. This varies according to the context within which pregnancy occurred and the intention to carry it to term or not. These circumstances may conceal a serious exploration of how women feel about discovering they are pregnant.

To date, few studies have reported on the experience of the first days of pregnancy. The literature has rather focused on the experience of the second and third trimesters of pregnancy [2,3], miscarriage (MC) [4], elective abortion (EA) [5], or particular maternal or fetal situations [6-9]. However, Hopkins, et al. [10] have shown that women begin to build up their idea of maternity well before they are pregnant. Thus, the first days are particularly important because women begin to confront their experience with the representation they formed earlier. Moreover, when a woman announces a pregnancy, she receives a flow of advice and socially-normalized narratives of various experiences that do not necessarily correspond to her personal experience, which may induce feelings of guilt and anxiety [11].

In addition, up to 25% of pregnancies might not have been intended [12,13]. According to some authors, this has negative consequences on the neonate’s health [14,15], or the mother’s health such as a higher risk of postpartum depression [16], which is further increased by an unfavorable social context or a negative experience of the delivery [17]. The relationship between the intentional nature of a pregnancy and the way it is experienced later seems to have been less explored than the relationships with various medical outcomes.

Women experiences are usually explored via questionnaires with predefined answers [3], or semi-structured interviews [7,18], whereas free answers offer access to the various stages of the thought process and the unique wealth of feelings. Within this context, hierarchical evocations allow free and unguided answers to the researcher’s questions [19]. The method was originally introduced in the study of social representations then used in the healthcare field [20]. It is based on the association of ideas, feelings, perceptions, evaluations, etc. It combines thematic and statistical analyses and allows calculating an “index of polarity” for each evoked semantic representation field.

We present here the results of a hierarchical evocation study of women experiences at the time of pregnancy discovery and post pregnancy. The aim was to describe these experiences first generally then according to the pregnancy intentional nature and outcome.

Methods

Study type, recruitment, and inclusion

This observational, retrospective, and multicentric study was carried out in women recruited from three French Départements: Rhône, Ardèche, and Drôme. The proposals to participate were made at the end of a consultation (general practitioner, midwife, family planning, or breastfeeding counselor) through mutual recruitment or notices posted in waiting rooms. The women had to be aged 18 to 49 years (inclusive). The maximum of 49 years was chosen to avoid the potential influence of menopause. The last pregnancy should have been started at least one year before to ensure that women had some hindsight of their experience. The study protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the group of Lyon teaching hospitals (Hospices Civils de Lyon).

Data collection

The interviews took place between October 2014 and April 2016 and were conducted by two physicians (MGB and RWS). The choice was made to interview each woman on her first or last pregnancy considering that the experiences may vary with the rank of the pregnancy. This was obtained using a randomization list. Each interview included the administration of a projective technique: the “associative network” [19], using two stimulus expressions. The first stimulus expression “The first days…” (Box 1) focused on the experience of discovering pregnancy. The second stimulus expression “Since then…” (Box 2) focused on the experience of post-pregnancy.

After each stimulus expression, each woman was invited to write freely words or expressions that came to her mind and join to each word or expression a number that reflects the order of its evocation. She had then to:

a) build networks by drawing lines between words or expressions

b) give a polarity to each word or expression; i.e., its association with a positive, negative, or neutral feeling

c) give a rank to each word or expression; i.e., its importance in her feelings [19].

The data collected as responses to the stimulus expressions “The first days” and “Since then” (i.e., the written words or expressions) had to be clustered into subthemes, then into themes, and then again into metathemes.

Each interview included also a questionnaire that collected sociodemographic data (date of birth, medical history, and professional activity) as well as data on the pregnancy under study and on other pregnancies. The following factors were specifically recorded:

a) the intentional nature of the pregnancy: intended or unintended (unplanned or unwanted)

b) the age and marital status at the time of the pregnancy (marriage, civil union, or else)

c) the outcome of the pregnancy (full-term live birth, MC, EA, therapeutic abortion).

Data analysis

The outcome criteria were the mean frequency of words or expressions and the mean polarity index. According to the Associative Network technique [19], the polarity index was defined as the number of positive words minus the number of negative words divided by the total number of words (the number of neutral words does not influence the index). This index ranges thus from -1 to +1 and shows the overall positive or negative tone of each theme. The outcome criteria were calculated:

a) for each subtheme and theme

b) according to the intentional nature of the pregnancy at each stimulus expression

c) according to the outcome of pregnancy at stimulus expression “Since then”.

The participants were described in terms of number of participants, number of pregnancies per woman, socioeconomic status, marital status, and intentional nature and outcome of the pregnancy under study. Pearson’s chi-squared tests were used to assess possible differences in pregnancy outcomes according to age, marital status, and pregnancy rank (univariate analysis). Then the relationships between these factors and pregnancy outcomes were studied in a multivariate analysis using a logistic regression. Next, the relationship between the intentional nature of the pregnancy under study and its outcome was expressed as an Odds Ratio (OR) with a profile likelihood confidence interval and the significance of the deviations tested using likelihood ratio tests.

Finally, the most frequently mentioned themes and the polarity indexes were compared using Pearson’s chi-squared tests and Wilcoxon-Mann-Whitney’s nonparametric tests, respectively. Comparisons were carried out according to the intentional nature of pregnancy with each stimulus expression. Comparisons were also made according to the outcome of pregnancy but only with stimulus expression “Since then”.

Result

Characteristics of the participants

Finally, 129 women were interviewed. They were aged 18 to 49 years at the time of the interview and 14 to 42 years at the time of pregnancy. These women had had 1 to 8 pregnancies (carried to term or not), which corresponds to an average of 2.41 pregnancies per woman and a fertility rate of 1.68. The participants included all socioeconomic statuses: 40 had intermediate occupations (31%), 39 were employees or manual workers (30%), 28 were managers or had high-status professions (22%), 6 were craftswomen, shopworkers, or selfemployed workers (5%), 3 were agricultural workers (2%), and 13 women (10%) had no professional activity at the time of the interview.

The 129 women reported on 311 pregnancies of whom 19 (6%) were achieved via medically assisted procreation and five were twin pregnancies. The pregnancies were intended in 246 cases (79%). Concerning the marital status at the time of pregnancy, 125 pregnancies occurred in marriage, 38 in civil union (which totals 52% -- 163 out of 311 -- of pregnancies that occurred in stable relationships), 127 in cohabitation, 18 in singlehood, and 3 in divorce.

Values are number (% of total) - *Pearson’s chi-squared test - † Number and percentage over 257 observations.

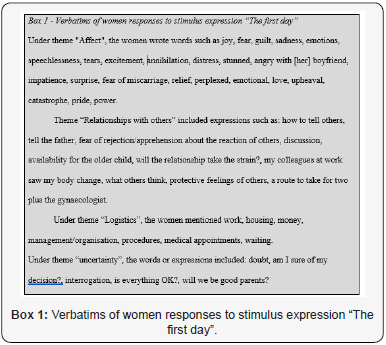

Pregnancy outcomes

Of the 311 pregnancies, 218 (70%) were carried to term, whereas 50 (16%) ended in MC, 39 (13%) in EA, and 4 (1%) in therapeutic abortion. Among the 129 pregnancies that were focuses of the evocations, 82 (64%) were carried to term, whereas 13 (10%) ended in MC, 31 (24%) in EA, and 3 (2%) in therapeutic abortion (Figure 1). Table 1 shows the characteristics linked with the 257 pregnancies that were carried to term or ended in an EA. EA was significantly more frequent among young women having a non-committed relationship and concerned mainly the first pregnancy. In the logistic analysis, an age under 25 (OR 4.2; 95% CI: 2.0-8.7) and non-commitment were associated with increased frequency of EAs (OR=4.2; 95% CI: 2.0-8.7 and OR= 2.1; 95% CI: 1-4.7, respectively). In the analysis of the relationship between the intention to become pregnant and pregnancy outcome, 96% of intended pregnancies (191/199) were carried to term vs. only 43% of the unintended pregnancies (25/58); i.e., the OR for continuing pregnancy when intended vs. unintended was 31 (95% CI: 13-71).

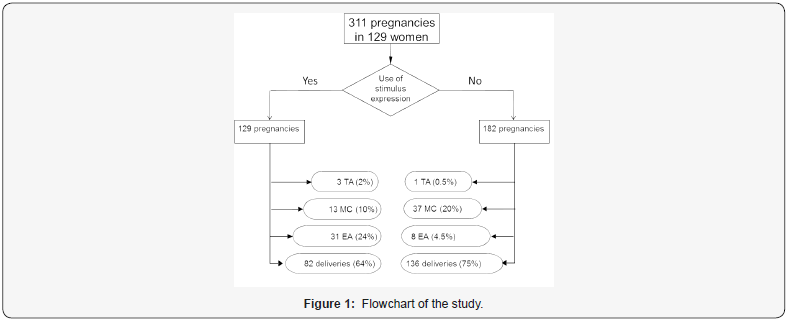

Word and expression clustering

The words or expressions written in response to stimulus expressions “The first days” and “Since then” could be clustered into 70 subthemes, 15 themes, and 5 metathemes. This hierarchy is shown in Figure 2. The “Medical” metatheme concerned the physical signs of pregnancy, its medical aspects, lifestyle, fertility as well as the stages of pregnancy (diagnosis, childbirth, breastfeeding, etc.). The “Contextual” and “Emotional” metathemes had only one theme each; these were, respectively, the logistics of going through with the pregnancy and all the affects related to this period of life. The “Relational” metatheme had one theme per type of relationship: the child, the family members, the friends and colleagues, and various aspects of parenthood. The “Cognitive” metatheme could include four themes: desire of pregnancy, personal progress brought about by pregnancy, uncertainties, and projections for the future.

Representational fields evoked by stimulus expression “The first days”

The most frequently mentioned themes were:

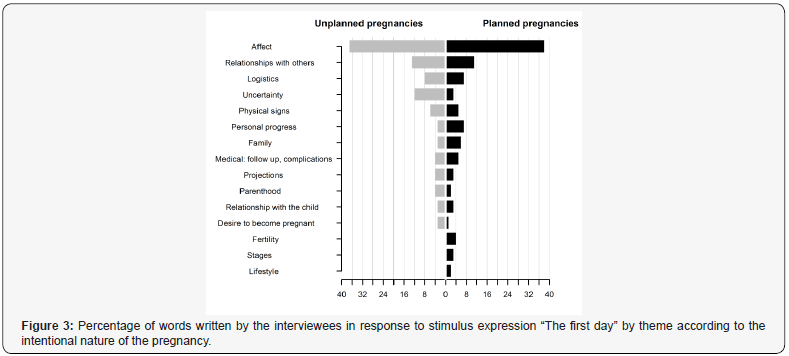

a) the “Affect” (406 out of 1084 words; i.e., 37%, with subthemes joy, anxiety, and surprise)

b) the “Relationships with others” (123 words, 11%) with main subthemes announcement of pregnancy and relationship with the father of the child

c) “Logistics” (79 words, 7%,) with subthemes finances, time management, logistical organisation. The average number of words written per woman was 8.2 words. When this was examined according to the intentional nature of the pregnancy, themes “Affect” and “Relationships with others” remained the first mentioned regardless of the outcome of the pregnancy (Figure 3). Theme “Logistics” (n=54, 7%) was the third most often mentioned in intended pregnancies, whereas it was “uncertainty” (n=40, 12%) that held the third place in unintended pregnancies with subthemes such as questioning and ambivalence. The polarity index that ranges from -1 to +1 was shifted by +0.26 units in intended vs. unintended pregnancies (95% CI: 0.12-0.42).

Representational fields evoked by stimulus expression “Since then”

During this second evocative setting, the women spoke about “affect” (229 out of 1,250 words collected; i.e., 18%), “Relationship with the child” (164 words, 13%), and “Personal progress” (156 words, 12%, with subthemes “growth, maturity”, “quest for meaning”, “acceptance of having had an abortion”). Comparing theme frequencies according to the intentional nature of the pregnancy, the notion of “Personal progress” appeared first (71 times, 22%) in unintended pregnancies, then “affect” (57 times, 18%), then “Relationship with the child” (36 times, 11%), whereas in intended pregnancies, “Affect” was mentioned first (172 times, 18%), before “Relationship with the child” (128 times, 14%) and “Family” (96 times, 10%).

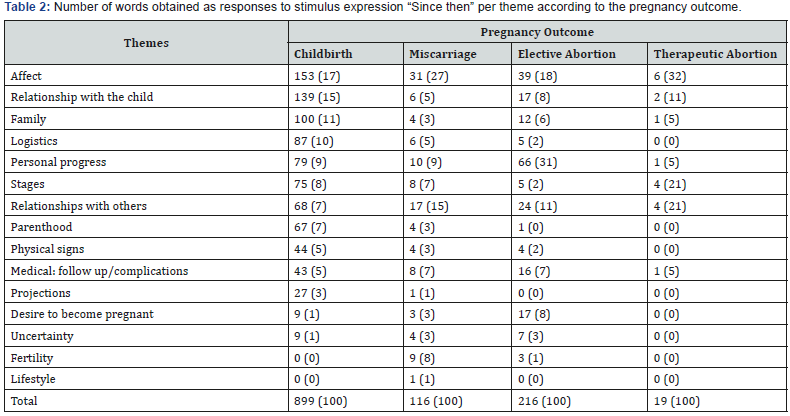

The mean polarity index over all themes was not significantly different between intended and unintended pregnancies. In response to stimulus expression “Since then”, the women wrote fewer words when they had had an EA or a MC (10.1, 7.9, and 6.6 terms on average in case of childbirth, MC, and EA, respectively). However, this difference was not statistically significant (p=0.3). Comparing theme frequencies according to the outcome of pregnancy, themes “Affect” (153 times, 17%), “Relationship with the child” (139 times, 15%) and “Family” (100 times, 11%) were the most frequent in pregnancies carried to term (Table 2). In MCs and EAs, three main themes were the most frequently mentioned but not in the same order: “Personal progress” (10 times, 9% in MC vs. 66 times, 31% in EA), “affect” (31 times, 27% in MC vs. 39 times, 18% in EA), and “Relationship with others” (17 times, 15% in MC vs. 24 times, 11% in EA).

Values are number (% of total).

In women who had had a MC, theme “Fertility” (9 times, 8%) appeared in the fourth position, whereas it was not mentioned by women who carried pregnancies to term. The mean polarity index over all themes collected in response to stimulus expression “Since then” was not significantly different according to the outcome of the pregnancy.

Discussion

In this study of women responses to two stimulus expressions, women asked to recall their thoughts about discovering they were pregnant mentioned most often themes “Affect”, “Relationships with others”, and “Logistics” when pregnancy was intended, whereas, when the pregnancy was unintended, the women mentioned more frequently “Uncertainty” than “Logistics” and the polarity index was significantly higher when the pregnancies were intended. Late after a pregnancy, the most often mentioned themes were “Affect” then “Relationship with the child”. Comparing theme frequencies according to the intentional nature of the pregnancy showed that theme “Family” appeared in the third place in intended pregnancies, whereas it was “Personal progress” that appeared in the third place in unintended pregnancies. Comparing theme frequencies according to the outcome of pregnancy showed that themes “Affect”, “Relationship with the child”, then “Family” appeared first in women with pregnancies carried to term but that themes “Personal progress”, “Affect”, and “Relationships with others” appeared first in women with pregnancies that ended in MC or EA. These results illustrate the ways women feelings differ according to the intentional nature of pregnancy and the outcome of pregnancy.

One advantage of the use of Associative Networks for this research is that women are able to express themselves freely because the method was developed to reduce or even eliminate the influence of an investigator or that of “social desirability” of the answers. This is very important in an area where social standards are constantly present. For example, in 2012, Menuel mentioned an “injunction to be happy” for pregnant women as well as an “injunction to remain silent” regarding the inconveniences of pregnancy.

Another advantage is the interesting scale of the study (129 women) that involved a wide socioeconomic diversity and a glowing wealth of feelings. Although common themes were obviously found, each interview was unique regarding the words used to talk about the start of pregnancy or the post-pregnancy period. A third advantage is data saturation in pregnancies carried to term. Indeed, the geographical distribution of the women (rural, semi-rural, and urban) allowed access to populations of very different socioeconomic levels.

One limitation of the study is that nearly one third of the women volunteered to participate after reading a flyer in a medical or paramedical waiting room or after sharing information with other participants. This could have led to a selection bias by increasing the proportion of women who had particular experiences. For example, here, 6% of the pregnancies resulted from MAP techniques vs. only 3% in the general population [21]. Besides, women who had had an EA were more difficult to recruit than others (refusal to participate or missing appointment); this led to a lack of data saturation in this population. Furthermore, in choosing the first or last pregnancy, we could not access all contexts. Finally, the responses to stimulus expression “The first days” concerned experiences lived a few but sometimes up to 18 years ago. The time elapsed since the pregnancy under study could have toned down some feelings but one aim of the study was collecting feelings after a settle down over time.

Some data concerning pregnancy outcomes are roughly comparable to those of other French or European reports from the same period: a 1.68 fertility rate vs. 2.01 (Eurostat data), 20% of unintended pregnancies vs. 25% [12,22], a 16% rate of MCs vs. 20% [23], 59% of abortions in women <25 years of whom 38% in primiparae vs. 20-24% [24] of whom 42.8% in primiparea [25]. However, the 13% rate of EA found here was reached through consistent recruitment effort and cannot be compared with other rates from the literature (e.g., 26.4 EAs per 100 live births in 2011 [25]).

In a study by the French IPSOS on pregnancies carried to term, pregnancy is first a happy event and then a source of anxiety (97% and 89% of women, respectively) [26]. In the present study, the mean rank of “joy” was 3.5 (mentioned 115 times) and that of “stress” 4.2 (mentioned 86 times) [2]. In another study performed in 2004, Courtial and Le Dreff made a distinction between two groups: “women without apparent problems” and “fragile women” [27]. In the first group, the authors found narratives organized around “joy”, “the importance for the husband”, and “the construction of the relationship”. These authors also reported on “proof”, developed as “proof of oneself, of love, of fertility”; in short, “proof of life”. These themes were present in our verbatims under “fulfilment”, “practical outworking of my love story”, “intensity of life”, “wonder at the miracle of life”, and “creative force”. In “fragile women”, “fear” was cited and associated with many aspects of pregnancy (particularly parturition). One important difference between the present study and that of Courtial and Le Dreff [27] is that the latter was carried out in primiparae.

Concerning the post-pregnancy period, the present study found once again themes already mentioned by Courtial and Le Dreff [27]. In the latter study, women “without apparent problems” mentioned “not being able to give themselves personally to their baby, associated with fear, suffocated by people around them” and “fragile” women felt “constraints”, “difficulty of being a mother” and “tiredness” (qualified as psychological tiredness because it was related to difficulties with the partner). These authors insisted on the difference between this tiredness and the physical fatigue mentioned by the women “without apparent problems” because the latter associated fatigue with joy.

Concerning the experience of MC, previous studies Séjourné et al. [4]; Stirtzinger, et al, [28] have reported the importance of themes “Fertility” and “Relationship with the partner” because MC strengthened or weakened the marriage or the partnership. Séjourné et al. [29] examined the issue of guilt after a MC and emphasized that MC could be felt and expressed in many different ways, which was also the case in the evocations we collected.

In the present study, it was interesting to note that the women who had had a MC or an EA mentioned “personal progress” significantly more often than others. This suggests that these events were experienced as sufferings (words used: “suffering”, “sacrifice”, “trauma”, “emptiness”) associated with a need to overcome the event and find meaning for it. Nevertheless, for some women, EAs had no effect on their lives. These women wrote, for example, “nothing, no trace”, “no consequence”, or “a closed subject”. The literature review performed by Bradshaw & Slade [29] found a 30% rate of anxiety one month after EA but did not report a higher percentage of anxiety among women who had had a MC or a pregnancy carried to term. This observation supports the hypothesis that EA may be experienced as a painful event but that women develop strategies to overcome this pain. In the present study, after an EA, the women talked about “confidence in life and its purpose”; some wrote: “I have integrated it into my history”, “this event helped me grow”, “I will not have another EA”. In women who carried pregnancy to term, “family” ranked third in frequency, whereas, in women who aborted, it was “Personal progress” that ranked third (the first two themes were identical in the two groups). This emphasizes the importance of the changes that these women experience in becoming mothers (be it for the first time or not).

The present study shows that the occurrence of pregnancy is a time that is particularly rich in emotions, feelings, and questions that may be sometimes contradictory. Healthcare professionals should thus be attentive to women’s life contexts, especially at announcing pregnancy and at prenatal check-ups. In fact, (re) discovering the diversity of women feelings moves healthcare professionals closer to women’s concerns and improves their dialogue. Also, the study highlights the importance of keeping in mind that each woman is unique and expresses her thoughts and feelings in a personal way; this prevents the interviewer from projecting general or personal views onto the women.

From a medical perspective, as nearly 25% of the women in the present study expressed feelings of fatigue, or even exhaustion, health professionals should remain attentive to this issue in the mothers at each medical visit.

From a psychological perspective, women who carry pregnancy to term speak generally about a constructive life experience (couple, parent-child, and family relationships) and women who had had MC or EA speak generally about personal progress and development of strategies to overcome pain and regain confidence in life. Finally, discovering a pregnancy and deciding about its outcome raise a variety of problems that receive various solutions but participate anyway to personal growth and better awareness of social responsibility.

Funding Details

This work was supported by personal funds.

Disclosure Statement

The authors have no financial interest or benefit from the direct applications of the research.

References

- Bydlowski M (2001) Le regard intérieur de la femme enceinte, transparence psychique et représentation de l’objet interne. Devenir 13(2) : 41-52.

- Études cliniques IPSOS (2011) Le vécu de la grossesse [The experience of pregnancy]. Les dossiers de l’obstétrique 402: 6-12.

- Demarest EM (2010) Un corps en métamorphose: comment le vivent les femmes ? Etude prospective auprès de 134 primipares au 3ème trimestre de grossesse [Body in metamorphosis: how do women feel about it? Prospective study of 134 primiparae during the third trimester of pregnancy]. (Midwifery dissertation). Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Rouen, France.

- Séjourné N, Callahan S, Chabrol H (2009) La fausse couche : une expérience difficile et singulière [Miscarriage: a painful and singular experience]. Devenir 21(3): 143-157.

- Broen AN, Moum T, Bödtker AS, Ekeberg O (2005) Reasons for induced abortion and their relation to women’s emotional distress: a prospective, two-year follow-up study. General Hospital Psychiatry 27(1) : 36-43.

- Guillou J, Séjourné N, Chabrol H (2009) Appréhension et vécu d’une grossesse obtenue après un don d’ovocyte anonyme [Pregnancy following anonymous oocyte donation: Experience and feelings]. Gynécologie, obstétrique et fertilité 37(5) : 410-414.

- Hemmerter C (2015) Le vécu de grossesse chez les femmes transplantées rénales [The experience of pregnancy in renal transplant women]. (Midwifery dissertation). Ecole de Sages-Femmes de Strasbourg, France.

- Wendland J (2007) Le vécu psychologique de la grossesse gémellaire. Du désir d’enfant à la relation mère-foetus [The psychological experience of twin pregancy: Examining the Desire for Twins to the Mother-Fetus Relation]. Enfances & Psy 34(1) : 10-25.

- Weyl B (1984) Le vécu psychologique de la grossesse et de l’accouchement chez les mineures [Psychological experience of pregnancy and childbirth in minors]. Contraception fertilité sexualité 12(3): 507-511.

- Hopkins J, Clarke D, Cross W (2014) Inside stories: Maternal representations of first time mothers from pre-pregnancy to early pregnancy. Women Birth 27(1): 26-30.

- Menuel J (2012) Devenir enceinte. Socialisation et normalisation pendant la grossesse : Processus, réceptions, effets [Becoming pregnant. Socialisation and normalisation during pregnancy: process, receipt, effects]. Dossier d’études n°148, France.

- Declercq ER, Sakala C, Corry MP, Applebaum S (2007) Listening to mothers II, Report of the Second National US Survey of Women’s Childbearing Experiences: Conducted January-February 2006 for Childbirth Connection by Harris Interactive(R) in partnership with Lamaze International. J Perinat Educ16(4): 9-14.

- Oulman E, Kim TH, Yunis K, Tamim H (2015) Prevalence and predictors of unintended pregnancy among women: an analysis of the Canadian Maternity experience. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 15: 260.

- Angelo D, Gilbert DV, Rochat BC, Santelli RW, Herold JS, et al. (2004) Differences between mistimed and unwanted pregnancies among women who have live births. Perspect Sex Reprod Health 36(5): 192- 197.

- Han JY, Nava-Ocampo AA, Koren G (2005) Unintended pregnancies and exposure to potential human teratogens. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 73(4): 245-248.

- Mercier RJ, Garrett J, Thorp J, Siega-Riz AM (2013) Pregnancy intention and postpartum depression: secondary data analysis from a prospective cohort. BJOG 120(9): 1116-1122.

- Tani F, Castagna V (2017) Maternal social support, quality of birth experience, and post-partum depression in primiparous women. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 30(6): 689-692.

- Séjourné N, Callahan S, Chabrol H (2011) Avortement spontané et culpabilité: une étude qualitative [Miscarriage and feelings of guilt: a qualitative study]. Journal de gynécologie, obstétrique et biologie de la reproduction 40(5): 430-436.

- Rosa DAS (2005) Le réseau d’associations. In: JC Abric (Ed.), Méthodes d’étude des représentations sociales. Ramonville-Saint-Agne, France, pp. 81-117.

- Sardy R, Ecochard R, Lasserre E, Dubois JP, Floret D, et al. (2012) Représentations sociales de la vaccination chez les patients et les médecins généralistes : une étude basée sur l’évocation hiérarchisée [Social representations of vaccination among patients and general practitioners: a study based on hierarchized evocation]. Santé Publique 24(6) : 547-560.

- Agence de la biomédecine (2013) Activité d’Assistance Médicale à la Procréation 2012.

- Blondel B, Kermarrec M (2011) Enquête nationale périnatale 2010: Les naissances en 2010 et leur évolution depuis 2003.

- Love ER, Bhattacharya S, Smith NC, Bhattacharya S (2010) Effect of interpregnancy interval on outcomes of pregnancy after miscarriage: retrospective analysis of hospital episode statistics in Scotland. British Medical Journal 341: c3967.

- Ministère des Affaires sociales et de la Santé (2016) IVG: État des lieux et perspectives d’évolution du système d’information [VTP: Present situation and prospects of the information system].

- Mazuy M, Toulemon L, Baril E (2014) Le nombre d’IVG est stable, mais moins de femmes y ont recours [A steady number of induced abortions, but fewer women are concerned]. Population-F 69(3): 365-398.

- Collège National des Gynécologues et Obstétriciens Français (2009) 33° Journées Nationales. Paris-La Défense.

- Courtial JP, Le Dreff G (2004) Analyse de récits de femmes enceintes. Santé Publique 16(1): 105-121.

- Stirtzinger RM, Robinson GE, Stewart DE, Ralevski E (1999) Parameters of grieving in spontaneous abortion. Int J Psychiatry Med 29(2): 235- 249.

- Bradshaw Z, Slade P (2003) The effects of induced abortion on emotional experiences and relationships: A critical review of the literature. Clin Psychol Rev 23(7): 929-958.