Can Ratings of Contraceptive Methods Motivate Women to Engage in Family Planning and Birth Control? A Review

Kurt Kraetschmer*

Austrian-American Medical Research Institute Vienna, Austria

Submission: August 16, 2018; Published: September 07, 2018

*Corresponding author:Kurt Kraetschmer, Institution: Austrian-American Medical Research Institute Vienna, Agnesgasse 11, Austria, Tel:0043262228987 ; Fax: 0043262228987; EmailKurt.Kraetschmer@aon.at

How to cite this article:Kurt K. Can Ratings of Contraceptive Methods Motivate Women to Engage in Family Planning and Birth Control? A Review. J Gynecol Women’s Health. 2018: 11(4): 555817. DOI: 10.19080/JGWH.2018.11.555817

Abstract

Aims: The aim of the paper is to determine as to whether or not the various ratings and rankings propounded by the World Health Organization (WHO), government agencies, professional organizations, and research institutes are reliable instruments for women in search of a contraceptive method and for health care providers who assist women in these pursuits.

Method: To accomplish its goal, the review analyzes tables, surveys, and charts contained in the most frequently consulted sources of information, namely pertinent research articles as well as publications disseminated by government agencies. In order to accurately reflect present-day trends, the publications of the most influential agencies and institutions are selected among the vast number of available past and present sources.

Results: As a result of the systematic analysis of presently available rankings, shortcomings and inaccuracies are brought to light. They provide a rationale for the claim that revision of data is urgently needed.

Conclusion: In conclusion the study draws attention to the clinical reverberations of the topic and emphasizes the pivotal role of the health care provider who guides women in their search for the personally most suitable method of contraception.

Keywords: Contraception; Family planning; Birth control; Contraceptive efficacy

Abbrevations:WHO: World Health Organization; LARC: Long Acting Reversible Contraception; CTFT: Contraceptive Technology Failure Table; FDA: Food and Drug Administration; CIC: Combined Injectable Contraceptives; ECPs: Emergency Contraception Pills

Introduction

The importance of birth control, family planning, and contraception has been underscored in numerous studies. The World Health Organization (WHO) argues that the number of abortions could be reduced if appropriate contraceptive measures were taken: “An increase in the use of effective contraceptive methods results in reducing the incidence of abortion. Three out of four induced abortions could be eliminated if the need for family planning were fully met by expanding and improving family planning services and choices [1]. Studies in health statistics have highlighted the importance of contraceptive care. Assuming that the needs for contraception could be met, it is estimated that“ . . . 54 million unintended pregnancies, including 21 million unplanned births and 26 million abortions, would be averted annually [2]. Socio-economic studies have emphasized advantages for the taxpayer: “. . . every $1 spent on public funding for family planning saves taxpayers $3.74 in pregnancy-related costs [3]. Prevention of teenage pregnancy through Long Acting Reversible Contraception (LARC) has been investigated in evidence-based studies [4].

Contraception is not accepted by all women as a means to prevent unintended pregnancy. Unexpectedly, it is one of the most developed countries which has the highest rate of unintended pregnancy worldwide. “However, the most recent U.S. data still indicate that 45% of all pregnancies in the United States are unintended, as compared with 34% in Western Europe [5]. In fact, 38% of U.S. women in child-bearing age do not use contraception, according to statistical data from the year 2012 [6].

The reasons why a relatively large percentage of women in the U.S. and in other countries does not use contraception are a matter of debate, and frequently restricted access to contraception or unavailability of contraceptive care is inculpated. The present commentary argues that lack of accurate information is one of the reasons for women to remain undecided vis-à-vis contraception. The following discussion argues that presently available information on ratings and rankings of contraceptive methods does not enable women to make an intelligent choice, as stipulated by the ethical principle of informed consent. “The patient’s right of self-decision can be effectively exercised only if the patient possesses enough information to enable an intelligent choice [7].

Discussion

One of the first modern rankings appeared in 1982 and was entitled “Relative effectiveness of frequently used contraceptive methods“ [8]. Besides other shortcomings, this ranking did not distinguish between estimates for “common use“ and “correct and consistent use,“ as does the contemporary table of the WHO [9] or between “typical use“ and “perfect use“ as do several other tables, including the Contraceptive Technology Failure Table (CT Failure Table) [10]. This latter rating of contraceptive methods, published in a 2011 study on contraceptive efficacy, has been used as a source not only by the WHO but also by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

The CT Failure Table (CTFT)-A Reliable Source?

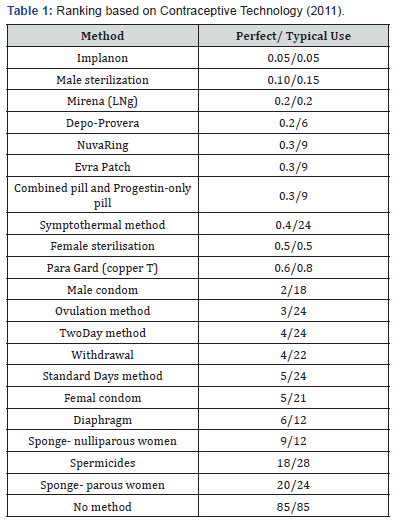

The CTFT rates the different methods according to estimates for women experiencing an unintended pregnancy during the first year of “typical use“ and the first year of “perfect use;“ an additional distinction is made between “first year of use“ and “continuing use at one year.“

According to this table, the LARC, ie, implants and intrauterine devices, are the most effective, especially the implant Implanon (precursor of Nexplanon) with a failure rate of 0.05 for both perfect and typical use. Among intrauterine contraceptives, Mirena (Levonorgestrel=LNg) with a perfect and typical use failure rate of 0.2 is superior to ParaGard (copper T) with a perfect use failure rate of 0.6 and a typical use failure rate of 0.8. Almost equally effective in perfect use are Depo-Provera (0.2 perfect use, 6 typical use), NuvaRing (0.3 perfect use, 9 typical use), Evra patch (0.3 perfect use, 9 typical use), as well as combined pill and progestin-only pill (0.3 perfect use, 9 typical use).

A ranking according to perfect use based on the CTFT yields the following table (Table 1). While this table provides reliable estimates, it fails to list Basal Body Temperature method, combined contraceptive patch and combined Contraceptive Vaginal Ring (CVR), monthly injectables or Combined Injectable Contraceptives (CIC), progestogen-only injectables, and calendar method (replaced by Standard Days).

An additional deficit is the use of obsolete data for the typical use estimates of several methods, including the fertility awareness-based methods. These data are not derived from genuine research but “. . . are take from the 1995 National Survey of Family Growth [10]. Despite these shortcomings the CTFT has been used as a source by other influential organizations such as the WHO and the FDA.

WHO and FDA Ratings

The WHO table of 2017 entitled “Effectiveness to prevent pregnancy“ lists the various methods without ranking them and distinguishes between “correct and consistent use“ and “common use.“ The table harmonizes with its source, the CTFT, except for the omission of the Ovulation (cervical mucus) method. This method deserves attention because its physiological foundation, ie, qualitative and quantitative changes in cervical mucus during the menstrual cycle, are not only fundamental parameters for contraception but are also essential in fertility research.

The omission of the ovulation method in the WHO table is a minor flaw compared to the incompleteness of a survey provided by the FDA in 2013, entitled “Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Approved Methods of Birth Control [11]. In this ranking, percentages are indicated for “number of women out of 100 who will NOT get pregnant,“ with the usual distinction between “perfect“ and “typical“ use.

According to this FDA survey, several methods achieve more than 99 percent for both perfect and typical use, namely: Sterilization Surgery for Women, Surgical Sterilization Implant for Women, Sterilization Surgery for Men, Implantable Rod, and IUD. These methods are considered equally effective in both perfect and typical use and are ranked higher than those whose typical use estimates are inferior to their perfect use estimates, namely:

1. Shot/Injection >99% perfect use (91% typical)

2. Oral Contraceptives (Combined pill: “The Pill”) >99% perfect use (91% typical)

3. Oral Contraceptives (Progestin-only: “The Pill”) >99% perfect use (91% typical)

4. Oral Contraceptives (Extended/Continuous use: “The Pill”) >99% perfect use (91% typical)

5. Patch >99 perfect use (91% typical)

6. Vaginal Contraceptive Ring >99 perfect use (91% typical).

Among the less effective methods, according to the FDA, are Male Condom, Diaphragm with Spermicide, Sponge with Spermicide, Cervical Cap with Spermicide, Female Condom, and Spermicide.

As can be seen, the FDA’s approach to ranking methods does not enable women to identify unambiguously the most effective methods. To wit, according to the FDA ranking, implantable rod and IUDs belong to the most effective methods (>99%). A more precise ranking, however, such as the one propounded by the CTFT [10], shows that implants and IUDs are by no means equally effective. In fact, implants (estimates of 0.05 for both perfect and typical use) are more effective than IUDs; the copper-containing IUD estimate is 0.8 for typical and 0.6 for perfect use and the levonorgestrel-containing IUD estimate is 0.2 for both typical and perfect use. Another weakness in the FDA survey is the omission of several methods, ie, the fertility awareness-based (periodic abstinence) methods. These methods are an integral part not only of the CTFT and the WHO table but also of most international publications.

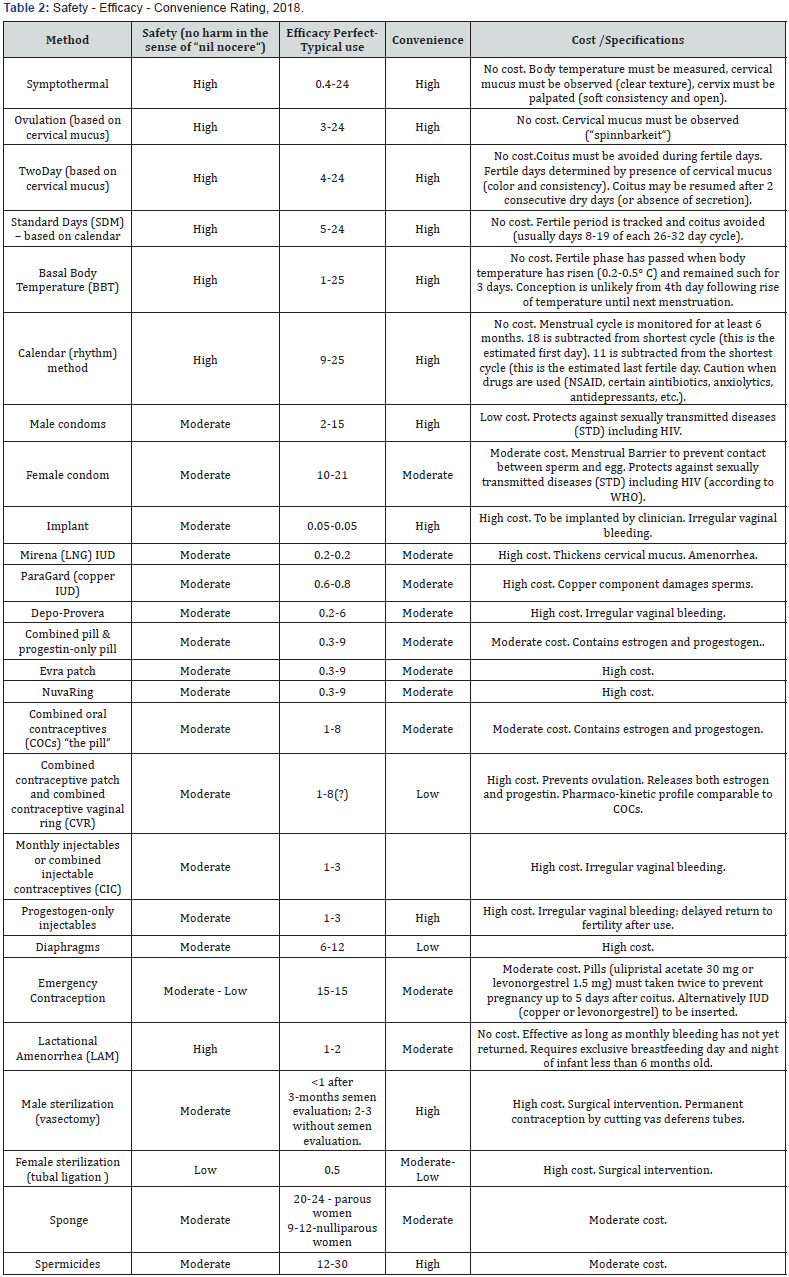

The Need for Comprehensive Rankings and Ratings

As shown above, an in-depth-analysis of presently available ratings and rankings reveals notable discrepancies. On the basis of a systematic comparison, the data presented by the CTFT [10]. Appear as the most accurate. However, even the CTFT does not completely satisfy the requirements of the principle of informed consent [7]. because it lacks vital information on safety. Yet, such information is indispensable for enabling women to make an intelligent choice, especially those women who are interested not only in efficacy but also in safety in the sense of no harm (“nil nocere“).

Regarding the concept of “safety“ one has to bear in mind various connotations of the term. Some women understand safety in the sense of protection against sexually transmitted diseases; they can heed the recommendations of the FDA: “Except for abstinence, latex condoms are the best protection against HIV/AIDS and other STIs [11]. For those women who interpret “safe“ as “truly effective,“ the ratings and rankings according to efficacy convey the relevant information. The majority of women understand “safe“ as meaning “not harmful,“ and for them several questions remain open. In fact, almost all influential rankings presently available focus on efficacy without paying particular attention to the aspect of safety. An exception is the WHO table which sporadically refers to adverse events. Such sporadic references might not suffice for those women and health care providers who desire comprehensive information on adverse events, risks, and complications. For them it will be insufficient to refer to death or a serious complication, as has been the case in a study on Emergency Contraception (EC): “No deaths or serious complications have been causally linked . . . “ to Emergency Contraception pills (ECPs) [12].

In order to meet the needs of those women whose understanding of safety encompasses more than death and serious complications, information on adverse events, risks, complications, and contraindications should be provided in future rankings. In addition, the aspect of convenience should be addressed, because convenience has an impact on compliance and insofar determines the perfect use estimate. A rating of contraceptive methods which takes into account the aspects of safety, convenience, and cost has been proposed recently (Table 2).

Such a rating might prove conducive to motivating women to engage in contraceptive pursuits, especially those with intolerance to hormones and devices or those who prefer to embrace a “natural“ method of contraception.

Conclusion

In view of the shortcomings in the ratings propounded by some of the most influential organisations, women are not adequately informed according to the principles of informed consent and nil nocere. It must be stipulated therefore that health care providers intensify efforts to assist women in their search for the personally most suitable method. Practitioners should take into account their patients’ interest in safety and pay heed to studies highlighting the impact of contraception on the quality of life.

References

- World Health Organization (2012) Safe and unsafe induced abortion. Global and regional levels in 2008, and trends during 1995–2008. Geneva, USA, p. 8.

- Sedgh G, Singh S, Hussain R (2014) Intended and Unintended Pregnancies Worldwide in 2012 and Recent Trends. Stud Fam Plann 45(3): 301-314.

- Cleland K, Peipert J, Westhoff C, Spear S, Trussell J, et al. (2011) Family planning as a cost-saving preventive health service. NEJM 364(18): e37

- Secura GM, Madden T, McNicholas C, et al. (2014) Provision of nocost, long-acting contraception and teenage pregnancy. N Engl J Med 371(14): 1316-1323.

- Curtis KM, Peipert JF (2017) Long-Acting Reversible Contraception. NEJM 376: 461-468.

- Jones J, Mosher W, Daniel K (2012) Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006-2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. Natl Health Stat Report 60: 1-25.

- (1992) Code of Ethics Current Opinions. Chicago, Illinois: American Medical Association. p.38.

- Vessey M, Lawless M, Yeates D (1982) Efficacy of different contraceptive methods. Lancet 1(8276): 841-842.

- www.who.int/mediacentre/re/factsheets/fs35/en

- Hatcher RA, Trussell J, Nelson AL, Cates W, Kowal D, et al. (2011) Contraceptive Technology. In: (Twentieth Revised Edn), Ardent Media, New York, USA, p. 906.

- ww. fad. g ov/ForCon sumer s/ByAudi en ce/ForWomen/ FreePublications/ucm313215.htm

- Trussell J, Raymond EG, Cleland K (2017) Emergency Contraception: A Last Chance to Prevent Unintended Pregnancy. Office of Population Research (OPR). Princeton University, USA.