Medicine's "Future": Pilot Data from a US Sample Shows Surgeons More Likely to Encourage Children to Pursue Medicine

Irene Dimitriadis MD1*, Beth J Plante MD2 and Kelly Pagidas MD 2*

1Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tufts Medical Center, USA

2Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Women and Infants' Center for Reproduction and Infertility,

Submission: March 01, 2018; Published: March 13, 2018

*Corresponding author: Irene Dimitriadis, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Tufts Medical Center, 55 Fruit Street, Yaw 10A Boston, MA, 02114, USA, Fax: 617-724-8882; Email: idimitriadis@partners.org

How to cite this article: Irene Dimitriadis M, Beth J P MD, Kelly P MD. Medicine's "Future": Pilot Data from a US Sample Shows Surgeons More Likely to Encourage Children to Pursue Medicine. J Gynecol Women's Health 2018; 9(1): 555751. DOI: 10.19080/JGWH.2018.09.555751

Abstract

Objective: A survey was conducted to ascertain knowledge on when doctors start having children and the likelihood of them encouraging their children to follow in their footsteps.

Methods

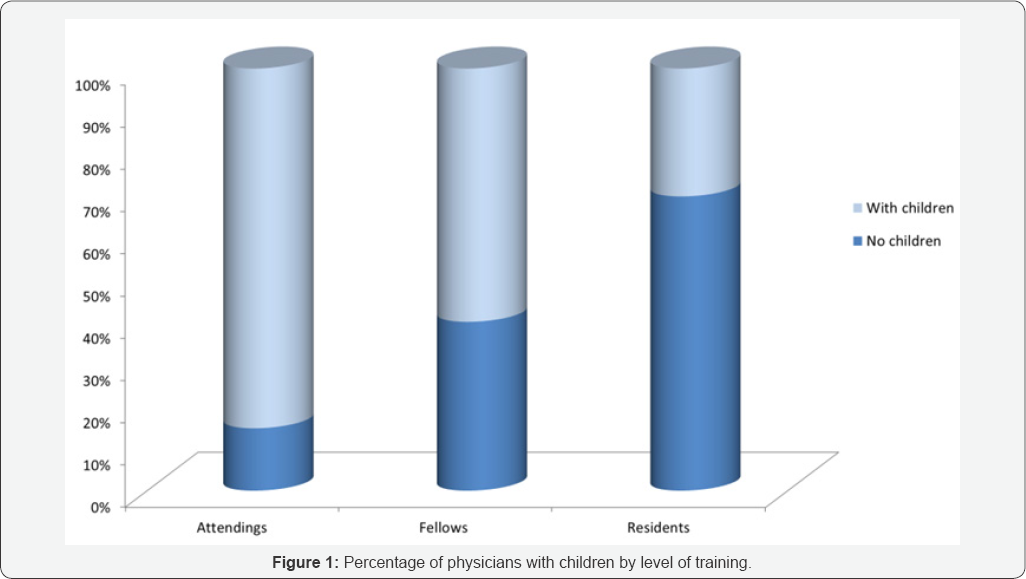

Design: Nationwide electronic survey (4/18/2013-7/18/2013), cross-sectional study

Setting: USA

Participants/Interventions: Physician recipients of a survey titled "Knowing what you know, would you encourage your children to become physicians?”, with active affiliations to ACGME accredited residency programs

Statistics: Chi-square test, used as appropriate. P<0.05, considered statistically significant. All data analysis was performed using SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina).

Results: Of 801 responses received, 85.2%, 60% and 30.3% of attendings, fellows and residents have children, respectively. Male residents are more likely to have children than females (42.2% vs 20.2%, p<0.0001). This gender difference vanished among attendings and fellows.

Across all training levels, surgical specialties are more likely to encourage their children to become physicians compared to non-surgical specialties (64.3% vs 45.5%; p<0.0001, respectively). Amongst physicians with sons and daughters, 21.2% of responders report a gender bias in regards to encouraging their children to become doctors, of which almost twice as many parents report that they would encourage their son compared to their daughter to pursue medicine (14% vs 7.2%, p=0.08).

Over 80% of physicians who would encourage their children to go into medicine would encourage them to pursue their specialty.

Conclusion: Surgical specialties are more likely to encourage their children to follow in their footsteps.

Keywords: Work-life balance; Medicine; Surgeons; Career satisfaction; Children; Female physicians

Introduction

A number of factors may influence physicians' career satisfaction and contribute to the common perception that physicians are becoming increasingly frustrated with the medical profession, including: increasing regulatory restrictions, medical liability, work-life balance, increasing healthcare costs, and decreased compensation. In March of 2012, an article published data from the Future of Health Care Survey that was conducted to decipher emerging industry challenges, which showed that nine out of ten physicians were found to be unwilling to recommend health care as a profession. This same study reported that over 40% of physician participants contemplated early retirement secondary to changes occurring within the American health care system. The results of this survey were characterized as very concerning by both the former president of the American Medical Association and member of The Doctors Company Board of Governors, Dr. Donald J. Palmisano and the chairman and chief executive officer of The Doctors Company, Dr. Richard E. Anderson [1].

As more Americans become insured and the population continues to age, the predicted shortage of the next generation of physicians may be perilous to the profession. With this survey our intention is to better understand physician attitudes practicing in the US regarding the likelihood of them encouraging their children, if and when they have them, to follow in their footsteps.

Materials and Methods

A survey titled "Knowing what you know, would you encourage your children to become physicians?” was sent via electronic mail to the Program Coordinators and/or Program Directors of graduate medical education programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The contact information was obtained through FREIDA, an online database of all graduate medical education programs in the United States that are accredited by the ACGME, provided at no charge by the American Medical Association. Recipients of the initial contact letter were asked to forward the survey and encourage all of their current residents, fellows and attendings to participate. The study was reviewed by the Institutional Review Board at Tufts Medical Center and received an exemption.

The 10-item questionnaire included demographic information and reasons for encouraging/discouraging children to pursue medicine. Individual characteristics of physician participants including gender, age, race/ethnicity and, specialty (grouped by nature of 5 categories: surgery, obstetrics and gynecology, internal medicine, pediatrics and other) were obtained.

Collaboration with the Tufts Clinical and Translational Science Institute was established for the statistical analysis of this project. All data analysis was performed using SAS v9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, North Carolina). Statistical testing was two-sided with alpha=0.05 (i.e. P values of 0.05 or less was considered statistically significant). The dataset consisted of categorical variables, thus the results are presented in terms of the number and proportion of physician participants who chose each option. Between-group differences were examined using chi square tests. The FREQ Procedure was utilized.

Results

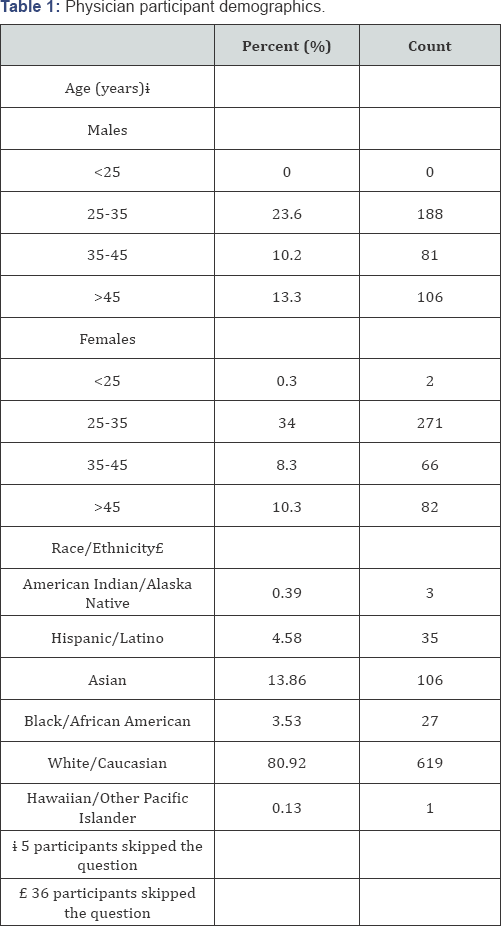

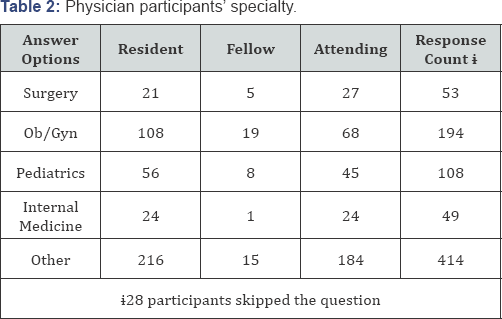

Eight hundred and one responses were received in a period of a little over 3 months (4/18-7/20/2013). Demographics of physician participants are summarized in Tables 1 & 2. Seven hundred and twenty-three physicians answered the question regarding their level of training at the time of the survey and whether they had children or not. 85.2%, 60% and 30.3% of the attendings, fellows and residents that responded have children, respectively (Figure 1).

Male residents were more likely to have children than females (42.2% vs 20.2%, p<0.0001). However, there were no gender differences noted among attendings (males versus females; 88.1% vs 82.2%, p=0.14) or fellows (males versus females; 69.2% vs 55.6%, p=0.41) with children.

Surgical specialties, including Ob/Gyns, were significantly more likely to encourage their children to become physicians compared to non-surgeons (64.3% vs 45.5% respectively, p<0.0001).

Surgical attendings were more likely to encourage their children to become physicians compared to medical specialties (71.4% vs 56.6%, p=0.02). This trend was noted for the surgical fellows as well but the numbers are very sparse. There was no difference in encouragement among surgical and medical residents. Of note, attending physicians of all specialties were significantly more likely to encourage their children to become physicians than physicians in other levels of training (58.6% vs 45.3%, p=0.0003). In particular, Ob/Gyns of all training levels were significantly more likely to encourage their children to become physicians compared to non-Ob/Gyns (66.3% vs 47.5% respectively, p<0.0001). The above findings persisted when only physicians with children were compared.

Of note, female physicians were slightly, but not significantly more likely to encourage their children to pursue the medical profession than male physicians (53.1% vs 49.1%, p=0.26). This trend became even smaller when only physicians who have children were analyzed (56% vs 54.1%, p=0.70).

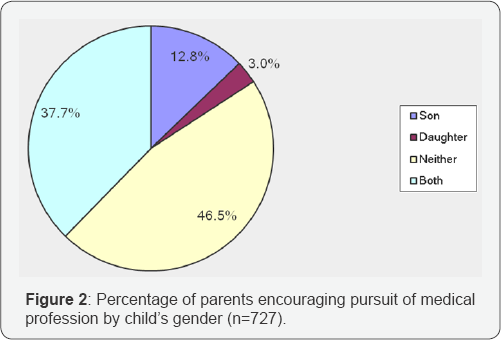

Of all physicians who took the survey, including those without children, 7.8% reported they would and 9.9% reported they perhaps would counsel their children differently about pursuing a medical career depending on their gender, whereas 82.3% answered that they would not alter their counseling depending on their children's genders. However, when they were asked later in the survey who they would be more likely to encourage to become a physician, 12.8% answered their son, 3% their daughter, 46.5% neither and 37.7% both (Figure 2). Amongst physicians with children of both genders, 39.4% would encourage both genders to become doctors and 39.4% would encourage neither. 21.2% of physician participants reported a gender bias in regards to encouraging their children to become doctors, of which almost twice as many parents reported that they would encourage their son compared to their daughter to pursue medicine (14% vs 7.2%, p=0.08).

The top two reasons for which physicians of all specialties encourage their children to go into medicine are: helping others (Ob/Gyns vs other surgical specialties vs medical specialties: 91.8%, 89.9%, and 86.7%, respectively) and financial stability (Ob/Gyns vs other surgical specialties vs medical specialties: 67.4%, 80.3%, and 59.5%, respectively). Other reasons of encouragement include prestige and a family history of doctors. Male physicians seem slightly more likely to encourage the profession for prestige than women (25.6% vs 20.4% respectively, chose prestige as one of the top 2 reasons for encouragement, p=0.08). No other differences appeared in the reasons for encouragement between genders.

On the contrary, the top two reasons physicians discourage their children to go into medicine are: work hours (Ob/Gyns vs other surgical specialties vs medical specialties: 70.5%, 62.3%, and 61.8%, respectively) and changes in the health care system (Ob/Gyns vs other surgical specialties vs medical specialties: 40.7%, 58.5%, and 54%, respectively). Other reasons physicians discourage their children from following in their footsteps include the feeling that technology has taken over medicine and that being a doctor does not carry the social significance it once did. They also worry about the debts left after medical school, physician compensation and the trend of practicing defensive medicine to avoid medical malpractice.

Of physicians who would encourage their children to go into medicine, 83.5% would encourage them to go into their specialty. Amongst doctors with children, surgical specialties (including Ob/Gyns) were found to support their own specialty similarly to non-surgeons (62.7% vs 60.4%, p=0.67). There was no significant difference between Ob/Gyns and other surgical specialties in encouraging their children to pursue their own specialty (59.6% vs 69.8%, p=0.25).

Discussion

The prevalence of burnout appears to be higher amongst physicians than among other professions in the US. The potential for burnout is an important predictor of choice of specialty and job satisfaction [2,3]. Many physicians report that the thought of quitting has crossed their minds [4]. Work hours, in particular, impact quality of life. In our study, work hours were the primary reason physicians would discourage their children from going into medicine.

Physician satisfaction and work-home conflicts have been shown to vary across career stages [5]. Work-life imbalance is reported to be a major contributor to burnout for both genders, but is more likely to affect female physicians [6] and may influence timing as physicians choose to start a family. In our study population, there was a significant difference at the resident level, as males were more likely to have had children in residency than females. This distinction, however, becomes balanced at more advanced career stages. There is also evidence that there are gender differences in time spent on parenting by physicians, as women are more likely to have spouses or domestic partners with full-time employment compared to men, and thus they spend over 8 hours per week more than their male counterparts on domestic activities [7]. The long-term impact of this domestic discrepancy between male and female physicians remains to be seen. In our study, female physicians tended to be more likely to encourage their children to pursue the medical profession but not significantly more so than male physicians.

Our study has significant strengths. This was a nationwide survey, including physicians from multiple specialties. The fact that ACGME accredited programs were contacted gave us the opportunity to reach out to all levels of training, including fellows and residents.

Our study is subject to limitations. Firstly, the analyses relied on self-reported data. A response rate was incalculable, as only the number of academic programs emailed are known. Thus, the number of physicians the survey was dispersed to by the program director or coordinator was unobtainable. Of note, the study included only physicians affiliated with an academic center. However, although private practices were not targeted, many of the programs have affiliations with private groups and we feel confident that this practice setting is well represented in our study. In addition, we did not use any type of incentives to encourage participation, including monetary incentives which are a proven technique to increase response rates [8].

Currently, there are other groups, including the Physicians Foundation, who are looking into the current state of the medical profession. In summary, our survey data shows that parental advice appears to vary according to specialty, as surgical specialties and Ob/Gyns, in particular, were more likely to encourage their children to follow in their footsteps than were all other physicians. Our data suggests that family-building is a priority for the majority of physicians and they are optimistic they can achieve work-life balance, although many delay parenthood until after residency. Given the above evidence, additional research should be conducted to evaluate the development of appropriate interventions that target the enhancement of these hidden feelings of optimism for the medical profession. This may defend the practice of medicine and return the "calling” to the profession which has been the hallmark for generations of physicians [1].

Conflict of Interest

All authors had full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. None of the authors have conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Nine Out of 10 Physicians Unwilling to Recommend Health Care As a Profession, Exacerbating Anticipated Physician Shortage

- Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps GJ, Russell T, Dyrbye L, et al. (2003) Burnout and career satisfaction among American Surgeons. Ann Surg 250(3): 463-471.

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, et al. (2012) Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med 172(18): 1377-1385.

- Danielle Ofri (2014) The epidemic of disillusioned doctors.

- Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, et al. (2013) Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc 88(12): 1358-1367.

- Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. (2011)Relationship between work-home conflicts and burnout among American surgeons: a comparison by sex. Arch Surg 46(2): 211-217.

- Shruti Jolly, Kent A Griffith, Rochelle DeCastro, Abigail Stewart, Peter Ubel, et al. (2014) Gender differences in time spent on parenting and domestic responsibilities by high-achieving young physician- researchers. Ann Intern Med 160(5): 344-353.

- Kellerman SE, Herold J (2001) Physician response to surveys: a review of the literature. Am J Prev Med 20(1): 61-67.