Narcissistic Personality Measures Discriminate Between Young Women With and Without Tattoos

Semion Kertzman1,2* , Alex Kagan3,4* , Michael Vainder5, Omer Hegedish1,6, Rina Lapidus7 and Abraham Weizman2,8

1Beer-Yaakov-Ness Ziona Mental Health Center, Forensic Psychiatry Division, Israel

2Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University, Israel

3Department of Neuro-Pathopsychology, LS Vygotsky Institute of Psychology, RSUH, Moscow, Russia

4The Program for Hermeneutics and Cultural Studies, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan Israel

5Environics Analytics, Canada

6Department of Psychology, University of Haifa, Israel

7Comparative Literature Department, Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel

8Research Unit, Geha Mental Health Center and Felsenstein Medical Research Center, Petah Tikva, Israel

Submission:January 29, 2021;Published:February 08, 2021

*Corresponding author:Semion Kertzman, kertzman@animascan.com Semion Kertzman and Alex Kagan contributed equally to this work

How to cite this article:Kertzman S, Kagan A, Vainder M, Hegedish O, Lapidus R, Weizman, A. Narcissistic Personality Measures Discriminate Between Young Women With and Without Tattoos. J Forensic Sci & Criminal Inves. 2021; 15(2): 555906 DOI:10.19080/JFSCI.2020.15.555906.

Abstract

Tattooing was proposed as a creative way for self-expression of the individuality. In the present study we assessed possible association between tattoos and narcissistic personality characteristics. To this end we have evaluated the interaction between narcissism and presence of tattoos in young women. Young women (aged 18-35 years) with (N=60) and without (N=60) tattoos completed the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI). Women with tattoos had received significantly higher scores of the Exhibition subscale of the NPI than those without tattoos. A logistic regression analysis demonstrated that high level of Exhibition subscale and low level of education are significant contributors to getting tattoo amongst young women.

Keywords: Tattoo; Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI); Exhibitionism

Background

Recently tattoos became an intriguing social phenomenon studied in several scientific disciplines such as criminology, sociology, ethnography, psychology, psychiatry, dermatology, and others. With time, tattoos became popular and entered the mainstream [1-6]. The tattoo industry continuously grows and the percentage of people getting tattoos has increased to such an extent that tattoos have become socially acceptable today [7,8]. This encoding of class on the body creates a physical standard of relatedness to higher social classes [9]. Permanent forms of body decoration such as tattoos are perceived as part of individual preferences related to the self- identity [10-14]. In a prospective study [15] showed that obtaining a first tattoo leads to a significant improvement in self-perception and immediate feeling of uniqueness. Thus, getting tattoos is frequently aimed at improving self-perception [16,17]. Despite increasing acceptance of tattoos, society has a long history of viewing the tattoos in context of deviant behavior with a social stigma [18-24]. Silver et al. [25]. found that among 13,101 adolescents’ tattoo acquisitions were predictive for prior negative self-appraisal. In a sample of 4,700 participants, self-reported experience of physical, sexual, and mental abuse and general emotional abandonment was significantly associated with tattoos, especially in the women [26]. Getting tattoo was associated with a high rate of self-injurious behavior [27], and suicidal attempts [28-30]. Dhossche et al. [31] analyzed data from 134 adolescent with lethal suicides and accidental deaths; the percentages of individuals with tattoos were 21% and 29%, respectively. A data analysis of 4,700 individuals who responded to a Web site (www. bmezine.com) for body modification, found that 36.6% of the males had suicidal ideation, and 19.5% had attempted suicide. The rates were significant higher for females: 40.8% and 33.3%, respectively [29]. Persons who have tattoos, show a wide range of externalizing problems such as tobacco, alcohol and drug use; a large number of sexual partners, unprotected sexual intercourse with strangers [30,32- 35]; academic difficulties, risky body health behavior [23,36- 38], “truancy” problems, pathological gambling, gang affiliatio [39] aggressive outbursts [27,40], a history of criminal arrest [30]. Jennings et al. [41] suggested that having tattoos can be considered as a developmental risk factor and an expression of personality traits. Psychological explanations for getting tattoo appear to remain unclear [14, 42].

Some researchers suggested that tattooing behavior may represent a marker of personality maladjustment [43-47], or complicated self-esteem [48]. Numerous studies linked tattoos with adolescent psychopathology [29,31,49] and adult antisocial behavior [30,35]. Swami et al. [50] suggested that between-group differences in the personality traits of persons with tattoos have been grossly overstated. Although there are some betweengroup differences in a range of personal traits, the effect sizes are small and negligible [38, 51, 52]. It is unclear whether tattoos serve as a sign of personality characteristics via self-expressive artwork. It is possible that tattoos express the need for external self-affirmation and self-esteem [53]. Persons with tattoo tend to rate themselves as more adventurous, creative, individualistic, and attractive than those without tattoos [32,54,55]. The goal of this study was to reinvestigate the differences between women with and without tattoos by focusing on narcissistic-related personality characteristics using psychometrics measures. A major shortcoming in similar previous studies is under-evaluation of the female (women) population [56]. In the present study, we evaluated in young women the relationship between having tattoo and narcissistic traits as measured by the Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI) [57]. Narcissism as measured by the NPI score is viewed as a continuum from adaptive forms to maladaptive narcissism [58,59]. It is of note that clinical psychopathological aspects of narcissism, such as personality disorders, were not included in this continuum [60]. Narcissism has been defined as a multifaceted construct consisting of seven components: autonomy, entitlement, exhibitionism, exploitation, self-sufficiency, superiority, and vanity [59,61,62]. It was reported that characteristics measured by the NPI correlated positively with the need for uniqueness [57]. For this reason, getting tattoo became with time more individualized and very personal [55]. However, the association between self-reported narcissism and having tattoos was not studied previously. The NPI measures were used to determine to what extent young, tattooed women exhibit more narcissistic characteristics compared to their non-tattooed counterparts. We hypothesized that: (1) Young tattooed women would have higher total score on the NPI than non-tattooed women; (2) Young tattooed women would report higher scores of the Exhibitionism subscale of the NPI than non-tattooed women.

Methods

As described previously [63,64], all women with and without tattoo were recruited through advertisements posted at the university, personal contacts and social networks (Facebook), to take part in a research project investigating decision making styles in tattooed women and those without tattoos. Recruitment took place in the Tel Aviv area from March 2012 to July 2012. Participants in both groups (research and control) were either employed, students or graduates and from a similar socioeconomic background. The participation in the study was voluntary, without payment. Compensation for participating in the study was a free of charge consultation about their inhibition capacity and professional advice regarding their neurocognitive and personality assessments. The study was approved by the Bar-Ilan University Review Board (Ramat Gan, Israel), and was conducted through individual sessions with an explanation regarding the research aims and with the subject’s signing a consent form. The duration of an individual session was up to an hour and half, with the entire research process taking place over a period of five months. Sixty young women with tattoo, aged 18 to 35 years old (M=28.4, SD=5.95) were included in the study. Fifty eight percent of the tattooed women had more than one tattoo. All the participants were employed or students with education level: high school diploma or lower – 46.7%, first university degree – 25%, second university degree– 23.3%, and philosophy degree – 5%. We analyzed only women in order to avoid gender differences on the NPI scales. Previously, it was found that men tended to be more narcissistic than women were, and this feature was not explained by measurement bias and thus can be interpreted as true sex differences [65]. The exclusion criteria were neurological disorders, mental retardation, alcohol and substance abuse/ dependence (other than tobacco smoking), major psychiatric disorders and treatment with any psychiatric medication. Fifty-five percent of the participants with tattoo were smokers in contrast to 10% in the non-tattooed women. A semi-structured interview of a 20item measure of tattoo characteristics was administered by a researcher (AK). The control group included 60 women without tattoo, recruited from the same area in a similar age range: 18-35 years old (M=28.5, SD=5.43). Education level in the control group had the following distribution: high school diploma or lower – 25%, first university degree – 28.3%, second university degree – 41.7% and philosophy degree – 5%. All participants completed a screening interview, which covered the following areas: medical history, illicit drug use, family and personal psychiatric history. All of the subjects were free of any psychopharmacologic treatment. Exclusion criteria for the control women without tattoo included any current or past DSM-IV-TR axis I psychiatric disorder. Only 10% of participants from this group smoked regularly.

Narcissistic Personality Inventory (NPI)

NPI is a 40-item measure of Narcissism (M=17.85, SD=7.6, α=.86) [59]. This measure is frequently used in the study of narcissism, particularly in the field of personality psychology, and has been validated using a wide array of criteria for a review, see [53]. NPI is a self-report inventory, based on the DSM-related definition of Narcissism as a continuum, in which extreme manifestations represent pathological narcissism but less extreme forms reflect subclinical narcissistic personality trait [57]. The NPI consists of the following independent but correlated factors: authority (dominance, assertiveness, leadership, selfconfidence), exhibitionism (exhibitionism, sensation-seeking; lack of impulse control), superiority (capacity for status, social presence, selfconfidence), exploitativeness (rebelliousness, nonconformity, hostility, lack of tolerance or consideration of others), vanity (regarding the self, and being judged by others, as physically attractive), self-sufficiency (assertiveness, independence, self-confidence, need-for-achievement), and entitlement (ambitiousness, need-for power, dominance, hostility, lack of selfcontrol and tolerance for others) [59]. The internal reliability of the full scale is .83, with the 7 subscale reliabilities ranging from .50 to .73 [59]. The full scale also has high test-retest reliability after 13 weeks (r = .81); the test-retest reliability on the individual subscales is lower (range: .57 to.80; [66]. A Hebrew version of the questionnaire was developed [67]. Analysis of a normal population showed similar characteristics to those found in studies using this questionnaire in English. Reliability of the Hebrew version was tested using Cronbach’s alpha,which was 0.9 and the validity of the scale was 0.88 [67].

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SAS 9.4 software for Windows. All analyses used two-tailed levels of significance. In the first stage, the parametric t-test was performed to compare groups (tattooed and not-tattooed) differences in demographic variables (age and education) and narcissistic characteristics (authority, exhibitionism, superiority, vanity, exploitative, entitlement and self-sufficiency). In the second stage, the multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to assess the relationship between the presence of tattoo and significant variables identified in the first stage. Multivariate logistic regression models were built using backward stepwise techniques considering variables with a univariate p-value≤0.25 (Hosmer & Lemeshow) as potential independent risk factors. The odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence interval (CI) were assessed for each predictor. A c-index was calculated to evaluate model discrimination, and the HosmerLemeshow test was applied to evaluate model calibration.

Result

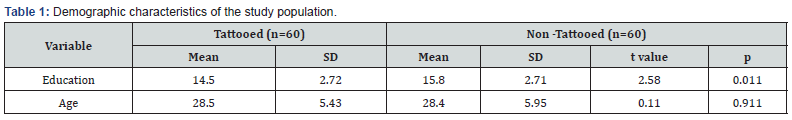

Between-group comparison of the socio-demographic characteristics. There were no statistical differences (on the level p=0.05) in age between the groups (Table 1). Women with tattoos were significantly less educated (t= 2.60, df= 118, p = 0.01) with effect size value of d=0.48, indicating a moderate power. Thus, education was considered as a covariate.

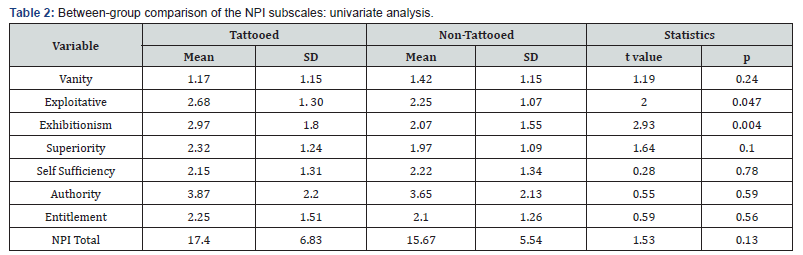

Between-group comparison of the NPI

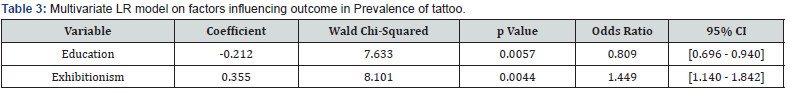

Total NPI scores of both groups were in the normal range. Univariate analysis showed significant differences between women with tattoos and women without tattoos in two NPI subscales: Exploitative (t=2.00, df=118, p=0.0478) and Exhibitionism (t=2.93, df=118, p=0.0041) (Table 2). Cohen’s effect size values for Exploitative (d = 0.36) and for Exhibitionism (d = 0.54) were at the moderate and high ranges, respectively (Table 2). All variables with univariable significance of p<0.25 were included in multivariable analysis. Multivariate backward logistic regression found that education and one narcissistic characteristic - Exhibitionism contributed significantly to a standard logistic regression model aiming to discriminate between participants with and without tattoo (Table 3). Based on the results from the multivariate logistic analysis, an institutional model was developed to predict outcome in tattooed participants. The results showed that the probability (p) of the response fits the equation:

log(9 /1− p) = 2.2492 − 0.2119*Education + 0.3709*Exhibitionism

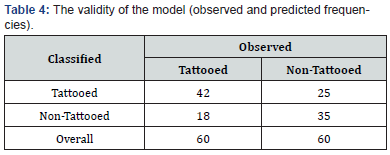

According to the model, education has a negative effect on the presence of tattoo. Participants with a lower education were more likely to have tattoo. The odds ratio of 0.809 shows that increasing education by one-year decreases odds of having tattoo by almost 21%. The Exhibitionism scale has a positive impact on the presence of tattoo, the higher this scale, the more likely that participant would have tattoo. The odds ratio of 1.449 for this scale shows that as this scale increases by one unit the odds of having tattoo, an increase of almost 45%. The resulting model had a c-statistic of 0.713, indicating moderately good discriminative ability. The Hosmer – Lemeshow Goodness of fit test was insignificant (p= 0.979), suggesting that the model fit the data well. The validity of our model with the cut off set 0.5 is presented in Table 4.

Discussion

In contrast to our expectation, total narcissism score on the NPI did not differ between women with and without tattoos. A post hoc analysis (including effect size) detected significant differences between women with and without tattoo only in the Exhibitionism subscale of the NPI. Exhibitionism as a dimension of the NPI includes sensation seeking and attenuation of impulse control [59]. Our observation of an elevated Exhibitionism subscale score in women with tattoo is in accordance with previous studies that demonstrated high scores of “experience seeking” [68] and “sensation seeking” dimensions in tattooed individuals [32,47,69,70]. Our finding is also in line with previous reports that showed that tattooed individuals had significantly lower Conscientiousness [15,52] and Agreeableness [52] on the NEO-PI, and express a significantly higher elevation on the psychopathic deviate scale of the MMPI than individuals without tattoo [71]. . In our previous study we demonstrated that young, tattooed women have difficulty in considering the cost and benefits of their actions [63], which is consistent with the previous observation of high risk-taking behavior in this population. Tate and Shelton [52] found that the “effect sizes of personality differences accounted only for 2% of the variance differences between tattooed and non-tattooed persons”. In the current study, by using the NPI, the effect size values regarding personality differences reached a moderate level. Moreover, only one specific narcissistic trait, namely exhibitionism, discriminated between tattooed and nontattooed young women.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that should be noted. First, we focused on young women (aged 18 to 35 years), thus, our results cannot be applicable to all the tattooed population. Second, we did not assess comorbid personality disorders in our sample, a factor that can affect our findings. Third, most of our young women had a small number of tattoos. It is possible that in women with a large number of tattoos the elevation in NPI scores is larger and not limited to one subscale.

Conclusion

The current study has demonstrated that young women with tattoos have significantly higher levels of exhibitionism and lower level of education than young women without tattoos. The hypothesis that special body ornaments such as tattoos may be a direct expression of exhibitionism warrants further studies including a systematic assessment of the relationship between the number of tattoos, their content and narcissistic personality characteristics.

Competing Interests

SK is an employee of Anima Scan Ltd., however Anima Scan Ltd., did not provide any funding and/or materials for the present study and did not have any role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Financial Disclosure

Neither financial nor material support was received from any external resource for this work. One of the authors of this study, Dr. Kertzman is employed by Anima Scan Ltd but his employment is unrelated to the current study and his salary is in no way compensation for any work done on this study. Additionally, Anima Scan Ltd. did not provide any financial support for this study in any form. Neither did Anima Scan Ltd. play a role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript. Neither financial nor material support was received from any external resource for this work.

Authors’ Contributions

SK-Conceptualization, Methodology, Project Administration, Writing-Original Draft Preparation; AK- Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing-Original Draft Preparation; OH Formal analysis; RL- Conceptualization, Supervision; AWConceptualization, Supervision, Writing-Original Draft Preparation, Writing-Review and Editing.

Acknowledgement

This article is part of Dr. Alex Kagan’s PhD thesis: “Cognitive and Psychological Mechanisms of the Risk Decisions among Women with Tattoos” carried out under the supervision of Prof. Rina Lapidus, and Prof. Abraham Weizmam and with the consultation of Dr. Semion Kertzman conducted in the Program for Hermeneutics and Cultural Studies of the Interdisciplinary Studies Unit at Bar-Ilan University, Ramat Gan, Israel.

References

- DeMello M (2000) Bodies of Inscription: A Cultural History of the Modern Tattoo Community. Durham: Duke University Press, UK.

- Kosut M (2006) Mad Artists and Tattooed Perverts: Deviant Discourse and the Social Construction of Cultural Categories. Deviant Behavior 27(1): 73-95.

- Dann CJ, Callaghan, Fellin L (2016) Tattooed Female Bodies: Considerations from the Literature. Psychology of Women Section Review 18(1): 43-51.

- Madfis E, Arford T (2013) The Dilemmas of Embodied Symbolic Representation: Regret in Contemporary American Tattoo Narratives. The Social Science Journal 50: 547-556.

- Adams J (2009) Marked Difference: Tattooing and its Association with Deviance in the United States. Deviant Behavior 30 (3): 266-292.

- Botz Bornstein T (2013) From the Stigmatized Tattoo to the Graffitied Body: Femininity in the Tattoo Renaissance. Gender, Place & Culture 20(2): 236–252.

- Atkinson M (2004) Tattooing and civilizing processes: Body Modification as Self-control. Canadian Review of Sociology & Anthropology 41: 125-146.

- Lennon SJ, Johnson KK (2019) Tattoos as a Form of Dress: A Review. Fashion, Style & Popular Culture 6(2): 197-224.

- Jagger E (2000) Consumer Bodies. in The Body, Culture and Society: An Introduction, edited by Philip Hancock, Bill Hughes, Elizabeth Jagger, Kevin Paterson, Rachel Russell, Emmanuelle Tulle-Winton, and Melissa Tyler. Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- Koch JR, Roberts AE, Cannon JH, Armstrong ML, Owen DC (2005) College Students, Tattooing, and the Health Belief Model: Extending Social Psychological Perspectives on Youth Culture and Deviance, Social Spectrum. Mid-South Sociological Association 25(1): 79-102.

- Irwin K (2001) Legitimating the First Tattoo: Moral Passage through Informal Interaction. Symbolic Interaction 24(1): 49-73.

- Hennessy D (2011) Ankhs and Anchors: Tattoo as an Expression of Identity-Exploring Motivation and Meaning. Doctor of Philosophy thesis, School of Psychology, University of Wollongong, Australia

- Velliquette AM, Murray JB, Creyer EH (1998) The Tattoo Renaissance: An Ethnographic Account of Symbolic Consumer Behavior. Advances in Consumer Research. Association for Consumer Research 25: 461-467.

- Velliquette AM, Murray JB (2002) Mapping the Social Landscape: Readings in Sociology. Mountain View: Mayfield Publishing Company.

- Swami V (2011) Marked for Life? A Prospective Study of Tattoos on Appearance Anxiety and Dissatisfaction, Perceptions of Uniqueness and Self-Esteem. Body Image 8(3): 237-244.

- Swami V (2012) Written on the Body? Individual Differences between British Adults Who do and do not Obtain a First Tattoo. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 53: 407-412.

- Tiggemann M, Hopkins S (2011) Tattoos and Piercings: Bodily Expressions of Uniqueness? Body Image 8: 245-250.

- Antonellis PJ, Berry G, Silsbee R (2017) Employment Interview Screening: Is The Ink Worth It? Global Journal of Human Resource Management 5(2): 38-53.

- Ellis AD (2015) A Picture is Worth One Thousand Words: Body Art in the Workplace. Employment Responses Rights Journal 27(2): 101-113.

- Burgess M, Clark L (2010) Do the “Savage Origins” of Tattoos Cast a Prejudicial Shadow on Contemporary Tattooed Individuals? Journal of Applied Social Psychology 40(3): 746 -764.

- Dickson L, R Dukes, Smith H, Strapko N (2014) Stigma of Ink: Tattoo Attitudes among College Students. The Social Science Journal 51: 268-276.

- Fisher JA (2002) Tattooing the Body, Making Culture. Body & Society 8(4): 91-107.

- Roberts DJ (2012) Secret Ink: Tattoos Place in Contemporary American Culture. Journal of American Culture 35(2): 153-65.

- Ferguson Rayport SM, Griffith RM, Straus EW (1995) The Psychiatric Significance of Tattoos. Psychiatric Quarterly 29: 112-131.

- Silver E, Van Eseltine M, Silver SJ (2009) Tattoo Acquisition: A Prospective Longitudinal Study of Adolescents. Deviant Behavior 30(6): 511-538.

- Liu CM, Lester D (2012) Body Modification Sites and Abuse History. Journal of Aggression. Maltreatment & Trauma 21(1): 19-30.

- Carroll L, Anderson R (2002) Body Piercing, Tattooing, Self-Esteem, and Body Investment in Adolescent Girls. Adolescence 37(147): 627-637.

- Byard RW, Charlwood C (2014) Commemorative Tattoos as Markers for Anniversary Reactions and Suicide. Journal of Forensic and Legal Medicine 24: 15-7.

- Hicinbothem J, S Gonsalves S, Lester D (2006) Body Modification and Suicidal Behavior. Death Studies 30(4): 351-363.

- Koch JA, Roberts M, Armstrong, D Owen (2010) Body Art, Deviance, and American College Students. The Social Science Journal 47(1): 151-161.

- Dhossche D, Snell KS, Larder S (2000) A Case-Control Study of Tattoos in Young Suicide Victims as a Possible Marker of Risk. Journal of Affective Disorders 59(2): 165-168.

- Drews DC, Allison J (2000) Behavioral and Self-Concept Differences in Tattooed and Non-tattooed College Students. Psychological Reports 86: 475-81.

- Carroll ST, Riffenburgh RH, Roberts TA, Myhre EB (2002) Tattoos and Body Piercings as Indicators of Adolescent Risk-Taking Behaviors. Pediatrics 109: 1021-1027.

- Roberts TA, Ryan SA (2002) Tattooing and High-Risk Behavior in Adolescents. Pediatrics 110: 1058-1063.

- Wohlrab S (2009) Differences in Personality Attributions toward Tattooed and Non-tattooed Virtual Human Characters. Journal of Individual Differences 30: 1-5.

- Houghton SJ, Durkin K, Parry E, Turbett Y, Odgers P (1996) Amateur Tattooing Practices and Beliefs among High School Adolescents. Journal of Adolescent Health 19(6): 420-425.

- Silver E, Silver SR, Siennick S, Farkas G (2011) Bodily Signs of Academic Success: An Empirical Examination of Tattoos and Grooming. Social Problems 58(4): 538-564.

- Forbes GB (2001) College Students with Tattoos and Piercings: Motives, Family Experiences, Personality Factors and Perception by Others. Psychological Reports 89: 774-796.

- Adams J (2009) Marked Difference: Tattooing and its Association with Deviance in the United States. Deviant Behavior 30 (3): 266-292.

- Ross SR, NL Heath (2003) Two Models of Adolescent Self-Mutilation. Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 33(3): 277-287.

- Jennings WG, Fox BH, Farrington DP (2014) Inked into Crime? An Examination of the Causal Relationship between Tattoos and Life-Course Offending among Males from the Cambridge Study in Delinquent Development. Journal of Criminal Justice 42(1): 77-84.

- Stirn A (2007) My Body Belongs To Me"- Cultural History and Psychology of Piercings and Tattoos. Therapeutische Umschau. Revue thérapeutique 64: 115-9.

- Degelman D, Price ND (2002) Tattoos and Ratings of Personal Characteristics. Psychological Reports 90(2): 507-514.

- Favazza AR (1996) Bodies Under Siege: Self-Mutilation and Body Modification in Culture and Psychiatry. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, UK.

- Manuel L, Retzlaff P (2002) Psychopathology and Tattooing among Prisoners. International Journal of Offender Therapy & Comparative Criminology 46(5): 522-531.

- Stephens MB (2003) Behavioral Risks Associated with Tattooing. Family Medicine 35: 52–54.

- Stirn A, Hinz A, Brahler E (2006) Prevalence of Tattooing and Body Piercing in Germany and Perception of Health, Mental Disorders, and Sensation Seeking among Tattooed and Body-Pierced Individuals. Journal of Psychosomatic Research 60: 531-534.

- Grumet GW (1983) Psychodynamic Implications of Tattoos. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry 53: 482-492.

- Blackburn JJ, Cleveland R, Griffin GG, Davis J Lienert, GJ McGwin (2012) Tattoo Frequency and Types among Homicides and Other Deaths, 2007-2008: A Matched Case-Control Study. The American Journal of Forensic Medicine and Pathology 33: 202-205.

- Swami V, Kuhlmann T, Tran US, Voracek M (2016) More Similar than Different: Tattooed Adults are only Slightly More Impulsive and willing to Take Risks than Non-Tattooed Adults. Personality and Individual Differences 88: 40-44.

- Swami V, H Gaughan, Tran US, Kuhlmann T, Stieger S, Voracek M (2015) Are Tattooed Adults Really More Aggressive and Rebellious than Those without Tattoos. Body Image 15: 149-152.

- Tate JC, Shelton BL (2008) Personality Correlates of Tattooing and Body Piercing in a College Sample: The Kids are Alright. Personality and Individual Differences 45: 281-285.

- Morf CC, Rhodewalt F (2001) Unraveling the Paradoxes of Narcissism: A Dynamic Self-Regulatory Processing Model. Psychological Inquiry 12: 177-196.

- Pajor AJ, Broniarczyk Dyła G, Świtalska J (2015) Satisfaction with Life, Self-Esteem and Evaluation of Mental Health in People with Tattoos or Piercings. Psychiatria Polska 49(3): 559-573.

- Kierstein L (2015) Personal Records from my Tattoo Parlour: Deep Emotions Drawn as Life-Long Pictures on the Skin's Canvas. Current Problems in Dermatology 4: 41-48.

- Mifflin M (1997) Bodies of Subversion: A Secret History of Women and Tattoo. New York: Juno.

- Emmons R (1987) Narcissism: Theory and Measurement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52(1): 11-17.

- Emmons RA (1984) Factor Analysis and Construct Validity of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Journal of Personality Assessment 48: 291-300.

- Raskin R, Terry H (1988) A Principal-Components Analysis of the Narcissistic Personality Inventory and Further Evidence of its Construct Validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 54: 890-902.

- Foster JD, Shiverdecker LK, Turner IN (2016) What Does the Narcissistic Personality Inventory Measure across the Total Score Continuum. Current Psychology 35(2): 207-219.

- Raskin RN, Hall CS (1979) A Narcissistic Personality Inventory. Psychological Reports 45(2): 590.

- Raskin RN, Hall CS (1981) The Narcissistic Personality Inventory: Alternative Form Reliability and Further Evidence of Construct Validity. Journal of Personality Assessment 45: 159-162.

- Kertzman S, Kagan A, Hegedish O, Lapidus R, Weizman A (2019) Do Young Women with Tattoos have Lower Self-Esteem and Body Image than their Peers without Tattoos? A Non-verbal Repertory Grid Technique Approach. Plose One 14(1).

- Kertzman S, Kagan A, Vainder M, Lapidus R, Weizman A (2013) Interactions between Risky Decisions, Impulsiveness and Smoking in Young Tattooed Women. BMC Psychiatry 13: 278-286.

- Grijalva E, Newman DA, Tay L, Donnellan MB, Harms PD, Robins RW, Yan T (2015) Gender Differences in Narcissism: A Meta-Analytic Review. Psychological Bulletin 141(2): 261-310.

- Del Rosario PM, White RM (2005) The Narcissistic Personality Inventory: Test–retest Stability and Internal Consistency. Personality and Individual Differences 39: 1075-1081.

- Zamir D (1989) Relationship between Narcissistic and Borderline Personality and Normal Personality Traits. Master's Degree Tel Aviv University, Israel

- Swami V, Pietschnig J, Bert BI, Nader W, Stieger S, Voracek M (2012) Personality Differences between Tattooed and Non-tattooed Individuals. Psychological Reports 111(1): 97-106.

- Roberti JW, Storch EA, Bravata EA (2004) Sensation Seeking, Exposure to Psychological Stressors, and Body Modification in a College Population. Personality and Individual Differences 37: 1167-1177.

- Wohlrab S, Stahl J, Rammsayer T, Kappeler PM (2007) Differences in Personality Characteristics between Body Modified and Nonmodified Individuals and Possible Evolutionary Implications. European Journal of Personality 21: 931-951.

- Kim JJ (1991) A Cultural Psychiatric Study on Tattoos of Young Korean Males. Yonsei Medical Journal 32: 255-262.