Understanding Spiritual Well Being, Forgiveness, Mindfulness and Meaning in Life among Offenders

Deka DB1, Rejani Thudalikunnil Gopalan*2 and Bhave TA3

1 Gujarat Forensic Sciences University, India

2 Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, India.

3Gujarat Forensic Sciences University, India

Submission:October 23, 2019; Published: November 04, 2019

*Corresponding author:Rejani Thudalikunnil Gopalan, Mahatma Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, RIICO Institutional area, Tonk road, Sitapura, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India

How to cite this article:Deka DB, Rejani Thudalikunnil Gopalan, Bhave TA. Understanding Spiritual Well Being, Forgiveness, Mindfulness and Meaning in Life among Offenders. J Forensic Sci & Criminal Inves. 2019; 13(1): 555852. DOI: 10.19080/JFSCI.2019.13.555852.

Abstract

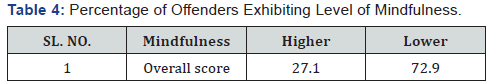

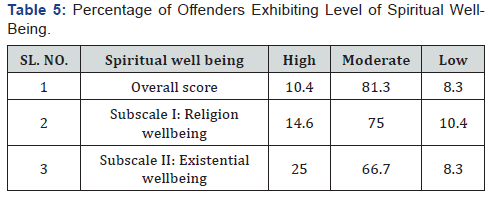

Prisons are society’s correctional institutes. Their existence is to reform the individual from wrongdoing to doing good deeds, from greed to generosity, from being revengeful to being forgiving. Rarely do we associate concepts like spirituality with prisoners. However, it should be noted that the loneliness and suffering in the prison can be a way of awakening deep spirituality as explored in a project “Doing time, doing vipassana” in Delhi’s Tihar Jail Khurana & Dhar [1]. Inmates behind the bars are always seen with a negative connotation, never tried to explore the positive side. Hence the present study aimed to understand the concept of mindfulness, spiritual wellbeing, forgiveness and meaning in life among offenders. The research design used was Cross sectional design. Sample size: Forty-eight adults with illicit background were selected from the prison. Purposive sampling was used for selecting the sample. Assessment tools used includes: The Heartland Forgiveness Scale (HFS), The Toronto Mindfulness Scale (TMS), Spiritual Well Being Scale (SWBS) and Meaning in Life Questionnaire (MLQ). Results identify that 80.1% of the participant shows positive attitude towards meaning in life, 39.6% of the participants shows higher level of forgiveness indicating that one is usually forgiving of oneself, others, and uncontrollable situations. More than quarter of sample (27.1%) reflect higher levels of dispositional mindfulness and 10.4% of the offenders seem to have higher level of spiritual wellbeing.

Keywords: Spiritual wellbeing; Forgiveness; Meaning in life; Mindfulness

Abbreviations: HFS: Heartland Forgiveness Scale; TMS: Toronto Mindfulness Scale; SWBS: Spiritual Well Being Scale; MLQ: Meaning in Life Questionnaire

Introduction and Review

Earlier, Prisons as observed, not only ‘total institutions’ in the sense that they encompass inmates’ lives to an extent qualitatively greater than other social institutions, they are physical places (mostly surrounded by high walls) with a specific history and ethos that are designed to be places of punishment. Prisons bring troubled human beings, often with a long history of violence as victim or offender; Prisons concentrate large numbers of people in crowded conditions with little privacy and few positive social outlets [2] but in 1987 the Supreme Court of the United States ruled that prison inmates retain constitutional rights, including that of religion. This ruling was reinforced in 1993 by the Religious Freedom and Restoration Act Turner [3]. Prisons hold healthy people dealing with issues of loss, fear, shame, guilt and innocence, alongside people with mental illnesses, varying levels of maturity, sociopathic tendencies, and histories of impulsivity and violence. The sense of danger and the generally oppressive nature of prisons make it all the more remarkable that prisons can also be places of reflection, exploration, discovery, change and growth Connor & Duncan [4].

There are many prison stories of conversion leading to successful desistance from crime and a generous life of giving to one’s culture, community, and country. In their article “Why God Is Often Found Behind Bars: Prison Conversions and the Crisis of Self-Narrative” [5], make two important points. Their first point is the lack of social science knowledge about religion and spirituality in this unique context of incarceration. “The jail cell conversion from “sinner” to true believer may be one of the best examples of a “second chance” in modern life, yet the process receives far more attention from the popular media than from social science research.” Their second point is that the discipline of “narrative psychology” can provide explanatory insight into the phenomenon of religious and spiritual conversion in prison. Prisoner conversions, they argue, are a narrative that “creates a new social identity to replace the label of prisoner or criminal, imbues the experience of imprisonment with purpose and meaning, empowers the largely powerless prisoner by Religion, turning him into an agent of God, provides the prisoner with a language and framework for forgiveness, and allows a sense of control over an unknown future.” Maruna [5]. Currently, several general religious/spiritual programs are represented by institutional religions in prisons and a wide variety of specific religious/spiritual programs available at most large prisons. One of the studies indicates a sizeable proportion of inmates are regularly involved in some type of religious/spiritual activity and that these activities are associated with positive social behavior O Connor & Perreyclear [4]. Inmates report a number of reasons for being involved in organized and personal religion/ spirituality as it provides meaning and direction in life. It helps cultivating feelings of faith, hope, and peace through religious/ spiritual experiences like personal meditation and prayer, and also provides opportunities for social support through community worship and interaction Turner [6].

Spirituality, a word used in an abundance of contexts that means different things for different people at different times in different cultures. Although expressed through religions, art, nature and the built environment for centuries, recent expressions of spirituality have become more varied and diffuse Hassed [7]. Spirituality can be defined as one component of wellness, “a continuing search for meaning and purpose in life; an appreciation for the depth of life, the expanse of the universe and natural forces which operate; a personal belief system” Benjamin & Looby [8]. Research has begun to explore how positive emotions, which are typically short-lived, have such powerful effects in people’s lives. broaden-and-build theory emphasizes that positive emotions enable people to thrive because they momentarily broaden their attention and perspective to help them discover and build cognitive, psychological, social, and physical resources. Thus, it seems that positive emotions not only increase satisfaction and well-being in the moment, but also help people build resources that lead to experiencing life as more satisfying and fulfilling in the long term.

Humanistic psychology gives importance to the science of human experience, focusing on the actual lived experience of persons Aanstoos et al, [9]. Spirituality changes over time, in fact, substantial changes can occur during life transitions or in the face of traumatic events Park & Ai [10]. Spirituality includes various themes among them few themes are included in the present study to understand the universal concept of spirituality among the offenders. Spiritual well-being broadly refers to one’s sense of inner peace, connectedness to others, and reverence for life, and encapsulates both religious well-being and existential well-being Mc Clain & Arnold [11,12]. The spirituality issue is very wide, and its measurement is quite complex; the spiritual wellbeing (SWB) is one of its aspects that may be evaluated. SWB is understood as the individual’s subjective perception of well-being in relation to his/her belief. The development of measurement instruments of SWB was based on the concept of spirituality that involves a vertical, religious component (a sense of well-being in relation to God), and a horizontal, existential component (a sense of life purpose and satisfaction); the latter does not imply any reference to a specifically religious content. The spirituality is about issues concerning the meaning of life and the reason for living; it is not limited to some types of beliefs or practices Sousa et al, [13]. Spirituality may or may not entail formal religious practices but relates more generally to people’s propensity to seek meaning in their lives, grow, and transcend beyond the self Mc Clain et al, [11]. Existential well-being refers to a person’s present state of subjective wellbeing across existential domains, such as meaning, purpose, and satisfaction in life, and feelings of comfort regarding death and suffering Cohen et al, [14]. Spiritual well-being is described as a dual status which includes: 1) a vertical dimension referring to well-being in relation to God or a higher power; i.e. referring to the religious element, and 2) a horizontal dimension referring to the purpose and satisfaction from life; i.e. referring to a spiritual or existential component Blount & Ellison [15].

Meaning in life “Ultimately, man should not ask what the meaning of his life is, but rather must recognize that it is he who is asked. In a word, each man is questioned by life; and he can only answer to life by answering for his own life; to life he can only respond by being responsible.” Viktor E. Frankl, Man’s Search for Meaning has conceived of meaning in life as a process of discovery within a world that is intrinsically meaningful. His theory postulates the following: meanings are not invented and can only be found outside the person. The search for a personal idiosyncratic meaning is a primary human motive. Fulfilment of meaning always implies decision-making and this is not understood to result in homeostasis, unlike need satisfaction. According to Frankl, meanings are not arbitrary human creations, but possess an objective reality of their own. There is only one meaning to each situation and this is its true meaning. Individuals are guided by their conscience to intuitively find this true meaning. Frankl’s theory postulates that if individuals do not pursue meaning they may experience an existential vacuum or meaninglessness. Under prolonged conditions the experience of meaninglessness can lead to conditions typified by boredom and apathy. On the contrary, when meaning is pursued individuals experience self-transcendence and profit from its concomitant sense of life satisfaction and fulfilment Wong et al, [16].

Forgiveness considered as one of the pro social behavior that an individual should possess or can acquire with time Snyder & Lopez [17]. Mahatma Gandhi contended that “The weak can never forgive; Forgiveness is an attribute of the strong”. Forgiveness aids psychological healing through positive changes in effect, improves physical and mental health restores a victim’s sense of personal power Exline & Fincham [18,19], In an offender it is considered to be a process (or the result of a process) that involves a change in emotion and attitude. Most scholars view this as an intentional and voluntary process, driven by a deliberate decision to forgive [20,21]. This process results in decreased motivation to retaliate or maintain estrangement from an offender despite their actions and requires letting go of negative emotions toward the offender. Forgiveness helps bring about reconciliation between the offended and offender Hoyt & Paleari [22,23]. It promotes hope for the resolution of real-world intergroup conflict. Theorists differ in the extent to which they believe forgiveness also implies replacing the negative emotions with positive attitudes including compassion and benevolence [24,25] Mindfulness is a time-honored way of improving one’s well-being, happiness and sense of fulfilment.

By moving our life more into the present moment, we relate to the past and the future in a different way and our habitual unhelpful thinking about past and future events drops away, becomes less insistent, and we find right here, right now a more vibrant and alive place to be Thompson [26]. According to Bishop et al, [27] mindfulness is, “A kind of non-elaborative, nonjudgmental, and present-centered awareness in which each thought, feeling, or sensation that arises is acknowledged and accepted as it is.” Mindfulness was developed for much more than dealing with difficult situations in life. It is a whole philosophy of life. Mindfulness means paying attention to the present moment, non-judgmentally and in so doing fully experiencing life. Everyday Mindfulness describes how you can use the ancient techniques of mindfulness in a modern-day context to deal with difficult situations in your life and experience an increased enjoyment and sense of well-being. It may also inspire you to seek further and discover the deeper experiences of mindfulness and meditation in general. Since one of the practices is to scan the whole body for sensations, occasionally people experience their body for the first time, resulting in a richer experience of emotions and life. Thus, in the present study the aim is to explore the level of understanding about spiritual wellbeing, forgiveness, mindfulness and meaning in life among the offenders. Understanding these concepts among the inmates would help develop a positive attitude towards the inmates as well as the professionals can accordingly provide various recreational methods in prison for sound mental health of the prisoners [28-32].

Methodology

Objectives

a) To find out the level of spiritual well-being among offenders.

b) To find out the level of forgiveness among offenders.

c) To find out the level of meaning in life among offenders.

d) To find out the level of mindfulness among offenders.

Research Design

The research design used was cross sectional research design.

Sample size and sampling

Through purposive sampling method, total of 48 inmates were included in this study. This sample consisted of 31 male prisoners and 17 female prisoners. The participants were taken from Sabarmati Central Jail, Ahmadabad.

Inclusion criteria

The offenders who could read and write. The offenders who were within the age range of 20 years to 50 years.

Exclusion criteria

The offenders who could not read and write. The offenders who were not within the age range of 20 years to 50 years.

Tools

To explore the level of mindfulness, spiritual wellbeing, forgiveness and meaning in life of the offenders the following questionnaires were included by the researchers along with a form of socio demographic details:

Socio demographic details: Socio demographic sheet was prepared for gathering the participant’s demographic information and other information related to social and cultural background. It includes questions related to age, sex, years of education, socio economic background, marital status, domicile, type of crime accused of, inquiry into history of substance abuse and years of stay in prison [33,34].

Spiritual well-being scale (SWB): A 20-item measure that assesses perceptions of spiritual quality of life. The measure has two subscales: (1) Religious Well-Being and (2) Existential Well- Being. Responses range from strongly agree to strongly disagree on a 6-point Likert scale. On Reliability tests, the coefficients of 0.93 (SWB), 0.96 (RWB) and 0.86 (EWB). As an index of internal consistency, the alpha coefficients found were 0.89 for the general index, 0.87 for the subscale of RWB and 0.78 for the subscale of EWB.

The meaning in life questionnaire (MLQ): The Meaning in Life Questionnaire assesses two dimensions of meaning in life using 10 items rated on a seven-point scale from “Absolutely True” to “Absolutely Untrue.” The Presence of Meaning subscale measures the how full respondents feel their lives are of meaning. The Search for Meaning subscale measures how engaged and motivated respondents are in efforts to find meaning or deepen. The MLQ has good internal consistency, with coefficient alphas ranging in the low to high .80s for the Presence subscale and mid .80s to low .90s for the Search subscale [35,36].

The heartland forgiveness scale (HFS): is an 18-item, selfreport questionnaire designed to assess a person’s dispositional forgiveness (i.e., one’s general tendency to be forgiving), rather than forgiveness of a particular event or person. The HFS consists of items that reflect a person’s tendency to forgive him or herself, other people, and situations that are beyond anyone’s control (e.g., a natural disaster).

Mindful attention awareness scale (MAAS): The MAAS is a 15-item scale designed to assess a core characteristic of dispositional mindfulness which is a receptive state of mind in which attention, informed by a sensitive awareness of what is occurring in the present, simply observes what is taking place. This is in contrast to the conceptually driven mode of processing, in which events and experiences are filtered through cognitive appraisals, evaluations, memories, beliefs, and other forms of cognitive manipulation. Internal consistency levels (Cronbach’s alphas) generally range from .80 to .90.

Procedure of the study

Initially approval from higher authorities of jail was taken, after that data collection was started. The prisoners were explained about the nature of the study, with their consent, the questionnaires were administered. Any doubts regarding the questionnaires were clarified during the process of administration. After obtaining the required sample, the offenders and the jail authorities were acknowledged for their support and co-operation.

Statistics

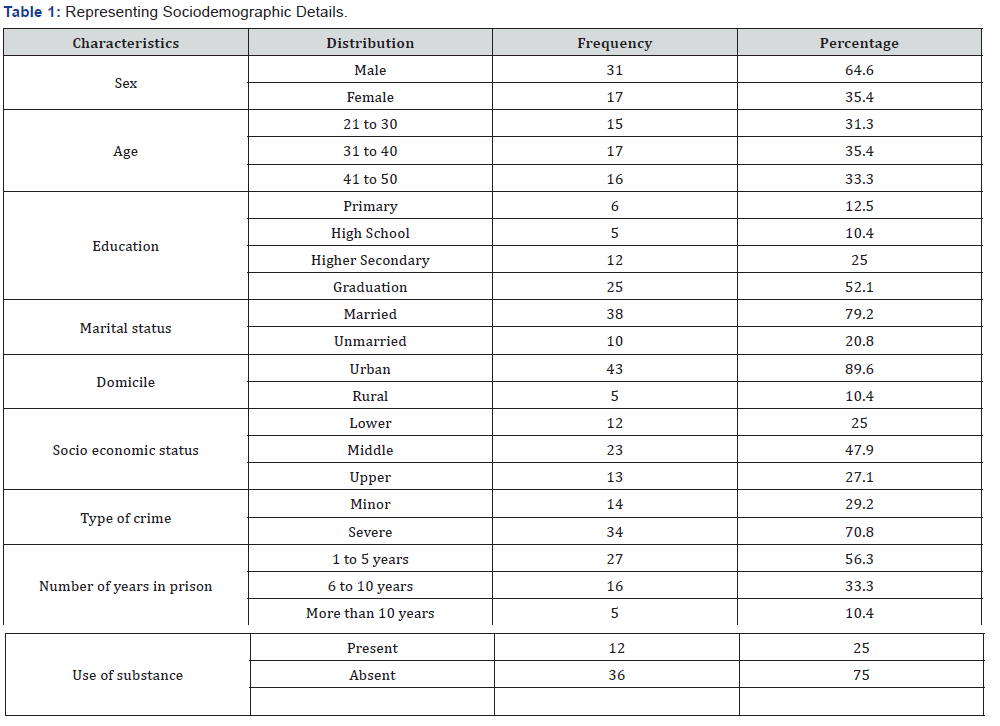

Results were analyzed using descriptive statistics. The table above shows the frequency and percentage of the Sociodemographic details of the offenders. In the table it can be seen that 64.6% of the participants were male and the rest 35.4% were females. Level of education varies from primary to graduation level as few of them were perusing education through distance course in the jail itself. The jail has facilities for educating the prisoners if they wish to continue their education. Among the prisoners 52.1% of them were graduates and 25% of them have completed till higher secondary. Remaining 10.4% and 12.5% have studied till high school and primary level respectively. In the table it can be seen that 79.2% of the prisoners were married. Almost 89.6% of them belong to urban areas and the socio-economic status varies from lower (25.0%), middle (47.9%) and upper (27.1%) class. In the jail 70.8% were there for severe crime such as murder, rape and the rest 29.2% of them were punished for minor crime. Almost 56.2% of them were there in the jail since last 4 to 5 years and 33.3% of them were in the jail since last 6 to10 years and 10.4% of the participants were there for more than 10 years. The above table, the overall scores indicate that 10.4% of the offenders seem to have higher level of spiritual wellbeing and the rest 81.3% and 8.3% of the offenders seem to have moderate and lower level of spiritual wellbeing. On Religion well-being (Sub scale I) 14.6% of the participants were on higher level whereas the remaining 75.0% and 10.4% of the participants were on moderate and lower level of wellbeing respectively. On Existential well-being (Sub scale II) 25.0%, 66.7% and 8.3% of the participants seem to fall on higher, moderate and lower level of well-being [37].

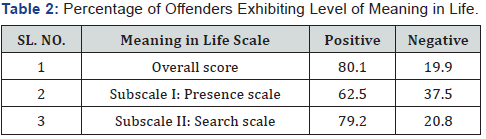

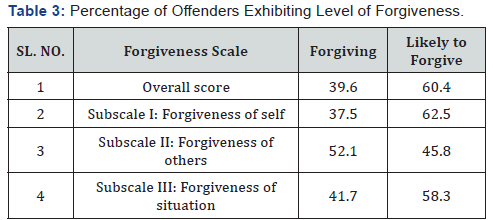

The Table 1 above shows that 39.6% of the participants shows higher level of forgiveness indicating that one is usually forgiving of oneself, others, and uncontrollable situations whereas the rest 60.4% shows moderate level of forgiveness indicating that one is about as likely to forgive, as to not forgive oneself, others, and uncontrollable situations. As per the subscale scores, 37.5% , 52.1% and 41.7% shows higher level of forgiveness indicating that one is usually forgiving of oneself, other people, or uncontrollable situations, respectively whereas 62.5%, 45.8% and 58.3% shows moderate level of forgiveness indicating that one is about as likely to forgive as to not forgive oneself, other people, or uncontrollable situations, respectively. In the above table the overall score shows, 80.1% of the participant shows positive attitude towards meaning in life whereas 19.9% seems to have negative attitude towards meaning in life. As in the Sub scale I, i.e Presence scale 62%.5 and 37.5% of the participants shows positive and negative attitude towards existing meaning in life respectively. As in the Sub scale II, i.e Search scale 62.5% and 37.5% of the participants shows positive and negative attitude towards exploring meaning in life respectively [38]. Unlike the other three scales, scale used for mindfulness (MAAS) do not have any subscales therefore the overall score indicate 27.1% of the participants reflecting higher levels of dispositional mindfulness whereas 72.9% reflecting lower level of dispositional mindfulness.

Discussion

A science of positive subjective experience, positive individual traits and positive institutions promises to improve quality of life and prevent the pathologies [39]. A prison is usually seen with a negative connotation people think that life is barren and meaningless inside the prison. Earlier prisons concentrate large numbers of people in crowded conditions with little privacy and few positive social outlets Homel & Thomson [2]. but with time prison started providing various activities for the inmates, in order to develop pro social behavior, positive thinking and overall personal growth so that they can readjust in the society after they complete the tenure. Life’s meaning is an ever-unfolding and ever-deepening process for an individual. In the present study majority of the participants (80.1%) (Table 2) show positive attitude towards meaning in life. It can be said that participants with positive attitude feel their life has a valued meaning and purpose, and they are still openly exploring that meaning or purpose. 19.9% (Table 2) seems to have negative attitude towards meaning in life [40,41]. Participants with negative attitude probably do not feel their life has a valued meaning and purpose and are not actively exploring that meaning or seeking meaning in their life. As per in the Sub scale I, i.e Presence scale 62%.5 and 37.5% (Table 2) of the participants show positive and negative attitude towards existing meaning in life respectively. Presence of Meaning is positively related to well-being, intrinsic religiosity, extraversion and agreeableness, and negatively related to anxiety and depression. As in the Sub scale II, i.e Search scale 62%.5 and 37.5% (Table 2) of the participants show positive and negative attitude towards exploring meaning in life respectively. Search for Meaning is positively related to religious quest, rumination, past-negative and present-fatalistic time perspectives, negative effect, depression, and neuroticism, and negatively related to future time perspective, close mindedness (dogmatism), and well-being.

Earlier studies have shown that offenders with various types of workshops or training can lead to development of pro social behavior like forgiveness also helps improving interpersonal relationships. Present study show that 39.6% (Table 3) of the participants shows higher level of forgiveness indicating that one is usually forgiving of oneself, others, and uncontrollable situations whereas the rest 60.4% (Table 3) shows moderate level of forgiveness indicating that one is about as likely to forgive, as to not forgive oneself, others, and uncontrollable situations. None of the participant’s overall scores indicate that unforgiving nature of oneself, others, and uncontrollable situations. As per the subscale scores, 37.5%, 52.1% and 41.7% (Table 3) shows higher level of forgiveness indicating that one is usually forgiving of oneself, other people, or uncontrollable situations, respectively whereas 62.5%, 45.8% and 58.3% (Table 3) shows moderate level of forgiveness indicating that one is about as likely to forgive as to not forgive oneself, other people, or uncontrollable situations, respectively.

Only 27.1% (Table 4) of the participants reflect higher levels of dispositional mindfulness in the study and almost 72.9% (Table 4) of the participants reflect lower level of dispositional mindfulness. Previous studies have suggested that mindfulness higher or lower disposition can improve with practice. Mindfulness practice also produces positive effects on psychological well-being. In the present study, the scores indicate that 10.4% (Table 5) of the offenders seem to have higher level of spiritual well-being and the rest 81.3% and 8.3% (Table 5) of the offenders seem to have moderate and lower level of spiritual well-being. On Religion well-being (Sub scale I) 14.6% (Table 5) of the participants were on higher level whereas the remaining 75.0% and 10.4% (Table 2) of the participants were on moderate and lower level of well-being respectively. Similarly, on Existential well-being (Sub scale II) 25.0%, 66.7% and 8.3% (Table 5) of the participants seem to fall on higher, moderate and lower level of wellbeing.

Conclusion

“Positive approach towards the offenders”, few studies in the past have tried to explore the concept of spiritual well-being, forgiveness, meaning in life and mindfulness among the inmates in the jail. Results in the study reflect that almost eighty percent of the prisoners do feel their life has a valued meaning and has a purpose. Most of the participants seem to be positive towards forgiveness indicating that one is usually forgiving of oneself, others, and uncontrollable situations. The results indicate that majority of the offenders show neutral attitude towards spiritual well-being and only few offenders (27%) reflect higher levels of dispositional mindfulness, the rest reflect lower level of mindfulness disposition [42].

Limitations and Future Directions

Future studies in this area can focus on larger sample size and also studies can explore in depth with the various concepts. Study can be more comprehensive if comparative study with other non- offender groups are done.

Implication

Various spiritual and positive factors such as spiritual well-being, forgiveness, meaning in life and mindfulness can lead to positive change in cognition, emotion and behavior. Thus, the findings of this study can help plan intervention and rehabilitation module for the offenders so that with training and knowledge they can be helped to readjust in the society and lead healthy life with positive thoughts and actions.

References

- Homel R, Thomson C (2005) Causes and prevention of violence in prisons. In: Sean O Toole & Simon Eyland (Eds.), Corrections criminology, pp. 101-108.

- Worthington EL (2006) Forgiveness and reconciliation: Theory and practice. Brunner-Routledge, New York, USA.

- O Connor T, Perreyclear M (2002) Prison religion in action and its influence on offender rehabilitation. Religion, the Communiry, and the Rehabilitation of Criminal Offenders 35: 11-33.

- New berry AG, Choi CW, Donovan HS, Schulz RB, Bender C (2013) Exploring spirituality in family caregivers of patients with primary malignant brain tumors across the disease trajectory. Oncol Nurs Forum 40: 119-250.

- Turner RG (2008) Religion in prison: An analysis of the impact of religiousness/ spirituality on behavior, health and well-being among male and female prison inmates in Tennessee. (Doctoral dissertation).

- Hassed CS (2000) Depression: dispirited or spiritually deprived? Med. Jrnl 173(10): 545-547.

- Benjamin P Looby J (1998) Defining the nature of spirituality in the context of Maslow’s and Roger’s theories. Journal of Counselling and Value 42.

- Aanstoos C, Greening T (2000) A History of Division 32 (Humanistic Psychology) of the American Psychological Association. Unification through division: Histories of the divisions of the American Psychological Association. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Park CL, Ai AL (2006) Meaning making and growth: New directions for research on survivors of trauma. Journal of Loss & Trauma 11: 389-407.

- Mc Clain C, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W (2003) Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally ill cancer patients. Lancet 361: 1603.

- Arnold S, Herrick L, Pankratz V, Mueller P (2006) Spiritual well-being, emotional distress, and perception of health after a myocardial infarction. Internet J Adv NursPract 9.

- Sousa PL, Volcan SM, Mari JJ, Horta B (2003) Relação entre bem-estarespiritual e transtornospsiquiátricosmenores: estudo transversal. Rev Saude Publica 37(4): 440-500.

- Cohen R, Mount B, Tomas J, Mount L (1996) Existential wellbeing is an important determinant of quality of life. Cancer 77: 576-586.

- Cooper Effa M, Blount W, Kaslow N, Rothenberg R, Eckman J (2001) Role of Spirituality in Patients with Sickle Cell Disease. Journal of the American Board of Family Practice 14: 116-122.

- Wong E Fry PS (2012) Hand book of Personal Meaning: Theory, Research and Application. (2nd), In: Snyder CR, Lopez SJ (Edt.), (2008) Positive Psychology. The scientific and practical exploration of human strengths. Sage Publications, New Delhi, India.

- Snyder CR, Lopez SJ (2008) Positive Psychology. The scientific and practical exploration of human strengths. Sage Publications, New Delhi, India.

- Exline JJ, Baumeister RF (2000) Expressing forgiveness and repentance: Benefits and barriers. In: ME Mc Cullough, KI Pargament & CE Thoresen (Eds.), Forgiveness: Theory, research and practice.

- Fincham FD, Hall JH, Beach SRH (2005) Til lack of forgiveness doth us part: Forgiveness in marriage.

- Enright RD, Santos, MJ, Al Mabuk R (1989) The adolescent as forgiver. Journal of Adolescence 12(1): 95-110.

- North J (1987) Wrongdoing and forgiveness. Philosophy 62: 336-352.

- Hoyt WT, Fincham F, Mc Cullough ME, Maio G, Davila J (2005) Responses to interpersonal transgressions in families: Forgivingness, forgivability, and relationship-specific effects. J Pers Soc Psychol 89: 375-394.

- Paleari G, Regalia C, Fincham FD (2003) Adolescents willingness to forgive parents: An empirical model. Parenting: Science and Practice 3: 155-174.

- Fincham FD (2000) The kiss of the porcupines: From attributing responsibility to forgiving. Personal Relationships 7: 1-23.

- Kaminer D, Stein DJ, Mbanga I, ZunguDirwayi N (2000) Forgiveness: Toward an integration of theoretical models. Psychiatry 63 (4): 344-357.

- Thompson C (2010) Everyday Mindfulness. A guide to using mindfulness to improve your well-being and reduce stress and anxiety in your life.

- Bishop SR, Mark L, Shapiro S, Carlson L, Anderson LD (2004) Mindfulness: A proposed operational definition. Clinical Psychology: Science & Practice 11(3): 230-241.

- Colman AM (2009) Humanistic psychology: A Dictionary of Psychology. Oxford University Press.

- Colson C (1976) Born Again Chosen Books: Grand Rapids, MI, USA.

- Davis DE, Worthington EL, Hook JN, Van Tongeren DR, Green JD (2009) Relational Spirituality and the Development of the Similarity of the Offender’s Spirituality Scale. Virginia Commonwealth University Psychology of Religion and Spirituality 1(4): 249-262.

- Earle RH, Dillon D, Jecmen D (1998) Systemic approach to the treatment of sex offenders. Sexual Addiction and Compulsivity 5: 49-61.

- Ellerby L, Stonechild J (1998) Blending the traditional with the contemporaryin the treatment of aboriginal sexual offenders: a Canadian experience. In: WL Marshall, YM Fernandez, SM Hudson, Tony Ward (Eds.), Sourcebook of treatment programs for sexual offenders Plenum, New York, USA, pp. 399-415.

- Gandhi M (2000) The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi Veena Kain Publications: New Delhi, India. 51: 1-2.

- GobodaMadikizela P (2002) Remorse, forgiveness and rehumanization: Stories from South Africa. The Journal of Humanistic Psychology 42(1): 7-32

- New berry AG, Choi CW, Donovan HS, Schulz RB, Bender C (2013) Exploring spirituality in family caregivers of patients with primary malignant brain tumors across the disease trajectory. Oncol Nurs Forum 40: 119-250.

- Murphy J, Hampton J (1988) Forgiveness and mercy. Cambridge: University of Cambridge.

- Pelletier G, Verhoef M, Khatri N, Hagen N (2002) Quality of life in brain tumor patients: the relative contributions of depression, fatigue, emotional distress, and existential issues. Jrnl of Neurooncol 57: 41-49.

- Puchalski CS, Shennan S, Mrus JP, Feinberg A, Tsevat J (2006) Spirituality and religion in patients with HIV/AIDS. Journal of General Internal medicine 21: 5-13.

- Steven P, Williams M, Holcomb JE, King W, Buerger ME (2004) Explaining criminal justice. Roxbury Publishing Company, Los Angeles, USA.

- Sardjian A, Nobus D (2003) Cognitive distortions of religious professionals who sexually abuse children. Journal of Interpersonal Violence 18: 905-923.

- Steel P, Ones DS (2002) Personality and happiness: A national-level analysis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83: 767-781.

- Worthington EL (2006) Forgiveness and reconciliation: Theory and practice. Brunner-Routledge, New York, USA.