Unmasking Adherence as a Cause of Unexplained Poor Growth Response in Adolescents Receiving Growth Hormone

Tavia Buysse1, Paul Mandaro1, Carl Thompson2, Richard Noto1*

1Department of Pediatrics, New York Medical College, USA

2Department of Physiology, New York Medical College, USA

Submission: September 18, 2020; Published: November 05, 2020

*Corresponding author:Richard Noto, Diabetes and Endocrine Center for Children and Young Adults 755 North Broadway, Suite 400, Sleepy Hollow, NY 10591, USA

How to cite this article:Tavia Buysse, Paul Mandaro, Carl Thompson, Richard Noto. Unmasking Adherence as a Cause of Unexplained Poor Growth Response in Adolescents Receiving Growth Hormone. J Endocrinol Thyroid Res. 2020; 5(5): 555671. DOI 10.19080/JETR.2020.05.555671

Abstract

Purpose: To evaluate whether a digital record of injections can reveal nonadherence as the cause of unexplained poor growth response in adolescents on growth hormone therapy.

Methods: Twelve adolescent patients receiving growth hormone (GH) treatment who developed unexplained poor growth for six months were identified. Patients were transitioned to a digital record of GH administration (easypod™) from their original method of administration. Growth rates and IGF-I levels prior to and after 3 months of digital monitoring were compared.

Results: Mean age of the 12 participants was 15.6 ±1.9 years and mean duration of GH therapy was 4.5 ±2.7 years. Only one patient acknowledged poor adherence prior to starting easypod, but injection history log showed that five of the patients initially were not adherent with the daily injections. Four of these five patients then became adherent. Mean growth rate of all subjects increased from 2.5 ±2.5cm per year compared to 6.3 ±3.8cm per year after transition to easypod (P<0.01). One patient remained poorly adherent for the duration of the study and two of the twelve patients remained poorly growing even though proven to be adherent to GH therapy by the digital injection record. These 3 patients discontinued GH therapy. There was no significant change in serum IGF-I levels before and after easypod use (P=0.25).

Conclusion: A digital record of injections is useful in revealing nonadherence as the cause of unexplained poor growth response in adolescent

Keywords: Growth hormone;Poor growth response;Growth hormone adherence; Adolescents; Easypod

Abbreviations: GH: Growth Hormone;GR: Growth Rate;IGF-I: Insulin-Like Growth Factor I;HSDS: Height Standard Deviation Score

GH: Growth Hormone;GR: Growth Rate;IGF-I: Insulin-Like Growth Factor I;HSDS: Height Standard Deviation Score

Introduction

Treatment adherence in patients affected by chronic health conditions is a well-known issue, particularly in the adolescent population [1-4]. Low adherence to growth hormone (GH) therapy is a major cause of treatment failure, with nonadherence rates estimated to be as high as 82% [5-10]. Poor adherence to GH treatment correlates with lower growth rates and may prevent patients from reaching their full adult height potential [9-14]. Patient questioning and other methods of estimating GH adherence, such as prescription renewal rates, are not reliable ways of measuring medication adherence [1,4,5,9]. Patients are subject to recall bias and prescription records cannot demonstrate that the GH was taken according to the prescribed regimen [1,5,9]. Furthermore, when questioned about adherence to GH therapy, many patients admit to ‘white coat adherence,’ in which patients follow their prescribed medication regimen only for a few days leading up to their next appointment [1]. Adherence declines with duration of therapy, and adolescents have the lowest rates of GH adherence [1,8,9,15-17].

The easypod™ (Merck Serono International SA, Geneva, Switzerland) electronic auto-injector is a delivery device intended to simplify growth hormone administration, but also allows for accurate monitoring of treatment adherence by keeping an electronic log of the patient’s injection history [18-20]. Many previous studies have shown that patients using easypod have good adherence rates that correspond to optimal growth rates [15,21-23]. However, these reports focus on children and young adults who have been treated with GH for a relatively short amount of time, generally 1 year or less. In this study, we retrospectively evaluated adolescents with unexplained poor growth response to GH therapy who were transitioned to a digital record of growth hormone administration to determine if their poor growth response could be attributed to nonadherence.

Methods

A retrospective, observational monocentric study was performed at the Pediatric Endocrinology Clinic of Boston Children’s Health Physicians, Sleepy Hollow, New York. Twelve adolescent patients with previously optimal growth response to GH treatment who later developed poor growth response for a period of at least six months were identified. Patients were excluded for identified alternative reasons for poor growth, such as low insulin-like growth factor I (IGF-I), hypothyroidism, poor weight gain/loss, or onset of a chronic illness such as celiac disease. Poor growth response was defined as preadolescent or adolescent growth rate less than 5cm or 7cm per year, respectively. Patients were then transitioned to a digital record of GH administration from their original administration method and followed for response to treatment.

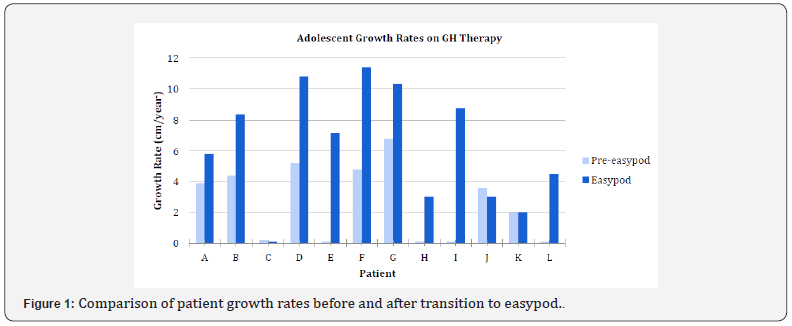

The digital recording system used in this study was the easypod™ device. Easypod documents the dose, date, and time of each injection it delivers, as well as the injection history and number of remaining doses in the cartridge [18-20]. Growth rate (GR) during the easypod period was measured and compared to growth rate of patients prior to the transition. Adherence to GH treatment was defined as missing fewer than 4 injections per month. If patients were found to be poorly adherent based on the injection history data, GR was measured for an additional three-month period to further determine if adherence with the treatment regimen was achieved. Serum IGF-I concentrations were measured by various commercial laboratories using standard assays. A GH peak of less than or equal to 10 ng/mL on stimulation was defined as GHD. Those with levels greater than 10 ng/mL were classified as ISS. GH levels were measured at our in-house endocrine laboratory via the chemiluminescent assay technique [24] (Figure 1).

Statistics: Paired t-tests were used to determine if there was a statistically significant difference in growth rate or IGF-I before and after using easypod. Analysis was performed in NCSS version 12 (NCSS Statistical Software, Kaysville, Utah).

Ethics: Ethical approval by an IRB for the analysis in this paper was not required as this study used secondary pre-existing data from de-identified subjects.

Results

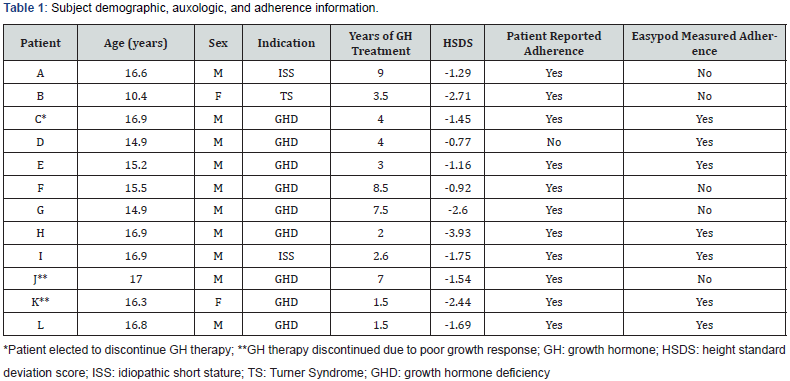

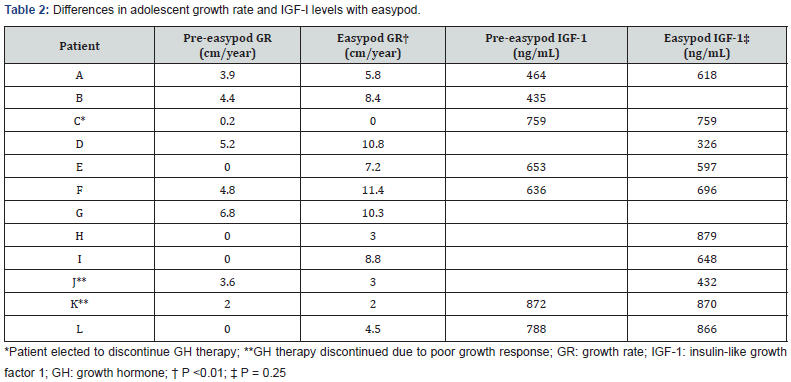

Table 1 depicts subject demographic, auxologic, and adherence data. Twelve patients, 10 male and 2 females, were included in this study. Mean age of study participants was 15.6 ±1.9 years. Patients had been on GH therapy for a mean of 4.5 ±2.7 years and a minimum of 1.5 years. Baseline height standard deviation scores (HSDS ranged from -0.77 to -3.93 with a mean of -1.85 ±0.91. Mean growth rate of patients receiving GH prior to initiating easypod was 2.5 ±2.5cm per year. Mean growth rate of all patients using easypod for 3 months was 6.3 ±3.8cm per year. The difference in growth rates was found to be significant (P<0.01). All but one of the twelve patients prior to easypod transition reported good adherence to GH therapy. Easypod data showed that five of the twelve patients initially were not adherent with the daily injections, and four of these five became adherent by the end of the study. One patient remained poorly adherent and elected to discontinue GH therapy (subject C).

Two of the twelve patients (subjects J, K) remained poorly growing even though proven to be adherent to GH therapy by easypod, and GH therapy was discontinued. When directly questioned about adherence to GH therapy, several patients admitted to taking GH injections only in the days leading up to appointments. When asked about adherence, the mother of one patient stated she was giving all GH injections and no doses were missed. However, easypod data determined that no injections were administered over 3 months of prescribed easypod therapy. When queried about this discrepancy, the mother turned to the child and said, “You told me you were giving all the injections.” Of the patients with paired pre- and post-intervention IGF-I data, there was no significant difference in serum IGF-I with use of easypod (P=0.25), and IGF-I levels were within normal range (Table 2).

Discussion

Successful growth hormone treatment relies on long term and sustained adherence to a daily dosing regimen [5,8,25]. Early detection of nonadherence to GH therapy is important for patients to fully attain their predicted adult height potential [13]. Due to a myriad of reasons, adolescents are known to have lower adherence rates than children of other ages [2,8,16,26-28]. Common factors contributing to nonadherence include chronicity of treatment, misperceptions of consequences of missed doses, pain, and complexity of treatment regimen [2,5,8,9,17]. Electronic records of growth hormone administration offer the opportunity for objective measures of adherence, which can improve treatment outcomes. This observational study focused on a population particularly at risk for nonadherence, given the mean subject age of 15.6 years and mean duration of GH therapy of 4.5 years. Of the twelve subjects studied, one subject was persistently nonadherent and GH therapy was discontinued.

Two subjects were shown to be adherent but poorly responsive to GH therapy while using easypod, and GH therapy was also discontinued. In these two patients, easypod allowed us to determine that they had little potential for growth and would no longer benefit from GH therapy. All the remaining 9 patients showed significantly increased growth rates on easypod therapy. Five were clearly shown to be nonadherent, and one can assume the remaining four were nonadherent since they demonstrated improved growth once starting easypod therapy. The results of this study are not directly comparable to other studies on GH adherence, as the patient population studied here differs considerably from the existing literature. Current publications on efficacy and adherence to GH focus on younger age groups with adequate growth response, often naive to GH therapy [11,15,16,23,29,30].

To our knowledge, this is the first study of its kind to evaluate the effect of easypod on growth rates in adolescent patients who developed unexplained secondary growth failure. Serum IGF-I levels are regularly monitored by physicians to adjust GH dosing, but IGF-I levels are influenced by many factors and a strong correlation between IGF-I and adherence has not been validated [5,11,21-23,31]. Recent studies have reported conflicting evidence for an association between serum IGF-I and adherence to GH treatment [11,21-23]. In our study, IGF-I levels before and after easypod use were not shown to be significantly different (P=0.25). The reason for this lack of consensus may lie in short term adherence occurring prior to office visits and blood testing, as was reported by patients in our study. Thus, further research is needed to elucidate the relationship between GH adherence and IGF-I.

The present study is limited by several factors. Our small subject population and retrospective analysis of data prevented us from establishing equivalent numbers of males and females and evaluating changes in height SDS during sustained easypod use. Despite our small number of patients, we were able to demonstrate a significant increase in growth rate (P<0.01). Furthermore, the observational nature of the study makes it more likely to reflect actual clinical practice. Based on this, larger studies may be able to show even stronger, more generalizable results.

Adherence was treated as a categorical variable in our study, and the exact percentage of GH doses received was not quantified. If adherence had been quantified prior to transition to easypod, a direct correlation between adherence and growth rates would be established. Future research on this population should evaluate the amount of potential height loss with different levels of nonadherence. The duration of adherence follow-up in our study was limited to 3 months. Determination of persistent adherence in this population requires further study. The results of our study strongly indicate, nevertheless, that a digital record of injections can unmask poor adherence as the underlying cause of unexplained poor growth response in adolescents.

Conclusion

Nonadherence to growth hormone treatment is an important cause of treatment failure in adolescents. Objective measures of adherence are necessary for optimal response to growth hormone therapy. The present study demonstrates a digital record of injections can reveal nonadherence as the cause of unexplained poor growth response in adolescents.

References

- Arrabal VelaM A, García Gijón C P, Pascual Martin M, Benet Giménez I, Áreas del Águila V, et al. (2018) Adherence to somatotropin treatment administered with an electronic device. Endocrinologia, Diabetes y Nutricion, 65(6): 314-318.

- Aydin B K, Aycan Z, Şiklar Z, Berberoǧlu M, Öcal G, et al. (2014) Adherence to growth hormone therapy: Results of a multicenter study. Endocrine Practice 20(1): 46-51.

- Bozzola M, Pagani S, Iughetti L, Maffeis C, Bozzola E, et al. (2014) Adherence to growth hormone therapy: A practical approach. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 81(5): 331-335.

- Cassorla F, CianfaraniS, HaverkampF, Labarta J, Loche S, et al. (2011) Growth Hormone and Treatment Outcomes: Expert Review of Current Clinical Practice. Pediatr EndocrinolRev (PER) 9(2): 554-565.

- Centonze C, Guzzetti C, Orlando G, Loche S, Angeletti C, et al. (2019) Adherence to growth hormone (GH) therapy in naïve to treatment GH-deficient children: data of the Italian Cohort from the Easypod Connect Observational Study (ECOS). EndocrinolInvest 42(10): 1241-1244.

- Cutfield W S, Derraik J G B, Gunn A J, Reid K, Delany T, et al. (2011)Non-compliance with growth hormone treatment in children is common and impairs linear growth. PLoS ONE6(1): e16223.

- Dahlgren J (2008)Easypod: A new electronic injection device for growth hormone. Expert Rev Med Devices 5(3): 297-304.

- Desrosiers P M, OBrien F, Blethen S (2005) Patient outcomes in the GHMonitor: The effect of delivery device on compliance and growth. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev, 2(Supp 3): 327-331.

- Drake W M, Howell S J, Monson J P, Shalet S M (2001) Optimizing GH therapy in adults and children. Endocr Rev, 22(4): 425-450.

- Fisher B G, Acerini C L (2013) Understanding the growth hormone therapy adherence paradigm: A systematic review. Hormone Research in Paediatrics 79(4): 189-196.

- Harris M, Hofman P L, Cutfield W S (2004) Growth Hormone Treatment in Children: Review of Safety and Efficacy. Pediatr Drugs 6(2): 93-106.

- Hartmann K, Ittner J, Müller-Rossberg E, Schönau E, Stephan R, et al. (2013) Growth Hormone Treatment Adherence in Prepubertal and Pubertal Children with Different Growth Disorders. Hormone Research in Pediatrics 80(1): 1-5.

- Haverkamp F,Gasteyger C (2011) A review of biopsychosocial strategies to prevent and overcome early recognized poor adherence in growth hormone therapy of children. J Med Econ14(4): 448-457.

- Haynes R B, McDonald H P, Garg A X (2002) Helping patients follow prescribed treatment: Clinical applications. JAMA 288(22): 2880-2883.

- Immulite Siemens (2002) Siemens immulite. Los Angeles, CA, USA.

- Kapoor R R, Burke S A, Sparrow S E, Hughes I A, Dunger D B, et al. (2008) Monitoring of concordance in growth hormone therapy. Arch Dis Child 93(2): 147-148.

- Kirk J (2009) Improving adherence to GH therapy with an electronic device: First experience with easypod. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 6(Supp 4): 549-552.

- Koledova E, Stoyanov G, OvbudeL, Davies P S W (2018) Adherence and long-term growth outcomes: Results from the easypodTM connect observational study (ECOS) in pediatric patients with growth disorders. EndocrConnect 7(8): 914-923.

- Lion FX (2010) Electronic Recording of Growth Hormone Dosing History: The Easypod(TM) Auto-Injector. Current Drug Therapy 5(4): 271-276.

- Loche S, Salerno M, Garofalo P, Cardinale G M, Licenziati M, et al. (2016) Adherence in children with growth hormone deficiency treated with r-hGH and the easypodTM device. Journal of Endocrinological Investigation 39(12): 1419-1424.

- Maggio M C, Vergara B, PorcelliP, Corsello G (2018) Improvement of treatment adherence with growth hormone by easypodTM device: Experience of an Italian centre. Ital J Pediatr 44(1): 113.

- Osterberg L, Blaschke T (2005) Adherence to medication. New England Journal of Medicine 353(5): 487-497.

- Oyarzabal M, Aliaga M, Chueca M, Echarte G, UliedA (1998) Multicentre survey on compliance with growth hormone therapy: What can be improved? Acta Paediat 87(4): 387-391.

- Postlethwaite R J, Eminson D M, Reynolds J M, Wood A J, Hollis S (1998) Growth in renal failure: A longitudinal study of emotional and behavioural changes during trials of growth hormone treatment. Arch Dis Child 78(3): 222-229.

- Rapoff M A (1999) Adherence to Pediatric Medical Regimens. In: M C Roberts, A M La Greca(eds.) Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, New York, USA

- Rees L (1997) Compliance with growth hormone therapy in chronic renal failure and post-transplant. Pediatric Nephrology, 11(6): 752-754.

- Rodríguez Arnao, Rodríguez Sánchez A, Díez López I, Ramírez Fernández J, Bermúdez de la Vega J A, et al. (2019) Adherence and long-term outcomes of growth hormone therapy with easypodTM in pediatric subjects: Spanish ECOS study. Endocr Connect8(9) 1240-1249.

- Rosenfeld R, Bakker B(2008) Compliance and persistence in pediatric and adult patients receiving growth hormone therap. Endocr Pract 14: 143-154.

- Saz-Parkinson Z, Granados M del S, Amate Blanco J M (2013) Study of Adherence to Recombinant Growth Hormone Treatment of Children with a Gh Deficiency: Contributions to Treatment Control and Economic Impact. Agencia de Evaluacion de TecnologiasSanitarias (AETS)70.

- Tauber M, Payen C, Cartault A, Jouret, B, Edouard T, et al. (2008) User trial of EasypodTM, an electronic autoinjector for growth hormone. AnnEndocrinol 69(6): 511-516.

- Yang C, HaoZ, Yu D, Xu Q, Zhang L (2018) The prevalence rates of medication adherence and factors influencing adherence to antiepileptic drugs in children with epilepsy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Epilepsy Res 142: 88-99.