Management in A Patient with Cardiomyopathy and Thyrotoxicosis: A Challenging Decision

Timothy K Eng*, Parag Mehta, Judith Giunta and Brian Wong

Department of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital, USA

Submission: September 10, 2020; Published: October 08, 2020

*Corresponding author:Timothy K Eng, Department of Medicine, New York Presbyterian Brooklyn Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn NY, 11215, USA

How to cite this article:Timothy K E, Parag M, Judith G, Brian W. Management in A Patient with Cardiomyopathy and Thyrotoxicosis: A Challenging Decision. J Endocrinol Thyroid Res. 2020; 5(4): 555670. DOI: 10.19080/JETR.2020.05.555670

Abstract

Background: It is not uncommon to encounter a patient with cardiomyopathy and a concomitant thyroid disorder. However, management becomes complex and potentially life-threatening if the patient has an arrhythmia with hypotension.

Case: 55-year-old male with a history of nonischemic cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation and cocaine use presented with recurrent implanted cardiac defibrillator shocks. On presentation, he was hypotensive with a blood pressure of 88/62. Electrocardiogram showed Atrial Fibrillation with rapid ventricular response with a rate of 144 beats per minute. He was started on amiodarone bolus and transitioned to a drip. He was subsequently found to have thyroxine levels four times the upper limit of normal. His amiodarone was discontinued, and he was started on dofetilide, methimazole, and oral prednisone. After 3 days of treatment, his heart rate remained elevated and borderline hypotensive. He was then started Propranolol with stabilization of his vital signs and discharged home in two days.

Conclusion: Initiation of propranolol should be carefully considered in patients with known cardiomyopathy and concurrent thyrotoxicosis. There is high risk of developing cardiogenic shock and potentially even death.

Keywords: Heart Failure Reduced Ejection Fraction; Cardiomyopathy; Thyrotoxicosis; Propranolol

Abbreviations: NYHA: New York Heart Association; T4: Thyroxine; T3: Triiodothyronine; HR: Heart Rate; ICD: Implanted Cardiac Defibrillator; EKG: Electrocardiogram; BPM: Beats Per Minute; JVD: Jugular Venous Distension; TSH: Thyroid Stimulating Hormone; AIT: Amiodarone Induced Thyrotoxicosis

Introduction

Severe thyrotoxicosis can result in cardiomyopathy if left untreated due to decreased systemic vascular resistance and uncontrolled tachycardia. However, it is uncommon to see patients with known cardiomyopathy develop severe thyrotoxicosis [1-4]. There is increased mortality in hyperthyroid patients with NYHA Class II and III Heart Failure [5,6]. Tachycardia in patients with cardiomyopathy is attributed to compensation to maintain adequate cardiac output. Beta blockers are generally avoided in the setting of hypotension due to the negative ionotropic properties and concern for cardiogenic shock [7]. As per the European Society of Cardiology guidelines, amiodarone is frequently used instead for rate control but both amiodarone and dofetilide are used as medical therapy for rhythm control.

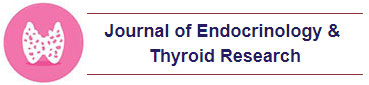

Elevated thyroid hormone levels result in the upregulation of cardiac beta receptors and enhances myocardial sensitivity to sympathetic innervation [8]. It can also cause peripheral vasodilation, resulting in increased cardiac output [1]. The increased metabolic rate have significant implications in a patient with cardiomyopathy. Propranolol is a vital component in the treatment of severe thyrotoxicosis. Propranolol is a nonselective beta blocker usually used in multiple cardiac and psychiatric conditions. Propranolol use inhibits deiodinase which is an enzyme that activates peripheral conversion of the less active thyroid hormone T4 to the more biologically active form T3 (Figure 1).

Propranolol can also provide symptomatic relief by decreasing beta-adrenergic tone which results in decreased heart rate and tremors, which is commonly seen in thyrotoxicosis. In this case, the patient presented with arrhythmia and was hypotensive. Despite use of Class III antiarrhythmic, his HR remained uncontrolled. A difficult decision was made to use propranolol for treatment despite risk of developing cardiogenic shock as patient was borderline hypotensive.

Case Report

A 55-year-old male with a history of nonischemic cardiomyopathy, atrial fibrillation and recent cocaine use presented with acute onset of recurrent ICD shocks. Subjectively he reported intermittent chest pain associated with his ICD firing but without any shortness of breath. On presentation, he was hypotensive w a BP of 88/62 and tachycardic with an EKG showing Atrial Fibrillation and HR 144 BPM. On exam, he was euvolemic without JVD or lung crackles. ICD interrogation revealed atrial fibrillation with ventricular rates up to 200 BPM. He was loaded with Amiodarone on admission.

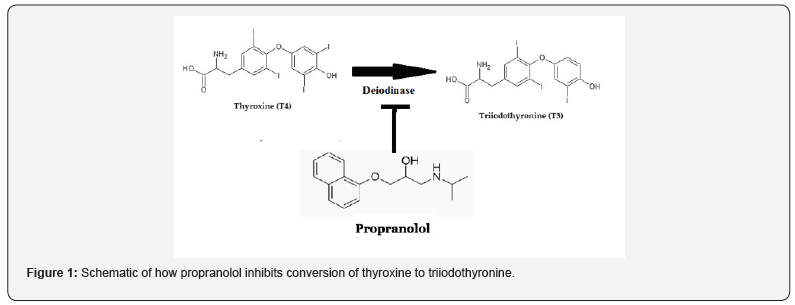

The next day, he was found to have severe thyrotoxicosis with FT4 level of 4.48 and FT3 of 13.48. His total T4 was 22 and TSH was undetectable. Amiodarone was discontinued and the patient was started on dofetilide. Endocrinology was consulted and he was subsequently started on methimazole and prednisone for severe thyrotoxicosis. His Burch-Wartofsky-Score was 45 for cardiac arrhythmia and HR >140 (Figure 2). Laboratory workup revealed negative thyroglobulin antibody, thyroid peroxidase antibody and thyroid stimulating immunoglobulin.

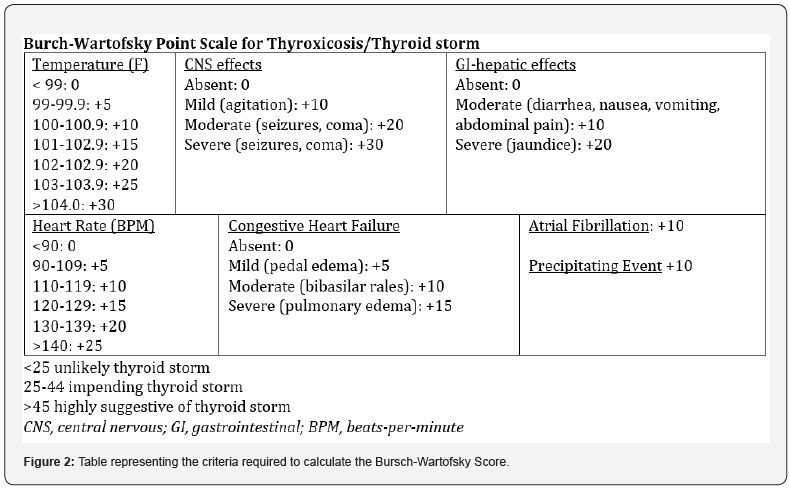

On day 3 of treatment, the patient remained in the telemetry unit as his heart rate raced up to 200 (Figure 3). His blood pressure was also fluctuating around the 90s systolic. He remained euvolemic and was only symptomatic with palpitations. After a multidisciplinary discussion, the patient was started on propranolol as an attempt to control the heart rate despite the risk of decreasing cardiac output. His heart rate and blood pressure stabilized, and he was discharged home in two days.

The Patient followed up with outpatient endocrinology via telemedicine after 2 weeks with labs which showed downtrending of FT4 levels. He remained asymptomatic at that time. Patient was readmitted 1 month after discharge with recurrent ICD shocks. It was revealed that he consumed cocaine and was noncompliant with his propranolol therapy. Medications were restarted and he was counseled on cocaine use cessation. Since then, patient remains compliant with medications and is asymptomatic. Currently, he is pending outpatient workup for his thyrotoxicosis.

Discussion

There are case reports where the use of propranolol resulted in cardiogenic shock in patient with cardiomyopathy and thyroid storm [2]. On the contrary, there are also case studies that showed patients can be successfully treated with propranolol [1]. Currently, there are no official guidelines about the use of propranolol in setting of cardiomyopathy and thyrotoxicosis. There has been suggestion to use esmolol due to its titratable dosing as an attempt to control the arrhythmia [2]. However, propranolol was used due to its effect to prevent conversion from T4 to T3. This patient has good functional status, and he was categorized as NYHA Class 1. This may have attributed to his positive outcome as poor outcomes are known to be associated with NYHA Class II & III.

This patient has a history of nonischemic cardiomyopathy, but the etiology of his cardiomyopathy is unclear. It is possible that he had underlying thyroid dysfunction that led to his heart failure, but he has never had TSH checked in the past. It is also possible that years of cocaine abuse contributed to his cardiomyopathy. In order to differentiate, may consider cardiac catheterization to determine if cardiac output is elevated or low [4]. This can be considered if patient is acutely ill. Literature suggests that treatment of the underlying thyroid dysfunction with beta blockade can help improve cardiac function in thyroid induced cardiomyopathy.

To date, no further workup was available to determine the cause of his thyrotoxicosis. Workup included negative thyroid stimulating immunoglobulins, thyroid peroxidase, thyroglobulin antibodies Further workup would include a thyroid ultrasound or thyroid scan. Differentials include Graves’ disease, toxic multinodular goiter and/or amiodarone induced thyrotoxicosis (AIT). AIT is known to present after weeks to months of amiodarone consumption [3]. This patient was known to be on amiodarone as an outpatient but remains unclear if he was compliant. Amiodarone in general can be continued in the setting of AIT if the patient was being treated with antithyroid medications. However, clinical judgement was used to switch to dofetilide, which is the only other Class III antiarrythmic indicated for rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation with cardiomyopathy [9].

Conclusion

Initiation of propranolol should be carefully considered on a case to case basis. This case highlights the dilemma of managing both heart failure and thyrotoxicosis with unstable vital signs. Ultimately, judicious, and careful use of propranolol should be carefully titrated in a monitored setting. Use of this medication can be lifesaving and improve outcomes but it can also cause clinical deterioration. It should be considered when other treatment modalities has failed.

References

- Sourial K, Borgan SM, Mosquera JE, Abdelghani L, Javaid A (2019) Thyroid Storm-induced Severe Dilated Cardiomyopathy and Ventricular Tachycardia. Cureus 11(7): e5079.

- Abubakar H, Singh V, Arora A, Alsunaid S (2017) Propranolol-Induced Circulatory Collapse in a Patient with Thyroid Crisis and Underlying Thyrocardiac Disease: A Word of Caution. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 5(4): 2324709617747903.

- Yamamoto JM, Katz PM, Bras JAF, Leigh Anne Shafer, Alexander A Leung, et al. (2018) Amiodarone‐induced thyrotoxicosis in heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction: A retrospective cohort study. Health Sci Rep 1(5):e36.

- Eliades M, El-Maouche D, Choudhary C, Zinsmeister B, Burman KD (2014) Takotsubo cardiomyopathy associated with thyrotoxicosis: a case report and review of the literature. Thyroid24(2):383-389.

- Mitchell JE, Hellkamp AS, Mark DB, Jill Anderson, George W Johnson, et al. (2013) Thyroid function in heart failure and impact on mortality. JACC Heart Fail1(1):48-55.

- Kannan L, Shaw PA, Morley MP, Jeffrey Brandimarto, James C Fang, et al. (2018) Thyroid Dysfunction in Heart Failure and Cardiovascular Outcomes. Circ Heart Fail11(12):e005266.

- Teerlink JR, Alburikan K, Metra M, Rodgers JE (2015) Acute decompensated heart failure update. CurrCardiol Rev 11(1): 53-62.

- Osuna PM, Udovcic M, Sharma MD (2017) Hyperthyroidism and the Heart. Methodist Debakey Cardiovasc J13(2):60-63.

- Piotr Ponikowski, Adriaan A Voors, Stefan D Anker, Héctor Bueno, John G F Cleland, et al.(2016) 2016 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure: The Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC)Developed with the special contribution of the Heart Failure Association (HFA) of the ESC. Eur Heart J 37(27):2129-2200.