Ovarian Morphology by Ultrasound Imaging in Adolescents with PCOS and Age-Matched Controls

Asanidze Elene* and Khristesashvili Jenaro

Faculty of Medicine, Tbilisi State University, Georgia

Submission: August 21, 2019; Published: September 30, 2019

*Corresponding author:Asanidze Elene, Faculty of Medicine, Center for Reproductive Medicine Universe, Tbilisi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia

How to cite this article:Asanidze Elene, Khristesashvili Jenaro. Ovarian Morphology by Ultrasound Imaging in Adolescents with PCOS and Age-Matched Controls. J Endocrinol Thyroid Res. 2019; 5(1): 555653.DOI: 10.19080/JETR.2019.05.555653

Abstract

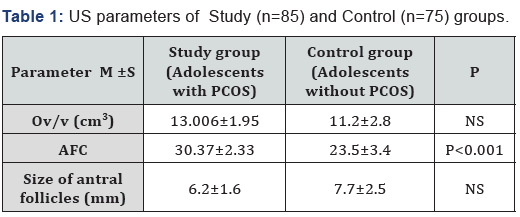

We determined the efficiency of ultrasound imaging (US) usage in adolescents for the diagnosis of PCOS, by comparing ovarian morphology in adolescent girls with and without polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) using a US study that involved 160 adolescents (13 -19 years): 85 with PCOS (study group) and 75 healthy adolescents (control group). Results indicate that ovary volume and mean follicle size in PCOS adolescents and controls did not differ significantly, but AFC in PCOS patients were significantly higher than in controls p<0.001.

Keywords:Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS); Adolescent̕s health; Adolescent ovarian size; Ovarian morphology

Introduction

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) has a leading place in women’s infertility and is a main cause of menstrual dysfunction and hyperandrogenism in adolescents, with potentially significant lifelong consequences [1]. PCOS is a lifelong disease, its manifestation starts during puberty, often at menarche, and continues to the postmenopausal period [2]. The difficulty of diagnosing PCOS in the adolescent is tied in with the challenge in differentiation between PCOS manifestations with physiologic puberty. Menstrual cycle disorders, clinical manifestations of hyperandrogenism such as acne and insulin resistance (developed secondary to increase of Growth hormone) are physiologically characteristic for this age group. Currently, for diagnosis of PCOS, the criteria adopted by Rotterdam Consensus in 2003 [3] is also used in adolescents. Ovarian morphology was introduced as one of the Rotterdam diagnostic criteria for PCOS. Different parameters to study ovarian morphology using ultrasonography have been proposed, but there is still no consensus about their diagnostic value in adolescents [4,5]. Despite the importance of a diagnosis of PCOS at adolescence, available data is still limited, and the results have been much different. Thus, further investigations and data collection in this direction should be considered reasonable and highly important.

Objective

To compare ovarian morphology in adolescent girls with and without polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) using US imaging.

Materials and Methods

160 adolescents (14 -19 years, more than 2 years post menarche; mean age 17±2.3) were involved in a prospective, open-label study. Adolescents were divided into two groups: Study group -85 adolescents with PCOS and Control group - 75- age matched healthy adolescents. PCOS patients met all 3 diagnostic criteria of the Rotterdam consensus (2003), including the exclusion of other related diseases [3]. Study was conducted at the Center for Reproductive Medicine “Universe” and approved by corresponding Ethics Committee. The aim of the study was explained to all participants in advance and informed consent for participation in the study was signed by all of them.

Each participant, before enrolling in the study received hormonal testing on the second to third day of the menstrual cycle (m/c), to confirm the diagnosis and establish the exclusion of related diseases. Between the 2nd and 3rd day of the m/c, all participants underwent a US examination using voluson E10 (General Electric, Boston, MA). This was done to determine ovarian volume, antral follicle count (AFC) per ovary, and follicle size. Total AFC was defined as the sum of the number of follicles in both ovaries. We prioritized intravaginal examinations, but for virgin patients we used abdominal examinations. Data was analyzed using the statistical analysis programs SPSS version 24.0.

Results

AFC was significantly higher in PCOS patients (33.25±2.4) than in controls (17.49± 2.9; p<0.001). There was no significant difference in average ovarian volume between PCOS patients (14.65± 5.1 cm3) and controls (12.97± 3.9 cm3). Mean follicle size in adolescents with PCOS (6.2± 1.6 mm) and without PCOS (7.7±2.5 mm) did not differ significantly (Table 1).

Discussion

In our study we didn’t find a statistically significant difference of ovarian volume and follicle size in adolescents with and without PCOS, but in PCOS patients, the number of antral follicles were significantly higher than in controls. Some sources didn’t reveal the difference between PCOS adolescents and control group in volume of ovaries and AFC, mean follicle size [6]. However, there are studies, which show higher ovarian volume in PCOS patients, compared with healthy adolescents [2]. Only in few studies, like in our study, the difference in AFC was detected [5,6]. This emphasized that diagnostic criteria for PCOS which include ovarian morphology may have limited use in adolescence, because the data is inadequate, that peak ovarian maturity has not been reached yet, and that defining polycystic ovary morphology at this life stage is not possible. From a practical point of view, for early diagnosis of PCOS in adolescents, besides ultrasound investigation it’s important to use all other diagnostic markers. To sum up, for the diagnosis of PCOS in adolescents, besides the traditional diagnostic criteria, searching for new markers is very important, particularly the determination of the possibility of using AMH for the diagnosis and management of PCOS [7,8]. Thus, further investigations and data collection in this direction should be considered reasonable and highly important.

Conclusion

According to the results of this study ultrasound estimation of Antral follicle count (AFC) is a more specific marker of Ovarian Morphology in Adolescents with PCOS, than ovary volume and mean follicle size.

References

- Rosenfield R (2013) Clinical review: Adolescent anovulation: maturational mechanisms and implications J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98(9): 3572-3583.

- Mortensen M, Rosenfield RL, Littlejohn EJ (2006) Functional significance of polycystic-size ovaries in healthy adolescents. Clin Endocrinol Metab91(10): 3786-3790.

- Rotterdam ESHRE/ASRM-sponsored PCOS consensus workshop group. (2004) Revised 2003 consensus on diagnostic criteria and long-term health risks related to polycystic ovary syndrome.Fertil Steril 81(1): 19-25.

- Carmina E, Rosato F, Janni A, Rizzo M, Longo RA (2006) Extensive clinical experience: relative prevalence of different androgen excess disorders in 950 women referred because of clinical hyperandrogenism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab91 (1): 2-6.

- Witchel S, Oberfield S, Rosenfield R, Codner E, Bonny A, et al. (2015) The Diagnosis of Polycystic Ovary Syndrome during Adolescence. Horm Res Paediatr 83: 376-389.

- Brown M,Park A,Shayya R, Wolfson T, Su HI, et al. (2013) Ovarian Imaging by Magnetic Resonance in Adolescent Girls with Polycystic Ovary Syndrome and Age-Matched Controls. J Magn Reson Imaging38(3): 689-693.

- Elene Asanidze, Jenaro Kristesashvili, Lali Pkhaladze and Archil Khomasuridze (2019) The value of anti-Mullerian hormone in the management of polycystic ovary syndrome in adolescents. Gynecological Endocrinology 22:1-4.

- Sopher A, Grigoriev G, Laura D, Cameo T, Lerner JP, et al. (2014) Anti-Mullerian hormone may be a useful adjunct in the diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome in nonobese adolescents. J. Pediatr Endocrinol Metab27(11-12): 1175-1179.