Primary Hyperaldosteronism as one of the most common forms of Secondary Arterial Hypertension- Clinical Case

O V Tsygankova1,2*, T I Batluk1, L D Latyntseva1 and E V Akhmerova3

1Research Institute of Internal and Preventive Medicine – Branch of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Science, Russia

2 Ministry of Health of Russia, Novosibirsk State Medical University, Russia

3 Novosibirsk City Clinical Polyclinic N16, City Endocrinology Center, Russia

Submission: June 10, 2019; Published: June 21, 2019

*Corresponding author:Oksana V Tsygankova, Department of Emergency Therapy with Endocrinology and Occupational Pathology, Institute of Internal and Preventive Medicine – Branch of the Institute of Cytology and Genetics, Siberian Branch of Russian Academy of Science, Laboratory of clinical, bioc

How to cite this article:O V Tsygankova, T I Batluk, L D Latyntseva, E V Akhmerova. Primary Hyperaldosteronism as one of the most common forms of Secondary Arterial Hypertension- Clinical Case. J Endocrinol Thyroid Res. 2019; 4(4): 555645. DOI: 10.19080/JETR.2019.04.555645

Abstract

Primary hyperaldosteronism is a common cause of hypertension. Its prevalence reaches 15% among the forms of arterial hypertension. Prolonged exposure to elevated aldosterone concentrations is associated with target organ damage in the heart, kidney, arterial wall, and high cardiovascular risk in patients with primary hyperaldosteronism. However, the lack of attention to this problem persists among doctors of various specialties, especially general practitioners. Timely diagnosis and treatment of these patients depends on the correct choice of screening and clarifying diagnostic methods. A long ten-year diagnostic way to identify primary hyperaldosteronism in a young person with refractory hypertension is described below.

Keywords: Refractory hypertension; Primary hyperaldosteronism; Adrenal adenoma; Clinical case

Introduction

Primary hyperaldosteronism (PHA) is one of the most common forms of secondary hypertension; PHA accounts for 5–15% of cases [1]. Although it was mistakenly thought that the disease was a rare pathology. Recently, the concept of laboratory symptoms has changed, since hypokalemia isn’t a basic diagnostic criterion, which is detected only in 9–37% of patients [2-4]. To date, despite the availability of screening, detectability and accordingly the appointment of specific approaches to the treatment of PHA remain low [5]. Separately, it is necessary to emphasize the lack of awareness of the medical community about the problem of PHA [6]. An important clinical argument for more thorough identification and adequate treatment of PHA is undoubtedly an increased risk of complications associated with a specific lesion of target organs: myocardium, kidneys, and blood vessels [7]. There is a significant deterioration of the cardiovascular prognosis in patients with PHA (ischemic stroke, myocardial infarction, atrial fibrillation, heart failure). The following is a clinical case of PHA in a patient with refractory hypertension, normokalaemia and the absence of biochemical abnormalities in the early stages of observation, which complicates timely diagnosis.

Case Report

Patient D., 44 years old, was admitted to the clinic of the Research Institute of Therapy and Preventive Medicine of the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Novosibirsk in November 2018 with complaints of blood pressure instability, anxiety and palpitations during blood pressure elevation, episodes of dizziness, weakness, and night cramps in the calf muscles. The patient also noted swelling of both legs, which did not depend on the time of day and did not decrease during the night’s sleep. She had a hypertensive history since 2005, with a maximum rise in blood pressure up to 245/170 mmHg and constantly takes Candesartan 32 mg/day, Bisoprolol 5 mg/day, Hydrochlorothiazide 25 mg/day, Doxazosin 6 mg/day. Despite medication intake, blood pressure is 160-180/110-120 mm Hg. Calcium antagonists’ therapy was categorically denied by the patient due to the development of marked lower limb edema in the past. According to an outpatient card, 2-3 times a month suffers sympatho-adrenal crises, accompanied by headaches, palpitations, a feeling of internal tremor, numbness and paresthesias in the extremities. A bad effect on standard antihypertensive therapy is detected (decrease in blood pressure only 2 hours after the crisis and no more than 30%).

In 2008, the formation of the right adrenal 24x17x17 mm was found, the radiological semiotics data didn’t indicate its malignant character. In terms of the diagnostic search, despite the need for the primary exclusion of hyperaldosteronism as the most common cause of hypertension in patients with adrenal incidentaloma, twice (in 2010 and 2014) a hormonal examination for pheochromocytoma was performed. Daily urine metanephrine/normetanephrine levels were within the reference range. Hypercortisolism in the terms of the standard examination protocol of the patient with the adrenal gland mass wasn’t carried out.

In 2013, the aldosterone / renin ratio was already 184 pg / μMED, in April 2017 - 300 pg / μMED (N<12 pg / μMED). It, together with persistent low potassium levels, highly normal sodium concentration, clinical symptoms (heartbeat, weakness, convulsions, refractory hypertension) should initiated diagnostic tests confirming the diagnosis of primary hyperaldosteronism (PHA) - test with saline, captopril, fludrocortisone, oral sodium load, but this was not carried out later. The therapy recommended by endocrinologists and cardiologists with Spironolactone as a drug for the treatment of refractory hypertension doesn’t take the patient on a regular basis.

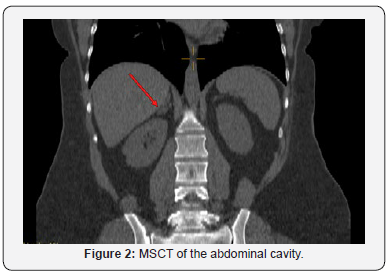

Despite an incomplete examination of the presence and level of hormonal activity of the adrenal gland adenoma, in 2014 the patient was consulted by a surgeon - surgical treatment was not recommended. Subsequently, the frequency of MSCT studies with contrasting was every 1-2 years, the last visualization was carried out in April 2018 (Figures 1 & 2). In the dynamics over 4 years, the size of the formation practically didn’t demonstrate any dynamics. MRI scan of the brain in 2008 revealed no pathology. There are some comorbidities - Autoimmune thyroiditis, diffuse form, goiter 0, Primary subclinical hypothyroidism (takes L-thyroxine 50 μg), thyroid stimulating hormone (November 2017) is 3.8 mIU / ml. There is an atherosclerotic plaque in the right internal carotid artery with minor stenosis (NASCET). The patient has been taking Jess drugs for contraception since 2016. She has two healthy children; she had no operations or fractures.

On physical examination, the patient’s condition is satisfactory, moderate diffuse hyperhidrosis, pale pink stria on the lateral surfaces of the abdomen. The distribution of adipose tissue is uniform, a BMI of 40.12 kg / m2. Heart sounds are clear, rhythmic, heart rate is 63 per minute, blood pressure on the right hand is 163/105 mmHg, blood pressure on the left hand is 160/102 mmHg. There is vesicular breathing, wheezing is absent. Respiratory rate is 17 min. The abdomen is soft, enlarged due to subcutaneous fat, painless. There is swelling of the feet and lower third of the leg on both sides. Physiological functions are normal. O2 saturation alone - 97%. No night snoring. On routine investigations, blood test, urine test, kidney and thyroid function tests were within normal limits. Blood glucose was 6,6 mmol/l. Low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL cholesterol) was 3.8 mmol / l, high-density lipoprotein cholesterol - 0.8 mmol/l, triglycerides - 3.3 mmol / l. Glycated hemoglobin - 6.1%. Hemostasis - mild hyper aggregation, normal coagulation.

ECG - sinus rhythm, heart rate - 65 per minute, the electrical axis of the heart is rejected to the left, signs of left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH). Night computer pulsoximetry revealed no evidence of saturation disturbance (mean saturation of 97%). EchoCG: Aortic diameter 3.4 cm. Left atrium diameter 3.9 cm, LV LVDR 4.6 cm, LV LVC 3.0 cm. The LV ejection fraction from the apical access is 70%. Interventricular septum thickness 1.2 cm, LV posterior wall thickness 1.14 cm. Right ventricle: diameter 2.8 cm. LV myocardium mass 161 g. Sclerosis of aortic root, ascending aorta. Minor sclerosis of the mitral ring, mitral regurgitation 1 degree. LV hypertrophy of moderate severity. Minor diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle, without disturbing the global systolic function. Local areas of myocardial contractility abnormality were not detected. The post infusion level of aldosterone in the patient was 189 pg / ml, which made it possible to verify the diagnosis (it is considered highly reliable for aldosteronemia more than 100 pg / ml); In addition, the electrolyte changes identified after the infusion — a significant decrease in potassium and a slight increase in sodium also testified in favor of PHA.

Based on complaints, anamnesis, clinical picture, data from laboratory and instrumental methods of research, results of a diagnostic test, 13 years after the debut of hypertension and 10 years after visualization of the adenoma, a clinical diagnosis was detected: Right adrenal adenoma. Primary hyperaldosteronism. Refractory hypertension of 3 degrees, very high risk. Sympathoadrenal crises. Chronic heart failure I (NYHA). Impaired glucose tolerance. Morbid obesity (BMI 40.2 kg / m2), slowly progressive course. DLP IIb phenotype. Atherosclerotic plaque in the right internal carotid artery with a slight stenosis - 25% (NASCET). AIT, diffuse form. Goiter 0. Primary subclinical hypothyroidism, medical euthyroidism.

The patient was discharged from the hospital in a satisfactory condition on an outpatient stage with recommendations to enrich the food with potassium-containing products (dried apricots, prunes, beans, avocados, pumpkin), continue the previously conducted antihypertensive therapy with the inclusion of Spironolactone 100 mg 2 times / day, followed by dose titration to 300 - 400 mg / day if necessary and Rosuvastatin 20 mg / day (target values of LDL cholesterol <1.8 mmol / l). The prescription of acetylsalicylic acid is not indicated in primary prevention. An outpatient small dexamethasone test is also required (a mandatory minimum of the patient’s diagnostic examination with the formation of the adrenal gland to exclude subclinical or cyclic “cushing”). After normalization of blood pressure and clarifying the level of production of glucocorticoids, a planned laparoscopic adenomectomy or adrenalectomy should be performed.

Discussion and Conclusion

In conclusion, we should note the lack of specific, “marker” symptoms of PHA, which makes it difficult to timely identify and postpones the diagnosis for 5-10 years or more, to the stage of formation of target organ damage or associated clinical conditions, up to severe congestive heart failure. A serious obstacle is also a lack of awareness of therapists and cardiologists about endocrine hypertension and tactics of managing patients with adrenal mass. In their daily practice, doctors of “first contact” should remember about PHA as a frequent cause of endocrine hypertension, unlike, for example, pheochromocytoma, the incidence of which is extremely low, especially in the presence of seizure syndrome, weakness, carbohydrate disorders, edema, hypokalemia or low normal values potassium. The definition of an aldosterone / renin ratio is a test of primary diagnosis and may be recommended by doctors of any therapeutic specialties.

A special group consists of patients with formations in the adrenal glands, which must be followed by the following hormonal examination: 1) determination of aldosterone / renin ratio, 2) analysis of daily urine (or plasma) for metanephrine and normetanephrine, 3) the study of serum cortisol in the morning during the morning small dexamethasone test or analysis of daily urine for free cortisol (double determination) or the study of evening cortisol in saliva (double definition). Levels of sex hormones (estrogens and androgens) are evaluated in the presence of clinical indications. Such an algorithmized approach will allow timely verification of the cause of hypertension, optimize approaches to drug therapy, and when confirming a diagnosis of a hormone-producing adrenal adenoma, consider the possibility of surgical treatment.

References

- Williams B, Mancia G, Spiering W, Agabiti Rosei E, Azizi M, et al. (2018) 2018 ESC/ESH Guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension. European Heart Journal 39(33): 3021-3104.

- Funder JW, Carey RM, Mantero F, Murad MH, Reincke M, et al. (2016) The management of primary aldosteronism: case detection, diagnosis, and treatment: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 101(5): 1889–1916.

- Stowasser M (2015) Update in primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 100(1): 1-10.

- Mulatero P, Monticone S, Bertello C, et al. (2013) Long-term cardio- and cerebrovascular events in patients with primary aldosteronism. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98(12): 4826-4833.

- Nadeeva RA, Kamasheva GR, Yagfarova RR (2015) Primary hyperaldoseronism in the structure of arterial hypertension: actuality of problem. The Bulletin of Contemporary Clinical Medicine 8(6): 98-102.

- Young WF Jr (2018) Diagnosis and treatment of primary aldosteronism: practical clinical perspectives. J Intern Med 285(2): 126-148

- Monticone S, D'Ascenzo F, Moretti C, Williams TA, Veglio F, et al. (2018) Cardiovascular events and target organ damage in primary aldosteronism compared with essential hypertension: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 6(1): 41-50.