Pheochromocytoma/Ganglioneuroma and Auto-Immunity: Report of Two Cases

Fatma Mnif*, Wafa Ben Othmen, Dorra Ghorbel, Mouna Elleuch, Dhouha Ben Salah and Mohamed Abid

Department of endocrinology, CHU Hedi Chaker Sfax, Tunisia

Submission: March 28, 2019; Published: April 26, 2019

*Corresponding author:Fatma Mnif, Department of endocrinology, CHU Hedi Chaker Sfax, Tunisia

How to cite this article:Fatma M, Wafa B O, Dorra G, Mouna E, Dhouha B S, et al. Pheochromocytoma/Ganglioneuroma and Auto-Immunity: Report of Two Cases. J Endocrinol Thyroid Res. 2019; 4(3): 555636. DOI: 10.19080/JETR.2019.04.555636

Introduction

Both pheochromocytoma and ganglioneuroma (GN) are tumors of neural crest origin [1]. While pheochromocytoma originates from the adrenal medullary chromaffin cells, GN represents a tumor from autonomic ganglion cells or their precursors [2]. Only a small proportion of ganglioneuromas is of adrenal origin [3]. We report two cases of rare associations between an adrenal GN and a pheochromocytoma and auto-immune endocrinopathies: Addison’s disease and Hashimoto’s disease respectively.

Case 1

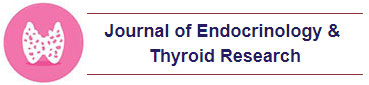

A 24-year-old female came with an ascites of great abundance and transudative character in fine-needle aspiration cytology (protein=51g/l, white blood cells=60/mm 3, lymphocytes=65%) whose etiologic investigation was negative, namely the research of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in the urine and in the spittle, liver serology (hepatitis A, hepatitis B, hepatitis C and hepatitis E serology), serologic tests for autoimmune hepatitis (anti LKM1 - anti smooth muscle - anti mitochondria) and tumor markers. The evolution was marked by the persistence of an ascites blade of low abundance after drainage. During the investigation of this disease, a heterogeneous, hypoechogenic right adrenal solid mass, measuring 51x33 mm, was incidentally detected through abdominal CT scan. The patient was referred to our department for further examination. Blood pressure was normal (110/70 mmHg). Physical examination demonstrated no significant finding. Routine laboratory tests were normal. Endocrine tests (Table 1), including Plasma Aldosterone Concentration (PAC), Plasma Rennin Activity (PRA), PAC/PRA ratio, diurnal cortisol rhythms, 24-h urinary catecholamines, and their metabolites were within normal ranges.

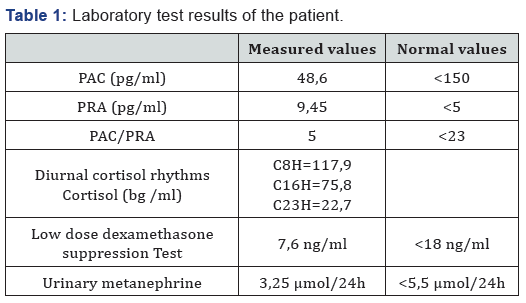

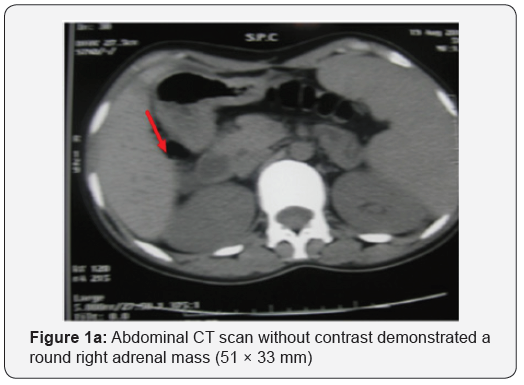

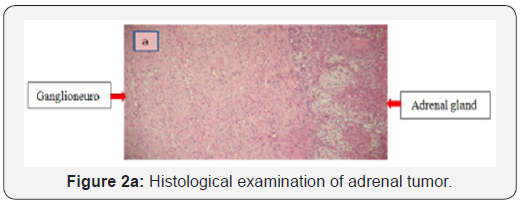

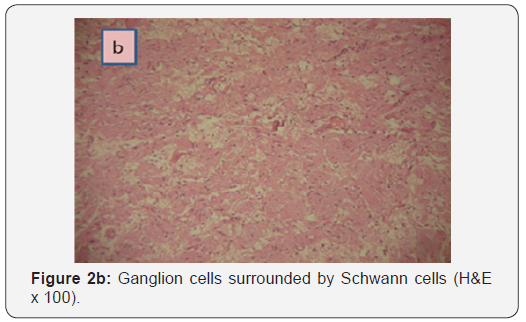

Abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed a round right adrenal mass of irregular outline, having a diameter of 51x33 mm and its spontaneous density was 36UH with heterogeneous contrast enhancement and without calcification. (Figures 1a and b), the left adrenal gland was normal. Magnetic resonance imaging was not performed. Right Laparoscopic adrenalectomy was performed through the transabdominal route under general anesthesia. The removed tumor was well circumscribed, measuring 60 x50 x15 mm. The histological diagnosis was that of adrenal ganglioneuroma by showing mature ganglion cells spindle shaped, called Schwann cells (Figures 2a and b). The immunohistochemical analysis was not performed.

Case 2

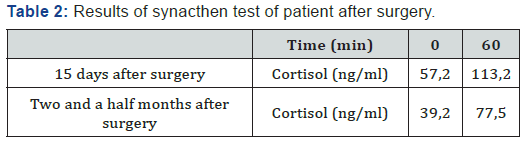

Four days after the operation, the patient experienced nausea, vomiting and abdominal pain with a hypotension of 90/60 mmHg. At first, we had thought of a possible postoperative complication such as deep bruising or abscess of the abdominal wall of the operation site. These two possibilities were eliminated with a normal abdominal ultrasound scan. Clinical examination, however, was strongly in favor of an adrenal failure which could not be explained by the unilateral adrenalectomy of a non-secreting adrenal adenoma. Laboratory tests were normal except for the level of plasma cortisol which was reduced to 57 ng/ml. Adrenal failure was confirmed by two synacthen 250 μg tests which were performed first 15 days and then two and a half months after surgery (Table 2). Besides that, the other hormonal tests were not controlled.

As part of etiological investigation for adrenal failure, adrenal antibodies and 21-hydroxylase antibodies, which are specific markers of the adrenal gland, were strongly positive to 2866.9 U/ ml [1-100 UI/ml], confirming the diagnosis of Addison’s disease associated with adrenal ganglioneuroma. However, our patient hasn’t any other signs of autoimmunity particularly she has not goiters, she has a regular cycle and the rest of the immunological tests including anti TPO tests and anti-thyroglobulin were negatives.

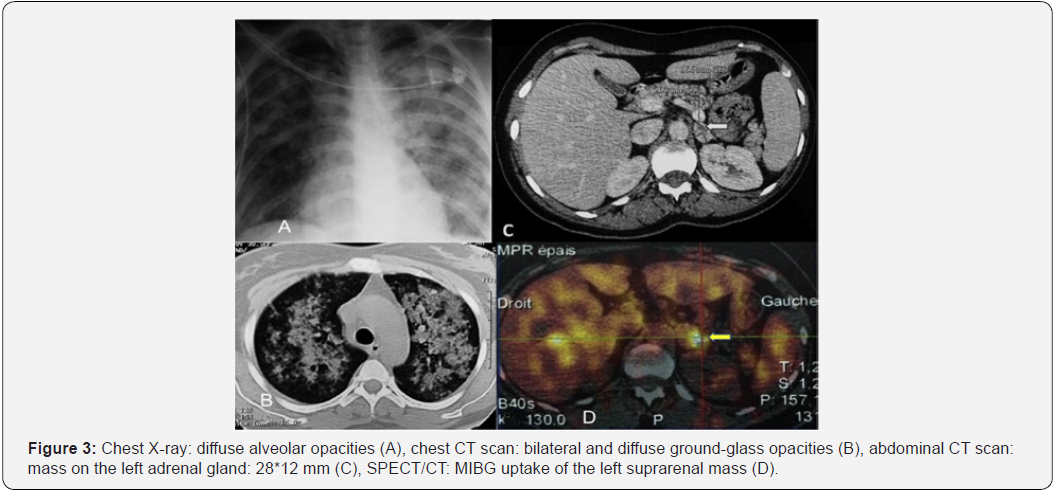

A 39-year-old woman was hospitalized in pneumology department for hemoptysis of medium abundance associated with acute respiratory distress. Chest X-ray revealed diffuse alveolar opacities (Figure 3). The bronchoalveolar lavage found a hyper-cellular macrophage-predominant (87%) hemorrhagic fluid with presence of side rophages, without signs of malignancy. The hemostasis screening tests were normal and there were no biological stigmata of infection. Immunological tests (rheumatoid factor, anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-glomerular basement membrane antibodies, anti-neutrophil cytoplasm antibodies, antiphospholipid antibodies) were negative. The patient was diagnosed with diffuse alveolar hemorrhage. Its etiological assessment was negative.

A chest CT scan revealed on the cuts through the upper abdomen a mass on the left adrenal gland, for which the patient was transferred to our endocrinology department. A detailed questioning revealed that the patient had developed for 3 years paroxysmal symptoms made of headache, pain on the left hypochondrium and profuse sweating without triggering factor. The rest of the endocrine examination showed clinical euthyroidism with a homogeneous palpable thyroid. The thyroid status (TSH = 9.2 mIU / L, FT4 = 12.3pmol / L) was in favor of a subclinical hypothyroidism.

A 24-hour blood pressure monitoring confirmed the hypertension. A 24-hour urinary collection showed elevated levels of catecholamines and metabolites (4 times normal value: 6,51 μmol/24 h (N :0,4–2,10)). An abdominal CT scan focused on adrenal glands showed a mass on the left adrenal gland (measuring 28*12 mm), which had a spontaneous density of 36UH with a discreetly heterogeneous contrast enhancement and an absolute wash-out of 37%.

A whole-body scan using iodine-131 metaiodobenzyl guanidine (131I-MIBG) revealed an evident accumulation of 131I only over the left adrenal gland. Thus, the adrenal tumor was clinically diagnosed as pheochromocytoma. We could not find any sign of an accompanying MEN2a nor MEN2b syndrome. Following a pretreatment with an ɑ-adrenergic blocker, the patient underwent a laparoscopic left adrenalectomy. The diagnosis of pheochromocytoma was confirmed on histological examination with a Pass score of 3. On immunohistochemical analysis, tumor cells were positive for chromogranin and synaptophysin and negative for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). S100 protein marked supra-tentacular cells surrounding the tumor mass. Thirty-three months post-operatively, our patient is symptomfree with blood pressure within the normal range without any medication. The catecholamine and metabolite concentrations in the plasma and urine have been normal. Abdominal CT has demonstrated no abnormal masses.

The patient was diagnosed with diet-controlled type 2 diabetes mellitus two years after surgery with a good glycemic control. In addition, the subclinical hypothyroidism, objectified preoperatively, had evolved into the patent form. Antithioperoxides and anti-thyroglobulin antibodies were positive at 585 and 155 IU / ml, respectively. Thus, the diagnosis of Hashimoto’s disease was established and the treatment with L-thyroxine was administered. The search for other autoimmune diseases was negative except for anti-nuclear antibodies which were positive twice: 1/640 then 1/160without any signs in favor of a systemic disease.

Discussion

Among the neuroblastic tumors, GN is the most uncommon, the one with the greatest histological differentiation, and the most benign. Only 20-30% is of adrenal origin. GNs may occur at any age, but mostly appear under 20 years of age [4].There is a female predominance with a sex ratio of 0,75 [5]. Adrenal GNs are not associated with clinical or biochemical evidence of endocrine hormonal activity [6]. Clinical symptoms of GNs are nonspecific and related to the location site. Despite their generally benign nature, GNs may come to attention by compressing neighboring structures [7]. In fact, any retroperitoneal tumors of a large size are capable of causing a variety of digestive disturbances which may include reactive ascites [8] as in our first case where the discovery of the GN came as a result of the investigation of an ascites of great abundance.

As for the other neuroplastic tumor studied in our second case: Pheochromocytoma, its detection poses an immense clinical challenge as numerous atypical presentations have been reported in the literature such as hemoptysis [9,10]. However, it is rarely linked to a diffuse alveolar hemorrhage which is an exceptional presentation of the pheochromocytoma as demonstrated in our second case. Pathophysiological mechanisms most often involved in hemoptysis are lung metastases and coagulation disorders. When all of these have been ruled out, hemoptysis may be related to the hypertensive crisis triggered by chromaffin tumor secretion. In these cases, the paroxysmal hypertension crises will produce pulmonary vein hypertension causing capillary rupture and the passage of erythrocytes to the alveolar space, resulting in hemoptysis [11].

The association between GNs/pheochromocytoma and autoimmune endocrinopathies is quite rare and not well studied in literature. The association between pheochromocytoma and Addison’s disease or Primary Adrenal Insufficiency (PAI) which is caused by autoimmune destruction of the adrenal cortex was first described in 2008 on an atrophied adrenal gland [12]. However, the association of GN with PAI, has been reported for the first time in our first case [13]. The patient was diagnosed with Addison’s disease after presenting acute adrenal insufficiency symptoms. Prior to surgery, the 8 AM cortisol levels were 117,9ng/ml (322nmol/l): such levels may well be found in preclinical states of PAI. Moreover, the acute adrenal failure was likely precipitated by surgery, adrenalectomy and perhaps also anesthetics. The common autoimmune form of PAI is characterized by the presence of steroid 21-hydroxylase autoantibodies with high specificity (90%) and sensibility (85%) [14,15] and if the test is positive, further etiologic evaluation is not generally necessary; however, other causes should be sought if no autoantibodies are detected.

It is well known that pheochromocytoma is accompanied by medullary thyroid malignancy in MEN syndromes. It has been stated that auto-immune thyroid diseases may also accompany pheochromocytoma. Becker and al. have shown that five out of 36 cases with pheochromocytoma presented with thyroid disease other than medullary carcinoma and in three of these (8,3 %) abnormal thyroid functions were noted [16]. Bartolomei, et al. [17] have pointed out a case with pheochromocytoma accompanying autoimmune hypothyroidism. Pheochromocytoma was shown to accompany not only hypothyroidism but also hyperthyroidism and goiter [18-20]. Thyroid gland swelling with a subsequent diagnosis of pheochromocytoma was first reported in 1947 [21], followed by other studies. The thyroid gland is enlarged in 6% of the cases with pheochromocytoma. It has been shown that experimental infusion of norepinephrine may induce such enlargement [22,23]. Its mechanism and its action on human goiter have not yet been clarified.

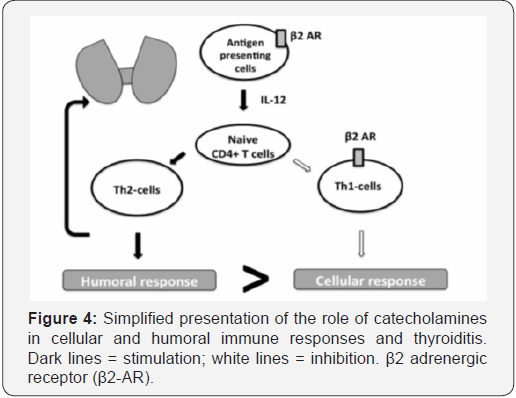

Some authors suggested the existence of functional interactions between thyroid hormones, catecholamine receptors, and the immune system. The hypothesis postulating interrelation between the sympathetic system and thyroid hormones by means of the α- and β- adrenergic receptors (ARs) has been formulated [24]. We may suppose that excessive production of catecholamines as in our second case could induce thyroiditis via immune dysregulation. Indeed, changes in peripheral lymphocyte subsets, with an increase in CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, have been observed in patients with active subacute thyroiditis [25]. Action of catecholamines is likely to be mediated via β2-ARs located on the antigen presenting cells and T helper 1 (Th1) cells [26]. Activation of the β2-ARs leads to inhibition of the cellular immune response and activation of T helper 2 (Th2) cell–mediated humoral immunity, thus disrupting the Th1/ Th2 balance (Figure 4). Th1 cytokines, such as interferon-c (INFc), and Th1-inducing cytokines, such as IL-12, are involved in the pathogenesis of various organ-specific autoimmune diseases [27,28].

Conclusion

concomitant auto-immune endocrinopathies should be considered in the context of both adrenal GN and pheochromocytoma. In addition, these tumors may present atypical and non-specific symptomatology. Our two cases underline these particularities. Further research and new molecular and genetic investigations are needed to fully understand the pathology of GN and pheochromocytoma and their association with auto-immune endocrinopathies, Addison’s disease and Hashimoto’s disease.

References

- Greer M, Anton AH, WillIams CM, Echevarria RA (1965) Tumors of neural crest origin: Biochemical and pathological correlation. Arch Neurol 13: 139-148.

- Rao R, Singla N, Yadav K (2013) Composite pheochromocytoma-ganglioneuroma of the adrenal gland: A case report with immunohistochemical study. Urol Ann 5: 115-

- Martínez F, Delgado M, González B, Cosano A, Armada R, et al. (2003) Ganglioneuroma suprarrenal. aportación de un nuevo caso. Actas Urol Esp 27: 221-225.

- Alramadan M, et al. (2013) Ganglioneuroma suprarrenal: un reto diagnóstico. Endocrinol Nutr 60: 272-273.

- Hafiani M, Rabii R, Debbagh A, Rais H, Bennani S, et al. (1998) Retroperitoneal ganglioneuroma. Apropos of a case. Ann Urol (Paris) 32: 20-22.

- Bin X, Qing Y, Linhui W, Li G, Yinghao S (2011) Adrenal incidentalomas: experience from a retrospective study in a Chinese population. Urol Oncol 29: 270-274.

- Koch CA, Brouwers FM, Rosenblatt K, Burman KD, Davis MM, et al. (2003) Adrenal ganglioneuroma in a patient presenting with severe hypertension and diarrhea. Endocr Relat Cancer 10: 99-107.

- McCarthy S, Duray PH (1983) Giant retroperitoneal neurilemoma: a rare cause of digestive tract symptoms. J Clin Gastroenterol 5(4): 343-347.

- Dolan RT, Butler JS, Mentee GP, Byrne M (2011) Pheochromocytoma presenting as recurrent urinary tract infections : A case report. J Med Case Reports 5: 6.

- Kimura Y, Ozawa H, Igarashi M, Iwamoto T, Nishiya K, et al. (2005) A pheochromocytoma causing limited coagulopathy with hemoptysis. Tokai J Exp Clin Med 30(1): 35-39.

- Querol Ripoll R, del Olmo García MI, Cámara Gómez R, Merino-Torres JF (2014) Diffuse Alveolar Hemorrhage as First Manifestation of a Pheochromocytoma. Arch Bronconeumol 50(9): 412-413.

- Toni García M, Anda Apiñániz E, Pablo J, de Esteban M, Munárriz Alcuaz P, et al. (2008) An unusual association: pheochromocytoma on an atrophied adrenal gland due to addison’s disease. Endocrinol Nutr 55(10): 510-513.

- Mnif F, Graja S, Mnif MF, Bouaziz Z, Kammoun M, et al. (2015) Association of Adrenal Ganglioneuroma with Addison’s Disease: A Case Study. J Clin Stud Med Case Rep 2: 022.

- Tanaka H, Perez MS, Powell M, Sanders JF, Sawicka J, et al. (1997) Steroid 21-Hydroxylase Autoantibodies: Measurements with a New Immunoprecipitation Assay. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 82(5): 1440-1446.

- Laureti S, De Bellis A, Muccitelli VI, Calcinaro F, Bizzarro A, et al. (1998) Levels of Adrenocortical Autoantibodies Correlate with the Degree of Adrenal Dysfunction in Subjects with Preclinical Addison’s Disease . J Clin Endocrinol Metab 83 (10): 3507-3511.

- Becker CE, Rosen SW, Engelman K (1969) Pheochromocytoma and Hyporesponsiveness to Thyrotrophin in a 46 XY Male with Features of the Turner Phenotype. Ann Intern Med 70: 325-33.

- Bartolomei C, Gianchecchi D, Chiavistelli P, Lenzi R (1992) Pheochromocytoma and autoimmune hypothyroidism. Minerva Med 83(7-8): 485-486.

- Braverman LE, Sullivan RM (1969) Another polyendocrine disorder: pheochromocytoma and diffuse toxic goiter. Johns Hopkins Med J 125(6): 331-335.

- Dimova MN, Kiscleva TP (1987) Case of combined diffııse toxic goiter and plıeochromocytoma. Probl Endokrinol Mosk 33: 42-43.

- Snow MH, Burton P (1976) A case of associated thyrotoxicosis and phaeochromocytoma. A diagnositc problem. Postgrad Med J 52(607): 288-291.

- Bauer J, Belt E (1947) Paroxysmal hypertension with concomitant swelling of the thyroid due to pheochromocytoma of the right adrenal gland; cure by surgical removal of the pheochromocytoma. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 7(1): 30-46.

- Hcrman H, Momex R (1964) Human Tumours Secrcling Catecholamines. In: Pergamon Press, US.

- Paschke R, Enger I, Harsch I, Usadel KH (1992) Relapse of Graves’ disease following development of a pheochromocytoma. Thyroid 293): 203-206.

- Silva JE, Bianco SD (2008) Thyroid–adrenergic interactions: physiological and clinical implications. Thyroid 18(2): 157-165.

- Iwatani Y, Amino N, Hidaka Y, Kaneda T, Ichihara K, et al. (1992) Decreases in alpha beta T cell receptor negative T cells and CD8 cells, and an increase in CD4+ CD8+ cells in active Hashimoto's disease and subacute thyroiditis. Clin Exp Immunol 87(3): 444-449.

- Panina-Bordignon P, Mazzeo D, Lucia PD, D’Ambrosio D, Lang R, et al. (1997) Beta2-agonists prevent Th1 development by selective inhibition of interleukin 12. J Clin Invest 100(6): 1513-1519.

- Schranz DB, Lernmark A (1998) Immunology in diabetes: an update. Diabetes Metab Rev 14(1): 3-29.

- Furmaniuk A, Demarquet L, Klein M, Weryha G, Feigerlova E (2016) Subacute Thyroiditis Revealing a Pheochromocytoma. AACE Clin Case Reports 2: 161-166.