Glycemic Control and Sleep Quality Response to Life Style Modification among Obese Type 2 Diabetic Patients

Mohammed H Saiem Al-Dahr*

Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, Saudi Arabia.

Submission: April 14, 2018; Published: May 08, 2018

*Corresponding author: Mohammed H Saiem Al-Dahr, Department of Medical Laboratory Technology, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, King Abdulaziz University, P.O. Box 80324, Jeddah, 21589, Saudi Arabia, Email: mdahr@kau.edu.sa

How to cite this article: Mohammed H S A-D. Glycemic Control and Sleep Quality Response to Life Style Modification among Obese Type 2 Diabetic Patients. J Endocrinol Thyroid Res . 2018; 3(3): 555615. DOI: 10.19080/JETR.2018.03.555615

Abstract

Background: Recently attention is directed to the potentially negative reinforcing relationships that may exist between sleep disturbance, obesity and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) as good sleep quality is crucial for maintaining an effective glycemic control and improving the quality of life of patients with diabetes.

Objective: The aim of the study was to investigate the effects of weight reduction via life style intervention on glycemic control and sleep quality among obese type 2 diabetic patients.

Material and methods: Eighty obese T2DM patients (43 males and 37 females) with body mass index (BMI) ranged from 30 to 36Kg/m2, their age ranged from 42-56 years were selected from the outpatient diabetic clinic of the King Abdulaziz Teaching Hospital were randomly assigned to life style intervention group (group A, n=40) or control group (group B, n=40). Polysomnographic recordings for sleep quality assessment, body mass index (BMI), the quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index (QUICKI), homeostasis model assessment-insulin resistance index (HOMA-IR), glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were measured before and after 6 months at the end of the study.

Results: There was a significant increase in the mean value of total sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep onset latency and QUICKI in group (A) after 6 months of aerobic exercise training, while, awake time after sleep onset, rapid eye movements (REM) latency, BMI, HOMA-IR) and glycosylated hemoglobin (HBAlc significantly reduced after 6 months of life style intervention, however the results of the control group were not significant. Moreover, there were significant differences between both groups at the end of the study.

Conclusion: Life style intervention is an effective modality for modifying glycemic control and sleep quality among obese type 2 diabetic patients.

Keywords: Glycemic control; Sleep quality; Life style intervention; Obesity; Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Introduction

Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) prevalence has been rising steadily over the past 3 decades, and is largely attributable to the dramatic increase in obesity rate [1,2]. Over 300 million people worldwide live with diabetes now, and if the current prevalence rate continues unabated, over 550 million people will be living with diabetes by 2030 [3,4]. Diabetes represents a major health problem because of its high prevalence, morbidity and mortality, its influence on patient quality of life, and its impact on the health system [5-7].

The quality of sleep is relevant to the regulation of energy and glucose homeostasis [8]. Type 2 diabetes mellitus is a serious chronic disease whereby the body ineffectively use glucose as a fuel due to relative insulin deficiency caused by insulin resistance [9]. Impairments in the daily sleep/wake cycle due to sleep disturbances, including shift working, obstructive sleep apnea, and insomnia, are known to increase the risk of T2DM [10]. Tang and colleagues reported insufficient sleep quality and quantity as a risk factor of developing T2DM and poor glycemic control among sufferers [11]. Sleep duration has also been associated with higher risk of developing T2DM as well representing a strong predictor of glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), with sleep loss being associated with increased HbA1c [12]. The Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) factor "sleep efficiency” is one of the components that can influence glycemic control [13]. A previously published study suggests negative correlation between HbAlc and sleep efficiency [14].

The strong association between obesity and sleep disorders and disturbances is in line with past research regarding the negative impact of excess weight [15-17]. Obesity, a disease associated with its own litany of health consequences and symptomatology, has been independently associated with an increased risk of sleep disorders, disruptions and poor sleep quality [15]. For example, excess weight is a strong predictor of daytime sleepiness and sleep-disorders [17].

A number of epidemiological studies describe a connection between T2DM, and sleep disorders [18]. Studies suggest that a high proportion of T2DM sufferers also manage comorbid sleep apnea, particularly males and those overweight. Estimates from recent studies range from 18% to 36%, suggesting the importance of addressing sleep disorders among this patient group [19-21]. A large-scale survey study found that sleep problems were by up to 40% of individuals with T2DM, with sleep apnea, and restless legs symptoms the most likely among sufferers [22]. Individuals with T2DM who are obese also frequently report sleep problems, with research suggesting that all three may represent a complex interwoven triad of conditions [23,24].

The aim of the study was to investigate the effects of weight reduction via life style intervention on glycemic control and sleep quality among obese type 2 diabetic patients.

Patients and Methods

Subjects

Eighty obese T2DM patients (43 males and 37 females) with body mass index (BMI) ranged from 30 to 36Kg/m2, were selected from the outpatient diabetic clinic of the King Abdalziz Teaching Hospital. They were checked for fasting/random glucose levels. Only participants have fasting blood sugar levels more than 5.6mmol/l or random blood sugar level more than 7.8mmol/l (impaired blood sugar) were included in this study and were further checked for type 2 diabetes mellitus as per recent American Diabetes Association criteria i.e. fasting blood sugar ≥7.0mmol/l or post-prandial blood sugar ≥11.1 mmol/l (2h plasma glucose 11.1 mmol/l during an oral glucose tolerance test) and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c%) > 6.5% [25]. Exclusion criteria included history of major psychiatric disorder as mania or alcohol or substance abuse or other neurological disorders, significant depressive symptoms, kidney insufficiency, congestive heart failure, pregnant female patients, hepatitis and respiratory failure, current use or use within the past month of psychoactive, hypnotic, stimulant or analgesic medications, shift work or other types of self-imposed irregular sleep schedules, smoking or caffeine consumption greater than 300mg per day. A detail clinical history and physical examinations were conducted which included the age, sex, symptoms suggestive of diabetes and family history of diabetes. Physical examinations included anthropometric measurements such as height, weight, body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference. Participants were included two groups; group (A) received treadmill aerobic exercise training on treadmill and diet regimen. However, group (B) was considered as a control group and received no exercise training or diet regimen. A cardiologist conducted an initial clinical examination for all participants and participants were randomized for a weight reduction group (group A) or control group (group B). This study was approved by the Ethical Committee for Scientific Research, Faculty of Applied Medical Sciences, King Abdulaziz University. All participants provided written informed consent.

Measurements

Sleep measures: All participants underwent polysomnographic (PSG) recording before and after the exercise training. For the pre-intervention assessment, PSG recording was performed over 2 nights. The first night served as an adaption night; 48 hour later, the participants returned for another night of PSG recording. The post-training PSG assessment occurred at least 30 hours after the last exercise session. The participants arrived at the sleep laboratory at 21:00; the PSG recording started and finished according to each volunteer's habitual sleep schedule. The room used for the recordings had a large comfortable bed, acoustic isolation, and controlled temperature and light. A trained sleep technician using a digital system (Philips-Respironics, USA) conducted recordings. The following parameters were analyzed:

I. Total sleep time (in min), defined as the actual time spent asleep;

II. Sleep latency (in min), defined as the time from lights out until the onset of three consecutive epochs of stage 1 or deeper sleep;

III. Sleep efficiency, defined as the percentage of total recording time spent asleep;

IV. Wake after sleep onset (in min), defined as the total time scored as wakefulness between sleep onset and final awakening;

V. Sleep stages 1, 2, 3, and 4 as well as REM sleep as percentages of total sleep time; and

VI. Latency to REM, defined as the time from sleep onset until the first epoch of REM sleep [26].

Chemical analysis: Blood samples were collected from the antecubital vein at the beginning and end of the treatment program. Subjects had blood drawn at the same time in the morning on each occasion (between 8 and 10AM). Subjects lay supine for 10 min prior to the blood collection. 10ml of blood was drawn into a tube containing few milliliters of sodium citrate; plasma was separated from the blood by centrifugation (120-x g for 15min) at room temperature to determine level of glycosylated hemoglobin (HBA1c). However, human insulin was measured with an insulin kit (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) using a cobas immunoassay analyzer (Roche Diagnostics). Insulin resistance was assessed by homeostasis model assessment (HOMA-IR). HOMA-IR = [fasting blood glucose (mmol/l) _ fasting insulin (mlU/ml)]/22.5 [27]. However, insulin sensitivity was assessed by The quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index (QUICKI) using the formula: QUlCKl=1/(log(insulin) + log(glucose)) [28]. All samples were assayed in duplicate, and the mean of the paired results was determined.

Measurement of anthropometric parameters: Body weight of all participants was measured with (HC4211, Cas Korea, South Korea) while wearing hospital gowns and undergarments. Where the height was measured with a digital stadiometer (JENIX DS 102, Dongsang), so Body Mass Index (BMI) was computed as BMI= Body weight/Height2.

Procedures

Following the previous evaluation, all patients were divided randomly into the following groups:

Patients in group (A): Were submitted to forty minutes moderate intensity aerobic exercise sessions on a treadmill (the initial, 5-minute warm-up phase performed on the treadmill (Enraf Nonium, Model display panel Standard, NR 1475.801, Holland) at a low load, each training session lasted 30 minutes and ended with 5-minute recovery and relaxation phase) either walking or running, based on heart rate, until the target heart rate was reached, according to American College of Sport Medicine guidelines [29]. The program begun with 10min of stretching and was conducted using the maximal heart rate index (HRmax) estimated by 220-age. First 2 months = 60-70% of HRmax second 4 months = 70-80% of HRmax . Each session was continued for 30 minutes; 3 sessions / week for 3 months [30]. All subjects of group (A) were instructed to take an individual balanced energy-restricted dietary program to obtain weight loss .The mean daily caloric intake was about 1200kcal/day, based on a macronutrient content <30% fat and 15% protein as recommended by the World Health Organization [31]. At the initial interview with a dietitian, obese subjects was given verbal and written instructions on how to keep diet records, with food weighed and measured. The same dietitian monitored dietary intake. The subjects maintained a detailed record of food intake, and received weekly nutritional counseling. Obese subjects were instructed to substitute low-fat alternatives for typical high-fat foods, to increase the consumption of vegetables and fresh fruits, and to substitute complex carbohydrates, such as whole-grain bread and cereals. Dietetic help was given every 2 weeks by the dietitian when anthropometric measurements were performed; in addition, each subject was seen by a physician monthly to perform a clinical evaluation, standard electrocardiogram, and measurement of blood pressure and heart rate [32].

Patients in group (B): Received no training or diet regimen for three months.

Statistical analysis

The mean values of the investigated parameters obtained before and after six months in both groups were compared, using paired "t” test. Independent "t” test was used for the comparison between the two groups (P<0.05).

Results

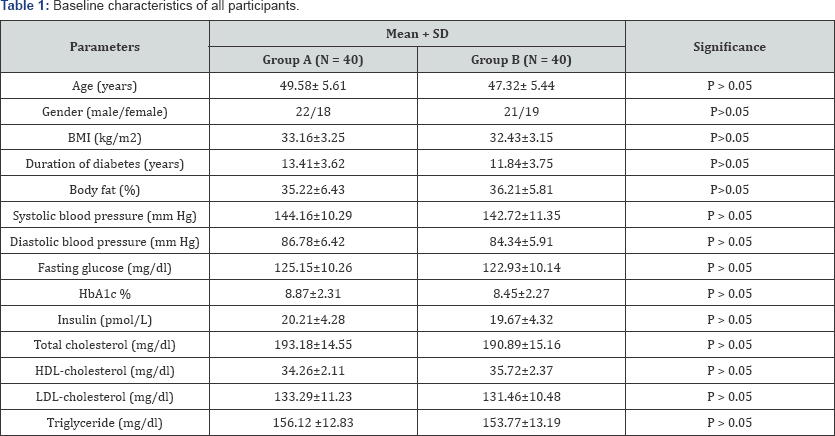

The two groups were considered homogeneous regarding the demographic variables. The mean age of the group (A) was 49.58±5.61 years, and the mean age of group (B) was 47.32±5.44 years. There was no significant differences in age, body mass index (BMI), duration of diabetes, body fat, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, fasting glucose, hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c), serum insulin and blood lipids between both groups (Table 1).

BMI = Body Mass Index; HbA1c = Glycosylated Hemoglobin; HDL= High Density Lipoprotein; LDL= Low Density Lipoprotein

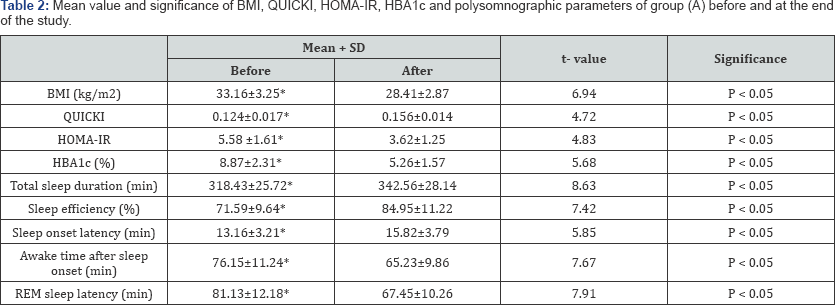

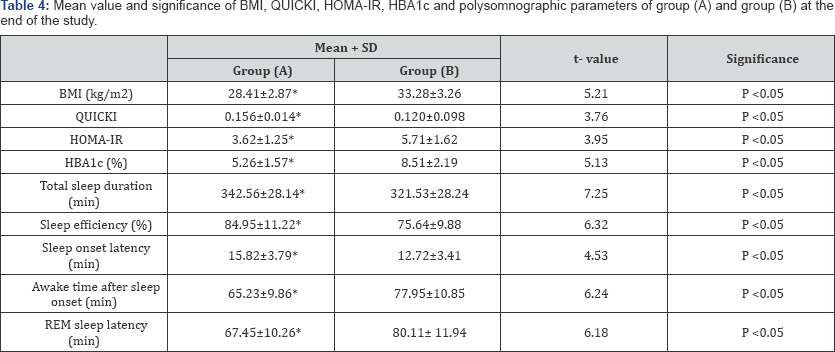

BMI: Body Mass Index; QUICKI: The quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index; HOMA-IR: Homeostasis Model Assessment-Insulin Resistance Index; HbA1c = Glycosylated Hemoglobin; REM: rapid eye movements; (*) indicates a significant difference, P < 0.05.

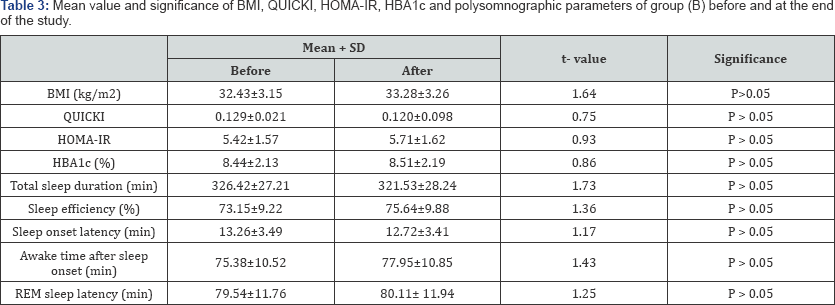

BMI: Body Mass Index; QUICKI: The quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index; HOMA-IR: Homeostasis Model Assessment-Insulin Resistance Index; HbA1c = Glycosylated Hemoglobin; REM: rapid eye movements.

BMI: Body Mass Index; QUICKI: The quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index; HOMA-IR: Homeostasis Model Assessment-Insulin Resistance Index; HbA1c = Glycosylated Hemoglobin; REM: rapid eye movements; (*) indicates a significant difference between the two groups, P < 0.05.

There was a significant increase in the mean value of total sleep duration, sleep efficiency, sleep onset latency and the quantitative insulin-sensitivity check index (QUICKI) in group (A) after 6 months of aerobic exercise training, while, awake time after sleep onset, rapid eye movements (REM) latency, body mass index (BMI), Homeostasis Model Assessment-Insulin Resistance Index(HOMA-IR) and glycosylated hemoglobin (HBAlc) significantly reduced after 6 months of life style intervention (Table 2), however the results of the control group were not significant (Table 3). In addition, there were significant differences between both groups at the end of the study (Table 4).

Discussion

The prevalence of sleep disturbances and deprivation has been increasing dramatically over the past decade, together with the growing epidemic of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) and obesity worldwide. Several meta-analyses have confirmed the independent association between sleep duration and sleep quality with the risk of developing T2DM [33,34], However, Gupta and colleagues reported that about 25% of patients with T2DM were diagnosed with sleep disorders (SD) and over 75% reported experiencing at least one sleep symptom regularly, where SD and symptoms were strongly associated with obesity [35]. Recent epidemiological studies have suggested that there is an association between glycemic control and sleep disturbances in patients with T2DM [36], therefore effective weight management treatment in T2DM patient implemented in the primary care setting [37]. The aim of the study was to investigate the effects of weight reduction via life style intervention on glycemic control and sleep quality among obese type 2 diabetic patients.

Concerning sleep quality parameter, there was a significant increase in the total sleep duration, sleep efficiency and sleep onset latency in group (A) after 6 months of life style intervention (aerobic exercise and diet regimen), while, awake time after sleep onset and REM latency significantly reduced compared with values obtained prior to life style intervention (Table 2). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study for life style intervention and quality of sleep among type 2 diabetic patients as all previous studies were concerned with the life style intervention and obstructive sleep apnea and the impact of exercise training and quality of sleep.

Reid et al had Seventeen sedentary elderly subjects with insomnia who had 16 weeks of aerobic physical activity. The clearly stated that physical activity improved sleep quality on the global Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) score, sleep latency sleep duration, daytime dysfunction and sleep efficiency [38]. Where, Lira et al. conducted a study on fourteen male sedentary, healthy, elderly volunteers performed moderate training for 60 minutes/day, 3 days/week for 24 weeks at a work rate equivalent to the ventilatory aerobic threshold. They proved that sleep parameters, awake time and REM sleep latency decreased after 6 months exercise training in relation baseline values [39]. In addition, Yang and colleagues completed a systematic review with meta-analysis of six randomized trials and provided data on 305 participants (241 female). Each of the studies examined an exercise training program that consisted of either moderate intensity aerobic exercise or high intensity resistance exercise. The duration of most of the training programs was between 10 and 16 weeks. All of the studies used the self-reported Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index to assess sleep quality. Compared to the control group, the exercise group had significantly reduced sleep latency and medication use [40]. While, Chen and coworkers enrolled twenty-seven participants in 12 weeks of Baduanjin exercise training, they proved that overall sleep quality, subjective sleep quality, sleep latency, sleep duration, sleep efficiency, and daytime dysfunction significantly improved after 12 weeks of intervention [41]. In addition, Santos et al had twenty-two male, sedentary, healthy, elderly volunteers performed moderate training for 60min/day, 3 days/week for 24 week at a work rate equivalent to their ventilatory aerobic threshold, their findings suggest that aerobic exercise training increased aerobic capacity parameters, decreased REM latency and decreased time awake [42]. Moreover, Passos and colleagues concluded that a 4-month intervention of moderate aerobic exercise delivered to twenty- one sedentary participants with chronic primary insomnia had polysomnographic data significantly improvements following exercise training, where total sleep time, sleep efficiency and rapid eye movements significantly increased. In addition, sleep onset latency and wake time after sleep onset significantly decreased following exercise training [43].

Regarding, the mechanism underlying the effect of life style intervention on sleep, although the mechanisms by which life style intervention can improve sleep quality are not well understood. However, extra energy consumption, endorphin secretion, secretion of anti-inflammatory cytokines or modulation of body temperature in a manner that facilitates sleep for recuperation of the body in addition to reduced resting plasma concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokines may be the possible mechanisms for sleep quality parameter improvement because of life style intervention [40,44-47].

Regarding glycemic control, the results of the present study proved that life style intervention (aerobic exercise and diet regimen) significantly improved insulin sensitivity and reduced insulin resistance because of weight reduction. These results agreed with Angelico et al. proved that 5%-10% weight loss as a result of diet regimen modulates insulin resistance in patients with metabolic syndrome [48], also Albu and colleagues mentioned that lifestyle modifications with diet and exercise are essential part of the management of the diabetes obese patient as weight loss leads to improvement in the glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, reductions in lipid levels [49]. While, weight reduction program consisted of diet restriction and exercise, which was conducted on thirty-five obese T2DM patients for twelve weeks (diet restriction and exercise), induced significant reductions in body weight, serum leptin levels, improvements in lipoprotein profile, insulin sensitivity and glucose control [50]. Several mechanisms have been proposed to be responsible for the increases in insulin sensitivity after exercise training. These include increased post-receptor insulin signaling, increased glucose transporter protein and mRNA, increased activity of glycogen syntheses and hexokinase, decreased release and increased clearance of free fatty acids, increased muscle glucose delivery and changes in muscle composition [51]. Moreover, energy restriction resulting in even modest weight loss suppresses endogenous cholesterol synthesis that leads to a decline in circulating lipid concentrations and because of increased insulin sensitivity [52,53]. Through decreasing deposition of total fat and intra-abdominal fat [54].

Conclusion

Life style intervention is an effective modality for modifying glycemic control and sleep quality among obese type 2 diabetic patients.

Acknowledgment

The author is thankful for Prof. Shehab M. Abd El-Kader, professor of physical therapy for his sharing in application of procedures of this research.

References

- Finucane M, Stevens G, Cowan M, Danaei G, Lin JK, et al. (2011) National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 377(9765): 557-567.

- Whiting D, Guariguata L, Weil C, Shaw J (2011) IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of the prevalence of diabetes for 2011 and 2030. Diabetes Res Clin Pract 94(3): 311-321.

- McCrimmon R, Ryan C, Frier B (2012) Diabetes and cognitive dysfunction. Lancet 379(9833): 2291-2299.

- Lau DCW. "Let's take control of diabetes. Now” Why and How? Can J Diabetes 2010; 34:317-319.

- DePablos-Velasco P, Salguero-Chaves E, Mata-Poyo J, DeRivas-Otero B, García-Sánchez R, et al. (2014) Quality of life and satisfaction with treatment in subjectswith type 2 diabetes: Results in Spain of the PANORAMA study. Endocrinol Nutr 61(1): 18-26.

- Lau D (2011) New insights in the prevention and early management of type 2 diabetes. Can J Diabetes 35(3): 239-241.

- Sharma A, Lau D (2013) Obesity and Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus. Can J Diabetes 37(2): 63-64.

- Qian J, Scheer FA (2016) Circadian system and glucose metabolism: implications for physiology and disease. Trends Endocrinol Metab 27(5): 282-293.

- Defronzo R (2009) Banting Lecture. From the triumvirate to the ominous octet: A new paradigm for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes 58(4): 773-795.

- Shan Z, Ma H, Xie M, Yan P, Guo Y, et al. (2015) Sleep duration and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 38(3): 529-537.

- Tang Y, Meng L, Li D, Yang M, Zhu Y, et al. (2014) Interaction of sleep quality and sleep duration on glycemic control in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Chin Med J (Engl) 127(20): 3543-3547.

- Knutson KL, Ryden AM, Mander BA, Van Cauter E (2006) Role of sleep duration and quality in the risk and severity of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med 166(16): 1768-1774.

- Tsai YW, Kann NH, Tung TH, Chao YJ, Lin CJ, et al. (2012) Impact of subjective sleep quality on glycaemic control in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Fam Pract 29(1): 30-35.

- Trento M, Broglio F, Riganti F, Basile M, Borgo E, et al. (2008) Sleep abnormalities in type 2 diabetes may be associated with glycaemic control. Acta Diabetol 45(4): 225-229.

- Akinnusi ME, Saliba R, Porhomayon J, El-Solh AA (2012) Sleep disorders in morbid obesity. Eur J Intern Med 23(3): 219-226.

- Alkatib S, Sankri-Tarbichi AG, Badr MS (2014) The impact of obesity on cardiac dysfunction in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Breath 18(1): 137-142.

- Slater G, Pengo MF, Kosky C, Steier J (2013) Obesity as an independent predictor of subjective excessive daytime sleepiness. Respir Med 107(2): 305-309.

- Schmid SM, Hallschmid M, Schultes B (2015) The metabolic burden of sleep loss. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 3(1): 52-62.

- Heffner JE, Rozenfeld Y, Kai M, Stephens EA, Brown LK (2012) Prevalence of diagnosed sleep apnea among patients with type 2 diabetes in primary care. Chest 141(6): 1414-1421.

- West SD, Nicoll DJ, Stradling JR (2006) Prevalence of obstructive sleep apnoea in men with type 2 diabetes. Thorax 61(11): 945-950.

- Einhorn D, Stewart DA, Erman MK, Gordon N, Philis-Tsimikas A, et al. (2007) Prevalence of sleep apnea in a population of adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Endocr Pract 13(4): 355-362.

- Plantinga L, Rao MN, Schillinger D (2012) Prevalence of self-reported sleep problems among people with diabetes in the United States, 2005-2008. Prev Chronic Dis 9: E76.

- Nedeltcheva AV, Scheer FA (2014) Metabolic effects of sleep disruption, links to obesity and diabetes. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 21(4): 293-298.

- Martins RC, Andersen ML, Tufik S (2008) The reciprocal interaction between sleep and type 2 diabetes mellitus: facts and perspectives. Braz J Med Biol Res 41(3): 180-187.

- American Diabetes Association (2010) Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care 33(Suppl 1): S62-S69.

- Rechtschaffen A, Kales AA (1968) Manual of standardized terminology, techniques, and scoring system for sleep stages of human subjects. Brain Information Service/Brain Research Institute/UCLA, Los Angeles, USA.

- Matthews DR, Hosker JP, Rudenski AS, Naylor BA, Treacher DF, et al. (1985) Homeostasis model assessment: insulin resistance and beta cell function from plasma FBS and insulin concentrations in man. Diabetologia 28(7): 412-419.

- Katz A, Nambi SS, Mather K, Baron DA, Follman DA, et al. (2000) Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index: a simple, accurate method for assessing insulin sensitivity in humans. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 85(7): 2402-2410.

- Thompson WR, Gordon NF, Pescatello LS (2009) ACSM's guidelines for exercise testing and prescription: Hubsta Ltd 2009.

- Sciacqua A, Candigliota M, Ceravolo R, Scozzafava A, Sinopoli F, et al. (2003) Weight loss in combination with physical activity improves endothelial dysfunction in human obesity. Diabetes Care 26(6): 16731678.

- World Health Organization (1990) Diet, nutrition, and the prevention of chronic diseases. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser 797: 1-204.

- Murakami T, Horigome H, Tanaka K, Nakata Y, Ohkawara K, et al. (2007) Impact of weight reduction on production of platelet-derived microparticles and fibrinolytic parameters in obesity. Thromb Res 119(1): 45-53.

- Shan Z, Ma H, Xie M, Yan P, Guo Y, et al. (2015) Sleep duration and risk of type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. Diabetes Care 38(3): 529-537.

- Cappuccio FP, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA (2010) Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care 33(2): 414-420.

- Gupta S, Wang Z (2016) Predictors of sleep disorders among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Metab Syndr 10(4): 213-220.

- Lee SW, Ng KY, Chin WK (2016) The impact of sleep amount and sleep quality on glycemic control in type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev 31: 91-101.

- Mohammad S, Ahmad J (2016) Management of obesity in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus in primary care. Diabetes Metab Syndr 10(3): 171-181.

- Reid KJ, Baron KG, Lu B, Naylor E, Wolfe L, et al. (2010) Aerobic exercise improves self-reported sleep and quality of life in older adults with insomnia. Sleep Med 11(9): 934-940.

- Lira FS, Pimentel GD, Santos RV, Oyama LM, Damaso AR, et al. (2011) Exercise training improves sleep pattern and metabolic profile in elderly people in a time-dependent manner. Lipids Health Dis 10: 1-6.

- Yang PY, Ho KH, Chen HC, Chien MY (2012) Exercise training improves sleep quality in middle-aged and older adults with sleep problems: a systematic review. J Physiother 58(3): 157-163.

- Chen M, Liu H, Huang H, Chiou A (2012) The effect of a simple traditional exercise programme (Baduanjin exercise) on sleep quality of older adults: A randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud 49(3): 265-273.

- Santos RV, Viana VA, Boscolo RA, Marques VG, Santana MG, et al. (2012) Moderate exercise training modulates cytokine profile and sleep in elderly people. Cytokine 60(3): 731-735.

- Passos GS, Poyares D, Santana MG, Teixeira AA, Lira FS, et al. (2014) Exercise Improves Immune Function, Antidepressive Response, and Sleep Quality in Patients with Chronic Primary Insomnia. Biomed Res Int 2014: 498961.

- Horne JA, Moore VJ (1985) Sleep EEG effects of exercise with and without additional body cooling. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 60(1): 33-38.

- Driver HS, Taylor SR (2000) Exercise and sleep. Sleep Med Rev 4(4): 387-402.

- Li F, Fisher KJ, Harmer P, Irbe D, Tearse RG, et al. (2004) Tai chi and self-rated quality of sleep and daytime sleepiness in older adults: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc 52(6): 892-900.

- Kapsimalis F, Basta M, Varouchakis G, Gourgoulianis K, Vgonzas A, et al. (2008) Cytokines and pathological sleep. Sleep Med 9(6): 603-614.

- Angelico F, Loffredo L, Pignatelli P, Augelletti T, Carnevale R, et al. (2012) Weight loss is associated with improved endothelial dysfunction via NOX2-generated oxidative stress downregulation in patients with the metabolic syndrome. Intern Emerg Med 7(3): 219-227.

- Albu J, Raja- Khan N (2003) The management of the obese diabetic patient. Prim Care 30(2): 457-491.

- Ruche R, McDonald R (2001) Use of antioxidants nutrients in the prevention and treatment of type 2 diabetes. J Coll Nutr 20(5 Suppl): S363-S369.

- Ahmadizad S, Haghighi AH, Hamedinia MR (2007) Effects of resistance versus endurance training on serum adiponectin and insulin resistance index. Eur J Endocrinol 157(5): 625-631.

- Di Buono M, Hannah JS, Katzel LL, Jones PJ (1999) Weight loss due to energy restriction suppresses cholesterol biosynthesis in overweight, mildly hypercholesterolemic men. J Nutr 129(8): 1545-1548.

- Lamarche B, Despress J, Pouliot MC, Moorjani S, Lupien P, et al. (1992) Is body fat loss a determinant factor in the improvement of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism following aerobic exercise training in obese women?. Metabolism 41(11): 1249-1256.

- Kriska A, Pereira M, Hanson R, de Courten MP, Zimmet PZ, et al. (2001) Association of physical activity and serum insulin concentration in two populations at high risk for type 2 diabetes but differing by BMI. Diabetes Care 24(7): 1175-1180.