Impact of Acne on Patients' Quality of Life in Bulgaria

Petkova V1*, Husain S1, Dimitrov M2, Lambov N2, Tzvetkova A3 and Todorova A3

1Department of Social Pharmacy, Medical University Sofia, Bulgaria

2Department of Pharmaceutical Technology and biopharmacy, Medical University Sofia, Bulgaria

3Medical University Varna, Bulgaria

Submission: January 04, 2018; Published: April 16, 2018

*Corresponding author: Valentina Petkova, DSc, PhD, Professor, Medical University Sofia, 2-Dunav str., Sofia-1000, Bulgaria; Tel: +35929236593; Email: petkovav1972@yahoo.com

How to cite this article: Petkova V, Husain S, Dimitrov M, Lambov N, Tzvetkova A and Todorova A. Impact of Acne on Patients' Quality of Life in Bulgaria. J Endocrinol Thyroid Res . 2018; 3(3): 555613. DOI: 10.19080/JETR.2018.03.555613

Abstract

Background: Acne vulgaris is not only the most common endocrinology and skin disorder, but it causes considerable QoL worsening. The social, psychological, and emotional impairment of the disease, can be associated with those caused by epilepsy, asthma, diabetes, and other socially important chronic diseases.

Objective: This study aims to determine the impact of acne on quality of life in Bulgaria using the Cardiff acne disability index (CADI).

Methods: A pilot cross-sectional survey was conducted in a sample of individuals aged 11 to 30 (n=30) from Sofia, Bulgaria that were diagnosed with acne. Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI) was applied to collect the data. The CADI scale was translated into Bulgarian and standardized by forward translation, backward translation, and a pretest. The data collected were proceeded through SPSS ver. 22.0.

Results: Mean participant age was 21.7 year. Severe acne was more common among females than males (20% vs. 13.3%). There is no significant prevalence of the disease with the age (p=0.125). BMI is not a factor. The maximum CADI score for the sample was 11 in the male group. The mean score was 6.1±1.12 which implied that the majority of them had moderate impairment and mild psychological impact.

Conclusion: Cardiff Acne Disability Index is a good tool to be assessed the quality of life in patients with acne. The result from the pilot study shows that acne worsens the QoL of the patients affected. The situation of the Bulgarian patients with acne is the same as in the rest of the Eastern Europeans from QoL point of view. Because the venue of this study is pharmacy and not a hospital, it may help patients with low socioeconomic status to consult and ask for appropriate treatment.

Introduction

Acne vulgaris is a common inflammatory pilosebaceous disease with prevalence reaching up to 80% during adolescence, characterized by comedones, papules, pustules, inflamed nodules, etc. [1,2]. Acne is not only the most common endocrinology and skin disorder, but it is also the pathology with the highest cumulative incidence among the general population [3].

It is estimated to affect 9.4% of the global population, making it the eighth widespread disease worldwide [4,5]. According to some studies it affects over 80% of teenagers (aged 13-18 years) at some point [6]. The data about the disease's prevalence vary depending on the study populations and the method of assessment applied. Prevalence of acne in a community sample of 14- to 16-year-olds in the UK has been recorded as 50% [7]. Overall incidence is similar in both men and women, and peaks at 17 years of age [8]. The data about New Zealand, shows that acne was present in 91% of males and 79% of females, and in a similar population in Portugal the prevalence was 82% [9,10]. It has been estimated that up to 30% of teenagers have acne of sufficient severity to require medical treatment [8]. The number of adults with acne, including people over 25 years, is increasing; the reasons for this increase are uncertain [11]. Some authors confirm that the cumulative incidence of acne is 91% in males and 79% in females during adolescence, that drops to 3% in males and 12% in females during adulthood [12]. Different studies reported an acne incidence of 55% in males and 45% in females aged 14 to 16 years [7]. whilst other authors stated a 29% incidence in boys and 16% in girls, per year, in a population aged between 16 and 20 years old [13]. White et al. reported an acne incidence of 85% in male adolescents and 80% in female adolescents, which dropped to 8% in the age group 25 to 34 and 3% in those aged 35 to 44 years [14].

The prevalence of acne varies by gender and age groups, appearing earlier in females (11 years old) than in males (1213 years old), and the reason for that can be the earlier onset of puberty [15]. Peak incidence of acne is between years 17-18 of age for females and 19-21 for males. There is a greater severity of acne in males than in females in the late teens, which can be correlated with androgens being a potent stimulant of sebum secretion [15].

There are no racial differences in term of incidence, but in the development of lesions and long-term sequelae, with marked differences between Caucasian and black people. There are evidences that the latter seem to have a higher risk of developing severe inflammatory and cicatricial sequelae [16]. The exact cause of acne is unknown. There are four factors proven to contribute to the development of acne: increased sebum secretion rate, abnormal follicular differentiation causing obstruction of the pilosebaceous duct, bacteriology of the pilosebaceous duct, and inflammation [17]. The anaerobic bacterium Propionibacterium acnes plays an important role in the pathogenesis of acne. Androgen secretion is the major trigger for adolescent acne [18].

Other contributing factors, such as genetic factors, emotional stress, diet and personal hygiene, those associated with the most severe forms of acne have yet to be studied and confirmed [19,20]. It is classified as mild, moderate, or severe [2]. Even if acne is not associated with severe morbidity, mortality or physical disability, it causes considerable psychological and social consequences [21]. Acne can lead to scarring and considerable psychological distress [23]. The social, psychological, and emotional impairment of the disease, can be associated with those caused by epilepsy, asthma, and diabetes [23]. Patients could suffer from depression, anxiety, social withdrawal, and anger, without considering that scarring can lead to lifelong problems with self-esteem [23]. Some studies on the impact of acne have proven dissatisfaction with appearance, embarrassment, self-consciousness, and lack of self-confidence in acne patients [24-26]. There are evidences that acne could be associated with anxiety, depression [27], feel of anger [28], and lower body satisfaction [29]. There is lack of data on the quality of life impact of acne in Bulgaria. Bulgaria is populated by 7,101,859 people comprising 3 ethnic groups [30]. This study was undertaken to determine the impact of acne on quality of life using the Cardiff acne disability index (CADI).

Materials and Methods

A pilot cross-sectional survey was conducted in a sample of individuals aged 11 to 30 (n=30) from Sofia, Bulgaria that were diagnosed with acne. Patients were recruited from pharmacies in Sofia, based on referrals from pharmacists. The Ethics Committee of the Medical University of Sofia approved the study protocol. All participants provided written informed consent before entering the study, and all questionnaires were made anonymous before evaluation.

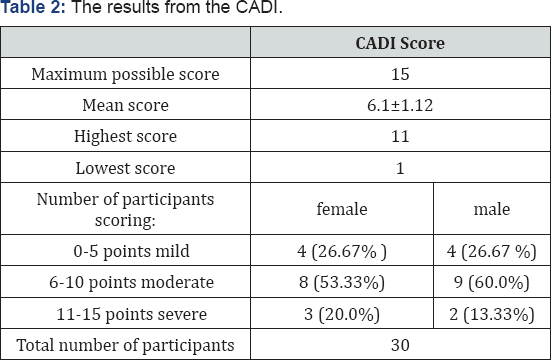

Data were collected via the Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI). The Cardiff Acne Disability Index (CADI). Motley & Finlay [31] is a short 5 item questionnaire derived from the longer Acne Disability Index. The Cardiff Acne Disability Index is designed for use in teenagers and young adults with acne. It is self-explanatory and can be simply handed to the patient who is asked to complete it without the need for detailed explanation. Each question contains 4 possible answers with a score of 0~4. The CADI score is calculated by summing the score of each question resulting in a possible maximum score of 15 and a minimum score of 0. A score of 0~5 translates to mild quality of life impairment, 6~10 indicates moderate impairment, and 11~15 demonstrates severe impairment. The CADI scale was translated into Bulgarian and standardized by forward translation, backward translation, and a pretest [32]. The data collected were proceeded through SPSS ver. 22.0.

Results

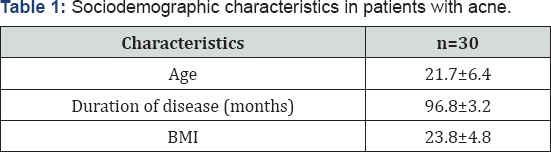

A total of 40 patients were included in the pilot study - 20 males and 20 females. The number of completed questionnaires returned was 30, a response rate of 75% while 10 (25%) questionnaires were incomplete. Mean participant age was 21.7 year. Severe acne was more common among females than males (20% vs. 13.3%). There is no significant prevalence of the disease with the age (p=0.125). BMI is not a factor. The mean BMI is 23.8±4.8 (Table 1).

The maximum CADI score of 15 was not achieved. The maximum CADI score for the sample was 11 in the male group. The mean score was 6.1±1.12 which implied that the majority of them had moderate impairment and mild psychological impact. There was no significant association between CADI score and gender (p=0.123) (Table 2). It is an important finding, as there is a perception among some health professionals that facial acne has less impact on males.

Discussion

Acne vulgaris is a chronic inflammatory disease with a complex pathogenesis that affects predominantly adolescents. It affects quality of life. Our study shows that males were more affected than females in the age group 18-21. The QOL is more affected negatively in the age group 21-25 years, and this result agrees with some conclusions in the literature [33]. In the current study, the males' QOL was significantly more affected than that of females, from severity point of view as agrees with other studies [34], and this may be because the females take more care about their hygiene and appearance in the community. The results from our study shows nearly the same results as the similar study in Greece [35]. Of course the results cannot be directly compared as different questionnaires were applied.

But as quality of life is completely a subjective issue, the severity of lesions cannot exactly determine the quality of life. There are some other factors that must be considered, such as social, personal, emotional, and school problems [36]. In the present study, there was no significant relationship between quality of life and duration of diseases. This result emphasizes the point that the effect of acne on quality of life is independent of disease duration and is mostly dependent on personal characteristics and patients' ability in accepting their disease and copying with its problems. These results confirm the results from Kokandi study [37]. The study results confirm the seriousness of the disease and shows that its influence on patients' quality of life is comparable to some social and rare diseases such as liver, kidney diseases and diabetes [38-40].

Conclusion

Cardiff Acne Disability Index helps to assess the quality of life in patients with acne. The CADI contains five questions that focus on feelings, social life, avoidance of public activities and assessment of acne severity (maximum possible score 15). The result from the pilot study shows that acne worsens the QoL of the patients affected. The situation of the Bulgarian patients with acne is the same as in the rest of the Eastern Europeans from QoL point of view.

Because the venue of this study is pharmacy and not a hospital, it may help patients with low socioeconomic status to consult and ask for appropriate treatment. Despite this limitation, this is the first study to be achieved regarding QOL of patients with acne and it can be used as a base for future studies about QOL of patients with skin diseases.

References

- Rzany B, Kahl C (2006) Epidemiologie der acne vulgaris. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges 4(1): 8-9.

- Healy E, Simpson N (1994) Acne vulgaris. BMJ 308(6932): 831-833.

- Semyonov L (2010) Acne as a public health problem. Ital J Public Health 7(2): 112-114.

- Tan JK, Bhate K (2015) A global perspective on the epidemiology of acne. Br J Dermatol 172(Suppl 1): 3-12.

- Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C (2012) Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990-2010: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380(9859): 2163-2196.

- Chu TC (1997) Acne and other facial eruptions. Medicine 25: 30-33.

- Smithard A, Glazebrook C, Williams HC (2001) Acne prevalence, knowledge about acne and psychological morbidity in mid-adolescence: a community-based study. Br J Dermatol 145(2): 274-279.

- Garner S (2003) Acne vulgaris. In: Williams H (Edt.), Evidence-based dermatology. BMJ, London, UK, England, pp. 87-114.

- Pearl A, Arroll B, Lello J, Birchall NM (1998) The impact of acne: a study of adolescents' attitudes, perception and knowledge. N Z Med J 111(1070): 269-271.

- Amado JM, Matos ME, Abreu AM, Loureiro L, Oliveira J, et al. (2006) The prevalence of acne in the north of Portugal. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol 20(10): 1287-1295.

- Cunliffe WJ (1998) Management of adult acne and acne variants. J Cutan Med Surg 1998;2(suppl 3):7-13.

- Tan JK, Vasey K, Fung KY (2001) Beliefs and perceptions of patients with acne. J Am Acad Dermatol 44(3): 439-445.

- Aktan S, Ozmen E, Sanli B (2001) Anxiety, depression, and nature of acne vulgaris in adolescents. Int J Dermatol 39(5): 354-357.

- White MG (1998) Recent findings in the epidemiologic evidence, classification, and subtypes of acne vulgaris. J Am Acad Dermatol 39: 34-37.

- Stathakis V, Kilkenny M, Marks R (1997) Descriptive epidemiology of acne vulgaris in the community. Australas J Dermatol 38(3): 115-123.

- Davis EC, Callender VD (2010) A Review of Acne in Ethnic Skin: Pathogenesis, Clinical Manifestations, and Management Strategies. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol 3(4): 24-38.

- Brown SK, Shalita AR (1998) Acne vulgaris. Lancet 351(9119): 18711876.

- Webster GF (1999) Acne vulgaris: state of the science. Arch Dermatol 135(9): 1101-1102.

- Sahlander K, Larsson K, Palmberg L (2010) Altered innate immune response in farmers and smokers. Innate Immun 16(1): 27-38.

- Schäfer T, Nienhaus A, Vieluf D, Berger J, Ring J (2001) Epidemiology of acne in the general population: the risk of smoking. Br J Dermatol 145(1): 100-104.

- Purdy S, Langston J, Tait L (2003) Presentation and management of acne in primary care: a retrospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract 53(492): 525-529.

- Mallon E, Newton JN, Klassen A, Stewart-Brown SL, Ryan TJ, et al. (1999) The quality of life in acne: a comparison with general medical conditions using generic questionnaires. Br J Dermatol 140(4): 672676.

- James WD (2005) Clinical practice. Acne. N Engl J Med 352(14): 14631472.

- Tan JKL (2004) Psychosocial impact of acne vulgaris: evaluating the evidence. Skin Therapy Lett 9(7): 1-9.

- Magin P, Adams J, Heading G, Pond D, Smith W (2006) Psychological sequelae of acne vulgaris: results of a qualitative Dermatology Research and Practice study. Can Fam Physician 52: 978-979.

- Purvis D, Robinson E, Merry S, Watson P (2006) Acne, anxiety, depression and suicide in teenagers: a cross-sectional survey of New Zealand secondary school students. J Paediatr Child Health 42(12): 793-796.

- Kellett SC, Gawkrodger DJ (1999) The psychological and emotional impact of acne and the effect of treatment with isotretinoin. Br J Dermatol 140(2): 273-228.

- Rapp DA, Brenes GA, Feldman SR, et al. (2004) Anger and acne: implications for quality of life, patient satisfaction and clinical care. Br J Dermatol 151(1): 183-189.

- Dalgard F, Gieler U, Holm J, Bjertness E, Hauser S (2008) Self-esteem and body satisfaction among late adolescents with acne: results from a population survey. J Am Acad Dermatol 59(5): 746-751.

- NSI Census data (2011) Population grid, 1 sq.km, Census 2011.

- Motley RJ, Finlay AY (1992) Practical use of a disability index in the routine management of acne. Clin Exp Dermatol 17(1): 1-3.

- WHO Process of translation and adaptation of instruments.

- Cunliffe WJ (1998) Management of adult acne and acne variants. J Cutan Med Surg 2(suppl 3): 7-13.

- Tasoula E, Gregoriou S, Chalikias J, et al. (2012) The impact of acne vulgaris on quality of life and psychic health in young adolescents in Greece. Results of a population survey. An Bras Dermatol 87(6): 862869.

- Ilgen E, Derya A (2005) There is no correlation between acne severity and AQOLS/DLQI scores. J Dermatol 32(9): 705-710.

- Kokandi A (2010) Evaluation of Acne Quality of Life and Clinical Severity in Acne Female Adults. Dermatol Res Pract 2010: 410809.

- Petrov K, Kobakov G, Manova M, Mitov K, Savova A, et al. (2012) Influence of the choice of volatile anesthetics on liver enzymes after the surgical liver resections. Acta Medica Bulgarica (XXX1X)1: 3-8.

- Georgieva Svetla, Maria Kamusheva, Dragana Lakic, Konstantin Mitov, Alexandra Savova, et al. (2012) The health related quality of life for kidney transplant patients in Bulgaria - a pilot study. Biotechnology & Biotechnol Eq 26(3): 3062-3065.

- Yordanova S, Petkova V (2013)Pharmaceutical care in some European countries, Australia, Canada and USA. World Journal of pharmacy and pharmaceutical sciences 2(5): 2290-2308.

- Petkova V, Nikolova 1, Dimitrov M, Andreevska K, Karamancheva L (2011) Prevalence of gestational diabetes in some eastern European countries. Archives of the Balkan Medical Union 46(4): 22-25.