Impact of Pediatric Pneumococcal Vaccination on Pneumonia and Pneumococcal Diseases Hospitalizations in children and adults in a private hospital. Uruguay

Mercedes Sánchez-Varela1, Adriana Varela2, Marcelo Eduardo Chiarella3, Jorge Facal3, Gabriela Algorta2 and María CatalinaPírez1*

1Paediatrics Departments, British Hospital, Montevideo, Uruguay

2Microbiology Laboratory British Hospital, Montevideo, Uruguay

3Medicine Department of Medicine British Hospital, Montevideo, Uruguay

Submission: January 13, 2026; Published: January 26, 2026

*Corresponding author: María Catalina Píez, Paediatrics Departments, British Hospital, Montevideo, Uruguay.

How to cite this article: Mercedes Sánchez-V, Adriana V, Marcelo Eduardo C, Jorge F, Gabriela A, et al. Impact of Pediatric Pneumococcal Vaccination on Pneumonia and Pneumococcal Diseases Hospitalizations in children and adults in a private hospital. Uruguay. Int J Pul & Res Sci. 2025; 8(3): 555737.DOI: 10.19080/IJOPRS.2026.08.555737

Abstract

Introduction: Uruguay introduced PCV7 (2+1 schedule) in 2008, replaced by PCV13 in 2010. Since 2015 adults may receive pneumococcal vaccines. This study evaluates the impact of universal vaccination (UV) on pneumococcal pneumonia and other invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) hospitalizations in a private hospital.

Methods: This retrospective study analysed median hospitalization rates per 10,000 discharges across three periods: pre-PCV (2006-2007),

early post-PCV (2009-2015), and late post-PCV (2016-2022). Cases were defined by S. pneumoniae isolation from sterile sites in children (<15

years) and adults (≥15 years).

Results: Between 2006 and 2022, 121 IPD cases were hospitalized (33 children, 88 adults). In children, hospitalization rates decreased by 83%

in 2009-2015 and 92% in 2016-2022 (p<0.0000). Adult rates declined by 62.4% and 66%, respectively (p=0.0001). Pneumonia was the primary

diagnosis (children 66.6%, adults 77%). Adult mortality significantly decreased (p=0.03). The fatality rate in adults was 9%. One non-vaccinated

child died in 2008. PCV13 serotypes (ST) declined significantly: from 97% to 50% in children and from 77% to 34% in adults (p<0.0000).

Conversely, non-PCV13-ST In period 2016-2022, 5 hospitalizations occurred for serotypes 14, 3, 7B/C, 22F, and 15B. In adults increased from

16% to 56% (p<0.0000), with ST 12F, 8, 22F, and 9N being the most prevalent in the final period.

Conclusion: UV implementation led to a significant reduction in IPD hospitalizations and mortality across all ages, suggesting strong herd

immunity. However, the rise of non-PCV13 serotypes emphasizes the need for continuous epidemiological surveillance to guide future vaccination

strategies.

Keywords:Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine; Pneumococcal vaccination; Invasive pneumococcal disease; Streptococcus pneumoniae; Herd effect

Abbreviations:PCV: Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine; UV= Universal Vaccination; Pre-PCV= Previous PCV Vaccination; Post-PCV= after PCV Vaccination; ST = Serotype; PP= Pneumococcal Pneumonia; IPD = Invasive Pneumococcal Disease; PM= Pneumococcal Meningitis

Introduction

Invasive Pneumococcal Diseases (IPD) represents a significant cause of morbidity and mortality among children and adults [1,2]. Community Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) is the most frequent severe disease and cause of death [1,2]. Pediatric universal pneumococcal vaccination with conjugate vaccines (PCVs) thought a direct effect reduced significantly pneumococcal disease in children. PCVs protect unvaccinated population groups through indirect effect, mediated by a reduction of pneumococcal vaccine serotypes (VST) nasopharyngeal carriage in vaccinated children and thus transmission to non-vaccinated persons [3,4]. Surveillance of IPD caused by non -vaccine serotype (NVST) is an important issue for detect changes in IPD due to these serotypes [2-4].

In Uruguay, a South American country, a routine and free infant vaccination with PCV seven valent (PCV7) was implemented on March 2008 in a 2+1 immunization schedule at 2, 4 and 12 months of age. Catch up was offered to children born in 2007 (2 doses) [5,6]. In April 2010, PCV thirteen valent (PCV13) replaced PCV7 (2+1 schedule) [7]. Catch up was offered to children born from 2005 to 2009, (1 dose). PCV7/13 coverage were > 93% for the 3 doses (cohort 2008 and 2009), 98% for dose 1 and 96 % for dose 3 (cohort 2010) [8-10]. Coverage during 2020 for doses 1 and 2 was 94% and 38 % for dose at 12 months. PCV13 coverage for 2021 were: 94% (dose 1), 92.5% (dose 2) and 93,3% for the booster at 12 months of age. Coverage in 2022 were: 99,61 %, 99,26% and 93,74 % for primary doses and booster respectively [8-10]. Since 2004, pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine 23 valent (PPV23) is recommended for all adults > 65 years. Coverage is estimated around 3%. After 2015, adults at high risk for invasive pneumococcal disease (IPD) may receive PPSV23 or combined schedule PCV13+PPSV23 [11].

Incidence a rate of IPD have changed in adults as a result of the indirect effect of universal pneumococcal vaccination in children [2]. British Hospital is a tertiary general private hospital. Clinical and microbiological surveillance of IPD is performed since 2005 in the population assisted in this health care institution. There are international and local data about the direct and indirect effect of children universal vaccination with PCV 13 [6,12,13]. We designed this study to evaluate the potential impact of universal vaccination with PCVs in hospitalizations and mortality for pneumonia and others IPD due to serotypes included in PCV13, in children and adults hospitalized in BH after 14 years of pediatric pneumococcal universal vaccination in Uruguay. It´s important to demonstrate to reduction on IPD for VST and on mortality, as occurred in other countries to reinforce the relevance of pneumococcal vaccination [1,6,12,13]. We consider also important to analyze potential changes in the serotypes involve in IPD in children and adults. The aim of this study was to assess the impact of pneumococcal universal childhood vaccination strategy on hospitalization for IPD in children and adults in a private general hospital.

Methods

This is a descriptive and retrospective study to analyse the epidemiology of patients hospitalized for IPD in a private general hospital before and after the implementation of the universal vaccination with PCV7 and PCV13. The study was conducted at the British Hospital (BH) of Montevideo, which provides private health insurance covering primary, secondary, tertiary and quaternary care. The hospital has a 190 beds dotation, including 33 of them for intensive care.

Population and case definitions

The study population was divided in two groups: children (0 to 14 years and 11 months of age) and adults (> 15 years of age). The children’s group was further subdivided into those under 2 years of age and those over 2 years of age. The case definition of invasive pneumococcal disease was: patients hospitalized for infectious diseases in which a strain of S. pneumoniae was isolated from blood or a sterile fluid (pleural, peritoneal, articular, cerebrospinal) or tissues. For pediatric and adults’ patient’s standard of care practice includes obtaining a chest radiograph and blood cultures for those with suspected pneumonia. Pleural fluid was obtained upon admission, if applicable. Blood, cerebrospinal fluid, articular fluid or tissue cultures were obtained for patients admitted with suspected meningitis, bacteremia, sepsis, osteomyelitis, arthritis, cellulitis, myositis or other infectious disease if applicable. Standard laboratory practice at Microbiology Laboratory of BH includes microscopic examination, culture and susceptibility testing.

Pneumococcal pneumonia was defined as any case with clinical signs of pneumonia and chest radiograph compatible with alveolar or lobar consolidation with or without pleural effusion. Empyema was defined as pneumonia case in which pleural fluid had at least one of the following: LDH >1000U/L, pH <7.20, glucose <40mg/dL, increased cellularity with predominance of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, and bacteria on direct microscopic examination. Pneumococcal meningitis was defined as any case of suspected bacterial meningitis in which the cerebrospinal fluid was compatible with bacterial meningitis (at least one of the following applies: leukocytes >10/mm3, proteins >40mg/dL, or glucose <40mg/dL), and where S. pneumoniae was isolated in CSF and/or blood.

For other infectious disease as occult bacteremia, sepsis, osteomyelitis and arthritis standard guides for clinical diagnosis were used. The study included only patients in which S. pneumoniae was isolated from blood, sterile fluid or tissue. Only cases that had a community onset of the infectious disease were included.

Microbiological procedures

Standard laboratory practice at Microbiology Laboratory of BH includes microscopic examination, culture and susceptibility testing. The strains of S. pneumoniae isolated from patients with IPD were referred to the National Reference Laboratory, Ministry of Health for “quellung” serotyping.

Source of data

Data were obtained from hospital databases, clinical, laboratory and children vaccination records. Data about number of hospitalizations per year were obtained from the medical registration department.

Statistical Considerations

Three following observation periods were defined, the first one before PCVs children universal vaccination (2006 to 2007). The year of implementation (2008), was descript separately because it was the first year of universal vaccination, with an incremental vaccine coverage across the months. The two periods after implementation were: an early post-implementation period (2009 to 2015) and late post-implementation (2016 to 2022). The first period after implementation includes the change from PCV7 to PCV13 and the last one includes 3 years (2020 to 2022) of COVID-19 pandemic. Number of cases of IPD and median rates per 10,000 discharges for IPD (95% confidence interval), and deaths were described for each period and for the year of implementation. The rates per 10.000 discharges (CI95%) of early and late period after children pneumococcal UV implementation were compared with the period before vaccine implementation (2006-2007).

Variables for each study period: group of age, rate of IPD discharges, clinical diagnosis of IPD, vaccination status of the children with IPD due to PCV serotypes and outcomes (discharge or death). Vaccine failure was defined as a child, fully vaccinated according to age hospitalized for a vaccine serotype IPD, at least 2 weeks after receiving the last dose. For each study period the serotypes of the S. pneumoniae strains isolated were described and classified in three groups: PCV7 serotypes, 6 additional PCV13 serotypes and non-PCV-ST. The percentage of PCV13 serotypes for early and late period post-implementation were compared with pre-implementation period. The degree of univariate association was examined using mid-P exact test and Student’s t test when applicable. All reported probability values were 2 tailed, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Ethical Considerations

The study was approved by authorities and Ethic Committee of British Hospital.

Results

Cases, population and discharge rates for IPD for children and adults

In the period between 2006 to 2022, 88 IPD adult cases were hospitalized, median age was 59,3 years (range 15-90). In the group of children patients there were 33 IPD hospitalizations, the median age in the sub-group under two years of age was 12 months (range 7-20) and in the sub-group > 2 years of age the median age was 6 years (range 2-13).

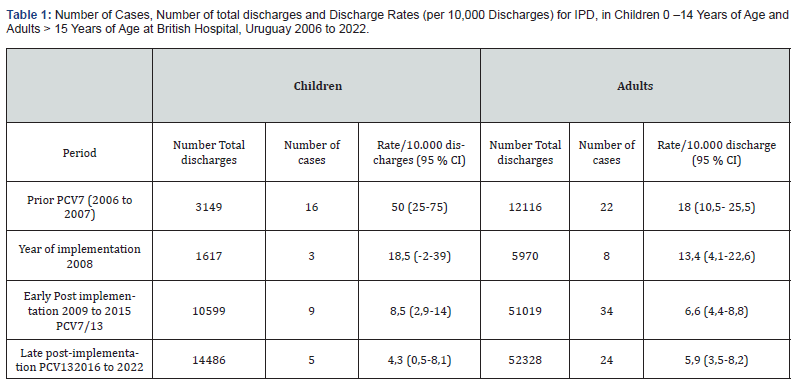

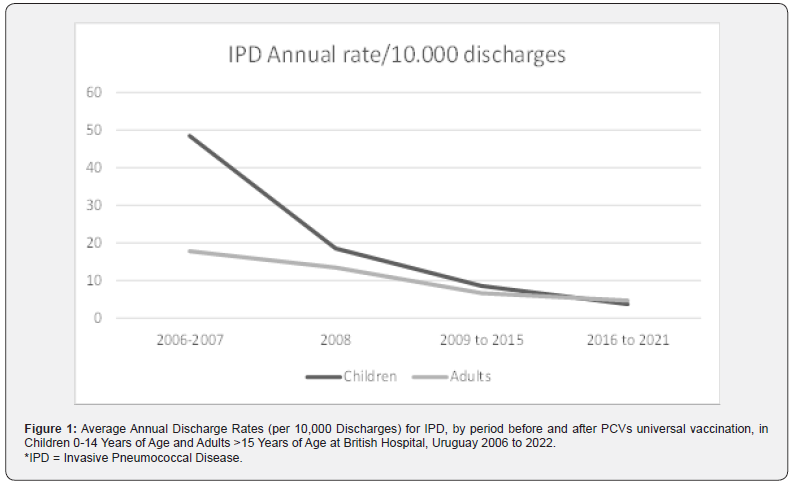

(Table 1) shows the number of cases, total number of discharges and rates/10.000 discharges for IPD by period for children during 2006 to 2022 by period. IPD rate decreased from 50 (25-75) in the pre implementation period (2006 to 2007) to 8,5 (2,9-14) in the early post implementation period, and decreased again to 4,3 (0,5-8,1) in the late post implementation period (p<0.0000001). Representing a significant reduction of 83 and 92 %, respectively. There weren’t pneumococcal isolations in children during 3 years (2019, 2020 and 2021) of the late implementation period. In 2022, one child was hospitalized for IPD. Analysis of discharge rates by period in adult shows a reduction from 17,8 (10,4-25,3) before children universal pneumococcal vaccination (2005 to 2007) to 6,6 (4,4-8,8) in the early post implementation period, and decreased to 5,9 (3,5-8,2) in the late post implementation period (p 0,0001), representing a significant reduction of 62,3 and 66,3% respectively. (Figure 1) shows average annual discharge rate for children and adults in the period before PCV universal vaccination implementation, in the year of implementation and in the two periods after UV vaccine implementation.

IPD = Invasive Pneumococcal Disease.

Cases and Clinical Diagnosis

Children group

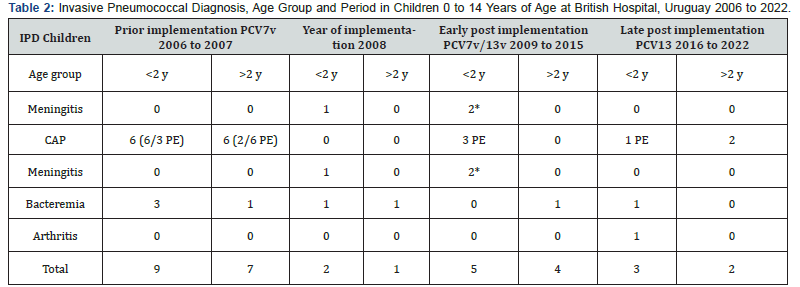

(Table 2) shows the number of cases in children by age group (< 2 years old and 2 to 14 years and 11 months of age) and IPD clinical diagnosis. Pneumococcal pneumonia (PP) was the most frequent disease 22/33 cases (66,6%), followed by bacteremia 8/33. Empyema occurred in 10 of 22 children with PN, one of them with common variable immunodeficiency. In relation to pneumococcal meningitis (PM) 3 hospitalizations occurred, all under 2 years of age. One child in the group < 2 years of age was hospitalized twice due to PM; spinal fluid fistula was diagnosed and repaired. In the same group one child was hospitalized with arthritis.

In 2008, a non-vaccinated child in the group < 2 years of age died; he had an IPD due to S. pneumoniae serotype 14. There weren´t deaths in the other three periods.

IPD= Invasive Pneumococcal Disease, PCV= pneumococcal conjugated vaccine, CAP= Community Acquired Pneumonia PE= pneumococcal empyema CVID= common variable immunodeficiency, y= year.

Adults group

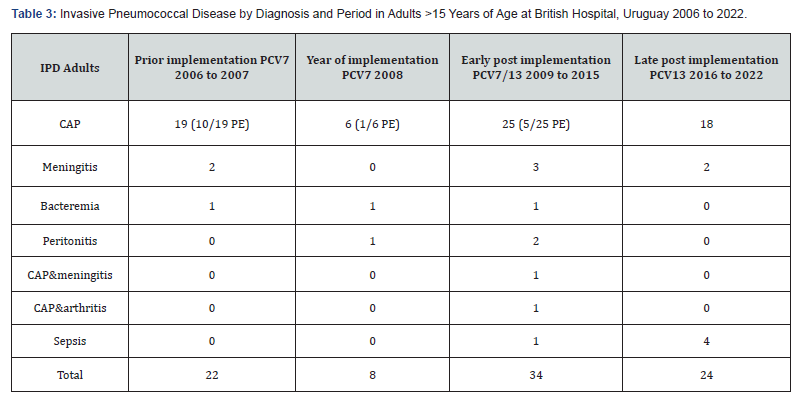

(Table 3) shows the number of cases in adults. In this group, the median age was 59,3 years (range 15 to 90 years), most of them had at least one underlying disease. Pneumococcal pneumonia was the most frequent disease 68/88 cases (77,2%), followed by meningitis (7/88), sepsis (5/88), bacteremia (3/88) and peritonitis (3/88). Two patients were hospitalized due to pneumococcal multifocal disease, pneumonia, arthritis or meningitis. Two patients were hospitalized twice for IPD. Both cases had immunodeficiency The first one was hospitalized for IPD, pneumococcal strains serotypes 12F and 6A were isolated, successively. The second case, was hospitalized for IPD due to serotypes 5 and 7F, respectively.

IPD= Invasive Pneumococcal Disease, CAP= Community Acquired Pneumonia PE= pneumococcal empyema.

The case fatality rate for the whole period was 9 % (CI 95 % 3-15), eight of 88 patients died. The average age of patients who died was 73,5 years (range 62-87) years old. They were hospitalized due to PP, PP with empyema, meningitis and sepsis, one case with SARS-CoV2 coinfection. Three patients belonged to the group of the 22 patients hospitalized in 2006 and 2007. During the 7 years of the early post implementation, period 2009 to 2015, two of the 34 patients died. During the 7 years of the late post- implementation period, from 2016 to 2022, three of the 24 patients died for IPD due to serotypes 14,3 and 8. A significant reduction in mortality was observed (p=0.03)

Pneumococcal serotypes

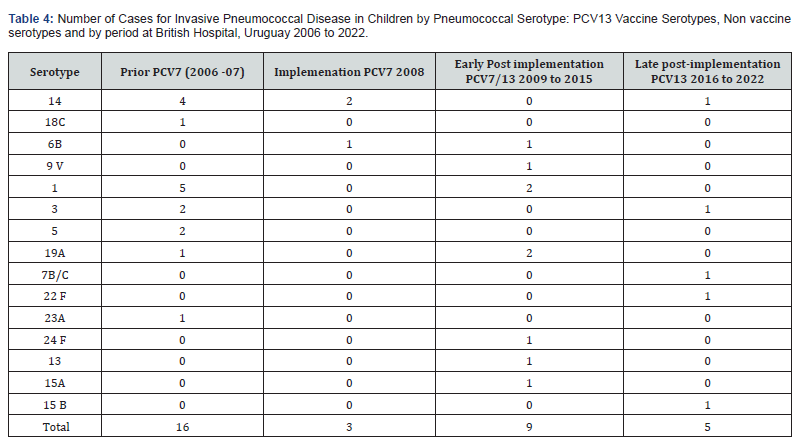

(Table 4) shows the 16 different serotypes isolated from children with IPD, and the number of PCV13 VST and non PCV13 VST by period. After PCV implementation the number of PCV13 VST strains were 15 of 16 (94%), the most frequent were 1, 14, 3 and 5. The non VST isolated was a 23 A serotype. In the year of implementation, the 3 strains were PCV7 VST, two serotype 14 and one 6B. In the early post-implementations period, 6 of the 9 strains were PCV13 VST (one 6B, one 9V, two 1 and one 19A), the other 3 strains were NVST 24 F, 13 and 15 A. For the late postimplementation period, two PCV13 VST were isolated: serotypes 14 and 3, the other three were 7B/C, 22 F, 15 B. A significant reduction of PCV13 VST was observed comparing prior PCV and late implementation periods (p=0.00000000).

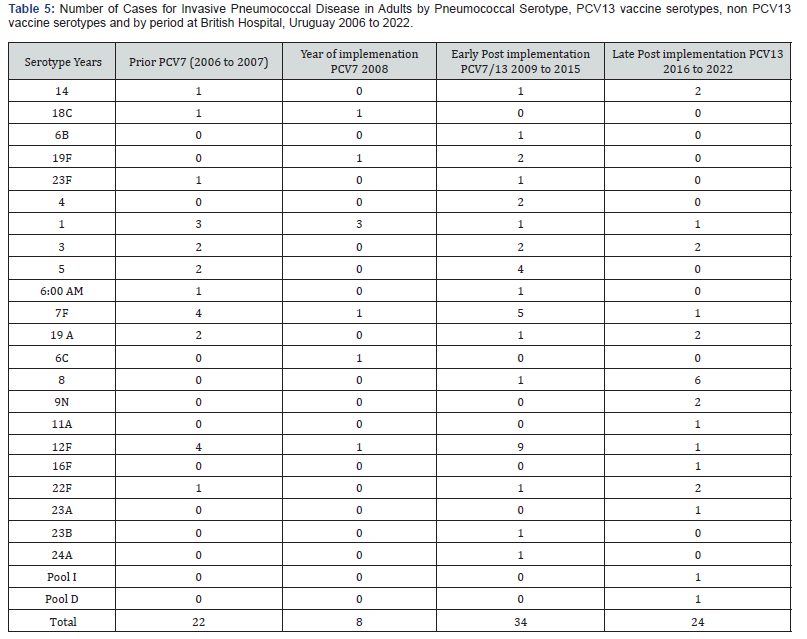

(Table 5) shows the 24 different serotypes isolated from adults. Prior PCV implementation 17/22 (77%) of the strains were PCV13 serotypes; the most frequent were: 1, 5, 3 and 19A. The non-PCV13 ST were 12F (4 strains) and one 22F. The year of implementation, 6/8 strains isolated were PCV13 VST (2 PCV7 and 4 PCV13 serotypes), the two non-PCV13 ST were 6 C and 12F. In the early post-implementations period, 21/34 (61,4%) serotypes were PCV13 serotypes (14, 6B, 19F, 23F, 4, 1, 3, 5, 6A, 7F and 19A), the other 13 strains were non-PCV13 ST, 9 serotype 12 F, one 8, one 22F, one 23 B and one 24 A. For the late postimplementation period, 2/ 24 strains were PCV13 VST (34%), the other 16 strains were NVST, two strains 22 F, six 8, two 9N and 1 strain for each one of following serotypes: 11A, 12F, 16F, 23A, Pool I and Pool D. In adults, a significant reduction of PCV13 VST was also observed comparing prior PCV and late implementation period (p=0.0000002).

An increase of non-PCV-ST was observed, 35 of the 62 (56%) strains isolated between 2009 to 2022 (47 %) comparing with 2006-2007 period in which 6 of the 38 (16%) strains isolated were non-PCV-ST (p<0.0000). Serotypes 12 F, 8, 22F and 9N became the most frequent ST isolated after PCV13 infant vaccination (Tables 3 and 4). In the adult group of patients in the late post implementation period, 16/24 (66 %) of the isolates were NVST. Serotypes 8, 22F and 9N became the most frequent isolated in this period. Serotypes by period and number of isolates were shown in (Table 5).

Children vaccine status

3/31 children fully immunized were hospitalized for PCV13 vaccine serotype IPD. A child was hospitalized twice during his two first of life. The first hospitalization for a 6B IPD in the first years of life, and the second one for IPD due to 19A ST, with 2 doses PCV7 in the first episode and 1 PCV13 dose in the second one; central nervous system malformation was diagnosed and repaired. Two children fully immunized aged ≤5 years, were hospitalized due to VST 3 and 14. No immunodeficiency was diagnosed.

Discussion

Childhood vaccination with PCV vaccines was recommended by WHO for the prevention of IPD and pneumonia, and different programs were implemented since 2000 [1]. Direct and indirect effects of universal children vaccination have been documented in different countries around the world with the same vaccines used in Uruguay [14]. The indirect effect is attributed to the reduction of nasopharyngeal carriage in vaccinated children associated to a high children national coverage [2]. Vaccine benefits in reducing IPD and pneumonia in vaccinated and non-vaccinated groups were observed almost 14 years after PCV7 implementation in Uruguay [6,12,13,15-18].

For the population assisted in BH, the average annual rates for IPD hospitalizations declined significantly after the introduction of universal vaccination with PCVs, and the reduction was statistically significant for children and adults. Pneumococcal pneumonia was the most frequent disease in both groups. This finding was also described in other studies in Uruguay that demonstrated a significant decrease in non-invasive community acquired pneumonia [2,6,16-19] The impact in reducing IPD in children under or up two years of age and adults as a result of universal vaccination with schedule 3+1 or 2 +1 with PCV7 and PCV13 was observed in other countries [2,14,19,20].

During COVID-19 pandemic a decrease in the incidence of IPD, bacteremic and non bacteremic community acquired pneumonia was observed attributed to a reduction in social, virtual educational activities of the population and lesser circulation of seasonal respiratory viruses, especially RSV and influenza virus [21,22]. In Uruguay, lock down was not mandatory and educational activities were exclusively virtual during two periods of around 3 months in 2020 and 2021, but the effect of COVID-19 pandemic in the reduction of circulation of seasonal respiratory virus circulation was the same than in other countries in the region of the Americas [23]. In this study, a significant reduction in hospitalizations because of IPD was observed in the early and late post implementation period. A similar reduction in IPD during 2020 and 2021 was observed also in other countries [21].

After universal childhood PCV vaccine implementation, we observed a significant reduction in IPD due to PCV13 VST in children and adults. The findings of our observational study may be a contribution to demonstrate the importance of maintaining a high infant vaccination coverage for PCV7/13 to reduce IPD. In our population, we didn’t find the increase in IPD during 2022 described in other countries. Nevertheless, the national surveillance system in Uruguay reported a pneumococcal meningitis increase during 2022 [21,24]. During the early and late post implementation periods of PCVs, the reduction in hospitalization due to IPD was sustained for BH population. The reduction during 2021 and 2022 can be explained due to the high PCV vaccine coverage in a country considered with a mature PCV vaccine program [25]. In Uruguay, as in other countries, IPD reduction during COVID-19 pandemic were influenced by a significant reduction in circulation of influenza, VRS and other respiratory virus, specially in 2020 and 2021 [21,22,24]. In our country an important factor that allowed maintaining national PCV coverage during COVID-19 pandemic was the strategy of vaccination; SARS CoV-2 vaccination for the general population was applied in different vaccination centers where PNI vaccines were also administered, facilitating access to them [25].

In this study, a reduction in IPD caused by PCV13 serotypes due to direct effect was observed in children under 2 years of age and indirect effect was observed in children up to 2 years of age and adults. In children, the most frequent VST isolated during the 2 years of pre-vaccination period were 1, 14, 3 and 5 followed by 18 C and 19A, contrasting with only 2 cases of PCV13 serotypes during the seven years of late implementation period. There were 2 cases in immunocompetent and well vaccinated children hospitalized for PP due to 14 and 3 serotypes. These findings demonstrate a significant reduction in IPD but on the other hand show remaining disease in children with complete vaccination, also reported in other studies after many years of PCVs implementation programs [19]. We observed a non-significant increase of non-PCV-ST in children, three of the 5 strains isolated were NVST 7B/C, 22 F and 15 B in the late implementation period.

This significant reduction in hospitalization in children and adults observed in BH due to pneumococcal diseases caused by serotypes covered by conjugate vaccines used in Uruguay may demonstrate the long term effects of children universal vaccination, similar to those observed in USA, Canada and European countries, with around a 90% of reduction in IPD disease burden due to VST among adults, showing that herd immunity can be achieved after around a decade of establishing a sustained childhood vaccination program [14].

In this population, we must take in account that IPD due to non-PCV13-ST were most frequent than those caused by PCV13 serotype in adults in the late implementation period between 2016 and 2022. At least 13 different non-PCV13-ST were identified in the post implementation period compared with 3 found in the pre implementation period, actually the most frequent were 8, 22F, 12F, and 9N ST. The significant NVST increase didn’t impact on the reduction of the discharge rate from IPD. The increase in IPD due to NVST observed in children and adults during the late implementation period is a phenomenon observed in other settings and countries [14,19]. In Uruguay, the surveillance of pneumococcal pneumonia demonstrates a significant reduction in the disease burden in children. A remaining disease caused by non-PCV13-ST and vaccine ST like 3 and 1 was observed. In the case of ST 3 in immunocompetent patients the phenomena in partis associated with immunological characteristics of the capsular polysaccharide [6,26-28]. Mortality reduction is one of the most important results from this study.

The findings in this population related to the proportional increase in non-PCV13-ST may be useful to evaluate the potential benefit of PCVs 15 and 20 serotypes, actually introduced in North America and in European countries [29,30]. Our study has several limitations because of the characteristics of a descriptive study, that can be considered an ecological study. Data included refers only to patients with IPD diagnosis confirmed by S. pneumoniae isolation from blood or another sterile site. Information was not complete for all patients, including PCV vaccination status, especially for adult population. The strength of the study lies on the long-term surveillance period of 16 years performed by the investigation group, without changes in microbiological and clinical diagnosis.

The impact in morbidity, mortality, antimicrobial resistance and herd effect is some of the benefits well demonstrated after children universal vaccination with PCVs. The results from our study contribute in some way to the knowledge development about pneumococcal diseases prevention and also on direct and indirect effects of PCVs [14,20,29-31]. Eventually this information will be useful for the evaluation of PCVs with broad coverage in our country [32,33].

Conclusion

In this population a significant reduction in IPD hospitalization rates was observed in children (-92%) and also in adults (-65%). Some of these changes may be attribute to a strong herd effect. This conclusion is based in the significant decline of PCV13 serotypes isolated in children and adults comparing the period prior PCV with the late post implementation period, accompanied with significant reduction in mortality for IPD. An increase in the number of non-vaccine serotypes isolated from patients with IPD was observed specially in adults. Vaccination should be improved in the adult population, and with greater demand in immunosuppressed patients.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Authors contributions:

The authors contributed equally to this work.

References

- Wahl B, O'Brien KL, Greenbaum A, Majumder A, Liu L, et al. (2018) Burden of Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae type B disease in children in the era of conjugate vaccines: global, regional, and national estimates for 2000-15. Lancet Glob Health 6(7): e744-e757.

- JJC Drijkoningen, GGU Rohde (2014) Pneumococcal infection in adults: burden of disease. Clin Microbiol Infect 20(Suppl 5): 45-51.

- Fleming-Dutra KE, Conklin L, Loo JD, Knoll MD, Park DE, et al. (2014) Systematic review of the effect of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine dosing schedules on vaccine-type nasopharyngeal carriage. Pediatr Infect Dis J 33(Suppl 2): 152-60.

- Lee GM, Kleinman K, Pelton S, Lipsitch M, Huang S, et al. (2017) Immunization, Antibiotic Use, and Pneumococcal Colonization Over a 15- Year Period. Pediatrics 140(5): e20170001.

- Uruguay, Ministerio de Salud Pú Dirección General de Salud. División Epidemiología. Certificado esquema de vacunación año 2008.

- Pírez MC, Machado K, Pujadas M, Assandri E, Badia F, et al. (2020) Experiencia de una Unidad Medico quirúrgica en la prevención y tratamiento de adquirida en la comunidad y sus complicaciones en niños, en el marco del Sistema Nacional Integrado de Salud. Vol. 7: Suplemento 1 (2020): Premio Nacional de Medicina2019 Chapters 1 and 2 pages 12 to 20 ISSN: 2301-1254 AnfaMed.

- Campaña de nivelación con vacuna conjugada 13-valente. Uruguay, Ministerio de Salud Pú Dirección General de Salud. División Epidemiología.

- Coberturas de vacunación, Uruguay. Programa nacional operativo de inmunizaciones. [Comisión horaria de la lucha antituberculosas y enfermedades prevalentes.

- Inmunización en las Amé Resumen Año 2021. Coberturas inmunización reportadas."

- Pneumococccal conjugate vaccine 2008 to 2022.

- Campaña de vacunación antineumocócica 2015.

- Algorta G, Chiarella M, Sanchez Varela M, Firpo M, Bueno J, et al. Invasive pneumococcal disease in a general hospital. Hospitalization changes after the implementation of the PCV 7/13 universal vaccination in children. British Hospital. Facultad de Medicina. Universidad de la Repú Montevideo - Uruguay ISPPD-0420 10th International Symposium Pneumococcus and Pneumococcal Diseases, 2016 Glasgow, Scotland.

- Pírez MC, Mota MI, Giachetto G, Sánchez Varela M, Galazka J, et al. (2017) Pneumococcal Meningitis Before and After Universal Vaccination with Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines 7/13, Impact on Pediatric Hospitalization in Public and Nonpublic Institutions, in Uruguay. Pediatr Infect Dis J 36(10): 1000-1001.

- Shiri T, Datta S, Madan J, Tsertsvadze A, Royle P, et al. (2017) Indirect effects of childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive pneumococcal disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Glob Health 5(1): e51-e59.

- García Gabarrot G, López Vega M, Pérez Giffoni G, Hernández S, Cardinal P, et al. (2014) Effect of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccination in Uruguay, a Middle-Income Country. PLoS One 9(11): e112337.

- Hortal M, Estevan M, Meny M, Iraola I, Laurani H (2014) Impact of Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccines on the Incidence of Pneumonia in Hospitalized Children after Five Years of Its Introduction in Uruguay. PLoS One 9(6): e98567.

- Pírez MC, Algorta G, Chamorro F, Romero C, Varela A, et al. (2014) Changes in hospitalizations for pneumonia after universal vaccination with pneumococcal conjugate vaccines 7/13 valent and H. influenzae type b conjugate vaccine in a pediatric referral hospital in Uruguay. Pediatr Infect Dis J 33(7): 753-759.

- Lopardo GD, Fridman D, Raimondo E, Albornoz H, Lopardo A, et al. (2018) Incidence rate of community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based prospective active surveillance study in three cities in South America. BMJ Open 8(4): e019439.

- Kaplan SL, Barson WJ, Lin PL, Philana LL, José R, et al. (2019) Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in Children’s Hospitals: 2014–2017. Pediatrics 144(3): e20190567.

- Hanquet G, Krizova P, Valentiner-Branth P, Shamez NL, JP Nuorti, et al. (2019) Effect of childhood pneumococcal conjugate vaccination on invasive disease in older adults of 10 European countries: implications for adult vaccination. Thorax 74(5): 473-482.

- Bertran M, Amin-Chowdhury Z, Sheppard CL, Eletu S, Zamarreño DV, et al. (2022) Increased Incidence of Invasive Pneumococcal Disease among Children after COVID-19 Pandemic, England. Emerg Infect Dis 28(8): 1669-1672.

- Danino D, Ben-Shimol S, van der Beek BA, Givon-Lavi N, Avni YS, et al. (2022) Decline in Pneumococcal Disease in Young Children During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic in Israel Associated with Suppression of Seasonal Respiratory Viruses, Despite Persistent Pneumococcal Carriage: A Prospective Cohort Study. Clin Infect Dis 75(1): e1154-e1164.

- (2021) Weekly Influenza Report EW 49 Update: Influenza & Other Respiratory.

- Delfino M, Méndez AP, Pujadas Ferrer M, Pírez MC (2023)1320. Pneumococcal Meningitis Before and During Covid – 19 Pandemic in Uruguay, South America (2017-2022). Open Forum Infectious Diseases 10(Suppl 2): ofad500.1159.

- Bazzino F, Pirez MC, de los Ángeles T, Monteiro M, Acosta E, et al. (2023). Role of the Honorary Commission for the Fight Against Tuberculosis and Prevalent Diseases in the National COVID-19 Vaccination Strategy in Uruguay. Period November 2020 - July 2021. Archives of Pediatrics of Uruguay 94(1): e209.

- Machado K, Badía F, Assandri E, Gutiérrez C, Motta Inés, et al. (2020) Necrotizing pneumonia in children: 10 years of experience in a Pediatric Reference Hospital. Archives of Pediatrics of Uruguay 91(5): 294-302.

- Lemaître C, Angoulvant F, Gabor F, Makhoul J, Bonacorsi S, et al. (2013) Necrotizing pneumonia in children: report of 41 cases between 2006 and 2011 in a French tertiary care center. Pediatr Infect Dis J 32(10): 1146-1149.

- Luck JN, Tettelin H, Orihuela CJ (2020) Sugar-Coated Killer: Serotype 3 Pneumococcal Disease. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10: 613287.

- Hays C, Vermee Q, Agathine A, Dupuis A, Varon E, et al. (2017) Demonstration of the herd effect in adults after the implementation of pneumococcal vaccination with PCV13 in children. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 36(5): 831-838.

- Pelton SI, Bornheimer R, Doroff R, Shea KM, Sato R, et al. (2019) Decline in Pneumococcal Disease Attenuated in Older Adults and Those with Comorbidities Following Universal Childhood PCV13 Immunization. Clin Infect Dis 68(11): 1831-1838.

- Perdrizet J, Horn EK, Hayford K, Grant L, Barry R, et al. (2023) Historical Population-Level Impact of Infant 13-Valent Pneumococcal Conjugate Vaccine (PCV13) National Immunization Programs on Invasive Pneumococcal Disease in Australia, Canada, England and Wales, Israel, and the United States. Infect Dis Ther 12(5): 1351-1364.

- Lansbury L, Lawrence H, McKeever TM, French N, Aston S, et al. (2023) Pneumococcal serotypes and risk factors in adult community-acquired pneumonia 2018-20; a multicentre UK cohort study. Lancet Reg Health Eur 37: 100812.

- De Wals P (2024) PCV13, PCV15 or PCV20: Which vaccine is best for children in terms of immunogenicity? Can Commun Dis Rep 50(1-2): 35-39.