A Targeted Screening of Cardiac Arrhythmias in Stable COPD Patients

Asma Saidane1,2*, Haifa Zaibi1,2, Emna Ben Jemia1,2, Hend Ouertani1,2, Manel Ben Halima2,3 and Ben Amar Jihen1,2

1Department of Pneumology, Charles Nicolle Hospital, Tunisia

2University of Medicine, University of Tunis El Manar, Tunisia

3Department of Cardiology, Rabta Hospital, Tunisia

Submission: June 13, 2025; Published: June 27, 2025

*Corresponding author: Asma Saidane, Pneumology Department, Charles Nicolle Hospital, University of Medicine, University of Tunis El Manar, Tunis, Tunisia

How to cite this article: Asma Saidane, Haifa Zaibi, Emna Ben Jemia, Hend Ouertani, Manel Ben Halima and Ben Amar Jihen,et.al. A Targeted Screening of Cardiac Arrhythmias in Stable COPD Patients. Int J Pul & Res Sci. 2025; 7(5): 555725.DOI: 10.19080/IJOPRS.2025.07.555725

Abstract

Background

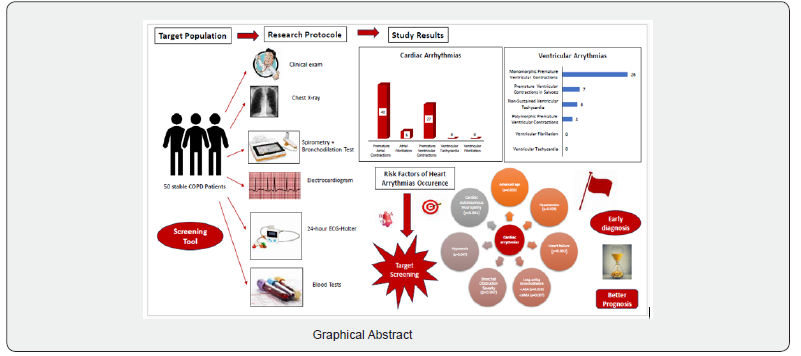

The chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) is actually recognized as a systemic disease often associated with a wide spectrum of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. The occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias may result in a poor prognosis. We aimed to estimate their prevalence in these patients as well as to identify the main risk factors.

Methods

We conducted a prospective, including stable COPD patients, followed-up in our department of Pneumology in the Charles Nicolle hospital, in collaboration with the interventional Cardiology department of the Rabta hospital during two years. The included patients had a thorough clinical examination, blood tests, an electrocardiogram, a chest X-ray, a spirometry, an echocardiography and a rhythmic holter.

Results

We included 50 patients with a mean age of 65 years. The main cardiovascular diseases reported in our study were: the ischemic heart diseases (18%), hypertension (16%), type 2 diabetes (24%) and dyslipidemia (6%). The rhythmic Holter findings revealed cardiac arrhythmias in 28% of the included patients. From which, atrial fibrillation was detected in 12% of cases, supraventricular premature contractions in 84% of cases, ventricular premature contractions in 54% of cases and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia in 12% of cases. We noticed monomorphic premature ventricular contractions in 54% of patients, polymorphic premature ventricular contractions in 8% of patients and salvoes of premature ventricular contractions in 14% of patients. The heart rate variability analysis revealed decreased values of both pNN50 (the proportion of the differences of more than 50 milliseconds between the successive R-R intervals) (p<0.001) and RMSSD (Root Mean Square of the Successive Differences between the successive R-R intervals) (p<0.001).The main risk factors of occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias were: an advanced age (p=0.003), associated cardiovascular comorbidities (hypertension (p=0.029), ischemic heart disease (p=0.002)), the severity of the bronchial obstruction (p<0.001), hypoxemia (p=0.047), the cardiac autonomic dysfunction (RMSSD (p<0.001)) and an associated pulmonary hypertension (p=0.046).

Conclusion

Cardiac arrhythmias are common in stable COPD patients. The identification of the risk factors of their occurrence would allow us to establish most appropriate decisional algorithms for a targeted screening strategy (Graphical Abstract).

Keywords:Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; Comorbidities; Heart arrhythmias; Screening; Prevalence; Prognosis

Abbreviations:COPD: Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease; ESC: European Society of Cardiology; PAC: Premature Atrial Contractions; PVC: Premature Ventricular Contractions; HRV: Heart Rate Variability; COPE : Committee on Publication Ethics; SD: Standard-Deviations; LABA: Long-Acting Bronchodilators

Introduction

COPD is actually recognized as a systemic disease often associated with a wide spectrum of cardiovascular and metabolic diseases. The occurrence of cardiac arrhythmias represented a turning point in the natural history of this disease [1,2]. In fact, it may lead to thromboembolic complications, heart failure or sudden death. Recent studies reported a very high prevalence of sudden death among these patients reaching 26% according to the TORCH trial and 18% based on the LIPLIFT study mainly due to the cardiac comorbidities [3]. Thus, heart arrhythmias screening is highly recommended by the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) [4]. It is very challenging especially in our developing countries. However, we still don’t have clear recommendations regarding the cardiac arrhythmias screening tools, the risk stratification as well as the follow-up suitable to these COPD patients. Indeed, epidemiological studies about the cardiac arrhythmias frequency in these cases remain rare in Tunisia. We aimed to assess the heart arrhythmias prevalence in stable COPD patients. We also tried to find out the main risk factors of their occurrence in this study group for a Targeted screening.

Methods

We conducted a prospective, observational study including 50 stable COPD patients confirmed with a spirometry, willing to participate to our research study, followed-up in our Pneumology department in Charles Nicolle hospital in Tunis in collaboration with the Interventional Cardiology department of the Rabta Hospital during a period of 2 years (from January 2019 up to December 2020). Patients presenting a serious worsening of their general state (Performants status=3 or 4), a recent acute COPD exacerbation (<15 days), an acute respiratory failure, an acute heart failure, a cardiomyopathy (dilated, hypertrophic, obstructive), congenital heart disease, a severe valvopathy or severe psychiatric disorders (psychosis) were not included. We also excluded the patients with missing data or refusing to participate to our study or to adhere to our Research Protocol. Indeed, we tried to avoid most of the confounding factors that may interfere with the arrhythmogenesis such as severe electrolyte disturbances like hyperkalemia, marked blood gas disturbances such as respiratory acidosis (PH<7.38), severe hypoxemia (PaO2 < 60 mmHg), hypercapnia (PaCO2>>50mmHg) or a deep anemia ((Hb<7g/dl) in patients affected with coronary heart disease or (Hb<10g/dl) in non-coronary patients.

The included patients had a thorough clinical exam, an electrocardiogram, a chest X-ray, blood gas tests, a spirometry with a bronchodilation test, a 24-hour ECG-holter and a two-dimensional echocardiography [5].

The « frequent exacerbator» clinical phenotype is defined by the occurrence of at least two COPD exacerbations during the previous year [1]. The patients were classified into four categories according to their body mass index (BMI) (underweight (BMI<18,5 Kg/m2), healthy weight (BMI 18,5- 24,9 Kg/m2), overweight (BMI (25- 29,9 Kg/m2) and obesity (BMI (>= 30 Kg/m2). We divided the cardiac arrhythmias into atrial arrhythmias (premature atrial contractions (PACs), atrial fibrillation or an atrial flutter) and ventricular arrhythmias (ventricular premature contractions (PVCs), ventricular tachycardia or ventricular fibrillation) [6,7]. Besides, we performed a temporal analysis of the heart rate variability (HRV) which represents the temporal intervals fluctuation between the successive cardiac contractions. It reflects the information’s transfer between the heart and the autonomic nervous system. Therefore, a heart twit regular beats that responds poorly to the external stimuli is exposed to a higher risk of cardiac arrhythmias and sudden death.

A reduced Heart rate variability (HRV) reflects indirectly an autonomic nervous system dysfunction marked by a vago-sympathetic balance disturbances with a significant reduction of the vagal tone and a predominant sympathetic activity. We were based on the following HRV parameters as recommended by the Task Force:

a) The p NN50: The percentage of the differences of more than 50msec between the successive R-R intervals measured by a 24-hour ECG-holter. It is strongly associated with the respiratory rate. Thus, its measure may be overestimated due to the respiratory sinusal arrhythmias given that these COPD patients have often a polypnoea.

b) RMSSD: Corresponds to the square root of the mean square R-R intervals differences. It reflects the vagal tone. Its measure is preferred rather than that of the SDNN and of the p NN50 because it has better statistical properties.

c) The SDNN: Corresponds to the standard deviation of the normal R-R intervals during 24 hours. Its exact measure requires the premature ventricular contractions and artefacts exclusion as well as a continuous ECG monitoring during at least 18-24 hours which make its measure less relevant for the autonomic nervous dysfunction assessment [8].

Then, we compared the measured HRV values to those of healthy individuals adjusted to the age and to the gender, as shown in the supplementary table [9].

Ethical approval

This study was conducted in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration principles and with the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) Guidelines. The ethical committee approved our research protocol (decision number: FWA 00032748, IORG 0011243). An informed consent was obtained from the patients.

The statistical analysis

The patients data were collected in an electronic database. We used a recent SPSS (Statistical Package for the Social Science) version (26th) for the data analysis. We conducted a descriptive and a comparative study. The numerical variables were represented as means, medians and standard-deviations (SD). We used the Fisher and Khi-deux tests in the case of qualitative variables. Whereas, the Student and the Mann-Whitney tests were used in quantitative variables. Indeed, the ANOVA and Kruskal-Walis tests were applied in multimodal variables. We also tried to find out the main prognostic determinants associated with the risk of cardiac arrhythmias occurrence in these patients based on a multivariate analysis. The Pearson and Spearman tests were used in order to establish the association between the quantitative variables. The results were considered as significant if the p value<0.05.

Results

Results

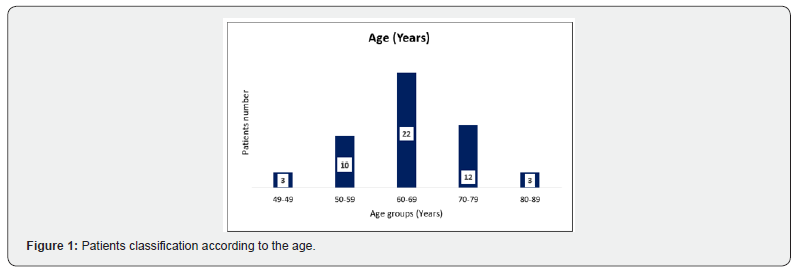

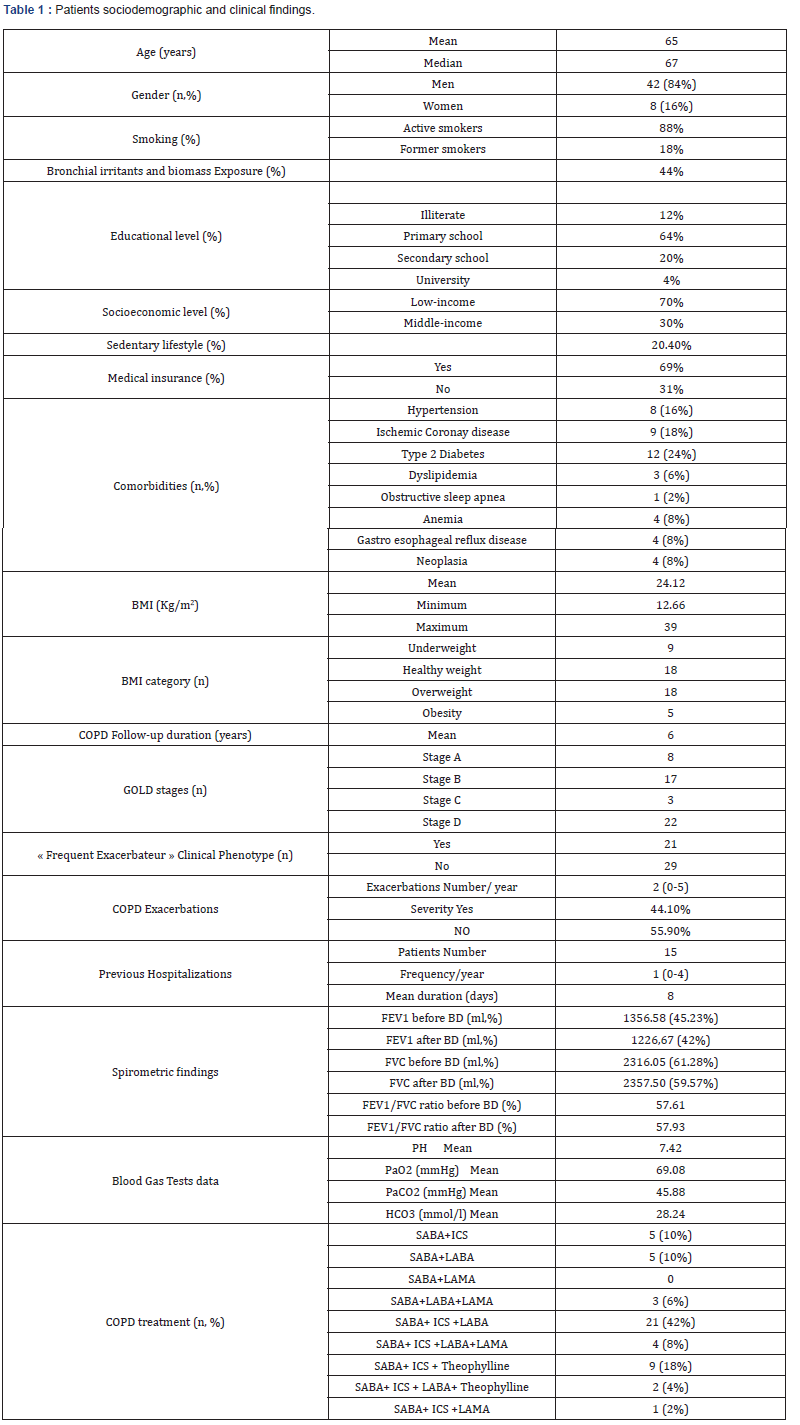

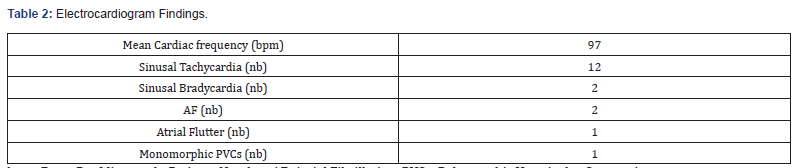

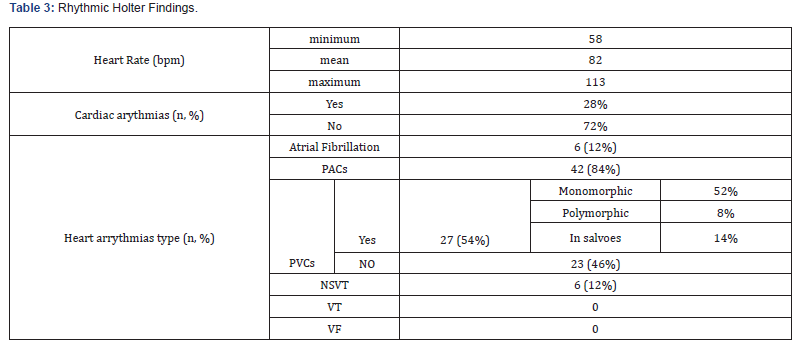

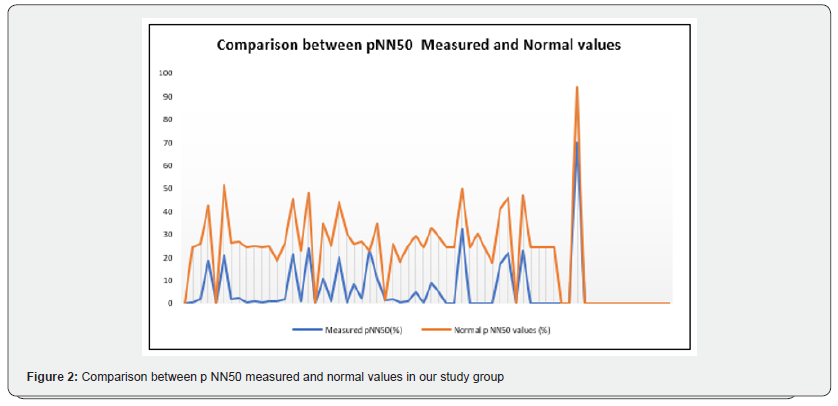

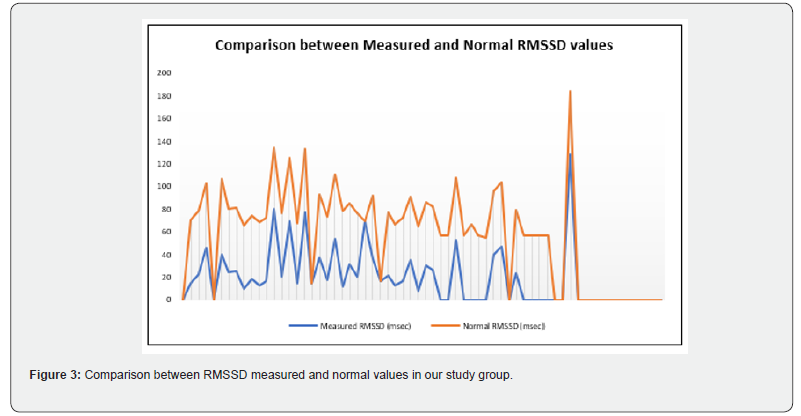

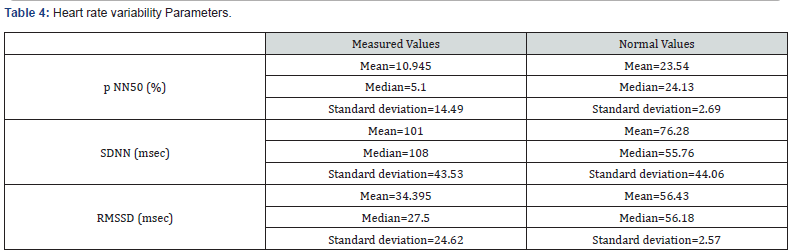

Our study enrolled 50 stable COPD patients mainly of men (42 men (84%), 8 women (16%)), with a gender-ratio of 5.25. The mean age of the included patients was 65 years (ranging from 46 years up to 85 years), as shown in the Figure 1 below. Most of them were active smokers (88%). We noticed that only (18%) of them weaned from tobacco smoking. Most of them came from very poor socioeconomic levels (70%). Cardiovascular comorbidities were reported in (44%) of the included cases mainly ischemic heart disease in (18%), hypertension (16%), type 2 diabetes (24%) and dyslipidemia (6%), as shown in Table 1. The « frequent exacerbator» clinical phenotype had been reported in 21 cases. Concerning the COPD severity assessment, 8 patients were ranged in GOLD stage A, 17 patients in GOLD stage B, 3 patients in GOLD stage C and 22 patients in GOLD stage D. The electrocardiogram revealed an atrial fibrillation in two patients and an atrial flutter in one patient. Besides, monomorphic premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) were noticed in one case, as shown in Table 2. Almost half of the included patients (52%) had an associated pulmonary hypertension according to the echocardiographic findings. The ECG-holter revealed cardiac arrhythmias in (28%) of the cases. Atrial fibrillation was reported in 12% of the patients, premature atrial contractions (84%), premature ventricular contractions (54%) and non-sustained ventricular tachycardia (12%), as shown in Table 3. As regards the HRV, the measured RMSSD and p NN50 values were much lower compared to the normal values with (p<0.001) each, as shown in the Figures 2 & 3 as well as in the Table 4 below.

BMI: Body Mass Index, n: Number, COPD: Chronic Obstructive Disease, FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume, BD: Bronchodilator, ml: Milliliters, FVC: Forced Vital Capacity, PH: Potential of Hydrogen, PaO2: Arterial Partial Pressure of Oxygen, PaCO2: Arterial Partial Pressure of Carbon Dioxide, HCO3: Bicarbonate Level, SABA: Short-Acting Bronchodilators, ICS: Inhaled Corticosteroids, LABA: Long-Acting Bronchodilators, LAMA: Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonist.

bpm: Beats Per Minute, nb: Patients Number, AF: Atrial Fibrillation, PVCs: Polymorphic Ventricular Contractions

bpm: beats per minute, AF : atrial fibrillation, PACs : premature atrial contractions, PVCs : premature ventricular contractions, , NSVT: non-sustained ventricular tachycardia, VT : ventricular tachycardia, VF : ventricular fibrillation

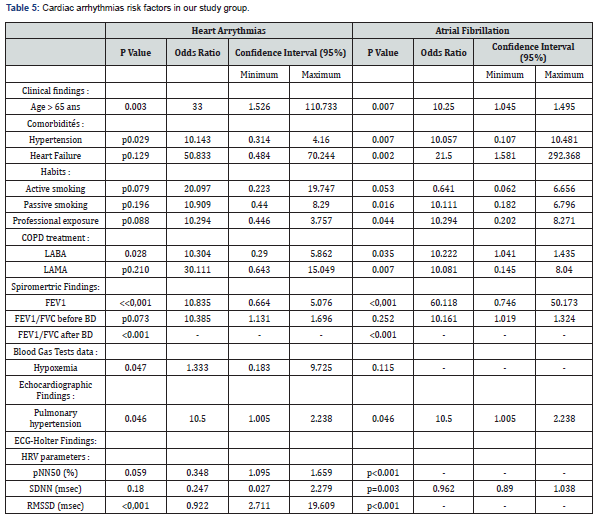

Concerning the multivariate analysis findings, the advanced age was associated with a higher risk of the heart arrhythmias occurrence in our study group (p=0.003). As regards the cardiac comorbidities, arrhythmias were common especially in patients affected with hypertension (p=0.029). Atrial fibrillation was more frequent in patients affected with coronary ischemic disease at the stage of heart failure (p=0.002). We also noticed a strong association between the bronchial obstruction severity and the risk of cardiac arrhythmias (p<0.001) according to our study results. Besides, arrhythmias were more common in stable patients with hypoxemia (p=0.047). Concerning the COPD daily treatment, the long-acting bronchodilators (LABA) use was strongly linked with a higher risk of cardiac arrhythmias (p=0.028). Indeed, the patients under a long-acting anti-cholinergic medication (LAMA) had an increased risk of atrial fibrillation (p=0.007) [10]. Moreover, arrhythmias were more common in patients with an associated pulmonary hypertension (p=0.046). Concerning the heart rhythm variability (HRV) assessment, reduced RMSSD was strongly linked to a higher risk of the cardiac arrythmias occurrence (p<0.001). Atrial fibrillation was more common in COPD patients with a cardiac autonomous neuropathy: pNN50 (p<0.001), RMSSD (p<0.001) and SDNN (p=0.003), as shown in Table 5.

AF: Atrial Fibrillation, FEV1: Forced Expiratory Volume, FVC: Forced Vital Capacity, LABA: Long-Acting Bronchodilators, LAMA: Long-Acting Muscarinic Antagonists, SABA: Short-Acting Bronchodilators, p NN50: the percentage of the differences of more than 50 msec between the successive R-R intervals, %: Percentage, SDNN: Standard Deviation of the R-R intervals, msec: Millisecondes, RMSSD: Root Mean Square of the Successive Differences between the successive R-R intervals.

Discussion

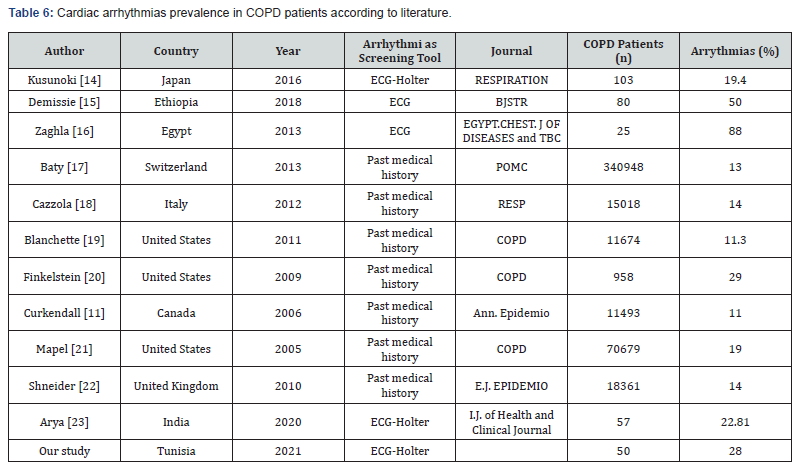

COPD is a very common respiratory disease due to a chronic persistent bronchial obstruction with an important death rate and socioeconomic burden [11]. It represents actually the third cause of disease-related death (7% of deaths) ranged after the cardiovascular diseases and cancer, with a significant increase of 18% since 1990 according to the latest WHO report [12]. It is often associated with a wide spectrum of cardiovascular comorbidities such as (ischemic cardiac disease, heart failure, arrhythmias) [13]. Cardiac arrhythmias were reported in 28% of the included patients according to our study results. We also noticed a high prevalence of the heart arrhythmias in most of the reported studies. In fact, a Canadian study published by Curkendall and al. including 11493 COPD patients highlighted a higher risk of arrhythmias among COPD patients compared to witness (OR=1.76) [14]. Besides, a British prospective cohort study published by Khurshid and al. based on the UK Biobank data including 502607 adults demonstrated that COPD was associated with an increased risk of arrhythmias (Odds ratio=1.5) [15].

Indeed, a recent review published by Iglesias and al. about « the management of the COPD comorbidities »in 2020 highlighted a high prevalence of cardiac arrhythmias ranging from 5% up to 15% in stable COPD patients reaching 30% in severe COPD cases [16]. However, it remains underestimated in these patients. In fact, most of the cohort studies were based on the patients past medical history findings collected from the electronic databases and not on a real cardiac arrhythmias screening. All the included COPD patients had a 24-hour ECG-holter monitoring in our study given that most of the heart rhythm disturbances occurred at night and may be to the nocturnal hypoxemia. The Table 6 below illustrated the heterogeneity of the published studies data mainly due to differences of the research protocols methodology, the inclusion criteria, the population study characteristics as well as the cardiac arrythmias screening tools.

ECG: Electrocardiogram, n: number, BJSTR: Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research, EGYPT.CHEST. J OF DISEASES and TBC: Egyptian Journal of Chest Diseases and Tuberculosis, Resp: Respiration, Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis: Internal Journal of Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease, Ann. Epidemio.J: Annals of Epidemiology Journal, I.J. of Health and Clinical Journal: International Journal of Health and Clinical Research.

Two main hypotheses may explain the high prevalence of the cardiac arrhythmias in COPD patients. According to the first hypothesis known as « Electro Pathy Hypothesis », when the myocardial cells are exposed to particular conditions such as (hypoxemia, hypercapnia, hyperkaliemia), they may acquire an automatism that they are normally deprived from [17]. Thus, arrhythmias result from an abnormal depolarization of the myocardial cells. Recent studies demonstrated that the chronic gas exchange disturbances like (hypoxemia, hypercapnia, respiratory acidosis) ;often reported among COPD patients ; may increase the myocardial electrical heterogeneity leading to heart arrhythmias [18].

Whereas, the second hypothesis suggested that the cardiac autonomous neuropathy as the main underlying mechanism of arrythmias occurrence in these COPD patients [19,20]. It is may be due to the chronic hypoxemia or to the natural history of COPD. Recent studies suggested the HRV assessment as an accurate and non-invasive tool based on an ECG-Holter monitoring in order to assess the autonomic nervous system dysfunction. It is actually recognized as a prognostic marker in many pathological conditions such as (myocardial infarction, diabetes, acute fetal distress, Parkinson disease, dementia) predicting the occurrence of heart arrythmias and cardiac sudden death as shown in our study [21-28]. In fact, we noticed reduced HRV among COPD patients were much lower than the normal values (RMSSD (p<0.001), pNN50 (p<0.001)). A prospective study published by Kong and al. including 151 COPD patients and 45 witness reported reduced HRV values in the observational group compared to those of the control group (p<0.001) [19].

Thus, the authors supported the second hypothesis. The same findings were reported in a recent study, including 48 COPD patients and 54 healthy individuals as controls, published in 2022. The researchers noticed reduced HRV values in both time and frequency domains according to the ECG-Holter data. In fact, the HRV high frequency (HF) component which reflects a reduced parasympathetic tone was much lower in COPD patients (p=0.033). Whereas, the low frequency (LF) component which is strongly linked to the sympathetic tone as well as the (LF/HF) ratio were higher in the observational group compared to those of the control group, with (p=0.033) each. The predominant sympathetic activity during the nychthemeral (even at night) unlike healthy individuals would be linked to an increased risk of heart arrhythmias and cardiac sudden death in these cases [29].

It is worth mentioning that the Cardiac autonomous neuropathy may exist in all COPD stages as reported in our study. The same findings were noticed in a prospective including 56 COPD cases and 11 controls published by Chabra and al. in 2005. In fact, the authors demonstrated an autonomic nervous system dysfunction in mild COPD patients even though it tended to be more common in moderate to severe COPD patients (without any significant difference). Thus, they concluded that the cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy developed progressively and gradually regardless the bronchial obstruction severity [30]. Recent studies revealed that the cardiovascular comorbidities such as (heart failure, arrhythmias, ischemic cardiac disease) are the most common cause of sudden death among these COPD patients [31]. In fact, they resulted in about 30% of the death rate in these cases [32]. In fact, a prospective national cohort study published by Lahousse al. in Netherlands ; including 14926 adults ; suggested that COPD was associated to a higher risk of cardiac sudden death (odds ratio=1.34). Indeed, researchers noticed that cardiac arrhythmias occurred mainly at night in these cases may be due to the nocturnal hypoxemia [33].

The cardiac arrhythmias risk factors reported in our study were mainly: an advanced age, associated cardiovascular comorbidities (heart failure, hypertension), the bronchial obstruction severity, hypoxemia, the autonomic nervous system dysfunction and an associated pulmonary hypertension. An updated review published in 2024 suggested that the prognostic factors associated with the arrhythmias occurrence in stable COPD patients are : an advanced age, the ischemic cardiac disease, the autonomic nervous system, hypoxemia and the long-term use of long-acting bronchodilators [34]. Therefore, the heart arrythmias risk factors identification would allow us to establish appropriate decisional algorithms based on an accurate risk stratification for a precision medicine. Our study had some limits. We included a small number of COPD patients given the lack of the patients knowledge and awareness as well as the arrhythmias screening tools availability. We could not perform an echo cardio cardiography for some cases after the COVID Pandemic. Besides, we should have included a control group given that arrhythmias may exist even in healthy individuals (respiratory sinusal arrythmias).

Conclusion

Our study highlighted the importance of an early screening of the cardiac arrhythmias in COPD patients. The prognostic factors identification would allow us to establish accurate decisional algorithms based on a rigorous risk stratification for a predictive medicine. Further studies are still required in order to better understand the underlying mechanisms.

Declaration of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper. The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests.

References

- Palange P, Simonds AK (2013) ERS handbook of respiratory medicine. Paris: European Respiratory Society.

- Simons SO, Elliott A, Sastry M, Hendriks JM, Arzt M (2021) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and atrial fibrillation: an interdisciplinary perspective. Eur Heart J 42(5): 532-540.

- André S, Conde B, Fragoso E, Boléo Tomé JP, Areias V (2019) COPD and cardiovascular disease. Pulmonology 25(3): 168-176.

- Natali D, Cloatre G, Hovette P, Cochrane B (2020) Screening for comorbidities in COPD. Breathe 16(1): 190315.

- Zulfiqar AA (2020) Frailty syndrome: a major concept in the prevention of geriatric syndromes. Rev Med Liege 75(12): 816-821.

- Beaumont JL (2017) Cardiac arrhythmias: a clinical and therapeutic guide. (7th edn). Canada: Cheneliè

- Fuster V, Harrington RA, Narula J, Eapen ZJ (2017) Hurst’s the heart. (14th edn). New York: Mc Graw Hill Education.

- Abeer I (2012) Interest of heart rate variability as a risk marker [thesis: medicine]. Lille: University of Law and Health.

- Bauer A, Camm A, Cerutti S, Guzik P, Huikuri H (2017) Reference values of heart rate variability. Heart Rhythm 14(2): 302-303.

- Lang RM, Badano LP, Mor Avi V, Afilalo J, Armstrong A (2015) Recommendations for cardiac chamber quantification by echocardiography in adults: an update from the American society of echocardiography and the European association of cardiovascular imaging. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 28(1): 1-39.

- Venkatesan P (2023) Gold COPD report: 2023 update. Lancet Respir Med 11(1): 18.

- Soriano JB, Kendrick P, Paulson K, Gupta V, Vos T (2020) Prevalence and attributable health burden of chronic respiratory diseases, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Respir Med 8(6): 585-596.

- Roversi S, Fabbri L, Sin D, Hawkins N, Agust A (2016) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and cardiac diseases. An urgent need for integrated care. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 194(11): 1319-1336.

- Curkendall SM , De Luise C, Jones JK, Lanes S, Stang MR (2006) Cardiovascular disease in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, Saskatchewan Canada: cardiovascular disease in COPD patients. Ann Epidemiol 16(1): 63-70.

- Khurshid S, Choi SH, Weng LC, Wang EY, Trinquart L, et al. (2018) Frequency of cardiac rhythm abnormalities in a half million adults. Circ Ar rhythm Electro Physiol 11(7): e006273.

- Iglesias JR, DíezManglano J, López García F, Díaz Peromingo JA, Almagro P (2020) Management of the COPD patient with comorbidities: an experts recommendation document. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 15: 1015-1037.

- Bertrand M, Bourdarias JP, Broustet JP, Cherrier F, Clement D (1982) Cardiopulmonary physio-pathology. Villeurbanne: Simep.

- Zaghla H, Al Atroush H, Samir A, Kamal M (2013) Arrhythmias in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Egypt J Chest Dis Tuberc 62(3): 377‑3

- Kong ZB, Wang XD, Shen SR, Liu H, Zhou L, et al. (2020) Risk prediction for arrhythmias by heart rate deceleration runs in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 15: 585-593.

- Scalvini S, Porta R, Zanelli E, Volterrani M, Vitacca M (1999) Effects of oxygen on autonomic nervous system dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Eur Respir J 13(1): 119-124.

- Dias De Carvalho TC, Marcelo P, Rossi RC, De Abreu LC, Valenti VE (2011) Geometric indices of heart rate variability in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Rev Port Pneumol 17(6): 260-265.

- Pieper SJ, Hammill SC (1995) Heart rate variability: technique and investigational applications in cardiovascular medicine. Mayo Clin Proc 70(10): 955-964.

- Goldenberg I , Goldkorn R, Shlomo N , Einhorn M, Levitan J (2019) Heart rate variability for risk assessment of myocardial ischemia in patients without known coronary artery disease: the HRV-DETECT (heart rate variability for the detection of myocardial ischemia) study. J Am Heart Assoc 8(24): e014540.

- Catai AM, Pastre CM, Godoy MF, Silva E, Takahashi AC (2020) Heart rate variability: are you using it properly? Standardization checklist of procedures. Braz J Phys Ther 24(2): 91-102.

- Yugar LT, Yugar Toledo JC, Dinamarco N, Sedenho Prado LG (2023) The role of heart rate variability (HRV) in different hypertensive syndromes. Diagnostics 13(4): 785.

- Laborde S, Mosley E, Bellenger C, Thayer J (2022) Editorial: horizon 2030: innovative applications of heart rate variability. Front Neurosci 16: 937086.

- Peabody JE, Ryznar R, Ziesmann MT, Gillman L (2023) A systematic review of heart rate variability as a measure of stress in medical professionals. Cureus 15(1): e34345.

- Arakaki X, Arechavala R, Choy EH, Bautista J, Bliss B (2023) The connection between heart rate variability (HRV), neurological health, and cognition: a literature review. Front Neurosci 17: 1055445.

- Das M, Mitra K, Banerjee T (2023) Study of heart rate variability to assess autonomic dysfunction in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease of a tertiary care hospital of West Bengal: a cross-sectional comparative study. Natl J Physiol Pharm Pharmacol 13(3): 485-489.

- Chabra SK, De S (2005) Cardiovascular autonomic neuropathy in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Respir Med 99(1): 126-133.

- Desai R, Patel U, Singh S, Bhuva R, Fong HK (2019) The burden and impact of arrhythmia in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: insights from the national inpatient sample. Int J Cardiol 281: 49-55.

- Albert CM, Stevenson WG (2016) The future of cardiovascular biomedicine: arrhythmias and electrophysiology. Circulation 133(25): 2687-2696.

- Lahousse L, Niemeijer MN, Van Den Berg ME, Rijnbeek PR, Joos GF (2015) Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and sudden cardiac death: the Rotterdam study. Eur Heart J 36(27): 1754-1761.

- Minai OA, Madias C (2023) Arrhythmias in COPD.