A Case of Systemic Sclerosis with ILD and Pulmonary Tuberculosis - A Rare Case Report

Amit Goyal1*, Kajal NC2, Amanpreet Kaur1

1Department of TB and Chest, Government Medical College, India

2Department of TB and Chest, Government Medical College, India

Submission: July 13, 2019 Published: August 08, 2019

*Corresponding author: Amit Goyal, Department of,Chest and TB Department, Junior Resident, Government Medical College, Amritsar, India

How to cite this article: Amit Goyal, Kajal NC, Amanpreet Kaur. A Case of Systemic Sclerosis with ILD and Pulmonary Tuberculosis - A Rare Case Report. Int J Pul & Res Sci. 2018; 4(1): 555629. DOI: 10.19080/IJOPRS.2019.04.555629

Abstract

LCSSC: Limited Cutaneous Sclerosis; DCSSC: Diffuse Cutaneous Sclerosis; SSC: Systemic Sclerosis; ILD: Interstitial Lung Disease; PH: Pulmonary Hypertension; PFTs Pulmonary Function Tests; HRCT: High-Resolution Computed Tomography; PFTs: Pulmonary Function Tests; BAL: Bronchoalveolar Lavage; NSIP: Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonitis

Introduction

Systemic scleroderma is an autoimmune disorder that affects the skin and internal organs. Autoimmune disorders occur when the immune system malfunctions and attacks the body’s own tissues and organs. The word “scleroderma” means hard skin in Greek, and the condition is characterized by the buildup of scar tissue (fibrosis) in the skin and other organs. The condition is also called systemic sclerosis because the fibrosis can affect organs other than the skin. Fibrosis is due to the excess production of a tough protein called collagen, which normally strengthens and supports connective tissues throughout the body. The classification of SSC is subdivided based on the extent of skin involvement into Diffuse Cutaneous Sclerosis (DCSSC), Limited Cutaneous Sclerosis (LCSSC) or SSC sine scleroderma [1]. Early sign of systemic scleroderma is puffy or swollen hands before thickening and hardening of the skin due to fibrosis. Fibrosis can also affect internal organs and can lead to impairment or failure of the affected organs. The most commonly affected organs are the esophagus, heart, lungs, and kidneys. Pulmonary involvement is common in patients with Systemic Sclerosis (SSC), and this leads to substantial morbidity and mortality.

While virtually any organ system may be involved in the disease process, fibrotic and vascular pulmonary manifestations of SSC, including Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD) and Pulmonary Hypertension (PH), are the leading cause of death. In scleroderma, the two most common types of direct pulmonary involvement are ILD and PAH, which together account for 60% of SSC-related deaths [2]. ILD is common in scleroderma. In early autopsy studies, up to 100% of patients were found to have parenchymal involvement [3]. As many as 90% of patients will have interstitial abnormalities on High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT) [4] and 40-75% will have changes in Pulmonary Function Tests (PFTs) [5]. Parenchymal lung involvement often appears early after the diagnosis of SSC, with 25% of patients developing clinically significant lung

disease within 3yrs as defined by physiological, radiographic or Bronchoalveolar Lavage (BAL) abnormalities. Disrupted immunity from the disease or associated medication may render such patients subject to tuberculosis infection. Infections are also known to induce the development of auto antibodies. A rare case of SSC, simultaneous diagnosis of ILD and pulmonary tuberculosis is being reported here.

Case Report

A 58year old female presented with complaints of breathlessness on exertion (MMRC grade II), cough with expectoration, fever, loss of appetite, difficulty in swallowing and tightening of skin around the mouth and skin thickening bilaterally in hands. There was no history of chest pain, hemoptysis, and wheeze. There was no occupational exposure to chemicals, dust and smoke.

On examination, patient was moderate built. Patient had features of salt and pepper appearance, mask like face, pinched nose, facial melanosis, telangiectasia over the cheeks,sclerodactyly and resorption of digits (Figure 1) diagnostic of scleroderma. There was no pallor, cyanosis, clubbing, lymphadenopathy or pedal edema. Pulse was 110/min and BP: 110/70mmhg. Respiratory examination revealed bilateral end inspiratory crackles of Velcro type and coarse crept over left suprascapular area. Other systems were normal.

Provisional diagnosis of systemic sclerosis with interstitial lung disease was made. Due to financial limitation and she was fitting into clinical ACR criteria [6] for diagnosis, ANA alone was sent as a part of autoimmune antibody profile which was positive, value is 5.18 (positive:>1.2), contributing towards the diagnosis.

Further serological investigations revealed anemia with Hb of 8.1gm%, elevated leukocyte count with70% polymorphs and elevated ESR-55mm. Renal and liver functions were within normal limits. HIV serology was Non-reactive

Chest X-ray (Figure 2) revealed thick walled cavity in the left upper lobe and increased reticular opacities bilaterally. In view of thick walled cavity, secondary infections due to bacterial, fungal and tuberculous organisms were considered. Her sputum examination for AFB came out to be 3+ and MTB is detected on CBNAAT the gram stain, cultures revealed no growth.

The skin biopsy was done and histopathlogy report shows epidermal thickening beneath which bundles of thick collagen are seen along with adenexal structures and theses features suggestive of sytemic sclerosis.

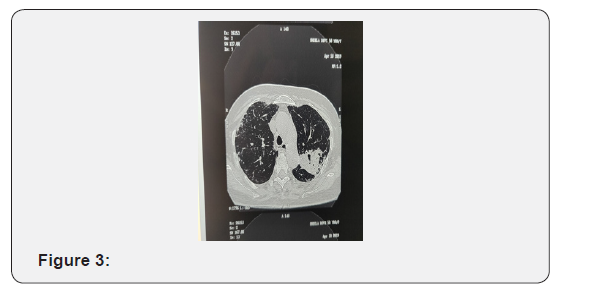

HRCT chest (Figure 3) showed a Soft tissue density lesion with Fibro-cavitory lesion in the Apico-posterior Segment of Left Upper Lobe-Likely collapse or consolidation with honeycombing and Interstitial Thickening involving Interlobular, Centrilobular and peribronchovascular Intertitium involving both lungs fields and calcified lymph nodes at bilateral Hilar region likely ILD. So, she had features of both progressive ILD and active pulmonary tuberculosis. Patient was initiated on anti tuberculous drugs as per RNTCP Guidelines and treatment for ILD after 1month of antituberculous treatment.

Discussion

Systemic sclerosis is a multisystem disease involving skin, lungs, kidneys, heart, GI tract and skeletal muscles. Incidence is three times more in women than in men with the peak incidence between ages 20-60. Pulmonary involvement in the form of interstitial lung disease is common in patients with Systemic Sclerosis (SSC).

Systemic Sclerosis (SSC) has the highest cause-specific mortality of all of the connective tissue diseases. Although SSC often affects multiple organ systems, pulmonary involvement, and in particular Interstitial Lung Disease (ILD), is the leading cause of death [7]. ILD is present on High-Resolution Computed Tomography (HRCT) in 55% of patients with SSC on initial evaluation, but the prevalence is higher (96%) among patients with abnormal Pulmonary Function Test (PFT) results.

HRCT is the standard method for the noninvasive diagnosis of SSC-ILD and can detect mild abnormalities. The true incidence of HRCT abnormalities is difficult to determine, but the majority of patients (55-84%) will have disease and the extent is generally limited with an average of 13% of the parenchymal involved [8].

The most common form of ILD appreciated in SSC is Nonspecific Interstitial Pneumonitis (NSIP); however, other histopathological manifestations exist, including usual interstitial pneumonitis, organizing pneumonia, and diffuse alveolar damage [9]. Other modalities to confirm the diagnosis are PFT, BAL Cellular profile, Lung Biopsy.

The treatment of SSC-ILD is limited to targeting inflammatory pathways with corticosteroids or other immunosuppressive therapy. This therapeutic approach is largely empirical and parallels strategies historically used in treating idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and related disorders. Cyclophosphamide is currently the most studied immunosuppressive therapy in SSCILD However, the benefit of cyclophosphamide for this disease is tempered by its complex adverse event profile. More recent studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of Mycophenolate systemic sclerosis related ILD, including Scleroderma Lung study. Tashkin et al. [10] later compared treatment with Mycophenolate mofetil for 2-years versus cyclophosphamide for 1year. While they noted significant improvement in lung function, they were unable to confirm greater efficacy at 24 months with Mycophenolate mofetil despite its superior tolerability and toxicity profile [10].

Patients with autoimmune diseases are known to develop infections like tuberculosis either due to the disease activity or secondary to the immunosuppressive therapy. Tuberculosis per se is known to induce the development of autoantibodies which in turn stimulate the manifestation of autoimmune diseases [11]. Sreeram V Ramagopalan et al. [12] analyzed a database of statistical records of patients in England (1999 to 2011) and found a significant association of tuberculosis and autoimmune diseases. High levels of risk for tuberculosis was found in diseases like Addison’s disease, SLE, polymyositis and patients with scleroderma had a relative risk of 6.1 (95% CI 4.4 to 8.2). He also looked at the incidence of immune diseases after 5 years of first occurrence of tuberculosis and found significant increase in Addison’s disease, Sjogren’s and SLE. The possible mechanism for this association was tuberculosis being infective trigger acting by molecular mimicry, bystander activation or acting as an adjuvant.

Pradhan et al did a screening of auto antibodies in tuberculosis endemic areas and concluded a possible role of mycobacterial infection triggering autoimmunity. Importance of screening all tuberculosis patients for autoantibody profile and follow up for autoimmune related symptoms was highlighted [11].

In a similar previous case report by Agarwal et al. [13] in 1977 pulmonary tuberculosis was diagnosed in a known case of scleroderma who has taken systemic steroids for six months duration. In that case there was a possibility of Tuberculosis because of immunosuppression secondary to steroid therapy. Shachor et al. [14] suggests that a diffusely damaged lung increases the susceptibility to tuberculosis or activation of dormant tuberculosis [14].

Another study done by Subramanian et al. [15] highlights the association of tuberculosis and autoimmune diseases [15]. The present case was diagnosed to have interstitial lung disease and pulmonary tuberculosis concurrently and had characteristic features of systemic sclerosis.

Conclusion

Tuberculosis is endemic in India and physicians play a vital role in its control. This case is reported to highlight the association between Tuberculosis and immune-mediated diseases and to create the awareness regarding recognition of pulmonary manifestations of co-existent connective tissue disorders and tuberculosis. Awareness of association between the above combination and high index of suspicion based on clinical and radiological findings will help in early diagnosis and management of immune mediated diseases there by reducing the morbidity of the illness.

References

- Gabrielli A, Avvedimento EV, Krieg T (2009) Scleroderma. N Engl J Med 360(19): 1989-2003.

- Steen VD, Medsger TA (2007) Changes in causes of death in systemic sclerosis, 1972-2002. Ann Rheum Dis 66(7): 940-944.

- D'Angelo WA, Fries JF, Masi AT, Shulman LE (1969) Pathologic observations in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). A study of fifty-eight autopsy cases and fifty-eight matched controls. Am J Med 46(3): 428-440.

- Schurawitzki H, Stiglbauer R, Graninger W, Herold C, Pölzleitner D, et al. (1990) Interstitial lung disease in progressive systemic sclerosis: high-resolution CT versus radiography. Radiology 176(3): 755-759.

- Steen VD, Conte C, Owens GR (1994) Severe restrictive lung disease in systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 37(9): 1283-1289.

- Van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, Johnson SR, Baron M, et al. (2013) 2013 Classification Criteria for Systemic Sclerosis: An American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism Collaborative Initiative. Arthritis Rheum 65(11): 2737-2747.

- Elhai M, Meune C, Avouac J, Kahan A, Allanore Y (2012) Trends in mortality in patients with systemic sclerosis over 40 years: a systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Rheumatology (Oxford) 51(6): 1017-1026.

- Desai SR, Veeraraghavan S, Hansell DM, Nikolakopolou A, Goh NS, et al. (2004) CT features of lung disease in patients with systemic sclerosis: comparison with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and nonspecific interstitial pneumonia. Radiology 232(2): 560-567.

- Bouros D, Wells AU, Nicholson AG, Colby TV, Polychronopoulos V, et al. (2002) Histopathologic subsets of fibrosing alveolitis in patients with systemic sclerosis and their relationship to outcome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 165(12): 1581-1586.

- Tashkin DP, Roth MD, Clements PJ, Furst DE, Khanna D, et al. (2016) Mycophenolate mofetil versus oral cyclophosphamide in scleroderma-related interstitial lung disease (SLS II): a randomised controlled, double-blind, parallel group trial. Lancet Respir. Med 4(9): 708-719.

- Pradhan V, Patwardhan M, Athavale A, Taushid S, Ghosh K (2012) Mycobacterium tuberculosis triggers autoimmunity. Indian J Tuberc 59(1): 49-51.

- Ramagopalan SV, Goldacre R, Skingsley A, Conlon C, Goldacre MJ (2013) Associations between selected immune-mediated diseases and tuberculosis: record-linkage studies. BMC Med 97(11): 1741-7015.

- Agarwal MC, Mital OP, Govil MK, Kansal HM, Agarwal VK Coexisting scleroderma and pulmonary tuber.

- Shachor Y1, Schindler D, Siegal A, Lieberman D, Mikulski Y, et al. (1989) Increased incidence of pulmonary tuberculosis in Chronic interstitial lung disease. Thorax 44(2): 151-153.

- Subramanian S, Ragulan R, Natraj M, Meenakshi N, Viswambhar V (2015) Co-existence of scleroderma and Tuberculosis. Sch J Med Case Rep 3(1): 22-24.