Perforated Peptic Ulcer: A Post-Operative Case

Hassam Ali* and Shiza Sarfraz

Bahawal Victoria hospital Bahawalpur, Pakistan

Submission: September 08, 2018;Published: October 16, 2018

*Corresponding author: Hassam Ali, Bahawal Victoria hospital Bahawalpur, Pakistan

How to cite this article: Hassam A, Shiza S. Perforated Peptic Ulcer: A Post-Operative Case. Glob J Pharmaceu Sci. 2018; 6(2): 555685. DOI: 10.19080/GJPPS.2018.06.555685.

Abstract

Perforated Peptic ulcers are medical emergencies which have high mortality rate if untreated. Most important cause of peptic ulcers is the bacteria, Helicobacter pylori. Another because which is becoming more and more prevalent is use of pain medications, especially non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs also known as NSAIDs. This case report follows a patient who was a long-term user of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for his gallbladder pain and later with combined stress of operation had the complication of perforated peptic ulcer

Keywords: Ulcer; Peptic; Steroidal; Vomiting; Hemorrhagic

Introduction

Peptic ulcer disease (PUD) is a break in the lining of the stomach wall, first part of the small intestine that is, duodenum or occasionally the lower esophagus [1]. An ulcer in the stomach is known as a gastric ulcer and that in the first part of the intestines is known as a duodenal ulcer [1]. The most common symptoms a patient will experience for a duodenal ulcer is nocturnal pain and pain that improves with eating [1]. On the other hand, gastric ulcer presents with pain that increases with eating food [2]. Pain is dull or aching in nature [1]. Other symptoms include vomiting, weight loss, belching. Complications of peptic ulcers include, bleeding or even perforation which is far more serious [3].

Common culprits of peptic ulcer disease are bacteria Helicobacter pylori’s infection or excessive use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) [1]. Gastrointestinal bleeding is the most commonly occurring complication and this may be so excessive that patient may have hemorrhagic instability and might go into hypovolemic shock. Our patient was a similar case who was operated for cholelithiasis laparoscopically, he had a long history of NSAIDs use for gallbladder pain but was never diagnosed with peptic ulcers and he presented post operatively with signs of hypotension and shock. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Case Presentation

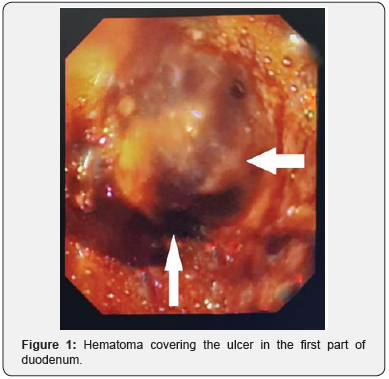

A fifty-year-old man was brought to emergency department with complaint of sweating, palpitations, decrease consciousness, fatigue and nausea. On clinical examination his pulse was rapid, and blood pressure was low i.e. 90/60 (systolic over diastolic). His skin was cold and clammy. His level of consciousness was decreased. He showed clinical anemia with pale palms and nails. Patient had a history of gallbladder pain for three years recently treated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy one week before. Patient had no history of peptic ulcers but a long history of NSAIDs use. We suspected some operative injury and emergency endoscopy was done. On endoscopy a large hematoma was found in first part of duodenum (Figure 1). Gastroenterology consult was taken immediately, and decision was made no to cauterize it as hematoma was too large and any intervention may result in more bleeding. Patient was treated conservatively initially. Later duodenectomy with end to end anastomosis was performed via open laparotomy. Patient is now recovering well and has resumed good state of health.

Discussion

Peptic ulcers are becoming more and more common with the increasing use of NSAIDs. Our patient was a chronic user of them, though he never complained of any ulcer related problems, this may be because his gall bladder pain might have masked the ulcer’s pain. Stress during the surgery also contributed towards ulceration though its pathogenesis is still not very clear. Excessive gastric acid production is probably not the principle factor leading to its development [4]. The loss of barrier protection is probably related to a marked reduction in perfusion of the gastric submucosa during critical illness. Splanchnic vasoconstriction represents an early response to a reduction in global oxygen delivery as blood is diverted to the vital organs such as the heart and brain. The reduction in splanchnic blood volume is disproportionately greater than that seen in other vascular beds [5]. Recognition of this phenomenon and more aggressive and timely resuscitation has probably led to the reduction in overall incidence of stress ulceration over the last twenty years [6].

In addition to this mechanism of stress ulceration, our patient, a chronic user of NSAIDs had increased risk of peptic ulcer perforation because NSAIDs are known to decrease gastric barrier protection. This damage is caused mainly through the ability of these agents to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis, which has a negative impact on several components of mucosal defense [7].

Our patient, who had to go through duodenectomy later, should have been assessed before any surgical procedure for such possible complications. Prophylactic measures could have been taken to reduce the risk of perforation. According to some studies, the earliest prophylactic regimens consisted of antacids administered via nasogastric tube and titrated to maintain an intra gastric pH > 3.5. Also, the introduction of Histamine -two (H2) antagonists greatly simplified stress ulcer prophylaxis. Omeprazole, a potent proton-pump inhibitor with demonstrated clinical efficacy in chronic acid-peptic disorders, has only recently been evaluated as an agent for stress ulcer prophylaxis [8].

Conclusions

Peptic ulcer disease is getting more and more common with increased use of pain medications specially NSAIDs. It can also be due to infection by Helicobacter pylori. This can lead to gastric as well as duodenal ulcer. Any patient undergoing a major operative procedure should be investigated beforehand for peptic ulcer disease, as surgical stress also contributes towards ulcers and may lead to perforation or bleeding of previously existing ones. Our patient got into similar situation after going Laparoscopic cholecystectomy when his previous duodenal ulcer started bleeding leading to hypotension and hypovolemic shock. We emphasize on investigation any case of pain with associated use of NSAIDs previously as this will help evaluate chances of gastric ulcers and prevent future complications, especially if operative measure is to be taken.

Acknowledgement

To my grandmother, Khursheed Yaqoob.

References

- Wadie I Najm (2011) Peptic Ulcer Disease. Primary Care: Clinics in Office Practice 38(3): 383-394.

- S Devaji Rao (2014) Clinical Manual of Surgery. (1st edn). Elsevier, India, pp. 962.

- Milosavljevic T, Kostić-Milosavljević M, Jovanović I, Krstić M (2011) Complications of Peptic Ulcer Disease. karger: Digestive Diseases 29: 491-493.

- Baghaie AA, Mojtahedzadeh M, Levine RL, Guntupalli KK, Antone Jr Opekun (1995) Comparison of the Effect of Intermittent Administration and Continuous Infusion of Famotidine on Gastric pH in Critically Ill Patients. Critical Care Medicine 23(4): 687-691.

- RW Bailey, GB Bulkley, SR Hamilton, JB Morris, GW Smith (1986) Pathogenesis of Nonocclusive Ischemic Colitis. Annals of Surgery 203(6): 590-599.

- Porter JM, Ivatury RR (1998) In Search of the Optimal End Points of Resuscitation in Trauma Patients. The Journal of trauma. 44(5): 908- 914.

- John L Wallace (2001) Pathogenesis of NSAID-induced gastroduodenal mucosal. Best Practice & Research Clinical Gastroenterology 15(5): 691-703.

- Balaban DH, Duckworth CW, Peura DA (1997) Nasogastric omeprazole: Effects on gastric pH in critically ill patients. The Am J Gastroenterol 92(1): 79-83.