Assessment of the Quality of Family Planning Counseling Interventionsin Female Solid Organ Transplant Patients

Taoreed Azeez1* and Tamunosaki Abo Briggs2

1Department of Medicine, University College Hospital, Nigeria

2Department of Obstetrics & Gynaecology, University College Hospital, Nigeria

Submission:October 01, 2020;Published:October 21, 2020

*Corresponding author:Taoreed Azeez, MBChB, MWACP, MSc., Endocrinology, Metabolism and Diabetes Unit, Department of Medicine, University College Hospital, Ibadan, Nigeria

How to cite this article:Taoreed A, Tamunosaki A B. Insight into the Pathophysiology of Polycystic Ovarian Syndrome: The Genes are not to Blame?. Glob J Reprod Med. 2020; 8(1): 5556729. DOI:10.19080/GJORM.2020.08.555731.

Abstract

Objective: To evaluate if women were educated on the potential risks of unplanned post-transplant pregnancy and if the chart had documentation of contraception use and family planning discussions in solid organ transplant (SOT) patients at a major tertiary referral academic transplant center.

Methods: This quality improvement study was a retrospective chart review of female patients at SOT center. An anonymous survey to identify potential knowledge gaps regarding post-transplant pregnancy risk was given to health care providers.

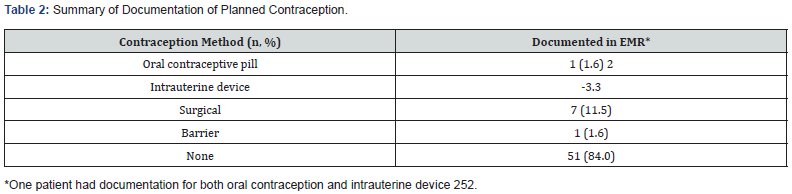

Result: A total of 62 out of 208 patient charts were screened and included in the study. Exclusions included male gender or not being of child-bearing potential. In the 62 charts, 1.6% had documentation for an oral contraception prescription, 1.6% received instruction to utilize barrier contraception, 3.3% received an intrauterine device (IUD), and 11.5% received surgical sterilization. There was no documentation of any method of contraception in 84% of the charts. There was documented counseling on the teratogenic effects of mycophenolate in 98% of the patient charts, however none had documented counseling on the maternal or fetal risk of pregnancy within two-years post-transplant. There was a 35% response rate to the healthcare provider survey with majority understood and counseled post-transplant regarding the importance of contraception.

Conclusion: This study demonstrated that there is an opportunity to address a lack of definitive family planning counseling, potentially by developing a multi-disciplinary approach. By utilizing all the resources and expertise of the multi-disciplinary team, this could improve the quality of patient education and reduce the risk of unplanned pregnancies in the female post-transplant population.

Keywords:Contraception; Transplant; pregnancy planning; Family planning; Fertility

Abbreviations:REMS: Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy; IUD: Intrauterine Devices; IRB: Investigational Review Board; EMR: Electronic Medical Record

Introduction

Women of reproductive potential account for over 35% of transplant recipients in the United States [1]. Prior to transplant, fertility is decreased due to primary organ-failure induced ovarian dysfunction, but posttransplant fertility quickly restores and ovulation may occur within one month [2]. Women should avoid pregnancy 12-24 months post-transplant due to increased risk of fetal and maternal complications [3]. Mothers are at increased risk of developing pre-eclampsia, graft loss, organ rejection, gestational diabetes, and spontaneous abortion while infants are at risk of prematurity, low birth weight, and fetal demise [2]. Additionally, there is an increased risk of birth defects with immunosuppressant medications, such as mycophenolate used in post-transplant patients [1]. Potential birth defects linked with mycophenolate in particular include structural abnormalities such as microtia or anotia, external auditory canal atresia, orofacial clefts, and colobomas [4,5]. Per the risk evaluation and mitigation strategy (REMS) program, healthcare professionals are responsible for counseling transplant patients on the importance of contraception and risks associated with unplanned post-transplant pregnancy while taking teratogenic drugs like mycophenolate. However, patients often do not recognize there is true risk because they have previously been infertile for years waiting for transplant and are unaware how quickly fertility returns within months of a successful transplant [6]. This results in up to 93% of pregnancies being unintentional or unplanned in the post-transplant population [7]. In addition, REMS counseling for these patients is mainly focused on the teratogenic effects of mycophenolate, rather than the spectrum of complications unrelated to drug exposure that can occur with pregnancy within the first two years post solid-organ transplant. Previously, data with high dose hormonal contraceptive use in this patient population suggested the potential for drug interactions associated with immunosuppressing drug use post-transplant, such as increased blood concentrations of corticosteroids and cyclosporine leading to toxicity [8,9]. While the topic of which contraceptives are safest to use in solid organ transplant patients is out of the scope of this paper, in general the use of low-dose hormonal contraceptives or intrauterine devices (IUD) are safe in the posttransplant patient population. Overall, there is a need to emphasize that it is important that female patients are adequately counseled on all available family planning options, so they can choose the best option for their lifestyle and family goals. The objective of this quality improvement study was to evaluate if women were educated on the potential risks of an unplanned pregnancy post-procedure in the pre-transplant stage. The study also determined if the patient charts had documentation of contraception, use, and family planning discussions in solid organ transplant (SOT) patients at a major tertiary referral academic transplant center.

Methods

This quality improvement study was reviewed and approved to proceed by both the University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Houston investigational review board (IRB) and the Memorial Hermann Healthcare System IRB. This was a single center, quality improvement study completed by a retrospective chart review. Data was collected from the electronic medical record (EMR) based upon the documented care that patients had already received and data was analyzed with descriptive statistics. Patients were identified from the patient transplant list at Memorial Hermann Transplant Center-Texas Medical Center. An anonymous survey was given to healthcare providers to evaluate knowledge on contraception interventions and potential risks of pregnancy in patients post-transplant. The survey was distributed electronically through email. A meeting occurred to give instructions on how to complete it, and once completed it was submitted anonymously via boxes provided in employee break rooms in respective clinic areas. For the retrospective chart review, inclusion criteria were female patients 11 years of age or older who received a solid organ transplant at Memorial Hermann Transplant Center-Texas Medical Center from January 2013 to July 2016. Patients were excluded if they were pregnant or not actively menstruating due to surgical or natural menopause. Solid organ transplant was defined as a transplanted organ including kidney, liver, and pancreas. Cardiac transplant patients were excluded since they were treated at a different transplant clinic. The clinical notes from all healthcare providers were reviewed, including physicians, social workers, and mid-level providers (nurse practitioners and clinical pharmacy specialists), to determine if potential family planning counseling had been discussed either pre- or post-transplant. Specifically, mentions of the maternal and fetal risks associated with pregnancy post-transplant were searched for. Additionally, the medication history was reviewed in the EMR for each patient to determine contraceptive use. For the survey, all members of the healthcare team employed at Memorial Hermann Transplant Center-Texas Medical Center were included. Healthcare professionals who did not practice in the transplant clinic or did not have direct contact with transplant patients were excluded from participating in the survey.

Result

A total of 208 charts of transplant patients were screened for inclusion from January 2013 to July 2016, with 62 charts meeting the inclusion criteria. Of the 146 charts that were excluded, 132 charts were for male patients and four charts were for patients that had a previous hysterectomy. The median age of patients in charts reviewed was 46 (11-65) years old and 67% of patients had a history of hypertension. Patient demographics are summarized in (Table 1). A thorough review of all clinical notes from all the respective healthcare providers and review of the medication histories found that 84% of the charts (51/64) had no documentation of contraception. The thirteen charts that had some form of contraception documented included the following: 1.6% received a prescription for oral contraception; 1.6% received instruction to utilize barrier contraception; 3.3% received an intrauterine device; and 11.5% received surgical sterilization. Mycophenolate was prescribed to 60 patients (97%). Of these patients, 56 (93%) had documentation of REMS counseling (Table 2). Eleven of 31 healthcare providers emailed responded to the survey (Table 3) for a response rate of 35%. Out of those who responded, the majority (81.8%) of healthcare providers were aware that fertility returns post-transplant. Regarding the timing of counseling, 60% of the respondents always counseled these women post-transplant whereas 22.2% always counseled pre-transplant. One healthcare provider reported two patients who experienced an unplanned pregnancy within one year of transplant. The survey results showed that there were multiple methods of acceptable contraception for the female transplant patients. For example, 64% of those responding to the survey recommended either barrier contraception or IUDs, and oral contraception was recommended by 56%. Surgical options were the least popular with only 18% of providers recommending this form of contraception.

Discussion

Pregnancy after solid organ transplant can lead to serious complications for the mother and fetus, the most concerning of these being loss of the organ and spontaneous abortion. This retrospective study observed that although most healthcare providers were aware of the risks of pregnancy post-transplant, there was no documentation of any discussions regarding pregnancy risks nor the need for family planning. Additionally, an overwhelming majority of patients had no documentation of contraception in place at the time of transplant. French and colleagues conducted a telephone survey regarding pre-transplant and post-transplant fertility awareness and contraception counseling in 309 women who received a solid organ transplant in a single institute [6]. This study observed that only 37% of women were counseled on the importance of contraception after transplant, and only 62% of women aged 15-44 years old were utilizing some form of contraception post-transplant.6 Of the patients who were counseled on contraception, 57% were recommended oral contraceptive pills and 20% were offered IUD. Another study noted condoms were utilized as contraception in 65% of female patient’s post-transplant, making it the most common form of contraception used in these patients. Condoms are not considered a highly effective contraception, with a failure rate of up to 24%. [1,7]. It was noticeable in the survey study by French and colleagues that there was limited documentation of contraception counseling. Based on the study results, French and colleagues raised the question regarding the extent providers discuss fertility and contraception in transplant patients and demonstrated that there is an unmet need in this subset of women with solid organ transplant [6]. The data observed in the retrospective chart review in this quality improvement study confirmed a similar troubling pattern as was reported in French and colleagues’ study [6]. The only documentation of counseling found in patient charts was related to the REMS program for patients who were prescribed mycophenolate. This contraception counseling is required per the REMS program and is specific to the drug. REMS counseling for these patients was mainly focused on the teratogenic effects of mycophenolate rather than the quick return of fertility and non-drug specific maternal and fetal risks within the first two years post solid-organ transplant. In this current study period, there was a report of one unplanned pregnancy in a transplant recipient from the survey results. As the study concluded, another transplant recipient was found to be pregnant ten weeks post-transplant. The frequency of unplanned pregnancies has not been monitored closely, but that was beyond the scope of the current study. The strengths of this study are that it was the first study conducted at this institution to determine compliance with contraception counseling in women post-transplant. The data demonstrates an opportunity to develop multidisciplinary collaborations to help facilitate family planning discussions, specifically the maternal and fetal risks associated with pregnancy within the first two years post solid organ transplant. The potential weaknesses of this study include the small patient population, the fact that it was retrospective in nature, and the relatively small response from the transplant healthcare team. Retrospective data collection relies upon the accuracy of documentation in the EMR when collecting data. The limited response from the healthcare team leads to the potential for self-selection bias. Data from the retrospective chart review was presented and discussed in a follow up meeting with the stakeholders that included: transplant physicians, gynecologists, clinical pharmacy specialists, the transplant team social worker, the transplant team case manager, research staff, and pharmacy residents. It was identified that the recommendation to use contraception was primarily being discussed by the clinical pharmacy specialist in the context of taking mycophenolate due to potential teratogenic effects. Unless referred to gynecologists for evaluation of ovarian mass or cysts, there was no formal referral in place to ensure a family planning counseling discussion occurred as part of the transplant clearance process. This has been identified as a potential opportunity for quality improvement to formalize a process to ensure there is a multidisciplinary team approach to family planning counseling. One such way could include engaging a gynecologist, maternal fetal medicine, and a fertility specialist to improve compliance with documentation of fertility counseling, family planning, and ensure a contraception plan is in place prior to transplant for all female patients of child bearing age. Another option being considered is standardizing the clinic note template to include fertility and family planning as a prompt to discuss with women of childbearing potential. The team recognized that it is possible many patients are unaware how quickly fertility can return posttransplant, and therefore may not appreciate or follow the recommendations for contraception while taking mycophenolate. Patient education materials are being reviewed to incorporate highlighting the need for family planning and recommending visiting with a gynecologist prior to transplant. In addition, the development of innovative educational interventions to optimize compliance with contraceptive use and prevent complications in this patient population is underway. In conclusion, this quality improvement study demonstrated that there is a lack of family planning counseling in female SOT patients. There is an opportunity to address this and reduce the risk of posttransplant pregnancy by different methods. One method would be the implementation of a multi-disciplinary approach. First, gynecologists and maternal fetal medicine specialists discuss fertility post-transplant, potential family planning options, and emphasize the risk of an unplanned pregnancy post-transplant on fetal development and viability. Afterwards, a clinical pharmacy specialist can then discuss required medication education and counseling for immunosuppressive medications, such as mycophenolate and its teratogenic risks. This would be followed by the transplant team reinforcing the risk of unplanned pregnancy and its risk for organ rejection. By utilizing all the resources and expertise of the multi-disciplinary team, this could improve the quality of patient education and reduce the risk of unplanned pregnancies in the female posttransplant population [10].

Author Contribution

AF, JAS – study concept, protocol, data analysis, final manuscript preparation; AF, AJ – data collection, NSC- data audit, final manuscript preparation, AB, EN – study concept, protocol, final manuscript preparations, JAS study oversight and monitoring.

References

- Rafie S, Lai S, Garcia J, Mody S (2014) Contraceptive use in female recipients of a solid-organ transplant. Prog Transplant 24(4): 344-348.

- Deshpande NA, Coscia LA, GomezLobo V, Moritz MJ, Armenti VT (2013) Pregnancy after solid organ transplantation: a guide for obstetric management. Rev ObstetGynecol 6(3-4):116-125.

- McKay DB, Josephson MA, Armenti VT (2005) Reproduction and transplantation: report on the AST Consensus Conference on Reproductive Issues and Transplantation. Am J Transplant 5(7):1592-1599.

- Hoeltzenbein M, Elefant E, Vial T (2012) Teratogenicity of mycophenolate confirmed in a prospective study of the European Network of Teratology Information Services. Am J Med Genet A 158(3):588-596.

- Anderka MT, Lin AE, Abuelo DN, Mitchell AA, Rasmussen SA (2009) Reviewing the evidence for mycophenolate mofetil as a new teratogen: case report and review of the literature. Am J Med Genet149(6):1241-1248.

- French V, Davis J, Sayles H, Wu S (2013) Contraception and fertility awareness among women with solid organ transplants. Obstetrics & Gynecology 122: 809-814.

- Guazzelli CA, Torloni MR, Sanches TF, Barbieri M, Pestana JO (2008) Contraceptive counseling and use among 197 female kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation 86(5):669-672.

- Deray G, le Hoang P, Cacoub P, Assogba U, Grippon P, et al. (1987) Oral contraceptive interaction with cyclosporin. Lancet 1(8525):158-159.

- Legler UF, Benet LZ (1986) Marked alterations in dose-dependent prednisolone kinetics in women taking oral contraceptives. Clin PharmacolTher 39(4):425-429.

- Secura GM, Allsworth JE, Madden T, Mullersman JL, Peipert JF (2010) The Contraceptive CHOICE Project: reducing barriers to long-acting reversible contraception. Am J of ObstetGynecol 203(2):115.