Latent Female Genital Tuberculosis Causes Tubal Defect Leading to Infertility

Siddhartha Chatterjee1*, Bishista Bagchi2, Arpan Chatterjee3 and Abira Datta4

1Director, Calcutta Fertility Mission, India

2 Clinical Associate, Calcutta Fertility Mission, India

3Specialist Consultant, ESI Hospital Kolkata, India

4Molecular Biologist and biochemist, Calcutta Fertility Mission, India

Submission: March 3, 2020; Published:March 09, 2020

*Corresponding author:Siddhartha Chatterjee, Calcutta Fertility Mission, 21 Bondel Road, Kolkata 700019, India

How to cite this article:Siddhartha C, Bishista B, Arpan C, Abira D. Latent Female Genital Tuberculosis Causes Tubal Defect Leading to Infertility. Glob J Reprod Med. 2020; 7(4): 5556718.DOI: 10.19080/GJORM.2019.07.555718.

Abstract

Latent genital tuberculosis (LGTB) is commonly asymptomatic, and it is usually diagnosed during infertility investigations. Despite of recent advances in imaging tools, such as computerized tomography (CT) scan, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and ultrasonography, hysterosalpingography (HSG) is still considered as the standard screening test for evaluation of tubal factor infertility and a valuable tool for diagnosis of latent female genital tuberculosis. Various appearances on HSG from non-specific changes to specific findings have been detected in women with female genital tuberculosis (FGTB). The main objective of the present study was to establish the role of LGTB in causing minor tubal defects leading to tubal factor infertility in 423 infertile women from January 2016- December 2018 at our institute. These patients had undergone DNA-PCR test (polymerase chain reaction) for screening of LGTB, HSG in between Day 6 – Day 12 of cycle and then had had subsequent treatment with anti-tubercular drugs (ATD) with or without laparoscopy. The Clinical pregnancy rate, miscarriage rate and live birth rate after treatment were analyzed and were found to be statistically significant when compared among groups of women who were treated with ATD; treated with ATD and laparoscopy and those who were treated with laparoscopy alone (PCR negative) .

Keywords: Latent genital tuberculosis; Tubal defect; Infertility; Laparoscopy; Pregnancy

Abbreviations: LGTB: Latent Genital Tuberculosis; MRI: Magnetic Resonance Imaging; CT: Computerized Tomography; HSG: Hysterosalpingography; ATD: Anti-Tubercular Drugs; ATT: Anti-Tubercular Treatment

Introduction

LGTB is a major health problem in many developing countries in Asia and Africa and has been proved to be responsible for a significant proportion of female infertility. The detection of LGTB often goes unnoticed as it is asymptomatic in majority of the affected women and is diagnosed only during infertility work-up [1]. The silent invader of the genital tract tends to create diagnostic dilemmas and diverse findings on imaging and endoscopy. The most involved genital organs (whether solely or with other organs) have been seen to be fallopian tubes (63.84%), ovaries (46.15%), endometrium (38.46%) and the cervix (23.07%) in female genital tuberculosis but the involvement has not been documented in LGTB [2]. However, a few reports have found the endometrium to be involved the most with as high as 69% in cases of secondary infertility [3] Hysterosalpingography (HSG) is a useful tool in visualizing the abnormalities in the fallopian tubes. Tubal images vary from non-specific changes such as tubal dilatation, tubal occlusion, irregular contour, hydrosalpinx to tubal occlusion, obstruction in the transition zone between the isthmus and ampulla, multiple constrictions, presence of synechiae and adhesions in the peri tubal region [4,5]. The minimum Mycobacterium concentration required for detection of tubercular bacilli in a certain sample is quite high when subjected to histopathology (10,000bacilli/ml) or different culture media like LJ (1000bacilli/ml) or BACTEC (10-100bacilli/ml) whereas DNA-PCR technique can detect even 10bacilli/ml. In our study we have used DNA-PCR (polymerase chain reaction) technique with high sensitivity of 96.4 % and specificity of 100 %, as any specific test for detection of LGTB has not yet been documented [6] Therefore, the present study was conducted to determine the role of latent genital tuberculosis in structural and functional changes of the fallopian tube , diagnosed by HSG features and on laparoscopy and its post-treatment outcomes.

Material and Methods

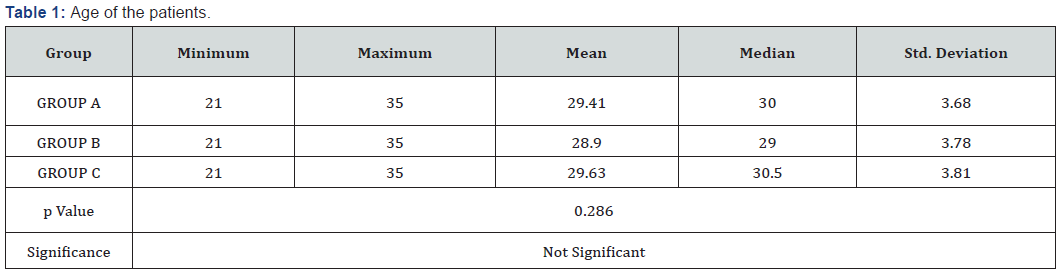

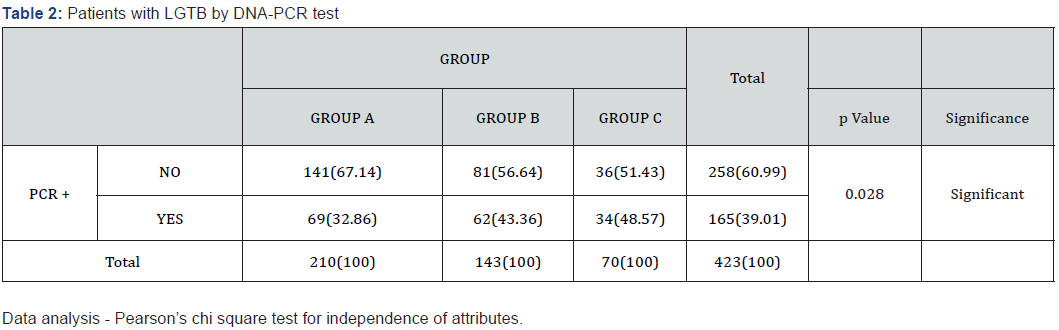

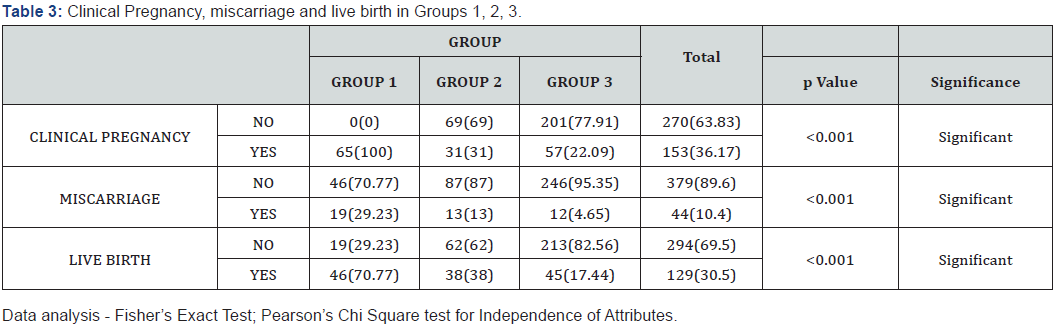

This retrospective study was conducted at Calcutta Fertility Mission in Kolkata, India, from January 2016 to December 2018. The data were collected from a total of 423 patients as cases between 20-35years of age, who had primary infertility due to tubal defects detected by HSG or laparoscopy. They did not have any history of cigarette smoking or alcoholism. Patients were grouped into Group A (210), Group B (143) and Group C (70) depending on the features of the fallopian tube on HSG or laparoscopy associated with latent genital tuberculosis. They had undergone routine tests along with the DNA-PCR test with an endometrial aspirate on day 21 to day 24 of respective menstrual cycles, HSG from Day6 – Day 12 of the cycle and laparoscopy as required. 65 patients had conceived within one year of the treatment with ATD, either spontaneously or by ovulation induction. The remaining patients had undergone laparoscopy for diagnosis and correction of minor tubal defects. These patients were further classified into Groups 1, 2 and 3 based on their post-treatment outcome. 65 women who had conceived after administration of only ATD were in Group 1; 100 women with LGTB who had no pregnancy after anti-tubercular treatment (ATT) and required laparoscopy were grouped as Group 2. 258 PCR negative patients who were subjected to laparoscopy were in Group 3. The Clinical Pregnancy Rate, miscarriage rate and live birth rate were calculated.

Statistical Analysis

Categorical variables are expressed as Number of patients and percentage of patients and compared across the groups using Pearson’s Chi Square test for Independence of Attributes/ Fisher’s Exact Test as appropriate. Continuous variables are expressed as Minimum, Maximum, Mean, Median and Standard Deviation and compared across the groups using Kruskal Wallis Test. The statistical software SPSS version 20 has been used for the analysis. An alpha level of 5% has been taken, i.e. if any p value is less than 0.05 it has been considered as significant.

Ethical Consideration

The Ethical Committee of Calcutta Fertility Mission has given clearance for the retrospective study of a prospective database on 12/10/2019 (CFM/2019/028). Written informed consent has been obtained from all women who participated in the study.

Result

Out of 423 patients, 66 women in Group A (210) had isthmian or ampulla blockage, 30 of them had cornual block and 114 had block in the fimbria end (unilateral or bilateral). 143 patients in Group B had coiled, kinked or beaded tubes (unilateral or bilateral). In Group C, 70 patients had features of extravasation in the wall of the fallopian tube or cornual extravasation. 165 patients were found to be DNA-PCR positive i.e. affected with LGTB and 258 women had negative results. These women were treated with a course of anti-tubercular drugs (ATD) for 6 completed months and the post-treatment outcome was documented Table 1-3.

Discussion

Latent genital tuberculosis is a rare disease in developed countries but is an important cause of subclinical chronic pelvic inflammatory disease and infertility in underdeveloped and developing countries. Previous literature show LGTB as a cause of infertility in 1–18% of women, varying from 1% in the developed countries and 18 % in India [7,8].The fallopian tubes are the most common affected pelvic organs, followed by endometrium, ovary and cervix in female genital tuberculosis but the involvement may differ in LGTB [9-11]. In developing countries, it is not cost effective to perform laparoscopy for all infertile women and HSG continues to be the preliminary investigation to detect the abnormalities of the uterus and fallopian tubes and their patency [12]. During the past two decades, the clinicians have faced quite a number of cases of LGTB and its consequences such as infertility, so reviewing of these features are considered in differential diagnosis of the causes of infertility and consequent intervention and treatment. Multiple HSG findings for diagnosis of tubercular infestation has been given by various authors such as tubal obstruction between the isthmus and the ampullary portion of the fallopian tube, an everted or agglutinated fimbria with a patent orifice , slight or moderate dilatation of the ampullary portion of the fallopian tube. Small synechiae of the uterine cavity in the absence of clinical history of curettage or pelvic surgery may be due to LGTB. [13-16] In our study 15.6% of the patients were seen to have block in the isthmus or ampulla; 7.09% of the enrolled patients had cornual block and 26.9 % of them had fimbria block. 33.8% of the women had tubal kinking, convoluted or beaded tubes and 16.5% patients had tubal or cornual extravasation. In our study the following minor tubal defects were more common on laparoscopy:

a. Tubal kinks due to serosa-serosal adhesions

b. Shortening of the tubal length

c. Distorted position of the tube due to shortening of infundibula pelvic ligament

d. Hydrosalpinx is less common

Tubal block due to mucosal edema or adhesion inside the fallopian tube can also be seen in LGTB. All these tubal defects can be corrected by laparoscopy in genital tract is free of tubercular bacilli infestation. The Clinical pregnancy rate was about 22% in this study which correlates with the previous literature on pregnancy rate in minor tubal defects (27%) [17] .These features of the fallopian tubes detected as per HSG or laparoscopy also correlate with the present study that there is a significant pelvic morbidity and tubal damage due to genital tuberculosis. Multidrug ATT is the mainstay of management and laparoscopy may be required in advanced cases of tubal defects. Conception rates are low among infertile women with LGTB even after multidrug therapy and the risk of complications such as ectopic pregnancy and miscarriage has been shown to be high by Grace GA et al. [18] In our study 39.3% patients had conceived within 1 year of treatment with ATD and the rest of them had undergone laparoscopy for tubal defect correction. In Groups 1, 2 and 3, 36.17% of the women conceived after respective treatment of which 10.4% had miscarriage and about 30% had live birth in our study. The Clinical pregnancy rate, live birth rate and miscarriage rate in Groups 1, 2, 3 were found to be statistically significant. (p value < 0.001). According to Tsiami et al. [19] proximal tubal occlusion, tubal aspiration and salpingectomy for treatment of hydrosalpinx were superior to no intervention for an outcome of clinical pregnancy. No superiority could be found among the three surgical methods for any of the outcomes. In terms of relative ranking, tubal occlusion was the best surgical treatment followed by salpingectomy for ongoing and clinical pregnancy rates [19]. In previous literature mild tubal abnormality (class I) had a 34% cumulative pregnancy rate, patients with moderate salpinx abnormality (class II) had a 16% cumulative pregnancy rate, and those with severe salpinx abnormality (class III) had a 10% cumulative pregnancy rate. No intrauterine pregnancies were observed in the most severe group (class IV). Hence it has been concluded by Xiu JX et al. [20] that surgical laparoscopy is helpful for class I and II tubal abnormality, while it is not for class III and IV abnormalities [20]. In our study 31% of the patients conceived after treatment with ATD and laparoscopy and 22.09% of the women who were PCR negative had conceived after laparoscopy alone. According to Filippini F et al. [21] laparoscopic surgery should be the first-line treatment of distal tubal occlusion in stage I and II. In stage IV, in-vitro fertilization (ART-IVF) should be suggested immediately. In stage III, the choice of treatment is more difficult: the main prognostic factor might be the tubal mucosal appearance [21]. Laparoscopic surgical corrections for minor tubal defects yield comparable clinical pregnancy rates to ART (25-30%), but for major tubal defects (5.7%) and severe endometriosis (18.5%), the latter is superior to the former [22]. The rate of miscarriage in an ongoing pregnancy was high in women with LGTB, the CPR per cycle was low and spontaneous abortion was high [22]. Similar findings has been documented in our study in which miscarriage rates are 29.23% in Group 1 and 13% in Group 2; whereas it is only 10.4% in PCR negative Group 3 and it is statistically significant. (p value < 0.001)

Conclusion

The tubercular infestation or latent FGTB as per our study appears to be a very important cause of minor tubal defects in patients with tubal factor infertility. It should be detected and treated adequately either with ATT or both with ATT and laparoscopy for promising reproductive outcome.

Table 2:

Data analysis - Fisher’s Exact Test; Pearson’s Chi Square test for Independence of Attributes. Table 3: Clinical Pregnancy, miscarriage and live birth in Groups 1, 2, 3.

References

- Rom W, Garay S (1996) Tuberculosis, (1st), Little Brown, New York, USA.

- Boubacar Efared, Ibrahim S Sidibé, Fatimazahra Erregad, Nawal Hammas, Laila Chbani, et al. (2019) Female genital tuberculosis: a clinicopathological report of 13 cases. Journal of Surgical Case Reports (3): 083.

- Ojo BA, Akanbi AA, Odimayo MS, Jimoh AK (2008) Endometrial tuberculosis in the Nigerian middle belt: an eight-year review. Trop Doct 38(1): 3-4.

- Ahmadi F, Zafarani F, Shahrzad G (2014) Hysterosalpingography appearances of female genital tract tuberculosis: Part I. Fallopian tube. Int J Fertil Steril 7(4): 245-252

- Khalaf Y (2003) ABC of subfertility. Tubal subfertility. BMJ 327(7415): 610-613.

- Bhanu NV, Singh UB, Chakraborty M (2005) Improved diagnostic value of PCR in the diagnosis of female genital tuberculosis leading to infertility. J Med Microbiol 54(10): 927-931.

- Schaefer G (1976) Female genital tuberculosis. Clin Obstet Gynecol 19: 223.

- Muir DG, Belsey MA (1980) Pelvic inflammatory disease and its consequences in the developing world. Am J Obstet Gynecol 138(2): 913-928.

- Chavhan GB, Hira P, Rathod K, Zacharia TT, Chawla A (2004) Female genital tuberculosis: hysterosalpingography appearances. Br J Radiol 77: 164-169.

- Sharma JB, Pushparaj M, Roy KK, Neyaz Z, Gupta N, et al. (2008) Hysterosalpingography findings in infertile women with genital tuberculosis. Int J Gynecol Obstet 101(2): 150-155.

- Ahmadi F, Zaferany M, Shahrzad G (2014) Hysterosalpingography appearance of genital tuberculosis: par t11. Int J Ferti Steril 8: 13-20.

- Sharma JB, Roy KK, Pushparaj M, Gupta N, Jain SK, et al. (2008) Genital tuberculosis: an important cause of Ashermans syndrome in India. Arch Gynecol Obstet 277(1): 37-41.

- Jindal UN (2006) An algorithmic approach to female genital tuberculosis causing infertility. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis 10(9): 1045-1050.

- Eng CW, Tang PH, Ong CL (2007) Hysterosalpingography. Current applications. Singapore Med J 48(4): 368-373.

- Gupta N, Sharma JB, Mittal S, Singh N, Misra R, et al. (2007) Genital tuberculosis in Indian infertility patients. Int J Gynecol Obstet 97(2): 135-138.

- Chatterjee S (2010) Minor tubal defects- The unnoticed causes of unexplained infertility. J Obstet Gynecol India 60: 331-336.

- Grace GA, Devaleenal DB, Natrajan M (2017) Genital tuberculosis in females. Indian J Med Res. 145(4): 425-436.

- Tsiami (2016) Surgical treatment for hydrosalpinx prior to in-vitro fertilization embryo transfer: a network meta-analysis. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol 48(4): 434-445.

- Xiu JX, Bin LY, Jin WR, Min ZY, Jun L, et al. (2015) Preliminary results of tubal surgery with pregnancy outcome. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol 42(4): 505-509.

- Filippini F, Darai E, Benifla JL, Renolleau C, Sebban E, et al. (1996) Distal tubal surgery: a critical review of 104 laparoscopic distal tuboplasties. J Gynecol Obstet Biol Reprod 25(5): 471-478.

- Chatterjee S, Chatterjee A, Chowdhury RG, Dey S, Ganguly D (2012) Fertility Promoting Laparoscopic Surgery: Our Experience. J South Asian Feder Obst Gynae 4(1).

- Bagchi B, Chatterjee S, Gon Chowdhury R (2019) Role of latent female genital tuberculosis in recurrent early pregnancy loss: A retrospective analysis. Int J Reprod Bio Med 17(12): 929-934.