Endometriosis and Microbiota: Is there a Relationship with the Perinatal Period?

M Bardi1*, F Arioli2 and N Rovelli3

1 Senior Consultant, Italy

2 Midwife, freelancer, Italy

3Midwife Lecturer, University Milano Bicocca, Italy

Submission: December 17, 2019; Published:January 09, 2020

*Corresponding author:M Bardi, Senior Consultant and Referent of the Multidisciplinary Team for Endometriosis care at the Policlinic San Pietro (San Donato Group) in Ponte San Pietro, Italy

How to cite this article:M Bardi, F Arioli, N Rovelli. Endometriosis and Microbiota: Is there a Relationship with the Perinatal Period?. Glob J Reprod Med. 2020; 7(2): 5556713. DOI: 10.19080/GJORM.2019.07.555713.

Abstract

The gut microbiota is a complex community of bacteria residing in the intestine. Animal models have demonstrated that several factors contribute to and can significantly alter the composition of the gut microbiota, including genetics; the mode of delivery at birth; the method of infant feeding; the use of medications, especially antibiotics; and the diet. The intestinal microflora provides a strong defense against intestinal pathogens and may be altered in inflammatory conditions that impact the gut, such as endometriosis. This research is in the form of a quantitative study aimed at discovering the relationship with development of the intestinal microbiome in the perinatal period and the impact of these microbiota on the local endometrial microenvironment as these mechanisms may influence gynecologic health outcomes and onset of endometriosis. We hypothesized that disease-specific changes of gut microbiota in patients with endometriosis may a provide new insights for psychological intervention, to improving the prognosis of endometriosis patients.

Keywords: Gut microbiota; Endometriosis; Pregnancy; Neonatal period

Introduction

Endometriosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity, predominantly, but not exclusively, in the pelvic compartment. It is an oestrogen -dependent chronic inflammatory con¬dition that affects women in their reproductive period and is associated with pelvic pain and infertility [1]. The prevalence of endometriotic disease seems to be ~5%, with a peak between 25 years and 35 years of age [2]. The disease seems frequent in adolescent women with chronic pelvic pain [3]. The pathogenic hypothesis supported by the most robust evidence is based on the so-called retrograde menstruation phenomenon. Viable endometrial fragments are driven through the fallopian tubes, possibly by a pressure gradient originating from dys-synergic uterine contractions. Once they reach the peritoneal cavity, they can implant, grow and invade onto pelvic structures. The likelihood of this event is influenced epidemiologically by any menstrual, reproductive or personal factor that would augment pelvic contamina¬tion by regurgitated endometrium such as early age at menarche or a long duration of menstrual flows, and biologically by any alteration at the molecular level that favors the stepwise process of cell implantation and growth at ectopic locations [4].

Microbiota

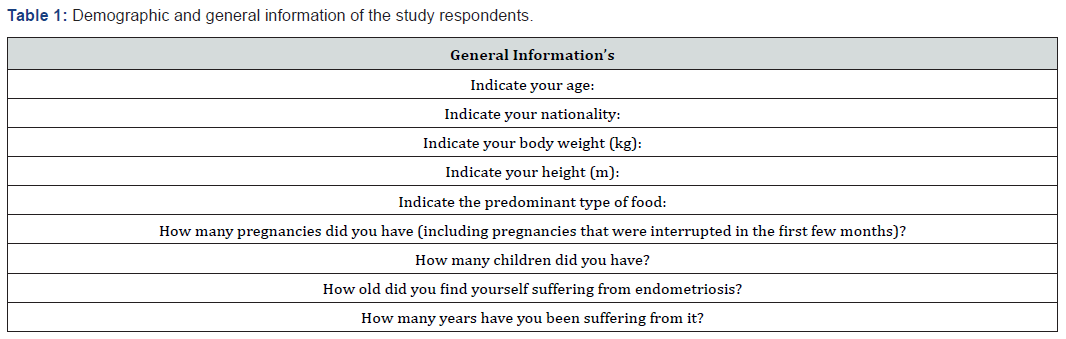

The term microbiota indicates the set of microorganisms that live and colonize a specific environment at a specific time [5]. In particular, the human microbiota is an organism composed of bacteria, archaea and microbial eukaryotes, such as protozoa, fungus and nematodes. It is estimated that there are approximately 10,000 billion microorganisms belonging to the human microbiota against 1000 billion human cells. According to some researchers, these microorganisms have such an influence on human physiology that they should be considered part of its genome [6]. The 10,000 billion microorganisms that live in and on the body perform different functions: protective, structural and metabolic. To confirm this hypothesis, the intestinal and vaginal microbiome have been variously studied also with the new molecular techniques. The latter mainly concerns the gene sequencing for the 16S subunit of ribosomal RNA, or rRNA, or a specific gene of all bacteria. The metabolic capacities of the bacteria have been deciphered sequencing all the genes of a microbial community (Table 1). The studies object was mainly the vaginal microbiome and the influence of its alterations in health and gynecological pathology. As early as 2002, Dr. David Barker introduced the concept of “fetal origins of adult disease”, arguing that the intrauterine environment in which the fetus develops can influence postnatal conditions. The microbiome is therefore a mechanistic mediator in the origins of the development of health and disease [7].

Microbiota and Maternal-Fetal Relationships

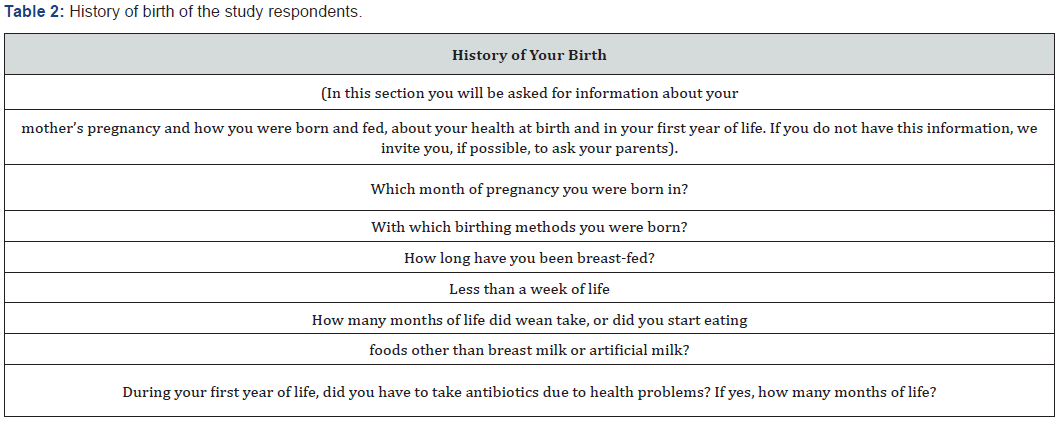

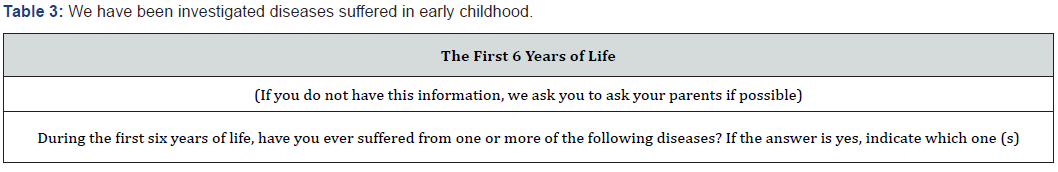

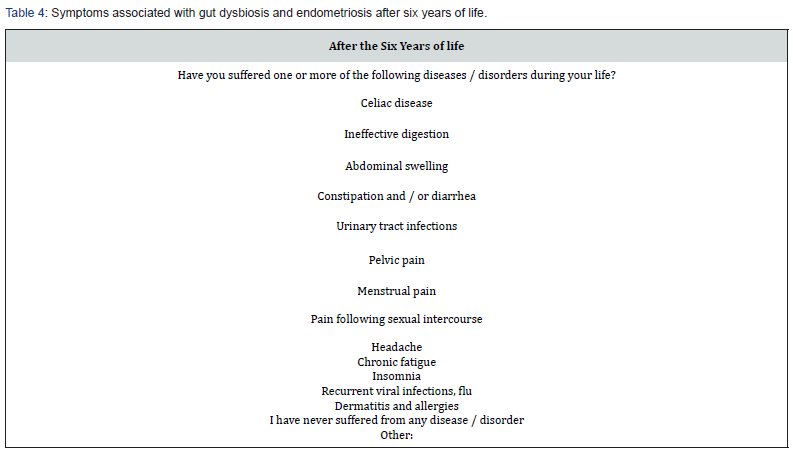

Until recently, the intrauterine environment was considered sterile, as were the fallopian tubes and the anatomical appendages of pregnancy (placenta and amniotic fluid). The theory that the first colonization of the gastrointestinal tract of the new-born occurs at the time of the first breastfeed is also widespread in the literature. However, several studies of the human microbiome over the last few years, through the molecular-based technique of rRNA 165 gene sequencing, indicate that this fetal colonization begins already in utero [8]. Non-pathogenic bacteria have also been found in amniotic fluid and placentas of healthy newborns, suggesting an exchange of microbes between mother and fetus [9]. Recently RW Walker [10] sampled 15 mother-child twosomes: meconium contained bacteria detected in the placenta and amniotic fluid, despite the unique composition and function of meconium and found that bacterial transmission increased during pregnancy. These results indicate that the maternal microbiome carry out a fundamental role in shaping the fetal intestinal microbiome, taking part in a vertical transfer. Recent studies have characterized how host genetics, prenatal environment and delivery mode can shape the new-born microbiome at birth. Following this, post-natal factors, such as antibiotic treatment, dieting, and exposure to a variety of microbial organisms during early life has been hypothesized to a protective effect in the newborn. Furthermore, epidemiological studies have shown that there are other diseases in infants during childhood increase the risk for several diseases, highlighting the importance of understanding early life microbiome composition [11]. Maternal vaginal infections or periodontitis can result in bacteria invading the uterine environment (Table 2-4). Gut and oral microbiota could be transported through the bloodstream from the mother to the fetus. Delivery mode shapes the initial bacterial inoculum of the new-born. Postnatal factors such as antibiotic use, diet (such as breast-feeding versus formula, and introduction of solid food), genetics of the infant and environmental exposure further configure the microbiome during early life [11].

Microbiota, Dysbiosis and Inflammation

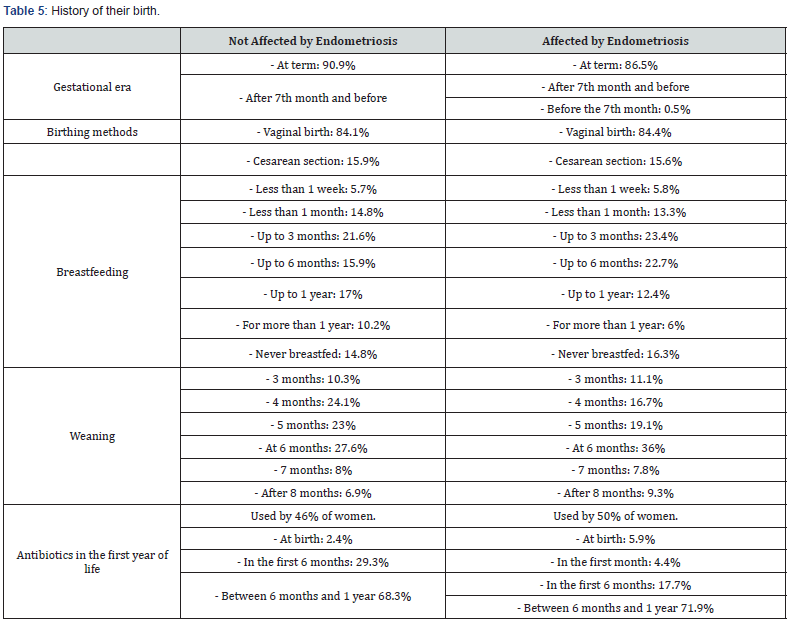

Dysbiosis is an alteration of the balance and composition of the microbiota and microbiome that colonizes a specific anatomical site. Intestinal dysbiosis, for example, involves a set of signs, symptoms and disorders of the gastrointestinal tract, which can also have consequences on organs and systems distant from the intestine [12]. An important consequence of the alteration of the microbial community is the modification of the functional gene part present in the intestinal microbiome. Dysbiosis negatively influences homeostasis through reduced microbial diversity and increased inflammatory reaction. A reduction in cell-cell junctions occurs at the level of the intestinal epithelium, which leads to an increase in permeability and subsequently to bacterial translocation. The latter can lead to an inflammatory state with the consequent exacerbation or induction of the disease [13]. Among these numerous discoveries, the various studies on the influence of human (especially intestinal) microbiome on oestrogen -dependent diseases play a fundamental role. It is well known, for example, that the high levels of adipose tissue are associated with increased production of oestrogen, which is considered a key factor in female reproductive tumours and therefore in hyperplasia. Many tissues express oestrogen receptors, including intestines, brain, bones and adipose tissue (Table 5 & 6). Oestrogen plays a significant role in numerous gynaecological conditions with different mechanisms, such as increasing the epithelial barrier, glycogen levels, mucus secretion and indirectly decreasing vaginal pH by promoting the abundance of Lactobacilli and acid production lactic acid [13].

Oestroboloma

Along with the new knowledge on the microbiome, in recent years scientific discoveries concerning oestroboloma are also spreading. This term means “a complex interaction between oestrogen, intestinal microbiome and sites of the distal mucosa”; it is defined as “gene repertoire of the gut microbiota that is able to metabolize oestrogen “ [13]. In fact, not only the oestrogens can modify the intestinal microbiome, but the latter can also significantly influence the levels of oestrogen: they are metabolized by the enzyme beta-glucuronidase, secreted by the microbes, in the passage from their forms conjugated to their forms deconjugate; the oestrogens are thus made free and available to bind to their receptors, influencing the physiological oestrogen -dependent processes. Oestroboloma can regulate homeostasis at sites of intestinal and distal mucosa (Table 7). When dysbiosis occurs, the action of beta-glucuronidase is altered, causing hyperactivation and / or a deficiency of the estrogenic value and thus contributing to oestrogen -related pathological states [13].

Microbiota and Endometriosis

Recent studies present strong evidence for an association between dysbiosis, i.e. disruption of the gut microbiota, and inflammatory bowel disease, neuropsychiatric diseases, psoriasis, arthritis, and some cancers, especially colon cancer [12]. This is explained by the potential immunoregulatory function of the gut microbiota playing a role in systemic inflammatory cellular responses. Since abnormal inflammatory response and activation of immune cells in the peritoneal cavity are thought to play a role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis, an association between microbiota and endometriosis is likely [14]. Therefore, the current mechanistic studies on endometriosis are insufficient. Patients with endometriosis are at high risk of various chronic diseases, such as autoimmune diseases, cancer, asthma / atopic diseases, cardiovascular and inflammatory bowel diseases [15]. Endometriosis shares similar characteristics, such as decreased apoptosis, elevated cytokine levels and cellmediated abnormalities, with several autoimmune diseases, thus endometriosis holds a strong relationship with complex immune disorders [16]. Prior research has shown that dysbiosis leads to increased oestrogen levels in the circulation [17]. Increased oestrogen exposure can stimulate growth of ectopic endometriotic foci and inflammatory activity in them. Even the intestinal microbiota has been shown to be an important regulator of these inflammatory processes: macrophages, neutrophils and mast cells can be influenced by intestinal microbial variations and by its greater epithelial permeability [14]. Furthermore, the activation of IL-17-secreting CD4 T lymphocytes derives from this inflammatory reaction, a proinflammatory cytokine that appears to play a fundamental role in the pathogenesis of endometriosis by hypervascularization of the peritoneal surface, with consequent implantation and proliferation of endometrial tissue ectopic. The concentration of IL-17 was significantly superior in the peritoneal fluid of women with endometriosis. Furthermore, the composition of the intestinal microbiota is correlated with the homeostasis of stem cells and progenitor in the bone marrow and an involvement of these cells in the development of endometriosis has been demonstrated [14]. It is plausible that microbiota can play a role in the development of endometriosis by affecting the host’s epigenetic, immunologic and / or biochemical functions [18].

Materials and Method

Voluntary completion of an anonymous survey was promoted (online and paper sampling). The survey was designed on the basis of information from literature review on multiple interactions between endometriosis and microbiota, and on the hypothesis that an alteration of the fetal and neonatal microbiota could, in some way, interfere with the onset of endometriosis. We sent a questionnaire to 100 women suffering from endometriosis and 100 healthy women (which we call “controls”). The 200 women were asked to report the course of the 3rd trimester of the pregnancy from which they were born (naturally asking for news to their mother), the methods of birth and the first 6 months of their life. We then asked to report on any pathologies that arose in the following years.

Consent to the Treatment of Sensitive Data

After having read and having understood the information above, concerning the study: “Health and gynecological pathology in relation to the human microbiome: development of new perspectives of Obstetric assistance for the promotion of women’s health” agrees does not consent to the processing of personal and sensitive data collected in the context of this study, access, consultation and any subsequent processing of the data collected from the components research group bodies and other authorized researchers. The processing of the data collected as part of the experimentation as well as their communication to other third parties and / or publication for scientific purposes are permitted but can only take place after the data has been made anonymous, under the responsibility and under the responsibility direct experimenter. The data collected will also be processed in accordance with the privacy regulations (GDPR, General Data Protection Regulation - EU Regulation 2016/679) and will always be represented in aggregate form. The results of the research were found from the responses of 88 women not affected by endometriosis and 81 women who are affected. The criteria are represented by the fertility and the absence of the state of pregnancy in all participating women.

a) To answer the questionnaire addressed to women not affected by endometriosis, note the relevance of women between 20 and 24 years with a percentage of 28.4%, against 17% of women over the age of 40. In 97.7% are women of Italian nationality. Body weight varies between 41 kg and 95 kg, while height varies between 1.50 m and 1.80 m, with a peak at 1.60 / 1.65 m. 97.7% report an omnivorous diet. 46.6% had no pregnancy in their lives, while 29.5% reported one, 9.1% of them reported three, 8% reported two, 6.8% reported more than three. Furthermore, 47.7% have no children, 29.5% have one, 17% have two, 5.7% have three.

b) To answer the questionnaire addressed to women suffering from endometriosis, note the relevance of women with over 40 years, with a percentage of 31.1%, followed by 30.2% of women between 35 and 39 years, 21.3% between 30 and 34 years up to 3.8% of women between 20-24 years. In 96.4% they are women of Italian nationality. Body weight varies between 40 kg and 130 kg, while the height varies between 1.50 m and 1.82 m. 93.9% report a diet omnivorous. 60.6% had no pregnancy in their lives, while 19.3% reported one, 14.3% of them reported two. Furthermore, 67.6% have no children, 18.5% have one, 12% have had children. These women found that they had endometriosis between 1 and 50 years. 45.3% are affected by more than 10 years, 21% for more than 5 years, 2.8% for 5 years, 2.8% for 3 years, 5.6% for 2 years.

Conclusion

The answers received show that there were no differences between the two groups as regards the course of the third trimester of intra-uterine life, the methods of birth, breastfeeding and any therapies performed in the first 6 months of life. What is certain is that some modification of the microbiota has taken place, since in the following years of life the women who then had endometriosis presented several pathologies in a much greater percentage than the controls. Pathologies, moreover, closely related to alterations of the intestinal microbiota. We believe that our survey is a starting point for further, more extensive and indepth research to correlate the alterations of the microbiota that occur at particularly early ages in a woman’s life and that can intervene in the genesis or predisposition to endometriosis.

References

- Giudice LC Clinical practice (2010) Endometriosis. N Engl J Med 362: 2389-2398.

- Parazzini F, Vercellini P, Pelucchi C (2012) In: Endometriosis science and practice. Giudice LC, Johannes LH, Healy DL, (Eds.), pp. 19-26.

- Janssen EB, Rijkers ACM, Hoppen brouwers K, Meuleman C, D Hooghe TM (2013) Prevalence of endometriosis diagnosed by laparoscopy in adolescents with dysmenorrhea or chronic pelvic pain: a systematic review. Hum Reprod Update 19(5): 570-582.

- Burney RO, Giudice LC (2012) Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis. Fertil Steril 98(3): 511-519.

- Piccini F (2003) Alla scoperta del microbioma umano: Flora batterica, nutrizione e malattie del progresso. Fabio Piccini. Edizione del Kindle.

- Andreas Schwiertz (2016) Microbiota of the Human Body: Implications in Health and Disease. cap 4: 6-7.

- DJP Barker, JG Eriksson, T Forsén, C Osmond (2002) Fetal origins of adult disease: strength of effects and biological basis. Int J Epidemiol 31(6): 1235-1239.

- Mc Elroy K, Regan M, Chung S (2017) Health and the Human Microbiome: A Primer for Nurses. Am J Nurs 117(7): 24-42.

- Stiemsma LT, Michels KB (2018) The Role of the Microbiome in the Developmental Origins of Health and Disease. Pediatrics 141(4): 243.

- Walker RW (2017) The prenatal gut microbiome: are we colonized with bacteria in utero. Pediatric Obesity 12(1): 3-17.

- Tamburini S, Shen N, Wu HC JC (2016) The microbiome in early life: implications for health outcomes. Nat Med 22(7): 713-722.

- Weiss GA, Hennet T (2017) Mechanisms and consequences of intestinal dysbiosis. Cell Mol Life Sci 74 (16): 2959-2977.

- Baker J, Al Nakkash L, Herbst Kralovetz M (2017) Review: Estrogen–gut microbiome axis: Physiological and clinical implications. Maturitas 103: 45-53.

- Laschke MW, Menger MD (2016) The gut microbiota: a puppet master in the pathogenesis of endometriosis. Am J Obstet Gynecol 215(68): e61-68.

- Kvaskoff M, Mu F, Terry KL, Harris HR, Poole EM (2015) Endometriosis: a high-risk population for major chronic diseases? Hum Reprod Update 21(4): 500-516.

- Beste MT, Pfaffle Doyle N, Prentice EA, Morris SN, Lauffen burger DA, et al. (2014) acson KB, Griffith LG. Molecular network analysis of endometriosis reveals a role for c-Jun-regulated macrophage activation. Sci Transl Med 6(222): 222ra216.

- Flores R (2012) Fecal microbial determinants of fecal and systemic estrogens and estrogen metabolites: a cross-sectional study. J Transl Med 10: 253.

- Ming Yuan, Dong Li, Zhe Zhang, Huihui Sun, Min An, et al. (2018) Endometriosis induces gut microbiota alterations in mice. Hum Reprod 33(46): 607-616.