Delays in Utilization of Institutional Delivery Service and its Determinants in Yem Special Woreda, Southwest Ethiopia: Health Institution Based Cross-Sectional Study

Teklemariam Ergat Yarinbab* and Sileshi Gebremichael Balcha

Department of Public Health, Mizan-Tepi University, Ethiopia

Submission: June 05, 2018;Published: July 17, 2018

*Corresponding author: Teklemariam ErgatYarinbab, Department of Public Health, Mizan-Tepi University, Ethiopia; teklemariam36@gmail.com;teklemariam@mtu.et

How to cite this article: Teklemariam E, SileshiGebremichaelBalcha. Delays in Utilization of Institutional Delivery Service and its Determinants in Yem Special Woreda, Southwest Ethiopia: Health Institution Based Cross-Sectional Study. Glob J Reprod Med. 2018; 5(3): 555661. DOI:10.19080/GJORM.2018.05.555661.

Abstract

Background: Pregnancy and childbirth remain serious life threateningevents for women in low income countries. Reducing maternal morbidity and mortality is a global priority health problem. One of the key strategies for reducing maternal morbidity and mortality is increasing institutional delivery service utilization of pregnant women under the care of skilled birth attendants. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the delays in utilizing institutional delivery service and its determinants among women who gave birth at public health institutions in Yem Special Woreda, Southwest Ethiopia.

Methods: Health institution based cross-sectional study was conducted in Yem Special Woreda, Southwest Ethiopia. A simple random sampling technique supplemented with Focus Group Discussion was used. Data was collected using pre-tested structured questionnaires. SPSS version 20.0 was used for Bivariate and Multivariate Analysis.

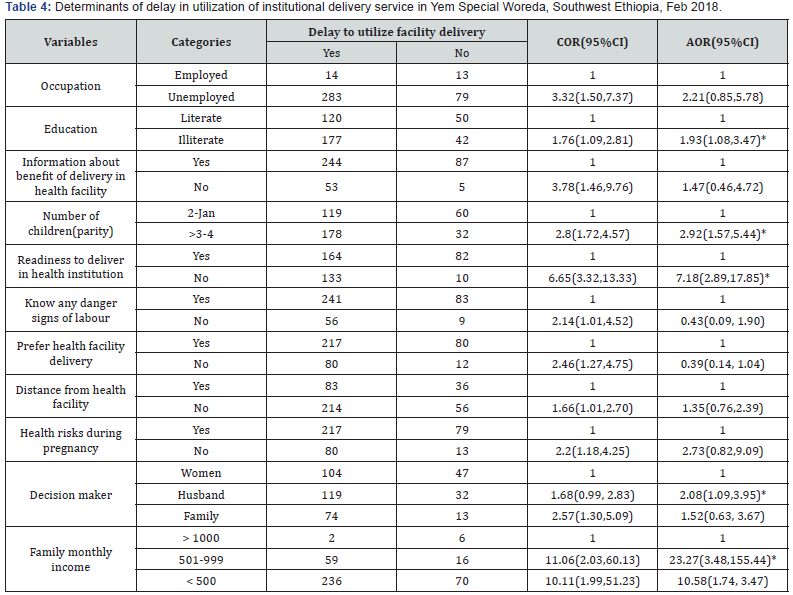

Result: The prevalence of delays in delivery service utilization was 76.3%. The mean time delay to utilize institutional delivery service was 5(±3.08) hours. Low educational status of women (AOR=1.9, 95%CI: 1.09, 3.47), Parity (AOR=2.9, 95%CI: 1.57, 5.44) and Husbands decision (AOR=2.08, 95%CI=1.09, 3.95) were found to be significantly associated with delay to utilize institutional delivery services.

Conclusion: Low educational status of women, parity, not being ready to give birth in health facility and husband’s decision making were found to be determinants of delay to utilize institutional delivery services.

Abbreviations: AOR: Adjusted Odds Ratio; EDHS: Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey; FGD: Focus Group Discussion; FMOH: Federal Ministry of Health; MCH: Maternal and Child Health; SPSS: Statistical Package for Social Sciences; SNNPR: Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples Region; Ethical approval and consent to participate

Keywords: Delays; delivery service utilization; Yem Special Woreda; Ethiopia; Maternal death; Data collectors; Logistic regression analysis; Pregnant women; Midwives; Life threatening; Safe birth; Geographical inaccessibility; Field supervisors; Investigators; Statistically significant; Motivation; Physical access

Introduction

Institutional delivery service is one of the key and proven interventions to reduce maternal death. It ensures safe birth, reduce both actual and potential complications and maternal death and increase the survival of most mothers and newborns. But most deliveries in developing countries occur at home without skilled birth attendants. The 2014 EDHS report revealed that 83.4% deliveries took place at home whereas only 15.4% of deliveries were institutional [1]. Maternal deaths are strongly associated with delays to utilization of institutional delivery service and inadequate medical care at the time of delivery. Several factors have been identified as barriers to early access to skilled care by women especially in developing countries; these include perceived quality of care at health facility, inadequate number of skilled personnel, geographical inaccessibility and financial constraints, decision making power, awareness on danger sign of pregnancy and benefit of utilizing institutional delivery services [2]. Even with the best possible antenatal care, it is established that delivery could be complicated and timely utilization of institutional delivery service is essential to safe delivery care [3]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to assess the delays in utilization of institutional delivery service and its determinants in Yem Special Woreda, Southwest Ethiopia.

Methods and Materials

Study area and period

The study was conducted in Yem Special Woreda, Southwest Ethiopia, from Feb 03-28/2018.Yem Special Woreda is located 297 KMs southwest of Addis Ababa. It has three towns and 34 kebeles (the smallest administrative units) with an estimated population of 99,714; of these 50,854 were male whereas 48,860 were females (Projected from 2007 National Census).There were six Health Centres namely Fofa Health Centre, Semonam Health Centre, Saja Health Centre, Toba Health Centre, Deri Health Centre and Gesi Health Centre. Besides, there were 27 Health Posts in the Woreda.

Study design

Health institution based cross sectional study design was used.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion: All women who visited the six health centers for delivery service were included.

Exclusion: All women who were severely sick and unable to respond during data collection period and women who utilized maternal waiting home were excluded.

Sample size determination

For quantitative study: The sample size was calculated using single population proportion formula. The prevalence of first delays in utilizing institutional delivery service 37%(P=0.37) [4], 5% margin of error, 95% confidence level and 10% non response rate were considered. Thus, the total sample size was calculated to be 393.

For qualitative study: A total of eight Focus Group Discussions were conducted. Of these; six FGDs were conducted with MCH service user women whereas two FGDs were conducted with service providers in selected two health centers.

Sampling technique

For quantitative study: The required total sample size was proportionally allocated to the six Health Centers based on their previous three months delivery load. Accordingly, the allocated sample was 94 for Fofa HC, 52 for Semonam HC, 75 for Saja HC, 62 for Toba HC, 56 for Deri HC and 54 for Gesi HC. All pregnant women who utilize institutional delivery service in each health center during data collection period were included in the study until the required sample size was fulfilled.

For qualitative study: Delivery care providers such as nurses and health officers who wereworking at the public health centers and women who camefor MCH services during the data collection period were purposively included in the FGDs. Participants interviewed in the quantitative survey were excluded from the FGD.

Data collection tool and procedure

For quantitative study: Pre-tested structured questionnaire was used to collect the data. The instrument was adopted from JHPIEGO tools and indicators for maternal and neonatal health [5]. Seven health professionals and three supervisors including the principal investigators were participated in the data collection. Half a day orientation was given to the data collectors and supervisors on the data collection tools and procedures by the principal investigators.

For qualitative study: Semi-structured FGD topic guide was used to facilitate the discussion. Each of eight FGDs had 6-12 participants and a total of 72 participants (i.e. 59 service users and 13 service providers) were involved. Each FGD spend 45-60 minutes. Written notes were taken and all the discussions were tape recorded.

Data quality control: The questionnaires were translated from English into the local language (Amharic) & vice versa. A pre-test was conducted on 5% of the sample. Data collectors were well trained. Daily supervision was conducted by the field supervisors and investigators.Supervisors used to check all procedures and completeness of formats randomly. Data were checked before entry. Qualitative records were transcribed carefully in themes and interpreted.

Data processing and analysis

For quantitative study: Data was analyzed by SPSS for windows version 20. Bivariate logistic regression model was fitted as a primary method of analysis. Then, variables having P-value <0.25 were entered into multivariate logistic regression analysis using the forward LR method. Finally, P-value <0.05 in multivariate analysis was used to declare statistically significant variables.

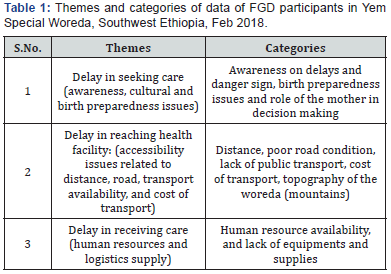

For qualitative study: Written notes from all 8 FGDs were compiled and labelled according to participants’ type. After reviewing individual FGD transcriptions, data was organized according to the themes and summarized manually. The result was presented in narratives triangulated with the quantitative results (Table 1).

Definition of terms

Delays in utilization of institutional delivery service: Refers to the time taken more than one hour to make decision to seek care or more than one hour to reach health facility after making decision or waiting for more than one hour in health facility to receive delivery care.

Delay in making decision to seek care: Refers to the time taken ≥1 hour to make decision to seek care was considered as delay and less than an hour considered no delay.

Institutional delivery utilization: when a mother gave birth at health institution and the delivery was assisted by skilled birth attendant or trained health professional.

Result

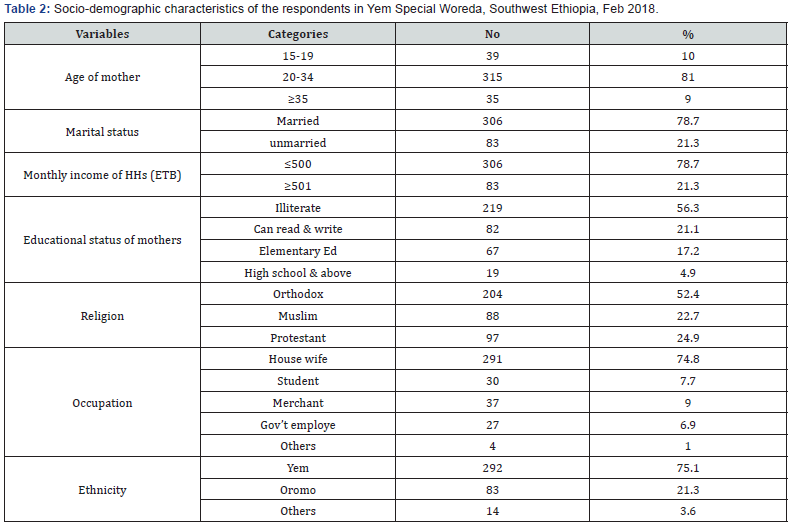

Socio-demographic characteristics

A total of 389 respondents involved in the study yielding 98.9% response rate.The mean age of the study participants was 26(±5). Majority of the respondents, 292(75.1%) were Yem in ethnicity. Orthodox Christian, 204(52.4%), was the dominant religion.About 306(78.7%) of mothers were married. Besides, 291(74.8%) of the study participants were house wife whereas 27(6.9%) were Government employees. Two hundred nineteen (56.3%) of them cannot read and write (Table 2).

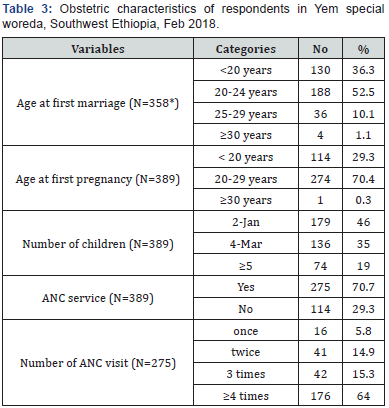

Obstetric characteristics

About 275(70.7%) of the study participants reported utilization of ANC services. One hundred sixty nine (43.4%) and 142(36.5%) of study participants faced maternal complications during previous and current pregnancies, respectively. With regard to decisions; 151(38.8%) of women decide themselves, 151(38.8%) decide by their husbands and 87(22.4%) decide by their family members to utilize delivery service (Table 3). Besides, 297(76.7%) subjects preferred health facility delivery whereas the rest 92(23.7%) did not prefer the same. The reported reasons for not preferring health facility delivery were 11(12.1%) fear, 16(17.6%) lack of money, 40(44.0%) distance and 24(26.4%) poor treatment from professionals.

Delays in utilizing institutional delivery services

The prevalence of delay to utilization of institutional delivery service in the study area was 76.3% and the mean (±SD) of delay time to utilization of delivery service was 5(±3.08) hours. About 172 (44.2%) respondents reported they faced problems on making decisions to utilize delivery services from health facilities. One hundred sixty-eight (43.2%) respondents reported that they have transportation problems. The study showed 198(50.9%) travelled on foot, 101(26%) were carried by wooden stretcher and the rest 90(23.1%) travelled by car to health facility.The qualitative result showed that, distance and poor road conditions made it virtually impossible for many pregnant women to reach the health facility. In some instances, inadequate or inappropriate transport made it difficult for women to reach the health facility. In the rural areas, the common means of transport is foot; in hills and mountain districts, people carried pregnant women to the health facility on stretchers. Pregnant women faced difficulties in reaching the health facility, especially at night or during rainy seasons. This is supported by the qualitative finding that a 30 years old woman from “Toba kebele” commented: “....It is particularly difficult if the labor begins at night. There is no transport facility and the way is dark. In such a situation, how can we go to the health facility to utilize delivery service..?....”.Other participants of the FGDs also further suggested that lack of transport, long distance from facilities and absence of delivery care centers appear to be significant contributory factors for delay to seek delivery services. From the FGDs we understood that, women who travelled the shortest distance had a high chance of attending and coming early to utilize delivery care from health centers whereas women who were travelling long distances had little chance to seek treatment as early as possible.

About 276 (71%) of the respondents reported that they were happy with the service provided and the rest 113(29%) unhappy. Lack of drug 5(4.4%) and poor treatment from professional 108(95.6%) were making them unhappy to the service provided by the health facility. In support of this the qualitative result showed that there were shortages of midwives and staffs high work load in the health facilities.Due to these, the women waited for long time to utilize delivery service after they reached at health facility. The following two participants of the FGDs suggest the same. A 27 years old Nurse, service provider, from ‘Gesi Health Centre’ commented: “Only one Midwife is available in most of the health facilities in the woreda, thus when she is on leave, in training or transferred to another health facility, women cannot get timely delivery service from the health facility. And also when the number of deliveries exceeded ability to provide services and staff members became overburdened.” Besides; a 34 years old, Health officer, from the same health centre said that “The absence of a clear division of roles among staff members who shared responsibility for providing maternal health services further aggravated this situation and affected worker motivation and performance. This condition leads to delays in utilizing delivery service.” Hence, lack of qualified health professionals and absence of clear job divisions among workers contributes for delay in institutional delivery services.

Determinants of delays in institutional delivery service utilization

The multivariate logistic regression analysis revealed that Parity or having three or more children, not being prepared for birth, low educational status of mothers, and decisions made by husbands were significantly associated with delay in utilization of institutional delivery services. Accordingly, women whose husbands make decisions were two times (AOR= 2.08, 95%CI=1.0, 3.9) more likely to delay in utilization of institutional delivery services as compared to those who make decisions by themselves (Table 4). In support of this finding, a 30 years old mother from Gesi kebele said: “Many husbands do not allow their wives to visit the health facility for seeking delivery services because of traditional beliefs. Women cannot ignore their husbands’ decision and cannot express their opinion in the family”. Hence, it is clear that women who make decisions by themselves free of their husbands influence are more likely to use institutional delivery services on time. The study also revealed that, women who have three or more children are 3 times (AOR= 2.9, 95%CI= 1.57, 5.44) more likely to get delay in utilization of institutional delivery services as compared to those who have two or less children (Table 4). A 42 year old woman from Deri kebele commented that “………..I have four children. They are students and I am caring about their school. I am a house wife and my husband is a farmer. We are responsible for their school performance and economic issues. We did not have money at hand, so I was late in my last birth while my husband was looking for borrowing money for transportation....” Here, from the opinion of woman above, we can deduce that having more children affects the economy of family and in turn causes delay in institutional delivery service utilization.

Discussion

The study assessed delays in utilization of delivery services and its determinants. The prevalence of delays in delivery service utilization was 76.3%. This finding was higher than the finding from a study in rural Bangladesh [6]. This might be due to the existence of differences in accessibility of health facilities and delivery service utilization culture of the community. Regarding physical access to health facility, about 69.4% were found to have no access to health facility or live in a walking distance of greater than one hour and the mean walking distance from their homes was two hours. This finding was slightly higher than findings from studies in selected developing countries by Babinard [7]. The possible reason may be large distances between health institutions due to the sparse pattern of the population in the study area.Besides, this finding was consistent with findings from the 2011 EDHS report in which 66% of mothers did not have access to or live in a walking distance of more than one hour from institutional delivery services in Ethiopia [8]. This is supported by findings from the qualitative study in that most of the participants said they walk a long distance to reach health facilities. Besides, the study revealed that 34.7% of the mothers waited for more than one hour to utilize institutional delivery service after they arrived at health facility. This finding was higher than the findings from a study in Bahir Dar, Ethiopia [9].

The qualitative finding showed that long time admission process, staffs work load and lack of supplies were the main reasons for third delay to utilize institutional delivery service at health facilities.Further the study showed that women whose husbands make decisions were two times more likely to delay in utilization of institutional delivery services as compared those make decisions by themselves. This finding is consistent with the findings from studies in rural Bangladesh and Bahir Dar Ethiopia [6,9]. This also was supported by the qualitative findings in that most of the participants of the FGDs argued that male dominance for decision and not being prepared for delivery was the main reasons for delays in utilizing delivery services. The participants also added unless labour is complicated husbands would not allow their wives to visit health facilities. Delay in utilizing delivery service was seven times more likely among mothers who were not being prepared for institutional delivery as compared to those prepared mothers. This finding was consistent with the cross-sectional study in Kenya and Ethiopia [10,11]. The qualitative study showed that participants did not think it was necessary to go to a health facility for normal delivery unless they experienced a serious problem.

Women who have three or more children were three times more likely to delay in utilization of delivery services as compared to mothers who have two or less children. This finding is consistent with the findings from studies in Bangladesh and Nigeria [12,13]. The possible reason could be the fact that women who have higher parity develop experience and confidence regarding child birth, and hence might delay to utilize delivery services.On top of this, the study indicated that women with low education status were two times more likely to delay in utilization of institutional delivery services as compared to that of literate women. This finding was consistent with the various studies in Nigeria & Nepal [12,14]. The reason could be for educated women might have better access to information about the advantages of institutional delivery and pregnancy related complications.

Conclusion

The prevalence of delays in delivery service utilization was 76.3%. Low educational status of women, parity, not being ready to give birth in health facility and husband’s decision making were found to be determinants of delay to utilize institutional delivery services.

Recommendation

Federal Ministry of Health in collaboration with other stakeholders should promote women education. Regional Health Bureaus’ and Zonal Health Departments’ should strongly advocate the utilization of institutional delivery services. Besides, Woreda Health Offices in collaboration with local government bodies and other stakeholders should work hard to improve the awareness of women on institutional delivery.Ethical clearance letter was obtained from department of Public Health, Mizan- Tepi University. The participants were made aware about the purpose of study, and oral consents were obtained accordingly. The participants’ right to refuse or withdraw from the study and confidentiality issues were considered.

Acknowledgment

First of all, our deepest gratitude and appreciation goes to Department of Public Health; College of Health Sciences, Mizan- Tepi University. We would also like to extend our gratitude to Yem Special Woreda health office staffs and the health centres staffs for their cooperation in data collection. Finally, our great appreciation goes to the data collectors and supervisors.

References

- Central Statistical Agency (2014) Ethiopia Mini Demographic and Health Survey 2014. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Mohammed T (2002) Making pregnancy safer: A strategy for action. Safe Motherhood Newsletter.

- WHO (2008) Proportion of births attended by skilled attendantupdates. Department of reproductive health and research, World Health Organization Geneva, Switzerland.

- Worku Awoke, Kenie Seleshi (2013) Maternal delays in utilizing institutional delivery services, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

- JHPIEGO (2004) Maternal and neonatal health. Monitoring birth preparedness and complication readiness, tools and indicators for maternal and newborn health.

- Killewo J, Anwar I, Bashir I, Yunus M, Chakraborty J (2006) Perceived delay in healthcare-seeking for episodes of serious illness and its implications for safe motherhood interventions in rural Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr 24(4): 403-412.

- Babinard J (2006) Transport for health in developing countries.

- Central Statistical Agency [Ethiopia] (2011) Ethiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2011, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Worku Awoke, Kenie Seleshi (2013) Maternal delays in utilizing institutional delivery services, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia.

- Mona M, Rebecca C, Isabella C, Donna P, Marcia G (2002) A behavior change approach to investigating factors influencing women’s use of skill care in Homa Bay District Kenya, the change project. Academy for educational development.

- Mihret H, Mesganaw F (2006) Birth Preparedness and Complication Readiness among women in Adigrat town, Tigray Region, North Ethiopia.

- Edmonds JK, Paul M, Sybley L (2012) Determinants of place of birth decisions in uncomplicated childbirth in Bangladesh: an empirical study. Midwifery 28: 554-560

- Odimegwu C, Adewuyi A, Obediyi T, Aina B, Adesina Y, et al. (2005) Men’s role in emergency obstetric care in Osun State of Nigeria. Afr J Reprod Health 9: 59-71.

- Heer T (2009) Determinants of home delivery in semi urban settings of Nepal Medical College Teaching Hospital.