Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation within a generation: what worked and what next?

Oto Buraimo1* and Olatunji Sonoiki2

1Brymore Public Health, Nigeria

2World Food Programme, Nigeria

Submission: February 06, 2018;Published: April 30, 2018

*Corresponding author: Oto Buraimo, Brymore Public Health, Nigeria, Email: oto.buraimo@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Oto Buraimo,Olatunji S.Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation within a generation: what worked and what next?. Glob J Reprod Med. 2018; 4(4): 555641. DOI:10.19080/GJORM.2018.04.555641.

Abstract

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) involves the non-therapeutic partial or complete removal of external female genitalia for non-medical reasons but largely due to cultural, religious and social reasons. Besides the obvious physical agony experienced by women subjected to FGM/C, the practice of FGM/C is still endemic in about 29 countries in Africa, Asia and Middle East, and worldwide due to international migration. Over 200 million are affected, 3 million girls and women stand the risk of undergoing FGM/C annually and more recent statistics show that 15 million girls are at risk of undergoing FGM/C by 2020 in the absence of apt intervention.

An understanding of the drivers of FGM/C is an invaluable first step at ending the crisis, so we highlighted the drivers of this age-long practice and expounded creditable interventions amongst home-based and foreign-based indigenes of communities where FGM/C is highly prevalent. Subsequently, we propose that interventions must be comprehensive and holistic and context-relevant.

Keywords: Female genital mutilation/cutting; Female circumcision; Sexual and reproductive health; Harmful practices; Religious; Social reasons; Clitoridectomy; Infibulations; Psychological; Emotional scars; Chronic infection; Recurrent pains; Urination and menstruation; Obstetric complications; Sexual desire; Globalisation; Perpetuators; Marriage ability; Peulh ethnicity; Sexual morals; Health hazards; Positive reinforcement; Sensitive

Abbreviations: FGM/C: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting; WHO: World Health Organisation.

Introduction

Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) also known as ‘female circumcision’ or ‘female cutting’ involves the non-therapeutic partial or complete removal of external female genitalia for non-medical reasons but largely due to cultural, religious and social reasons [1]. The World Health Organisation (WHO) has broadly classified FGM/C into four types: clitoridectomy, excision, infibulations and other [2]. The act remains a gross human rights violation specifically against girls and women in their early adolescence. Besides the obvious physical agony experienced by women subjected to FGM/C and death in certain cases, the act leaves detrimental lifelong psychological and emotional scars including chronic infection, recurrent pains during sexual intercourse, urination and menstruation and obstetric complications during childbirth [3]. A systematic review of comparative studies between women with FGM/C and without FGM/C concluded that those with FGM/C are more likely experience pain during sexual intercourse and reduced sexual desire and satisfaction, which completely deprives the victims of FGM/C optimum control over their sexuality [4].

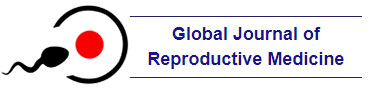

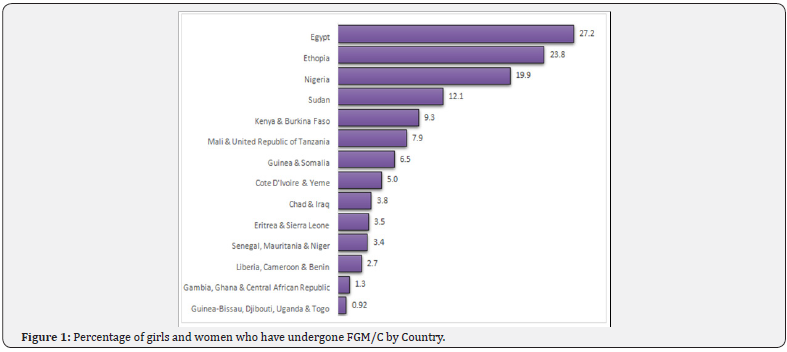

Although the practice of FGM/C is endemic in about 29 countries in Africa, Asia and Middle East, victims are scattered across the globe largely due to globalisation and international migration. The findings from a UNICEF led national survey in over 35 countries show that over 200 million women have undergone FGM/C, a practice which is disproportionately rife in countries like Somalia, Guinea, Djibouti and Egypt where over 90 percent of girls and women aged 15 to 49 years have undergone FGM/C at some point in their lifetime [5] (Figure 1). In absolute numbers, Egypt, Ethiopia, Nigeria, Sudan, Kenya and Burkina Faso account for almost 100 million (approximately 50 percent) of the entire global cases of FGD (Figure 2). Moreover, 3 million girls and women stand the risk of undergoing FGM/C annually and more recent statistics show that 15 million girls would have undergone FGM/C by 2020 in the absence of apt intervention, which will invariably aggravate the already troubling statistics of girls and women that are managing the lifelong consequences of FGM/C [6,7].

Oftentimes, perpetuators perceive this dangerously life altering act as a way to curb promiscuity and invariably promote fidelity among FGM/C victims [3]. Other underlying reasons for the practice of FGM/C relates to the promotion of the marriage ability of girls and preservation of their virginity in order to prevent shame following marriage and as well enhance social acceptance within communities where the practice of FGM/C is rife [8,9]. The practice of FGM/C has ethnicity and religious dimension likewise as observed in the countries like Benin, Togo and Niger. In Benin, girls and women with Peulh ethnicity are seven times more likely to undergo FGM/C compared to counterparts from Adja and Fon ethnicity. Moreover, Muslim girls and women are more likely to undergo FGM/C compared to Christian counterparts in Togo whereas Christian girls and women are more likely the experience the same in Niger.

Why female genital mutilation/cutting continues

Despite the lifelong adverse effect of FGM/C on the physical and mental health, girls and women that have undergone FGM in countries like Gambia perceive the practice as being beneficial and hence want FGM/C to continue. Also, FGM/C survivors with lower levels of literacy in Sudan and Ethiopia support the continuation of FGM/C, which demonstrates how ingrained the practice remains within some communities [5]. An understanding of the drivers of FGM/C is an invaluable first step at ending the crisis. In two systematic reviews of 51 studies involving home-based and foreign-based indigenes of communities where FGM/C is highly prevalent, cultural tradition, religious beliefs, and sexual morals were the reasons for the continuance of the practice [10,11]. The cultural, social, ethnic and sometimes religious underpinnings of FGM/C bring the complexities of eradicating the practice to the foreground. This potentially explains the persistent practice of FGM/C despite concerted eradication efforts by global advocates, policy makers and national governments. Nonetheless, these efforts have yielded marginal returns as the prevalence of FGM/C has declined steadily over the last three decades despite the burgeoning global population growth within the same period [6].

Interventions that have worked

Interventions toward abandonment of FGM/C have adopted many approaches. Some of the widely evaluated methods are community-led approaches, public declarations, conversion of excisers, alternative rituals, training of health workers as change agents, health hazards approaches, and legal sanctions [12,13].

Community-led approaches: They focus on empowering girls, women and community members to self-examine their cultural practice of FGM/C and abandon it for their own benefit [14]. Success of this approach is usually context-dependent. For example, a similar programme run in paired communities Senegal, Burkina Faso and Somalia resulted in markedly different rates of FGM/C abandonment across the three countries [10,15,16].

Public declarations: These are open statements by a large group in a community to abandon FGM/C. These declarations can signify a readiness to change or an actual abandonment of FGM/C. However, public declarations are rewards of effective intervention, programmes that solicit statements from authoritative subgroups such as eminent religious leaders or excisers rarely results in behavioural change if the community buy-in is low [12].

Conversion of excisers: Some interventions target excisers, majority of whom are traditional practitioners, with the aim of training them on female anatomy and the hazards of FGM/C and convincing these practitioners to stop performing FGM/C. Subsequently, ex-excisers are rewarded with training and funding for alternative source of livelihood. Although this approach offers an easy measure of the success of intervention, an ex-practitioner may return to the trade covertly or by proxy and other aspiring exciser may fill the vacant positions [17].

Alternative rituals: Many communities perform FGM/C as a part of rite of passage from childhood to womanhood for their adolescent girls. Alternative rites interventions proffer a replacement of FGM/C-included rite of passage with alternative rite while still upholding the tradition of the community. For example, in Kenya and Sierra Leone, excising rituals were replaced non-cutting versions during the ritual seasons [18]. However, the use of alternative rites are limited to context where FGM/C is part of rite of passage and not elsewhere.

Health hazards approaches: The health risks of FGM/C are communicated via health information materials and media. It is the oldest and most popular method whereby individuals and community groups are informed on the health hazards of FGM/C by lay workers, health personnel, community facilitator or civil society staff [19]. The increased knowledge are expected to stimulate critical thinking that will eventually foster an abandonment of FGM/C [20]. Poorly formulated, judgmental and ‘westernised’ health information have been linked with disbelief, resistance, defence reaction, outright disregard and medicalization of FGM/C [21].

Training of health workers as change agents: Health professionals are influential members of the community that can foster healthy changes. Thus, intervention have focused on health workers with the aim of educating them on FGM/C, preventing them from practicising it, training them on identifying and treating associated complications, and ultimately deploying them as change agents [22]. However, some health workers might be resistant to abandoning FGM/C owing to their socio-cultural beliefs. In fact, the literature is rife with medical proponents of FGM/C [23,24].

Legal sanctions: Legislative measures against FGM/C have been adopted in many communities to prevent FGM/C. Numerous African and Western countries have formally enacted laws that ban FGM/C and impose prosecutions, punishment and/ or fines [25,26]. Laws may make FGM/C go underground and may also deter sufferers of immediate complications of FGM/C from seeking prompt medical treatments [27].

What we can do differently

Throughout the four decades that interventions against FGM/C have been ongoing, many successes have been achieved, yet a lot more ground awaits covering. Findings from research have shown that ‘a one size fit all’ approach will not accelerate the progress towards elimination of FGM/C. Contrariwise, interventions that have worked have been those that mobilised multi-sectors, assembled many actors, ran from and with the community, and ensured sustained actions [2]. Therefore, programmes should be comprehensive and holistic; methods should anchor on a background of community participation and involvement; sensitive, tailored, locally relevant health information should be used as a tool to foster change; positive reinforcement should be supplied from a network of religious and community leaders, health professionals and peer group incorporate; and an FGM/C supportive legal framework should be enacted and enforced at all level of governance.

Conclusion

Many individuals, agencies and organisations have conducted research and are planning more studies. For example, since 1996, the Population Council with its partner partners like DFID, USAID, UN Agencies, Wallace Global Fund, Comic Relief and Norad have focused on research in 13 countries where FGM/C is highly prevalent [28]. However, scores of research gaps are still evident, studies designs need to improve, and research should comply with internationally agreed indicators [29]. Finally funding fuels progress and many funding agencies have helped with the progress on eliminating FGM/C so far, but funding gaps still need to be filled and very quickly too [2].

References

- World Health Organization (2016) WHO Guidelines on the management of health complications from female genital mutilation Geneva, Switzerland.

- World Health Organization (2008) Eliminating Female genital mutilation An interagency statement. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Equality Now (2018) Know the Facts: What is Female Genital Mutilation (FGM)?| Equality Now n.d.

- Berg RC, Denison EML, Fretheim A (201) Psychological, social and sexual consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C): a systematic review of quantitative studies.

- Mohammed GF, Hassan MM, Eyada MM (2014) Female genital mutilation/cutting: A statistical overview and exploration of the dynamics of change 11(11): 2756-2763.

- UNICEF (2018) Female genital mutilation/cutting: A global concern - UNICEF DATA 2016.

- Population Reference Bureau. Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting: Data and Trends n.d.

- Fourcroy JL (2006) Review: Customs, Culture, and Tradition-What Role Do They Play in a Woman’s Sexuality? J Sex Med 3: 954-959.

- Avalos L, Farrell N, Stellato R, Werner M (2015) Ending Female Genital Mutilation & amp; Child Marriage in Tanzania. Fordham Int Law J 1: 25.

- Berg RC, Denison E (2012) Interventions to reduce the prevalence of female genital mutilation/ cutting in African countries 2012.

- Berg RC, Denison E (2013) A tradition in transition: factors perpetuating and hindering the continuance of female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C) summarized in a systematic review. Health Care Women Int 34(10): 837-859.

- Johansen REB, Diop NJ, Laverack G, Leye E (2013) What Works and What Does Not : A Discussion of Popular Approaches for the Abandonment of Female Genital Mutilation 1: 10.

- Brown K, Beecham D, Barrett H (2013) The Applicability of Behaviour Change in Intervention Programmes Targeted at Ending Female Genital Mutilation in the EU : Integrating Social Cognitive and Community Level Approaches 2013: 13.

- GTZ (2001) Addressing Female Genital Mutilation. Challenges and Perspectives For Health Programmes. Part I: Selected Approaches 2001.

- N. Diop and I. Askew. Strategies for encouraging the abandonment of female genital cutting: experiences from Senegal, Burkina Faso and Mali,”. Female Circumcision Multicult. Perspect. - Google Books, Philadelphia, USA: 2006, p. 125-141.

- https://www.unicef.org/somalia/resources_11628.html

- http://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/fgm/dhs_ report/en/

- YH-F (2000) circumcision in A, change undefined, 2000 undefined. Cutting without ritual and ritual without cutting: female circumcision and the re-ritualization of initiation in The Gambia.

- Toubia NF1, Sharief EH (2003) Female genital mutilation: have we made progress? Int J Gynaecol Obstet 82(3): 251-261.

- Kaplan A, Forbes M, Bonhoure I, Utzet M, Martín M, et al. (2013) Female genital mutilation/cutting in The Gambia: long-term health consequences and complications during delivery and for the newborn. Int J Womens Health 5: 323-331.

- AH-F (2006) circumcision: A community of women empowered: The story of Deir El Barsha.

- Berg RC, Denison E (2012) Effectiveness of interventions designed to prevent female genital mutilation/cutting: a systematic review. Stud Fam Plann 43(2): 135-146.

- Kandil M (2014) Female circumcision : Limiting the harm. F1000Research Search 1: 1–10.

- Conroy RM (2006) Female genital mutilation: whose problem, whose solution?. BMJ 333(7559): 106-107.

- Doucet MH, Pallitto C, Groleau D (2017) Understanding the motivations of health-care providers in performing female genital mutilation: an integrative review of the literature. Reprod Health 14(1): 46.

- Odukogbe AA, Afolabi BB, Bello OO, Adeyanju AS (2017) Female genital mutilation/cutting in Africa. Transl Androl Urol 6(2): 138-148.

- World Health Organization (2014) WHO|Female genital mutilation: programmes to date: what works and what doesn’t.

- Population Council (1996) A Research Agenda to End Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting (FGM/C) in a Generation| Population Council.

- UNICEF (2005) Changing a Harmful Social Convention: Female Genital Mutilation/Cutting.