Surgical Medicamentous Approach to the Treatment of the Contact Point Headache

Novak Vukoje* and John Garito

ENT office "dr Vukoje", Petrovaradin, Serbia

Submission: February 22, 2018; Published: March 14, 2018

*Corresponding author: Novak Vukoje, ENT office "dr Vukoje”, Petrovaradin, Serbia, Email: drvukoje@hotmail.com

How to cite this article: Novak Vukoje, John Garito. Surgical Medicamentous Approach to the Treatment of the Contact Point Headache. Glob J Oto 2018; 13(4): 555870. DOI: 10.19080/GJO.2018.13.555870

Keywords

Keywords: Contact point headache; Surgical treatment; Medicamentous treatment

Introduction

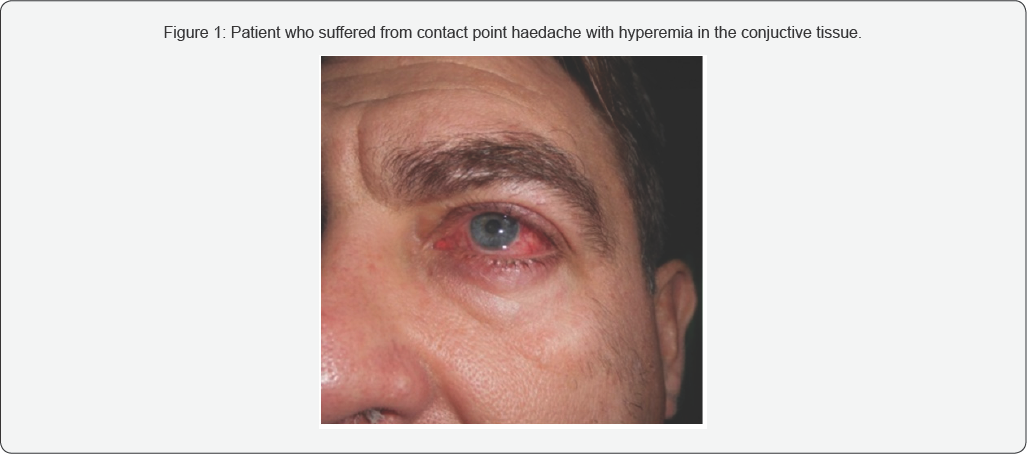

In the field of head and neck, primary pain is most often caused by neuralgia of the fifth cranial nerve / n. tigeminus/ glossopharyngeal nerve, occipital nerve/occipital headache/, and the secondary pain as headache is usually caused by inflammation ofthe sinus. Also carious teeth can cause unbearable pain. Diagnosis requires more consultative collaboration with a number of medical specialties of diagnostic procedures. One of the rare unusual headaches, known as contact points headache, in addition to diagnostic and represents a considerable therapeutic problem. That is one of the reasons why patients wander for years without diagnosis and adequate treatment. It is described by Sluder in 1908 and it was named Sluders neuralgia, after him. Headache characterized by attacks of severe, sharp, unbearable and unilateral pain that is usually focused in the area of the side wall of the nose and the corners of the eye, which belongs to the inervation anterior etmoidal nerve. Common causes are: compression and irritation of the terminal branches of the said nerve which is «pinched» between the two structures of the nasal mucosa. The contact between the mucosa of the upper, lower and middle turbinate, concha bullosa, ethmoidal sinusitis on one side and spur or deviation of the nasal septum on the other hand, are mostly responsible for this pathology. Pain attacks may occur, and up to 8 times per day, with a time duration of 15-180 minutes during day (Figure 1). Sometimes were combined with ipsilateral hyperemia in the conjunctiva, ptosis, miosis and lid edema accompanied had epiphora. The attack is often preceded by a cold, nasal obstruction and rhinorrhea.

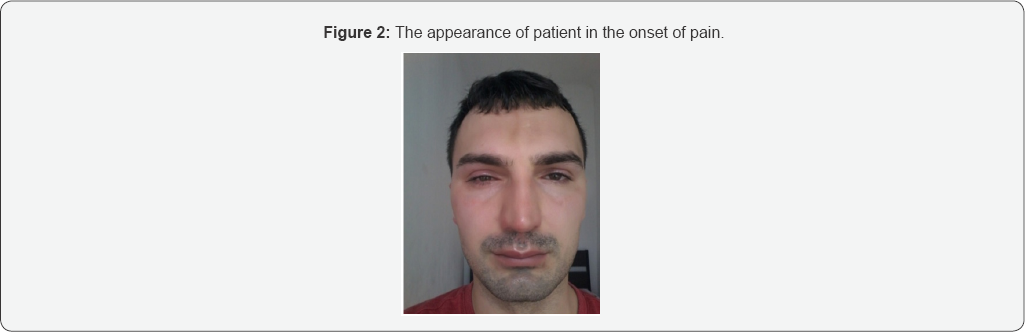

Contact point headache is three times more common in men than in women (Figure 2). The question is why about 60% of the population with mucosal contact has no headache. Why Cephalia has appeared now and the curve nasal septum with mucosal contacts lasts for years. It is believed that with time, the nerve that is «compressed» between the two structures becomes hypersensitive, and transitions into a neuropathy that leads to local pain. Pathophysiology of pain refers to mediators, neuropeptides, calcitonin, substance P, etc. which are thought to cause vasodilatation and edema ofthe nasal mucosa in addition to the central mechanism, which further aggravates the symptoms. What’s typical for this headache is that the pain starts after a cold and viral infection of the upper respiratory tract. It can be associated with sensitivity to light or noise and is therefore noticed as a migraine without aura. CT and MRI headaches are usually neat, and often headaches are attributed to psychic status. In the absence of nasal symptoms, patients are most likely to have a neurologist who prescribes medication therapy, which is generally unsuccessful. If headache is associated with sensitivity to light or noise, it is usually diagnosed as a migraine without aura [1,2]. Temporary and occasional presence of contact points that are compatible with the nasal cycle can trigger this type of headache (Figure 3).?

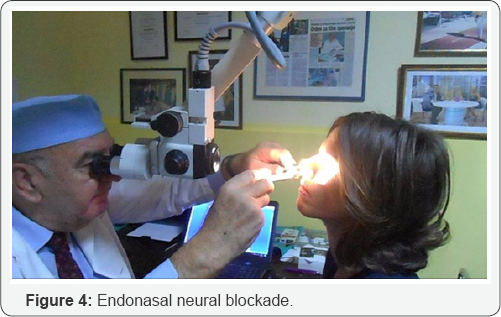

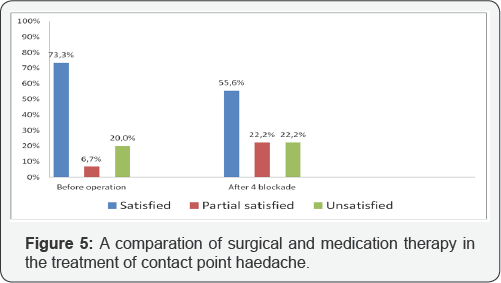

The remaining nine (37.5%) were treated with Xylocain- dexasone in the projection of the distribution of the front etmoidal nerve through four sessions at intervals of 2-3 weeks. The evaluation of the effectiveness of treatment was done based on the VAS scale three and six months after the treatment. Results: Out of 15 surgical cases, 11 (73.3%) were satisfied with the procedure, one was partially satisfied, and in three cases there was no improvement (Figure 4). Of 9 patients treated with nerve blockage after four sessions in 5 (55.5%), the pain was significantly reduced or missing, in two (22.2%) decreased, and the other two were the same.

Discussion

Chronic pain in the head and neck occurs in about 10-15% of the adult population. After long and often inadequate treatment, many patients suffer from severe pain for years as it can lead to depression. Frequently changing doctors, therapy, resort to selftreatment, they seek refuge with the quacks. Each of pain in this region requires specific diagnostic and cure. Each of the pains in this region requires specific diagnosis and treatment. It should be noted that the treatment of chronic pain in the headache is individually and that there is no single approach, method and medication for all patients, nor do all patients receive the same treatment. For this reason, the treatment of pain is performed by various specialists: neurologists, dentists, oral surgeons, neurosurgeons, otorhinolaryngologists, and others. Head CT scan and MRI usually do not reveal any pathology, and the diagnosis that is reported to the patient suggests that this headache is a result of a psychological problem or is a kind of neuropathy [3,4].

To alleviate pain, doctors prescribe a number of analgesics, drugs for neuropathy, narcotics, steroids, muscle relaxants, etc. All of these drugs do not relieve headaches of the contact point [5-7]. The only medications that have a temporary positive effect in the relaxation of pain are from the group of decongestants. They reduce the existing lining of the mucosa and thereby prevent mucosal contact and at the same time eliminate nerve compression. Since their effect is time-limited, a new recurrence of mucous membrane edema leads to pain relief (Figure 5).

Since the cause of contact headache headaches is nerve compression caused by structural abnormalities that can be corrected surgically, surgery remains the only optimal treatment that can eliminate the anatomical structures that induce this pathology [8-11]. Surgical treatment of the headache of the contact point usually involves correction of the nasal curvature, removal of spina or cutaneous septum, reduction of enlarged nasal bumps, resection of blue etmoidal or removal of other anomalies depending on which deformities make mucous contact and pressure nerve. The goal of this surgery is to create more space in the nose and to prevent any pressure on the nerve when the mucous island appears. There are several studies that have analyzed the success of the headache operation of the contact points. The inclusion criteria and results were different from studies to studies. The largest series, presented by Huang and associates [7], included 66 patients divided into three groups: with deviation of the nasal septum, bulge congestion and an overburden orbitoetmoidal Halle cell. After surgical treatment, the authors found a decrease in intensity and incidence of headache in 88.8% of patients. Parsons and Batra [8] in a retrospective study involving 34 people with mucosal contact between the septum and nasal bumps after surgery noted a progression of 91%. Sadeghi and others [12] published similar results (improvement of 93.3% of patients) on a similar sample for 30 patients. Peric and associates [10] point out success in over 88% and state that patients do not need any treatment after surgical treatment. In a study published by Welge-Luessen et al. [13], referring to 20 patients with headaches caused by contact between the middle nasal bumps and nasal septum, or between middle nasal bumps and blue etmoidal, after observation of 10 years, found that the improvement rate from 85% fell to 65 %. This result points to the conclusion that the selection criteria for these patients should be better standardized and that the patient’s monitoring period after the surgical procedure should cover a longer period of time. Our results, with an improvement rate of 73.1%, are generally somewhat lower than the results of other authors. The reason should be sought in pain pathology, type of surgical interventions, intensity, frequency and duration of headache as well as shorter postoperative monitoring of patients. The location, degree and extent of mucus contact are often key in the range between good and bad results. Sometimes small surgical interventions will give excellent results, and in other cases, much greater intervention to achieve adequate extension of nasal canals and elimination of mucous contacts will remain without a satisfactory result. This suggests that the pathophysiology of pain in this type of headache has not been fully clarified and that further testing should be directed to the molecular level [14-16].

A less invasive option in the treatment of a headache of the contact point involves the use of neural blockages. Usually a local anesthetic in the form of lidocaine or xylocain is combined with corticosteroids and is applied approximately 5 mm above the center of the central nose in the mucous membrane of the nasal side wall. The results were variable, but more than 50% of patients experienced significant relief after the second dose [17]. In our statistics in over 55% of cases, patients were satisfied with this treatment.

Conclusion

Contact point headache is still a diagnostic-therapeutic problem. This is indicated by over 20% of dissatisfied patients who do not have a single form of treatment did not help. Surgical removal of the contact points of the nasal mucosa through various endonazal procedures reduces the intensity of the headache. In our causality, 73.3% of the cases resulted in cessation or a significant pain resolution. This indicates that surgery is a satisfactory option in the treatment of this pathology. Conservative treatment in the form of anterior etmoidal nerve blockade resulted in a poorer result, and the headache was significantly reduced or completely disappeared in 55.5% of treated patients. The author believes that, when a headache is suspected before contact surgery, the patient must go through a complex diagnostic procedure to exclude other causes of headache. In addition, more precise criteria for selection of patients planned for surgery or other types of treatment should be developed, which should improve overall results. Studies with a longer period of time should be designed in the role of different locations of contact points in predicting the success rate.

References

- Patel ZM, Kennedy DW, Setzen M, Poetker DM, DelGaudio JM (2013) "Sinus headache”: rhinogenic headache or migraine? An evidence- based guide to diagnosis and treatment. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol 3(3): 221-230.

- Kari E, DelGaudio JM (2008) Treatment of sinus headache as migraine: the diagnostic utility of triptans. Laryngoscope 118(12): 2235-2239.

- Patel ZM, Setzen M, Poetker DM, DelGaudio JM (2014) Evaluation and management of "sinus headache” in the otolaryngology practice. Otolaryngol Clin North Am 47(2): 269-287.

- Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD (2014) Headaches caused by nasal and paranasal sinus disease. Neurol Clin 32(2): 507-523.

- Roozbahany NA, Nasri S (2013) Nasal and paranasal sinus anatomical variations in patients with rhinogenic contact point headache. Auris Nasus Larynx 40(2): 177-183.

- Stammberger H, Wolf G (1988) Headaches and sinus disease: the endoscopic approach. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol Suppl 134: 3-23.

- Huang HH, Lee TJ, Huang CC, Chang PH, Huang SF (2008) Nonsinusitis-related rhinogenous headache: a ten-year experience. Am J Otolaryngol 29(5): 326-332.

- Parsons DS, Batra PS (1998) Functional endoscopic sinus surgical outcomes for contact point headaches. Laryngoscope 108(5): 696702.

- Herzallah IR, Hamed MA, Salem SM, Suurna MV (2015) mucosal contact points and paranasal sinus pneumatization: Does radiology predict headache causality? Laryngoscope 125(9): 2021-2026.

- Aleksandar Peric, Dejan Rasic, Ugljesa Grgurevic (2016) Surgical Treatment of Rhinogenic Contact Point Headache: An Experience from a Tertiary Care Hospital. Int Arch Otorhinolaryngol 20(2): 166-171.

- Peric A, Sotirovic J, Baletic N, Kozomara R, Bijelic D, et al. (2008) Concha bullosa and the nasal middle meatus obstructive syndrome. Vojnosanit Pregl 65(3): 255-258.

- Sadeghi M, Saedi B, Ghaderi Y (2013) Endoscopic management of contact point headache in patients resistant to medical treatment. Indian J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 65(2): 415-420.

- Welge-Luessen A, Hauser R, Schmid N, Kappos L, Probst R (2003) Endonasal surgery for contact point headaches: a 10-year longitudinal study. Laryngoscope 113(12): 2151-2156.

- Peric A, Baletic N, Sotirovic J (2010) A case of an uncommon anatomic variation of the middle turbinate associated with headache. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 30(3): 156-159.

- Clerico DM, Evan K, Montgomery L, Lanza DC, Grabo D (1997) Endoscopic sinonasal surgery in the management of primary headaches. Rhinology 35(3): 98-101.

- Mokbel KM, Abd Elfattah AM, Kamal S (2010) Nasal mucosal contact points with facial pain and/or headache: lidocaine can predict the result of localized endoscopic resection. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol 267(10): 1569-1572.

- Yarmohammadi ME, Ghasemi H, Pourfarzam S, Nadoushan MR, Majd SA (2012) Effect of turbinoplasty in concha bullosa induced rhinogenic headache, a randomized clinical trial. J Res Med Sci 17(3): 229-234.