- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

A Comprehensive Review: Dementia Management and Rehabilitation

Nigesh K1* and Saranya TS2

1Clinical Psychologist, Department of Psychology, University of Calicut, India

2Research Scholar, Department of Applied Psychology, Pondicherry University, India

Submission: August 09, 2017; Published: August 21, 2017

*Corresponding author: Nigesh K., Consultant Clinical Psychologist, Dept. of Psychology, University of Calicut, Kerala, India, Email: nigesh89@gmail.com;nigesh.kalorath@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Nigesh K, Saranya T. A Comprehensive Review: Dementia Management and Rehabilitation. Glob J Add & Rehab Med. 2017; 3(2): 555609. DOI: 10.19080/GJARM.2017.03.555609

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

Introduction

Dementia: The progressive syndrome of dementia is defined as a loss of memory plus impairment in at least one other cognitive function, such as aphasia, apraxia, agnosia and disturbance in executive function, which is severe enough to interfere with activities of daily living and represents a decline [DSM-IV, 1994].

Dementia presents with a variety of clinical manifestations regardless of aetiology, and in most cases it is caused by organic brain disease. It is characterized by three main symptomatic domains, as shown below.

a) Activities - inability to perform activities of daily life

b) Behaviours - psychiatric symptoms/behavioural disturbances

c) Cognition - neuropsychological impairments

Dementia is a general term for the loss of memory and other intellectual abilities serious enough to interfere with daily life. Dementia is not a disease or diagnosis, but rather a set of symptoms. Dementia is defined as a loss of mental abilities caused by damage to brain cells that is not part of the normal aging process. We all tend to degenerate after 40 years and it is a normal aging process, which is no way means that the person is having dementia. People with dementia appear confused and may have problems with their thinking that interferes with their social relationships at work, home and in community life. It is important to remember that there are many different types of dementia, and that dementia is caused by a variety of health problems. As a result, each person will have slightly different symptoms and behaviors.

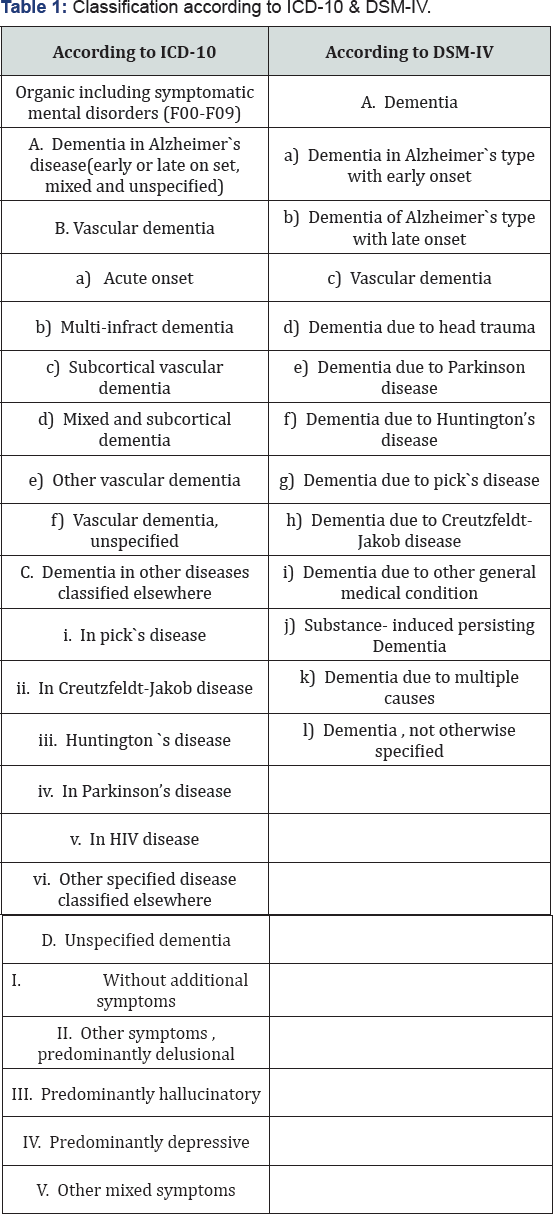

Classification of Dementia

Classification according to ICD-10 & DSM-IV (Table 1).

Epidemiology: In 2010, there are 3.7 million Indians with dementia and the total societal costs is about 14,700 crore. While the numbers are expected to double by 2030, costs would increase three times. Families are the main carers and they need support. (Alzheimer's and Related Disorders Society of India, New Delhi, 2010). 35.6 million People were estimated to be living with dementia in 2010. There are 7.7 million new cases of dementia each year, implying that there is a new case of dementia somewhere in the world every four seconds.

Getting older puts people more at risk for developing Alzheimer's disease and other dementias. As listed here, nearly half of the people over the age of 90 years have a functionally limiting dementia. The words "functionally limiting" are important. Over a period of time, the loss of ability caused by dementia interferes with the person's ability to do even simple day-to-day tasks. While many people are able to be cared for at home, many more will be moved to a supervised setting to assure their health and well-being

Dementia: Essential Features

The essential feature of a dementia is the development of multiple cognitive deficits that include memory impairment and at least one of the following cognitive disturbances: aphasia, apraxia, agnosia, or a disturbance in executive functioning. The cognitive deficits must be sufficiently severe to cause impairment in social or occupational functioning (e.g., going to school, working, shopping, dressing, bathing, handling finances, and other activities of daily living) and must represent a decline from a previously higher level of functioning.

Memory and Language Functions: Dementia involves a progressive loss of abilities. The most common lost ability is memory. Loss of short-term memory usually comes first, and long-term memory is lost later in the disease. That means the person may be able to tell you about their past history in great detail but can't remember what they had for breakfast. Over a period of time, the person will also lose their ability to use language. This is called "aphasia" which is also common among people with strokes. Early in the dementia, the person may have trouble finding words, but over the course of the disease will become less and less able to understand what is said to them, or express their needs or thoughts. Most people eventually become mute in the advanced stages.

Sensory and Motor Functions: Another loss that is commonly caused by dementia is the loss of purposeful movement, which is called APRAXIA. Even though the person is mobile, and has no physical problems to explain their inabilities, they can’t do even "simple" tasks. Commonly performed movements like dressing, grooming, or even buttoning, are "lost." Some people also lose their ability to accurately interpret what is going on around them - called AGNOSIA. Even though their sight and hearing and other senses all work reasonably well, they are not able to "use" this sensory information. They don’t seem to understand what they appear to see or hear. AGNOSIA causes similar, and yet different, types of problems as sensory impairment.

In sensory impairment, the person can’t hear or see well enough to understand what is said or done - they MIS-interpret information. In agnosia, the person’s inability to recognize common objects can't be explained by sensory impairment. They see or hear what is said or done - but cannot accurately interpret it. And often, the person with dementia has both problems, agnosia AND sensory impairment. As you can well imagine, these lost abilities show up in some behaviors that are sometimes hard for caregivers to understand.

Executive Functioning: The person with progressive dementia has difficulty thinking abstractly, which is the ability to "think about thinking." They aren’t able to reason, which requires being able to think about several things at once. Their ability to problem-solve, which requires making a choice after considering different options, is lost. Judgment, which is the ability to make a choice based on values and beliefs, is also lost. The person may say or do things that seem "inappropriate" to the situation or setting, things they would not do otherwise. Cursing and name calling are common problems associated with impaired judgment.

Loss of to control impulses also deteriorates in dementia. The person is unable to "hang on for a minute." If their instinct (impulse) is to say or do something, they likely will. Again, these losses combine and overlap to create changes in personality, emotion, and behavior. In many ways, the person is "not him or herself" anymore. This causes lots of pain and sadness to family, who may say things like "My mother would never say or do such a thing. This isn't her."

Personality, Emotion & Behaviour: Again, these losses combine and overlap to create changes in personality, emotion, and behavior. In many ways, the person is "not him or herself" anymore. This causes lots of pain and sadness to family, who may say things like "My mother would never say or do such a thing. This isn’t her."

a. Catastrophic Behaviors: Another group of behavioral symptoms are called CATASTROPHIC REACTIONS or catastrophic behaviors. Which are unexpected, intense, seemingly "out of nowhere" and out of proportion reactions to a situation? These behaviors may include anger, aggression, tearfulness, withdrawal, and other behaviors and emotions listed on this slide. Even though the behavior SEEMS to "come out of nowhere," often there is a reason. If caregivers take time to carefully think about the events that preceded the behavior, many times a cause can be found.

A number of clinical manifestations / problematic behaviors result from the loss of ability caused by Alzheimer's disease or any other cause of dementia. The loss of memory, judgement, impulse control, ability to reason, abstract thinking and use of language, decreased motor ability or loss of muscle movement (Akinesia) can cause the person to do some pretty distressing things and it will markedly affect his/her activities of daily living.

b. Common behavioral Symptoms: are concealed memory losses, wandering, sleep disturbances, losing and hiding things and mood or affective disturbances like pt. May show shallow affect (Flat facial expression or lack of emotional expression), loss of insight into personal and social misconduct such as inappropriate sexual behaviours etc. As a result, a wide variety of behaviors may be observed. The following are some of the more common types of behavior:

I. Concealed memory losses: "covers up" what they don't know; seems to be better off than they really are

II. Wandering: goes into other resident's room, causing anger and resentment; risk of injury or getting lost if goes outside

III. Sleep disturbance: wakes others

IV. Losing and hiding things: accuses others of stealing; families express frustration and concern

V. Inappropriate sexual behaviors: upsetting to staff and residents

VI. Repeating questions: monotonous repetition due to memory loss

VII. Repetitious actions: clapping, rocking, pulling, hair, rubbing

VIII. Territoriality: protective of own space; e.g., pushes others away at the dining table

IX. Hallucinations: seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting, or feeling things that are not really there; hearing things is the most common type

X. Delusions: false beliefs that are maintained (fixed) in spite of clear and obvious proof

XI. Illusions: misinterpretation of something real in the environment (e.g., hears water dripping and thinks someone is knocking on the door)

Causes of Behavioral Problems

A. Biological: due to the disease process itself

B. Psychological: loss of function and autonomy, attempts to maintain some control, denial of deficits, etc.

C. Social: family distress, economic issues, family conflicts over care.

D. Environmental: increased sensitivity to changes, issues of safety, etc.

Dementia can be caused by many different factors. Many times it is caused by specific disease such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson's. Other times it may be caused by treatable physical conditions such as infection or dehydration. It is important to see a doctor and to assess treatable causes of dementia symptoms such as depression, vitamin deficiency, and infections such as UTI (urinary tract infection). These other conditions can cause cognitive confusion. Symptoms may improve when the underlying cause is treated. While Alzheimer's disease accounts for 50-70% of cases of dementia, there are a number of other disorders which produce dementia symptoms.

The onset of AD is often steady and gradual. The symptoms get worse over time, which is why we call it a "progressive" dementia. The person with AD gradually becomes more and more disabled; that means they'll be less and less able to get along on their own, and will need assistance with even simple day-today tasks. The loss of abilities in AD occurs over a period of months to years - from 2 to 20 years with an average of 10 years from the early stages until death. Losses in AD are often grouped into stages to help us think about "where the person is" in the disease process. However, the course of dementia, both in terms of the symptoms the person has and how long the illness lasts, is varied and unpredictable.

Vascular dementia, results from impairment caused by reduced blood flow to parts of the brain. It is often considered the second most common type and symptoms can be similar to Alzheimer's.

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is most common clinical syndrome associated with Frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD). It associated with a non-Alzheimer’s pathology that primary affects the frontal and temporal cortex. Alterations in personality and behaviours are the most salient clinical features of FTD. Dementia can also caused by other neurological diseases like Parkinson's or Huntington's disease.

Parkinson's affects control of movement, resulting in tremors, stiffness and impaired speech. Many people with Parkinson’s also develop dementia in later stages of the disease. There are other causes, though rare: Lewy bodies - often starts with variations in attention and alertness and individuals often experience visual hallucinations and tremors; Dementia may be "due to" Medical illness like HIV disease, or Other rare diseases like Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease and Pick's disease. Pick’s disease may be hard to distinguish from Alzheimer's. Personality changes and disorientation often occur before memory loss. Dementia many also be caused by head trauma. In this situation, the dementia is stable and does not progressively get worse. Dementia can also be caused by substance abuse that persists even when the substance use stops. Of importance, two additional types of dementia are increasingly recognized by researchers, but are not yet in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, 4th Edition (DSM- IV) of the American Psychiatric Association:

a) Diffuse Lewy Body Disease, and

b) Frontal Lobe Dementia

Like other types of dementia, each one has unique signs and symptoms that make them somewhat different from others.

Finally, it is really important to know that a number of medical conditions can cause dementia. Of interest, a number of these medical problems are "reversible" if treated right away. For example, lack of oxygen can cause temporary confusion, but if not treated, can cause permanent damage (e.g., anoxic damage). Likewise, untreated vitamin deficiency, or other untreated health problems that cause acute confusion (also known as DELIRIUM) can cause permanent damage (e.g., DEMENTIA) if not treated.

There are lots of differences

a) Within certain types of dementia (e.g. Alzheimer’s disease)

b) Between types (e.g., frontal lobe dementia and Alzheimer's)

Overlapping syndromes are common. A person can have

I. Dementia (causing chronic confusion) AND delirium (causing acute confusion)

II. Alzheimer’s disease AND vascular dementia.

In summary, variability - or differences between people - is far more common that most people expect. As a result, care must be individualized and person-centered.

"Reversible” Dementia

As noted earlier, medical problems and health conditions can cause confusion and other behaviors that "look like" dementia - but are NOT. If left untreated, some of these will eventually cause permanent brain damage, which is then considered "dementia." Of most importance, the person with dementia can have an overlapping health problem that causes their confusion to be WORSE. Even when you know the person has Alzheimer's disease or some related disorder, always be alert to RAPID loss of ability, increased confusion, or change in function. Many times, this signals another health problem that can be treated. Although the person never recovers the abilities lost DUE TO DEMENTIA,they may get "better" because the health problem was treated. The confusion, or loss of function caused by the health problem, goes away. A number of health problems are known to cause symptoms that may look like Alzheimer’s disease. This memory aid, which spells "dementia," can help you remember some of the more common causes.

D-Drugs: antipsychotics, antihypertensive, anticholinergic, diuretics, sedatives, hypnotics

E-Emotional disorders: depression, paranoid schizophrenia

M-Metabolic disorders: hypoxemia, myxedema, hypoglycemia, electrolyte disturbances

E-Endocine (Ears and Eyes): impaired vision and hearing

N-Nutritional deficiencies: B12, folate, thiamine, anemia due to iron deficiency

T-Tumors and Traumas: brain cancer, accidental injuries (not reversible)

I-Infections: urinary tract, respiratory, pneumonia

A-Alcoholism

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

Interventions

Focus of Dementia Management

a) Alleviate patient’s distress

b) Reduce care-giver burden

c) Delay institutionalization

d) Assure safety

e) Patient's often become 'more like themselves'

Management of Behavioural and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia involves a combination of:

a) Support and information for the carer

b) Assessment of environmental triggers

c) Exclusion of underlying medical causes (i.e. Pain, infection) and, finally,

d) The judicious use of medications in some cases

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

General Principles of Managing Dementia

The principles take into account impairment of individual’s ability to learn.

A. Acceptance: The first principle in managing persons with cognitive impairment is accepting their present level of functioning: learning to value what is still there, and not dwelling on functions they have lost. It is often necessary to tell those individuals who are heavily dependent on the affected person directly that their loved one can no longer be left alone or to maintain nutrition independently.

B. Non-Confrontation: This is important in dealing with persons who are unaware of their deficits. A non confrontational approach requires caregivers to note the abilities and disabilities of cognitively impaired person and then to fill in or compensate for those disabilities [1-4].

C. Optimal Autonomy: To a greater or lesser extent, all persons values their ability to govern themselves and their environment. The task in dealing with cognitively impaired persons is helping them to find and operate at the level of autonomy most consistent with their personal needs and coping abilities.

D. Simplification: It refers to reducing the number and complexity of their environment demands 45 and introducing tasks in simple steps rather than as a set of serial or contingent ("if this and this happens do such and such things") instruction. It is especially helpful with a person who has difficulty dressing and undressing [4,5].

E. Structuring: Cognitively impaired persons are limited in their ability to provide structure for themselves, and structuring daily activities and the environment often becomes the responsibility of caregivers. Bourgeois et al. have used 3×5 inch index cards containing the person's schedule for the day as a means to reduce repetitive questioning. Sameness means having meals at roughly the same time each day, going to bed at the same time each day, and going to walk or engaging in other activities at the same time daily.

F. Multiple Cueing It refers to using several different types of stimulus to initiate and maintain a suggested action or activity. Non verbal cues are more useful than the verbal cues.

G. Repetition: It is necessary because of attention deficit and slowness of information processing. If attempting person in a new activity, the person’s attention must be first engaged, usually by calling his or her name. The verbal repetition may be underscored by an additional cue of placing a hand on the person’s arm and entering the field of vision.

H. Reinforcement: It involves the process of encouraging positive behavior.

I. Reducing Choices: Advanced cognitive impairment makes choosing difficult, it is no longer possible to easily weigh the relative value of multiple alternatives.

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

General Treatment Strategies

There is no single test that proves a person has Alzheimer's but a skilled physician can diagnose Alzheimer’s with more than 90% accuracy with a full diagnostic workup. A comprehensive evaluation would include gathering a history of symptoms from the affected person's perspective but also the family's perspective; reviewing the medical history including medications and ruling out medication interactions that may be contributing to the symptoms; evaluating mood and status; and conducting a physical exam to rule out other disorders. Neuropsychological testing (pen, paper and verbal cognitive testing) may also be recommended. In many cases a primary care doctor may refer a patient to a specialist - such as neurologist, Psychiatrist, or Psychologist [6-10].

A. Prevention

a) Identify risks and mitigate

b) Develop Neuroprotective strategies for those at risk

c) Dietary supplements- Several nutrient deficiencies are known to be risk Factors for AD. Evidence suggests that consumption of fish with high fat content and marine omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid decreases the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia.

B. Slow down/ halt the progression of illness:

a) Understanding pathophysiology leads to treatment ideas

b) Treating with

i. Calcium channel modulation and excitatotoxic systems attenuation (such as memantine)

ii. Anti-inflammatory/immunosuppressive strategies (e.g. Nsaids)

iii. Gene therapy for defective protein regulation

iv. Toxin removal (Desferroxamine, clioquinol) / Ventriculoperitoneal shunting (cognishunt)

v. Amyloid Protein strategies

vi. Other Neuroprotective strategies

c) 5 years delay in onset--> 1/3 decrease in prevalence

d) Helps to delaying institutionalization

C. Reverse symptoms

a) Medication, at times treating the underlying disease conditions of reversible causes of dementia.

b) Compensate through augmentation of remaining neurons or other systems

c) Reversal of destructive processes & regeneration of tissue.

D. Management of Psychological Symptoms: Both Pharmacological and non- pharmacological interventions are mandatory, but should avoid the unnecessary medication. Only give medication, when problems are clinically indicated [11-14].

E. Caregiver Support and Education: Educate the caregiver and acknowledge care giver burden

F. Management Planning: Over the last three decades, interest has grown in the use of psychosocial interventions for people with dementia. Empirical studies and systematic reviews have been undertaken on a range of such interventions to examine their effectiveness. However, little account has been taken of the appropriateness of psychosocial interventions for people in different stages of the illness. Before judging the management, it is helpful to assess the patient's current condition which will help in formulating the target behavior. The common points in assessment includes-

i. Cognitive functions- the focus should be on to find out the areas of preserved function, or to say those areas having lesser degree of impairment, that is helpful in management to identify the person’s style of coping.

ii. Life story- what are the preferences or choices.

iii. Social network- it includes resources available like caregivers, and other support and what are the relationships among them.

iv. Person’s behaviour causing distress- what actually the person is doing, when and under what circumstances.

v. Why patient is behaving in this manner?

vi. What realistically can be changed?

G. Psychosocial Management: Psychosocial Management involves rehabilitation interventions which help us to manage behavior, perceptions and reactions to your injury or condition which may hold back the process of recovery or maintenance of your wellbeing [9]. A rehabilitation program may focus solely on a package of psychosocial interventions. However, it is more likely that psychosocial activities will be offered in conjunction with medical and or vocational rehabilitation services.

a. Purpose of Psychosocial Management: Its purpose is to change patient's perceptions of injury, pain, future loss and life changes which can undermine recovery and wellbeing. Its aim to help alleviate anxiety associated with accepting an injury and the recovery process and assist in maintaining or improving wellbeing. Psychosocial interventions help address issues which can undermine and act as barriers to progressing rehabilitation.

Psychiatric management, also known as psychosocial management, and usually simplified to psych rehab, is the process of restoration of community functioning and well-being of an individual who has a psychiatric disability. The Board of Directors of the United States Psychiatric Rehabilitation Association (USPRA) approved and adopted the following standard definition of psychiatric rehabilitation: Psychiatric management promotes recovery, full community integration and improved quality of life for persons who have been diagnosed with any mental health condition that seriously impairs their ability to lead meaningful lives.

The goal of psychosocial management is to help disabled individuals to develop the emotional, social and intellectual skills needed to live, learn and work in the community with the least amount of professional support. The overall philosophy of psychiatric management comprises two intervention strategies. The first strategy is individual-centered and aims at developing the patient’s skills in interacting with a stressful environment. The second strategy is ecological and directed towards developing environmental resources to reduce potential stressors. Most disabled persons need a combination of both approaches. The refinement of psychiatric rehabilitation has achieved a point where it should be made readily available for every disabled person [15,16].

b. Types of psychosocial assistance: Psychiatric rehabilitation services are collaborative, person directed and individualized. These services are an essential element of the health care and human services spectrum, and should be evidence-based. They focus on helping individuals develop skills and access resources needed to increase their capacity to be successful and satisfied in the living, working, learning, and social environments of their choice. Psychosocial interventions, recommended by a rehabilitation service provider may include measures such as:

I. General psychosocial counselling, adjustment / family/ relationship counselling, parenting support, anger management,

II. Basic life skills (re)training,

III. Involvement in community support services, self-help or chronic disease/illness support groups

IV. Health/fitness and exercise regimes,

V. Drug and alcohol management programs,

VI. Lifestyle programs,

VII. Financial counselling

VIII. Attendant care, home support and accessing accommodation service

c. Behavioural management of dementia approaches: It is used for the intervention in the management of challenging behaviors in a dementia Patient. Emerson has pointed out certain challenging behaviors that these patients exhibit

i. Repetitive screaming

ii. Scratching self

iii. Outburst of temper

iv. Hitting own head by hand or by object.

v. Biting self or others.

Now from a behavioral perspective, what the person actually does is an interaction between his skills and abilities and environmental influences. Thus changing the person’s behavior can be achieved either by changing the person’s environment or by teaching him new skills through Reinforcement or by combination of both. In dementia, the emphasis must be on changing the environment, as the nature of dementia makes skill learning difficult. However, this is not to say that they cannot learn new skills, they can indeed learn but it is documented that this ability to learn should be kept for those areas of functions, where the patient will benefit most from new learning. In real life the concept of reinforcement can be best used for this. Reinforcement can be provided in terms of patting the back or talking to him for sometime etc. For this we should keep these things in mind [17-20]-

a. What are the conditions/settings in which the behavior typically occurs?

b. Is it affected by some environmental factors (e.g. Noise, people, light etc?)

Literature review suggests that wandering behavior and some stereotyped behaviors can successfully be reduced using this technique.

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

Cognitive Strategies

It can be used to reduce the cognitive load on the patient with dementia. A point of caution is that it should be used taking into account the status of cognitive functioning. In reducing cognitive overload, spoken words may be supplemented with relevant pictures and objects to provide a context for what is said which helps in increasing social interaction of these patients. Other measures include using short simple sentences during conversation and giving instructions by the family members/staff. This reduces the distraction. External memory aids could also be used to reduce the load on memory. This includes use of cues, prompts etc. But these cues have to be obvious/ salient in nature like picture of toilet on the sign board which is more effective than a symbolic figure. For e.g., a white board with important information is more effective than a plain diary, if it is placed at the right place (may be where the patient comes frequently). However, studies indicate that in some cases of dementia, one has to go a step further. This means that one should make them learn the association between cue and its meaning. For example: Sound of bell= go to toilet [21].

Then ask, what sound of bell meant to you. Based on this, a model has been proposed called "Model of cue recall behavior"- It involves:

i. Acquisition- patient is taught using spaced internal and fading cues, the association between cue and the information. It is meant to prompt e.g. Cat picture on door= my room.

ii. Retrieval- whenever cue is encountered in the environment, information is recalled.

iii. Maintenance- because of the retrieval affect, whenever recall is correct, it tends to maintain the association. It should be used sensibly; only one association is taught at a time, and only few in number. Teri & Gallagher- Thompson have reported positive findings with people in the early stages of Alzheimer's disease. Individual and group cognitive therapy has also been used by other researchers with some favourable results [22].

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

Reality Orientation Therapy

It is most widely used. It is made of two parts:

a) Verbal orientation: It is the ability to answer question relating to time, place, and person orientation.

b) Behavioural orientation: It is the ability to find the way from place to place without getting lost [4,16].

In management, generally two aspects are targeted which are 24 hour reality orientation (RO) and reality orientation in group sessions 24 hour reality orientation is a continuous process. It is totally carried out by using clocks, calendar (for day, month, and year), and Direction board (for going to a certain place). In 24 hour RO, the environment is manipulated with a clear sign post around Home/Ward, notices are placed at appropriate places and the staff may also be trained to give consent orientation, but only when desired by the patient. In RO group session, the patient meets with staff members for 30 minutes bi-weekly and discusses about current events. Studies 7 have pointed out that this increases the efficacy of 24 hour reality orientation. Studies 14, 15 have also shown that there is evidence that reality orientation is an effective intervention in improving cognitive ability, as measured using the MMSE [23-26].

Furthermore, as Baldelli and colleagues’14 follow-up data shows, the improvement in cognitive ability, even taking into account a decline after the end of the intervention period, is maintained 3 months after the collection of post-test data. However, neither study demonstrated that reality orientation is effective in improving well-being. Finally, no evidence was found that reality orientation is effective in improving communication, functional performance, and cognitive ability measured in terms of memory recall. Despite these concerns, the debate concerning efficacy has been largely settled following Spector et al.’s [26] favourable review of the six randomized controlled trials of this therapy.

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

Formal Psychotherapy

Psychotherapy may be useful in earlier stages of dementia before short-term memory is too impaired. Several forms of therapy have been studied in dementia; the most promising are reminiscence therapy and supportive psychotherapy. Reminiscence therapy allows patients to recall and relive past life events, stimulating memory and mood within the context of their life history. This therapy has resulted in modest short-term gains in mood, behavior, and cognition in "confused" elderly persons. The focus of supportive psychotherapy in the early stages of dementia is adjusting to the illness and losses inherent with it. There is little evidence supporting its efficacy. Supportive psychotherapy is a rather neglected aspect of psychotherapy, but we believe that it is a particularly useful strategy that can play an important role in positively influencing the quality of life in those affected by dementia.

Bloch in his Introduction to the Psychotherapies (1979; now in its fourth edition) describes supportive psychotherapy as a form of psychological treatment given to people with chronic and disabling psychiatric conditions for whom fundamental change is not a realistic goal. This, of course, suggests that supportive therapy is one of the most commonly practised types of psychotherapy. It is a form of treatment in which therapist support is a core component. Gilbert & Ugelstad (1994) [2730] believe that the therapist’s primary role in supportive psychotherapy is to support and strengthen the individual’s potential for better and more mature ego functioning in both adaptation and developmental tasks. 'Superficial psychotherapy' that uses techniques such as inspiration, reassurance, suggestion, persuasion, counselling and re-education with people who are too psychologically fragile, inflexible or defensive for exploratory therapies.

Behavioral Management

Given the prevalence of behavioral disturbances in dementia, behavioral management has an important role in the management of dementia-related behavior problems. Behavioral treatments that identify antecedents and consequences of problem behaviors and then effect changes in the environment to alter the behaviors have been shown to be beneficial in reducing disruptive behaviors only in small trials and case studies but are widely employed in clinical practice [30-35]. For example, scheduled toileting can reduce the frequency of urinary incontinence. Behavior management training programs for caregivers in the community or in residential or nursing homes have shown modest reductions in problem behaviors and, in some studies, improvement in mood, cognition, and physical role function. Limited follow-up data suggest that the benefits do not persist beyond the intervention.

Over the past 10 years- increasing interest in applying therapeutic frameworks, such as Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, Cognitive Stimulation Therapy and Interpersonal Therapy for dementia patients. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy is appropriate for people with dementia: Many of behavioural difficulties encountered emerge through one or more of the cognitive features such as Cognitive misinterpretations, Biases, Distortions, Erroneous Problem solving strategies, and communication difficulties. Teri and Gallagher-Thompson- reported positive findings from a clinical trial of CBT with Early stage of Alzheimer’s disease. Individual and Group CBT has shown favorable results.

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

Validation Therapy

It was developed by Naomi Feil19 in 1960s’ in USA. Originally called as fantasy therapy, it is based on the fact that some of the features associated with dementia were active strategies on the part of the patient to avoid stress, boredom, loneliness etc, as the reality is often too painful for the patient, and he retreats into inner reality (fantasy). In this therapy the therapist just validates the feeling of the patient and then gradually helping him to move from his inner world to the shared reality of the surrounding. It includes the use of empathy, empathic communication, reminiscence and touch to establish emotional contact with cognitively impaired persons. Hitch noted that validation therapy promotes contentment, results in less negative affect and behavioural disturbance, produces positive effects and provides the individual with insight into external reality. However Neal & Briggs felt that one still had to be convinced with respect to its efficacy [30].

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

Reminiscence Therapy

It includes helping the patient to think about and review positive past experiences, eg., Birthday, family holidays etc. The aim is to provide pleasure and cognitive stimulation by focusing on happy memories. Although Spector et al. [34] concluded that there was little evidence of a significant impact of the approach other studies indicate that this may lead to improvement in certain behavior like self care.

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

Life Review Therapy

It is concerned with correction of negative memories. According to Buechal it is a process of re-evaluation, resolution and reintegration of past conflicts, giving new significance to one's life.

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

Activity Therapy

It emphasizes on activity instead of self-observation and verbally mediated learning. Patient’s attention is drawn away from themselves and towards the accomplishment of pleasurable or useful tasks.

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

Memory rehabilitation programme basically focusing on teaching the use of external memory aids to compensate for memory impairment is perhaps, one of the most important approaches in memory rehabilitation. The MRP is a specialist Occupational Therapist-led six-week customised programmes which take place in the patient’s own home with designated caregiver, where possible. The MRP aims to teach the patient to compensate for their memory deficits and includes minor adaptations to the home environment to support these strategies.

List of compensation strategies commonly used in the Memory Rehabilitation Programme

a) Customised medication checklist

b) Memory book--(put things where you keep things)

c) Memory board--(split white/cork board)

d) Printed customised Daily Schedule

e) Printed customized safety checklist--(safe night time routines)

f) Alarm clock

g) Calendar

h) Telephone message prompt card by phone --(write down all messages, tell the caller that you are writing down, read message back to the caller)

i) Pocket notebook

Recent advancements in assessment and intervention of dementia:

a. Telephone screening test for dementia has been published. (A.L camozzato et.al., 2011.Brazil. Aging, Neuropsychology and Cognition.18:180-194). Comparison with comprehensive assessment, including neuropsychological testing. Comparison between Normal in-person MMSE and Braztel MMSE (phone version) showed significant correlation. Studies showing significant evidences for the effectiveness of internet based cognitive rehabilitation in person with memory impairments.

b. Varieties of Home-Based Rehabilitation

i. Patient carries out rehab at home without any input or support

ii. Patient carried out rehab at home with input and support from carer

iii. Patient carried out rehab at home with remote guidance and support from professional

iv. Patient carried out rehab at home with weekly visits, guidance and support from professional

v. (Training of carers, if available, needs to be integral part of home-based rehab, especially for those with limited insight/motivation, and who have major needs)

Other Modalities- Are

a. Multisensory stimulation and combined therapies: It has been suggested that because dementia often results in an alteration of several sensory modalities, less is to be gained by an intervention designed to deal with a single sense than can be gained through multisensory stimulation. This approach uses a variety of equipment such as lighting effects, relaxing music, recorded sounds, massage cushions, tactile surfaces and fragrances to create a multisensory environment.

b. Aromatherapy: "Aromatherapy can be defined as the controlled use of essential oils to maintain and promote physical, psychological, and spiritual wellbeing." Gabriel Mojay. As a holistic practice, Aromatherapy is both a preventative approach as well as an active method to employ during acute and chronic stages of illness or 'dis'-ease. Aromatherapy with essential balm oil is a safe treatment which appears to be efficacious for the treatment of clinically significant agitation in people with severe dementia, with additional benefits for key quality of life parameters. The use of aromatherapy to reduce associated symptoms in people with dementia should be discussed with a qualified aroma therapist who can advise on contraindications.

c. Light Therapy: Sleep disturbance in people with dementia can be particularly distressing for carers. Biological changes in the brain can disrupt the normal circadian rhythm and sleep/ wake cycle. Bright light affects the production of melatonin, which may lessen these problems. Bright light therapy is a labour intensive intervention and there are problems in controlling the studies for staff interaction and in maintaining blinding.

d. Music Therapy: Evidence from a series of small under powered studies suggests that exposure to music, tailored to the individual's taste, can relieve agitation but not aggressive behaviour in people with dementia. It is not possible to determine whether the beneficial effect seen is the result of music therapy itself or other factors, such as the presence of the researcher. Music therapy is easy to implement, but more research is needed to determine whether it is beneficial to the person with dementia.

e. Multisensory Stimulation: Individuals exposed to multisensory environments showed less confusion and talked more spontaneously and in normal length sentences. In people with moderate dementia there was a small improvement in mood, apathy and restlessness for the duration of the session. For people with moderate dementia who can tolerate it, multisensory stimulation may be a clinically useful intervention. Multisensory stimulation is not recommended for relief of neuropsychiatric symptoms in people with moderate to severe dementia.

f. Physical Activities: Exercise may benefit the person with dementia by improving both symptoms and quality of life. It is thought that physically active people have a 'cognitive reserve' that is used when other areas of the brain are damaged. An exercise routine may decrease the severity of symptoms of dementia as well as lead to increased mobility and independence. An exercise routine for the elderly should be composed of four components:

i. Aerobic exercise

ii. Strength training

iii. Balance training

iv. Flexibility exercises

g. Recreational activities: Recreational activities should be introduced to people with dementia to enhance quality of life and well-being. Recreational activities give an opportunity for people with dementia to engage in meaningful activity and are often used as a way of facilitating the individual's need for communication, self esteem, sense of identity and productivity. Activities used range from self expression through drawing, music, arts and crafts, to cooking, games and interacting with pets.

h. Simulated Presence: Simulated presence therapy attempts to keep the environment of a patient with dementia as familiar as possible to reduce anxiety and distress. It involves making a recording of a familiar person and playing it to the patient. The recorded voice is usually reassuring but the content can be varied depending upon the interests of the individual patient concerned.

Social interventions

Social treatments involve changing the environment of the person and helping those who are principally involved in the care. Good reviews of these treatment strategies are provided by, Morris & Morris [21], Bradshaw [10], Levin [11] and Moore & Buckland [20].

Restructuring the environment

This looks at how the environment can be: made more safe; altered to enable the person to cope better; and be pleasant and stimulating. Measures which should be considered when planning an environment for people with dementia include:

I. Incorporating small size units

II. Separating non-cognitively impaired residents from people with dementia

III. Offering respite care as a complement to home care

IV. Relocating residents, when necessary, in intact units rather than individually

V. Incorporating non-institutional design throughout the facility and in dining rooms In particular

VI. Moderating levels of stimulation

VII. Incorporating higher light levels

VIII. Using covers over fire exit bars and door knobs to reduce unwanted exiting

IX. Incorporating outdoor areas with therapeutic design features

X. Considering making toilets more visible to potentially reduce incontinence eliminating factors that increase stress when bathing.

A patient’s safety needs to be kept under regular review, particularly in the light of increasing impairment. Maintaining a balance between safety and the restriction of a patient's freedom is one of the most difficult aspects of caring for people with dementia.

Safety

Ways in which people with dementia can come to harm:

a) Falling on slippery floors

b) Falling down stairs

c) Falling from bed onto hard floor or against furniture

d) Starting fire with matches, candles or cooker

e) Scalding with hot tap water or kettle

f) Wandering away and spending night outside or hit by traffic

g) Choking

h) Unsuitable ingestion of medication

Coping better

The environment should be reviewed to help the patient cope with problems. Some simple examples of environmental manipulations are summarized: someone cannot get lost if they wander off [19], and floor designs in front of exit doorways, which are thought to decrease the chance of confused people leaving the ward [10].

Pleasant and stimulating

It is important to design an environment which is likely to be pleasant and stimulating. Care must be taken, however, to take the patients’ perspective. There is a danger that in trying to make the surroundings stimulating they become confusing. The Domus philosophy of residential care is one recent attempt to improve the quality of those in long-term residential care [12]. It suggests following points while dealing with dementia patients.

a) Clear labeling of toilet rooms

b) Maintain consistent furniture arrangement

c) Enable carers to develop one-to-one relationships with patient

d) Maintain adequate lighting in all areas used by patients

e) Use identification necklace for those who wander off and become lost

f) Remove inedible objects which patient attempts to eat. More sophisticated measures include radio-tagging devices to ensure

Other Aspects

a. Education: Providing education to patients and their families about dementia, its course and consequences, and treatment is important in helping them to plan for future disability. While anticipating the upcoming stages can be difficult, it affords patients the opportunity to make arrangements while they are still able to be involved in the decision-making process. There are many excellent resources, including books and community agencies, available to help guide families through the care giving process.

b. Driving: Driving safety is an important issue. Dementia patients are at greater risk for motor vehicle accidents. Patients should be advised to limit their driving in the mild stages or at the first signs of impaired driving ability or accidents and to stop driving when they are in the moderate stages of dementia. Referrals for driving evaluations are recommended to assess driving skills when in doubt, or to confirm to patients their limitations. Many states have mandatory reporting laws. Driving restrictions can be very difficult for patients to accept due to the loss of independence and dependency on others for transportation needs. Families often need to get involved to enforce these restrictions, removing keys or disabling or removing vehicles.

c. Legal and Financial Planning: Patients and their families should be encouraged to pursue legal planning such as living wills, power of attorney, and guardianship for when they no longer have the capacity to make decisions for themselves.

d. Maintaining Safety: Another important aspect of dementia management is maintaining safety in the community. Patients with dementia are at greater risk for accidents. Forgetting to turn off the stove while cooking can lead to fires. Forgetting to lock doors can increase risk for burglary or home invasions. Demented patients are more vulnerable to predatory scams through door-to-door, phone, or mail solicitation. Addressing threats to patients' safety is necessary to protect patients from inadvertently harming themselves or others.

e. Abuse and Neglect: Patients with dementia are at greater risk for elder abuse and neglect. The strains of care giving are a risk factor for caregivers to abuse those in their care. In addition, due to the demented patient's poor memory and inability to recall or solve problems, they may be less likely to report abuse or the veracity of their reports may be questioned. There are several instruments used to screen for elder mistreatment, but none has been widely accepted. In situations where abuse or neglect of the demented patient is suspected, further evaluation is indicated. Reporting is mandated in some states when elder mistreatment is suspected so that a complete investigation can be conducted and interventions performed when necessary.

f. End-of-life Issues: Dementia is a terminal illness. While patients often die of intercurrent illnesses before the end stage of dementia, many patients succumb in the end stage of dementia, often due to pneumonia or other infections. Complications of end-stage dementia include loss of appetite, inability to feed one self, and swallowing difficulties, making it difficult to ensure adequate nutrition. When dementia progresses to this stage, families will be faced with decisions regarding many life- prolonging interventions, including placement of feeding tubes and treatment of emergent infections. Ideally, these issues will have been addressed with the patient while in early illness stages, or via a pre-existing advance directive, so the patient's can be used to guide the decision-making process. Alternatively, involvement of hospice or palliative care services can be considered.

g. Focusing on Carers: Those intimately concerned with looking after people with dementia need two kinds of support: practical and emotional support.

Practical support

a. Financial: Many carers are not receiving all the financial support to which they are entitled. It is important to ensure that they are properly informed and helped with making financial claims.

b. Respite: Many carers want to continue to look after the person with dementia, but their ability to cope is undermined by the lack of any respite. Day care can allow carers to carry out necessary tasks, such as shopping. It may enable them to continue in paid work with both financial and social advantages, and it can give them some much needed time to enjoy themselves. 'Holiday admissions’ in which the person with dementia is admitted for residential or hospital care for several days at a time, are another way in which carers can be given time to recreate themselves. It is sometimes possible for a sitter to look after the patient for several hours, in their own home, either during the day or at night, in order to allow the principal carer some respite.

c. Tasks: Help with providing food (e.g. Meals on wheels), cleaning, washing and dressing (e.g. a home help) can also relieve some of the burden from the principal carer.

d. Education: The importance of education for the carer must not be underestimated [23]. This includes information about the disease, its prognosis and likely consequences. It may include training in carrying out a programme of behaviour modification and information about giving medication. It can include information about the various means of obtaining practical support.

Emotional support

It is important that the carer is also cared for. Opportunities are needed for carers to talk about the problems they are having, and about their feelings, including the negative feelings about the person with dementia. Carers' support groups as well as experienced counsellors (such as community psychiatric nurses) can be of great benefit. One carer, whose wife had Alzheimer's disease, writing about his own experience offered these pieces of advice: do not hide the disease from those around you; take care of yourself; enlist help in all areas; and take calculated risks. Professional carers such as nurses, residential home staff, doctors and social workers, also need support and care. A professional team needs to build into it a mechanism to enable such support to be given. Hospital based professionals can help the staff of residential homes to think about and to achieve their goals [8].

Special Psychosocial Programmes

a. Educational Interventions for Patients with Dementia and Caregivers: Short-term programs directed toward educating family caregivers about AD should be offered to improve caregiver satisfaction. Intensive long-term education and support services (when available) should be offered to caregivers of patients with AD to delay nursing home placement. Staff of long-term care facilities should receive education about AD to reduce the use of unnecessary antipsychotics.

b. Functional Performance: Behavior modification, scheduled toileting, and prompted voiding should be used to reduce urinary incontinence,. Graded assistance, practice, and positive reinforcement should be used to increase functional independence. Low lighting levels, music, and simulated nature sounds may improve eating behaviors for persons with dementia, and intensive multimodality group training may improve activities of daily living, but these approaches lack conclusive supporting evidence.

c. Problem Behaviors: Persons with dementia may experience decreased problem behaviors with interventions such as music, particularly during meals and bathing, walking, or other forms of light exercise. Although evidence is suggestive only, some patients may benefit from the following-

i. Simulated presence therapy such as the use of videotaped or audio taped family member.

ii. Massage

iii. Comprehensive psychosocial care programs

iv. Pet therapy

v. Commands issued at the patient's comprehension level

vi. Bright light, white noise

vii. Cognitive remediation

d. Care Environment Alterations: Although definitive evidence is lacking, the following environments may be considered for patients with dementia.

A. Special care units within long-term care facilities.

B. Homelike physical setting with small groups of patients, as opposed to traditional nursing homes.

C. Short-term, planned hospitalization of 1 to 3 weeks with or without blended inpatient and outpatient care.

D. Provision of exterior space, remodelling corridors to simulate natural or home settings, and changes in the bathing environment.

e. Interventions for Caregivers: The following interventions may benefit caregivers of persons with dementia and may delay long-term placement. :

A. Comprehensive, psycho-educational caregiver training

B. Support groups- Additional patient and caregiver benefits may be obtained by use of computer networks to provide education and support to care givers, telephone support programs, and adult day care for patients and other respite services.

f. Family intervention: Since family bears the burden of understanding and managing the patient’s person and property, it is therefore important to address the education and physical and emotional support of family caregivers, after making a diagnosis.

g. Education about illness: Caregivers often need and want to learn about the cognitive and behavioral effect of dementing illness, its anticipated course and various social and financial consequences of the illness. Different caregivers require different information depending upon the type of the dementia. Handouts and literature can be used for the purpose like - Alzheimer's early stages: First Step in Caring and Treatment.

i. Prognosis: It is a very important issue for families. Most families can tolerate being told that a disease is expected to progress but that the exact course cannot be predicted. They can be told that there may be long periods of no apparent decline. Families of patients with AIDS can be told that there may be significant remission of cognitive symptoms with treatment of underlying disease. In case of vascular dementia, family may be offered the hope that progression may be slowed by the use of aspirin or anti-platelet drugs, but they should also be told that dementia will progress and that plans should be made accordingly. In case of Alzheimer’s disease, they can be told that the disease will progress, that its rate of progression is uncertain. This disease may result in complete inability to communicate or to care for himself or herself.

ii. Family risk: Some dementias involve risk to family members. In the case of Huntington's dementia and Alzheimer’s disease, the risks are genetics. When counselling about infectious disorders such as Jacob disease or AIDS, the clinician indicates that these diseases can be communicated only from body fluid to body fluid, suggesting that appropriate precautions be taken.

iii. Other major issues: Like how supervision is to be arranged, dealing with denial and projection in the family, dealing with family stress etc.

iv. The multi-disciplinary team: The management of people with dementia requires many different tasks to be undertaken. It is not usually appropriate for one person to carry out all of these tasks and effective teamwork is vital. For management to be effective, good and frequent communication between the team members is needed.

Care Programme Approach

The Care Programme Approach requires that all patients accepted by specialist mental health services must have a key worker who is responsible for making sure that their health and social needs are fully assessed. The key worker is responsible for a care plan that is negotiated with the patient and their carers. Other patients will be followed up by the community team and require regular Care Programme Approach reviews.

a) Doctors: evaluation of concurrent illness; prescription of medication; facilitating provision of hospital and community services

b) Nurses: general care of in-patients and nursing home residents; carrying out behaviour modification regimes; education and counseling of relatives; coordination of community services

c) Clinical psychologists: initiating behaviour modification programmes, offering advice and support to staff in a caring role

d) Social workers: facilitating provision of local authority services such as residential care, respite care, home care; counseling of carers

e) Occupational therapists: design of environment; education of carers; identification of strengths and abilities of patient.

- Research Article

- Introduction

- Interventions

- General Principles of Managing Dementia

- General Treatment Strategies

- Cognitive Strategies

- Reality Orientation Therapy

- Formal Psychotherapy

- Validation Therapy

- Reminiscence Therapy

- Life Review Therapy

- Activity Therapy

- Memory Rehabilitation Programme (MRP)

- References

References

- American Psychiatric Association (1994) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-1V), 4th edn.

- American Psychiatric Association USA (2000) American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-1V TR), 4th edn.

- Birks J, Grimley Evans J, Iakovidou V, Tsolaki M, Holt FE (2009) Rivastigmine for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000(4).

- Bullock R, Touchon J, Bergman H, Gambina G, He Y, et al. (2005) Rivastigmine and donepezil treatment in moderate to moderately- severe Alzheimer's disease over a 2-year period. Curr Med Res Opin 21(8): 1317-1327.

- Burns A, Gauthier S, Perdomo C (2007) Efficacy and safety of donepezil over 3 years: an open-label, multicentre study in patients with Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 22(8): 806-812.

- Campbell N, Ayub A, Boustani MA, Fox C, Farlow M, et al. (2008) Impact of cholinesterase inhibitors on behavioral and psychological symptoms of Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 3(4): 719-728.

- Farkas M, Anthony W (2002) Psychiatric Rehabilitation, second edition. Centre for psychiatric Rehabilitation.

- Garland J (1991) Making Residential Care Feel Like Home: Enhancing Quality of Life for Older People. Bicester: Winslow Press.

- Hill J, Carper M (1985) Greenery: Group therapeutic approaches with the head injured. Cognitive Rehabilitation 3: 4-17.

- Hussian RA, Brown DC (1987) Use of two-dimensional grid patterns to limit hazardous ambulation in demented patients. Journal of Gerontology 42(5): 558-560.

- Levin E (1997) Carers-problems, strains and services. In Psychiatry in the Elderly (eds R. Jacoby & C. Oppenheimer), 2nd edn. Oxford: Oxford University Press 392-402.

- Lindesay J, Briggs K, Lawes M, Alastair MD, Joe H (1991) The Domus Philosophy: a comparative evaluation of residential care for the demented elderly. Geriatric Psychiatry 6(10): 727-736.

- Lipowski ZJ (1987) Delirium (acute confusional states). JAMA 258(13): 1789-1792.

- Lishman WA (2001) Organic Psychiatry, the psychological consequences of cerebral disorder. UK .

- Lishman WA (1997) Organic Psychiatry. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific.

- Loeser JD, Truk DC (2001) Multidisciplinary pain management. In (Eds.), Bonica's management of pain 2069-2079.

- Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Michaels M, Resnick NM (2000) Delirium is independently associated with poor functional recovery after hip fracture. Journal of American Geriatric Society 48(6): 618-624.

- Mc Neny R, Dise J (1990) Reality orientation therapy. In M. Rosenthal, M.R. Bond, ER Griffith & JD Miller (Eds.), Rehabilitation of the adult and child with traumatic brain injury (2nd Eds.) Philadelphia 366-273.

- Mcshane R, Wilkinson J, Hope T, (1994) Tracking patients who wander: ethics and technology. Lancet 343-1274.

- Moore S, Buckland A (1997) Nursing in old age psychiatry. In Psychiatry in the Elderly (eds R. Jacoby & C. Oppenheimer), 2nd edn, Oxford: Oxford University Press. 303-317.

- Morris RG, Morris LW (1993) Psychological aspects of caring for people with dementia: conceptual and methodological issues. In Ageing and Dementia: A Methodological Approach (ed. A Burns), London, UK 251274.

- N Ahuja (2011) A short textbook of Psychiatry, 7th edition Jaypee brothers medical publishers, 19-32.

- Pollitt PA (1994) The meaning of dementia to those involved as carers. In Dementia and Normal Ageing (eds FA Huppert, C Brayne, DW O'Connor) 257.

- Hansen RA, Gartlehner G, Webb AP, Morgan LC, Moore CG, et al. (2008) Efficacy and safety of donepezil, galantamine, and rivastigmine for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Clin Interv Aging 3(2): 211-225.

- Harry RD, Zakzanis KK (2005) A comparison of donepezil and galantamine in the treatment of cognitive symptoms of Alzheimer's disease: a meta-analysis. Hum Psychopharmacol 20(3): 183-187.

- Howard RJ, Juszczak E, Ballard CG, Peter Bentham, Richard G. Brown, et al. (2007) CALM-AD Trial Group. Donepezil for the treatment of agitation in Alzheimer's disease. N Engl J Med 357(14): 1382-1392.

- Jones RW, Soininen H, Hager K, Aarsland D, Passmore P, et al. (2004) A multinational, randomised, 12-week study comparing the effects of donepezil and galantamine in patients with mild to moderate Alzheimer's disease. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 19(1): 58-67.

- Kaufer DI, Cummings JL, Christine D, Bray T, Castellon S, et al. (1998) Assessing the impact of neuropsychiatric symptoms in Alzheimer's disease: the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Caregiver Distress Scale. J Am Geriatr Soc 46(2): 210-215.

- Maidment ID, Fox CG, Boustani M, Rodriguez J, Brown RC, et al. (2008) Efficacy of memantine on behavioral and psychological symptoms related to dementia: a systematic meta-analysis. Ann Pharmacother 42(1): 32-38.

- (2006) National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, Social Care Institute for Excellence (SCIE), National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Dementia: supporting people with dementia and their carers in health and social care. London: National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE)

- Raina P, Santaguida P, Ismaila A, Patterson C, Cowan D, et al. (2008) Effectiveness of cholinesterase inhibitors and memantine for treating dementia: evidence review for a clinical practice guideline. Ann Intern Med 148(5): 379-397.

- (2006) Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN). Management of patients with dementia. A national clinical guideline SIGN.

- Sobów T, Kioszewska I (2007) Cholinesterase inhibitors in mild cognitive impairment: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Neurol Neurochir Pol 41(1): 13-21.

- S Gauthier (2009) Management of dementia. 2nd edition, Informa Health care, UK Winston. A, Rosenthal RN (2002) Introduction to Supportive Psychotherapy. American Psychiatry Publishing: Washington, DC, 4.

- (1992) World Health Organization. The ICD-10 Classification of Mental and Behavioural Disorders: clinical Description and Diagnostic guideline Europe.