Effective Brief Interventions for Drug-using Traumatically Injured Patients

David C Maynard1*, Mark D Newmeyer2, Lee A Underwood2 and Andrew C Bernard3

1Center for Counseling, Health, and Wellness, USA

2Regent University, USA

3University of Kentucky, USA

Submission: May 10, 2017; Published: May 24, 2017

*Corresponding author: David C Maynard, Center for Counseling, Health, and Wellness, Lexington, KY, Post Office Box 24611, USA,Tel:859-229-8222 ; Fax:859-272-1477; Email: dmaynard@kycounseling.org

How to cite this article: David C M, Mark D N, Lee A U, Andrew C B. Effective Brief Interventions for Drug-using Traumatically Injured Patients. Glob J Add & Rehab Med. 2017; 1(5): 555575. DOI:10.19080/GJARM.2017.01.555575

Abstract

Screening and brief intervention (SBI) for alcohol is a requirement for trauma center verification in some states, but not for drug use, despite its associated harm to the individual and society. This study assessed the effectiveness of, and the role injury severity place in, SBI on drug-using patients admitted to a trauma center. Results indicate drug-using patients benefited from brief intervention as much as alcohol-using patients and injury severity does not change SBI efficacy. However, drug-using patients are less likely to report use than those using alcohol, no matter how severely injured. Implications for SBI in trauma care are discussed.

Keywords:Screening; Brief intervention; Trauma; Alcohol; Drugs

Abbreviations:SBI: Screening and Brief Intervention; AIS: Abbreviated Injury Scale; SOC: Stage of Change; LOTC: Level One Trauma Center; SAMSHA: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; NTDB: National Trauma Data Bank; ISS: Injury Severity Score; LTTC: Level Two Trauma Centers; MET: Motivational Enhancement Therapy; EAC: Excessive Alcohol Consumption; SAL: Serum Alcohol Level; UDA: Urine Drugs of Abuse

Introduction

Alcohol and drug use contribute to physical injury [1-5]. Despite multiple studies on the way injury and brief intervention prompt change in alcohol consumption [6], there have been very few studies regarding the change process relative to severity of physical injury, despite the literature establishing drug use as being problematic [4]. This study investigated the relationship between the abbreviated injury scale (AIS) and a clinician-assigned stage of change (SOC) to patients who used alcohol and/or drugs for nonmedical reasons and were admitted to an American College of Surgeons-verified Level One Trauma Center (LOTC).

The association between substance use and physical injury is clear. In the United States, there were 814,663 traumatic incidents in 2013. Of those, 42.3% were falls, 27.1% were motor vehicle crashes, 7.1% were struck by or against an object, 4.6% were from other modes of transportation, such as aircraft, 4.3% were from a cut or piercing, such as a stab wound, 4.2% were from a firearm, and 1.8% were from pedal cyclists. There are an additional 16 mechanism of injury categories that account for the remaining 6.8% of injuries. For the age group 25 to 34 and 45 to 54 are the number one mechanism of injury is motor vehicle crashes [7].

The fourth most frequent complication among trauma patients is a drug or alcohol withdrawal syndrome, at 7%. However, 52.2% of trauma victims were not tested. Of those tested, 24.4% were negative, and 9.8% were positive but beyond the legal limit and 3.8% were positive for trace levels. For drug use, 62.5% were not tested, while in those that were tested, 11.0% were negative, 7.4% were positive for illegal drug use, and 3.8% were positive for prescription drug use [7].

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [8] reported that in 2011, 9.4 million people (3.7%), ages 12 and above, had driven under the influence of illicit drugs in the past year, while 28.6 million people (11.1%) had driven under the influence of alcohol. Two years later, driving under the influence of drugs (9.9 million, or 3.8%) remained relatively unchanged, while driving under the influence of alcohol (28.7 million people, or 10.9%) increased slightly [9].

Statement of the Problem

Alcohol use is routinely addressed in LOTCs through brief interventions utilizing motivational enhancements. In 2006, the American College of Surgeons gave focus to LOTCs and mandated screening and brief interventions (SBI) for alcohol [10]. Miller, Lestina and Smith [11] have also demonstrated the importance of interventions with the drug using injured patient but SBI for drug use has not been mandated by the American College of Surgeons.

Alcohol and drug users had a 58% higher risk of being injured, and were almost four times more likely to be hospitalized than non-users. Persons only using drugs were at a 49% higher risk of being injured and alcohol-only users were at a 46% higher risk of being injured than non-users. Of patients specifically admitted to a trauma center, 24% were alcohol dependent as defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, whereas 18% had substance dependence. With such prevalence and relevance of alcohol and drug use in trauma patients, it is clear that trauma centers are well positioned to address drug use, alongside alcohol use, to effect change and reduce trauma recidivism [11].

Purpose of the Study

The purposes of this study were to explore the effectiveness of Motivational Interviewing on physically-injured patients, their admission of alcohol and drug use to healthcare providers, and the influence of injury severity.

Alcohol and Drug Use in Trauma

Zatzick et al. [12] examined the records of nearly 17,000 trauma patients. Blood alcohol concentrations were positive in 20.9%, negative in 60.2%, and not drawn in 18.9%. However, not all patients consented to participation in the study. The study cohort contained close to 900 patients. Blood alcohol concentrations were positive in 28.6%, negative in 56.1%, and not drawn in 15.3%. Of those in the study cohort, 18.1% had positive toxicology for cannabis, whereas 36.6% self-reported use. Regarding cocaine, 10.6% had a positive toxicology and 16.1% self-reported use. Regarding opiates, 4.1% had a positive toxicology, and 11.7% self-reported use.

A review of the electronic medical record of the study group found 23% had been diagnosed with alcohol abuse or dependence, 5.6% with cannabis abuse or dependence, 9.6% with cocaine abuse or dependence, 5.9% with opiate abuse or dependence, 3.8% with amphetamine abuse or dependence, and 7.3% with poly-drug abuse or dependence [12]. Cowperthwaite & Burnett [3] examined the National Trauma Data Bank (NTDB) and found nearly two million (1,926,244) records, of which 11.6% met study inclusion criteria (aged 16 and above, injury severity score between zero and 75, and gender recorded). The study group contained primarily males (72%) and those males were significantly (Chi-square, p< 0.001) more likely to have used alcohol or drugs pre-injury. Further, for those using alcohol only, the mean age was 36.3, the mean age of those using drugs only was 37.1, and the mean age of those using alcohol and drugs was 34.3. Those negative for substance use had a mean age of 42.1 years.

More interestingly, this study examined if pre-injury alcohol and drug use resulted in more severe injuries, as determined by the Injury Severity Score (ISS). Overall, the average ISS was nine. Those using alcohol only had a mean ISS of 11.2, drug only a mean ISS of 12.5, alcohol and drug a mean ISS of 11.5, and a mean ISS of 11.7 for substance negative. Cowperthwaite & Burnett [3] conclude that more significantly (p< 0.001) severe injuries occur because of drug use than when there is no drug use, but alcohol is not significantly associated with severe injuries (p = 0.08). Additionally, the researchers noted that major trauma, defined as an ISS equal to or greater than 15, was 28% in alcohol-only, 31.4% in drug-only, 28.5% in alcohol and drug, and 29% in substance negative patients.

The American College of Surgeons [10] initially responded to this early work by requiring all LOTCs and level two trauma centers (LTTC) to provide screening for alcohol use, with LOTCs being required to also provide brief intervention. This was the first national effort to reduce problematic alcohol use. In 2014, that requirement was extended to all trauma centers [13], with the aim to reduce trauma recidivism. At the time of this requirement’s implementation, there were no other mandates or best practice guidelines for drug use screening. In 2014, Love and Zatzick reported more than 80% of LOTCs screen for alcohol and drug use and LOTCs were more likely than LTTCs to provide intervention for alcohol use.

Neumann et al. [14] found trauma patients smoked (60%) and within the past year, 34% had used drugs. Further examination of drugs used found 31 to 32% used cannabis, five percent used ecstasy, six to seven percent used cocaine, one to two percent used opiates, and and three to five percent used other illicit drugs. Alcohol intake was 26 to 28 grams per deciliter (g/d) on average per week. Approximately one half had at-risk drinking, eight to nine percent had alcohol dependence, 12 to 14% had harmful alcohol use, with just over half having binge drinking-defined as more than six drinks-episodes. The AUDIT score ranged between six and 11 with an average of seven (intervention group) and eight (control group).

Interestingly, those patients with higher baseline alcohol consumption were more likely to not follow-up at six and 12 months (30 g/d versus 26 g/d, p = 0.014) and were alcohol dependent (12.7% versus 6.7%, p< 0.001). The intervention group was more likely to reduce alcohol consumption at both the six and 12-month follow-up. At six months, the first followup was conducted and the intervention group decreased alcohol consumption by 36%, whereas the control group decreased out all consumption by 20% (p = 0.006). At 12 months, the second follow-up was conducted, and the intervention group had a 23% decrease in alcohol consumption from baseline, whereas the control group had an 11% decrease in alcohol consumption from baseline (p = 0.02). Half of the study participants in both groups were in precontemplation, nearly one third in contemplation, and one fifth in action. The greatest impact of the intervention was observed in those assessed at a contemplation stage of change at their first follow-up (p = 0.010; [14]).

Stages of Change and Motivational Interviewing

Prochaska and DiClemente [15,16] began a discussion on the process of change and how that occurs in individuals, and then applied that to smoking [16]. The authors discuss an exploration of the change process in18 dominant therapy systems and discovered five common stages, with differences existing only in which stage is emphasized. Their review found the systems gave focus to experiential or environmental processes, with agreement on different constructs: conscious raising, choosing, catharsis, conditional stimuli, and contingency control (from left to right, the authors found each process moved from more experiential to environmental processes).

According to Prochaska and DiClemente [15], conscious raising is found in 16 of the 18 reviewed psychological systems and dates back to Freud in his attempts to make the unconscious conscious. The authors state that therapies applying this process attempt to increase the information available to the individual in order to make the best decision regarding the situation before him or her. If the therapy is more experientially based, conscious raising comes in the form of feedback, and if by environmental events, it is referred to as education.

Prochaska and DiClemente [16] state the process of change is unique to a therapy and the content is derived from the therapy’s view of personality and psychopathology. The Transtheoretical Model gives emphasis and focus to the process of therapy, as opposed to its content, which will change from one person to another. Because the Transtheoretical Model is a model of change, it is able to account for change, irrespective of the involvement in therapy.

Prochaska and DiClemente [16] initially identified four of what would eventually become five stages of change: precontemplation, contemplation, action, and maintenance. This is not to say that change is a dichotomous event, but instead a process. McConnaughy, DiClemente, Prochaska, and Velicer [17] describe individuals in precontemplation as believing they are not the ones in need of change, but others or the environment. Contemplation stage defined as having an awareness of a problematic situation, an interest in determining if it is solvable, and an interest in determining whether the resources necessary to make those changes are appropriate. Balmford, Borland, and Burney [18] found that the strongest prediction of individualsbeing in contemplation were “serious thoughts about quitting in the previous two weeks” (p. 147).

Anatchkova, Velicer, and Prochaska [19] regard preparation as being “characterized by readiness to change behavior in the next 30 days and at least one 24-h quit attempt” (p. 360). Velicer, Hughes, Fava, Prochaska, and DiClemente [20] identified action as beginning when the individual makes overt attempts at ceasing the undesired behavior, and notes this stage is zero to six months in duration. Maintenance stage is classified as beginning when the individual completes the initial six months of having no longer engaged in the undesired behavior and continues until the behavior is no longer deemed a problem.

Creating behavioral change is seldom easy. Miller and Rollnick [21] developed a clinical style to help clinicians assist individuals increase their motivation toward, and overcome ambivalence to, behavioral change. MI is not concerned with techniques so much as it is concerned about the “spirit” of the treatment [21]. This spirit is understood to include three important traits: collaboration, evocation, and autonomy. In addition to the components of MI, there are four general principles in the application of MI: empathy, discrepancy, rolling with resistance, and supporting self-efficacy. MI can be summed up as utilizing change talk as the “primary method for developing discrepancy” and resolving ambivalence about change (p. 83).

Miller and Rollnick [22] write that it is not intended to trick people into behaviors they do not endorse, but instead, drawing out from them what they want. MI is not a “technique” that can be easily and simply done, but more akin to a method, requiring practice over time. MI is not a decisional balance, where a 2-by-2 table is utilized, or a pros and cons list. MI is not motivational enhancement therapy (MET), where assessment feedback is provided, such as the results of an alcohol screening score. MI is not cognitive behavioral therapy, where interventions such as conditioning, contingencies, cognitive challenging, the learning of coping skills and more are employed. MI is not client-centered (Rogerian) therapy, as MI is goal-oriented, where the counselor seeks to elicit “change talk.” MI requires the counselor to be flexible in responses from the person, on a moment-by-moment basis, and focused on the purpose of change, even when the person is irrational and contradictory. MI is not comprehensive; it is intended to assist a person in moving from ambivalence to action, where other approaches take over. Finally, MI is not the transtheoretical model of change (TTM), discussed previously.

Lundahl, Kunz, Brownell, Tollefson, and Burke [23] found MI’s effect size (g = 0.22 [confidence interval (CI) 0.17-0.27]), though small, was statistically significant (z = 8.75, p< 0.001). Because MI has been reported as not being effective for all problem types (e.g., Burke, Arkowitz, & Menchola [24], they explored the effect size of MI in changing substance use (alcohol, k = 68; miscellaneous drugs, k = 27; tobacco, k = 24; marijuana, k = 17) and found statistically significant outcomes. However,was generally found to be as effective as other forms of care, including 12-step programs and cognitive behavioral therapy.

Gaume, Bertholet, Faouzi, Gmel, and Daeppen [25] studied one session of MI to change alcohol consumption, or reinforce changes already made, with a focus on eliciting change talk. Expression of no ability, desire, and need to change was a significant predictor of poor outcomes at six-month followup. The expression of ability, desire, and need to change only “approached significance (p = 0.08).” The researchers were unable to support the hypothesis that MI’s change talk will predict actual change. This could be attributed to many factors, such as inter-rater reliability being low. Though actual change was not established based on change talk, sub-dimensions of change talk were established, and this is supported by other studies [26-28]. However, other studies have supported change talk as a predictor of behavioral change [24-28] and that practitioners can correctly predict the outcome of MI.

Strang and McCambridge studied 105 interventions averaging 36 minutes with three core topics: “(1) a rapportbuilding opening; (2) identification of good things and less good things about drug use; and (3) values and goals elaboration.” Other topics in approximately half of the interventions included “‘Risks and Problems,’ ‘Decisional Balance,’ and ‘Controlled Drug Use.’” Cannabis was the most frequently discussed drug, while alcohol and cigarette use were the least salient. After the intervention, the practitioner rated the participants’ stages of change. The researchers found the MI practitioner could predict outcome at the three-month follow-up.

Injury Severity and Substance Use

The AIS began in 1971 and is maintained by several disciplines and organizations with several principles guiding its development since its inception. Some of those principles are to: ranks injuries by severity, create standardized terminology to describe injuries, be available for varying types of injury mechanisms, support data collection, organize injuries by anatomy (not physiology), exclude long-term consequences of injury, reflect injury in healthy adults, reflect each single injury in severity by a time-independent value, describe an injury in relation to the whole body. In summation, “the AIS is an anatomically-based, consensus-derived, global severity scoring system that classifies each injury by body region according to its relative importance on a 6-point scale” (p. 2). The dimensions of injury severity include variables such as threat to life, mortality, tissue damage, length of hospitalization, cost, treatment complexity, disability and impairment, and quality of life. The AIS is frequently used in research.

The morbidity and mortality of injured individuals is significant. Stübig et al. studied individuals involved in roadrelated injuries between 1999 and 2010. Of those individuals that succumbed to their injuries, 2.2% had a negative BAC and 4.6% a positive BAC (p< 0.0001). Of those severely injured (anInjury Severity Score >15), eight percent had a positive BAC and 3.6% a negative BAC (p< 0.0001). The researchers also noted that alcohol-intoxicated individuals were more likely to be traveling at a higher speed at impact than those not intoxicated (p< 0.0001). Level of BAC was not significant for injury severity or speed at the time of injury.

Talving et al. describe results like those just reported. BAC was not significantly associated with injury severity, hypotension at admission, Glasgow coma score, major complications, intensive care unit or hospital length of stay. Mortality was significantly lower in individuals with a BAC greater than 0.08 mg/dL compared to those with a BAC less than 0.08 mg/dL, including a negative BAC (p = 0.037); the same held true with an Injury Severity Score greater than 15, but lost significance at or above 25.

In 2006, a conservative estimated cost to the US was $1.90 per drink, or collectively, $223.5 billion. Excessive alcohol consumption costs (EAC) were born by 41.5% of the drinkers and their families, with the remainder being bore by federal, state and local governments report the median cost to state governments at $1.3 billion annually, and a median cost per person of $703 annually. Lost productivity accounts for more than 70% of the annual median cost of EAC, and healthcare costs were more than 11%.

Rationale for the Study

Multiple studies have identified alcohol and substance use as playing a key role in injuries necessitating hospital admission. Studies have identified and supported implementation of SBI for alcohol and mental health concerns, specifically posttraumatic stress disorder and depression, but have failed to establish the effectiveness of brief intervention for substance use.

However, studies have not explored the impact of a brief intervention on substance use and subsequent trauma recidivism or the role injuries play in altering both alcohol and substance use after intervention. Of those studies giving focus to substance use and change in trauma patients, study participants were assessed for substance use prevalence and disorders, not readiness to change, with some calling for trauma centers to address drug use [2,4,11]. Fuller, Diamond, Jordan, and Walters found evidence to support the use of a substance abuse consultation team in motivating patients to accept a referral for substance abuse treatment. This study addresses gaps in knowledge by first identifying the relationship between the AIS and SOC, and second, determining the influence of injury severity on patients’ admission of alcohol and/or drug use, and reporting alcohol use versus drug use.

Research Questions

As healthcare costs continue to rise, interest will also increase in how to best treat individuals for specific diseases, including substance use. Administrators and healthcare providersnecessarily need to understand how to best treat the trauma patient with problematic substance use in order to prevent and reduce recidivism. This study is designed to facilitate that understanding by answering these research questions:

- Is there a relationship between the Abbreviated Injury Score (AIS) and a stage of change assigned by a counselor to patients who used alcohol and/or drugs for nonmedical reasons and were admitted to a Level One Trauma Center?

- How likely will patients admit their substance use (alcohol, drugs, or both) based on the type of toxicology result (positive for alcohol, drugs, or both) and the AIS (continuous)?

- Are patients more apt to report alcohol use than drug use, as confirmed by toxicology?

Understanding the role injury may or may not play in a patient’s decision to change is crucial to understanding how healthcare providers approach patients. Without further understanding, it is difficult to know how to capitalize on the injury to effect change in substance use behavior.

Method

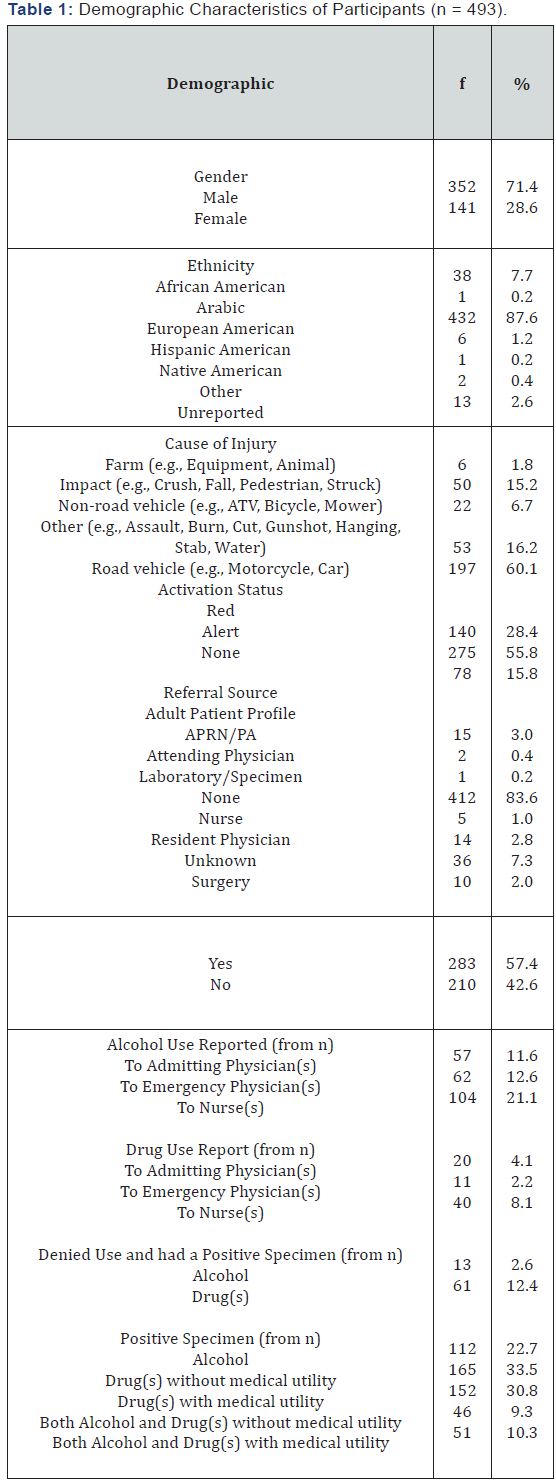

Patients (n = 493) included in this study were admitted to a LOTC. The trauma database and medical record was queried for patients seen by the counselor, and those patients’ AIS, admission of alcohol and drug use, toxicology results, and SOC was made. A significant quantity of patients’ data were analyzed using a Pearson Correlation, Logistic Regression, and McNemar test.

Research Design

This study was be a quasi-experimental, correlation study design to determine if there is a positive correlation between the clinician’s rating of the patient stages of change and the AIS. This study design allowed the researchers to determine the relationship to the patients’ medical condition and whether they desire to change behaviors that may have contributed to their injury requiring hospitalization, after receiving a brief intervention. Admission of using alcohol and/or drugs were examined by patient report to both their physician and nurse, and utilized a cluster analysis research design. To analyze whether patients are more apt to report alcohol use than drug use employed a mean analysis.

Population and Sampling: The research subjects for this study were inpatients at a LOTC facility, admitted for an injury and having both serum alcohol level (SAL) and urine drugs of abuse (UDA) reported, and receiving a brief intervention with a counselor-assigned SOC. Approximately one third of trauma patients have both blood alcohol levels and urine drugs of abuse toxicology reports within three hours of admission. Completion of the LOTC’s questionnaire were administered by bedside nurses directly to the patient. Part of the normal routine examination bythe physician is to interview his or her patient on the patient’s use of alcohol and drugs. The estimated sample size needed to answer these questions is 150 and the actual sample size is 493.

Data Collection Procedures

Approval from the institutional review board of the study site was obtained, as well as approval from the human subjects review board of the degree granting institution. Data was queried for patients admitted to the study site from September 1, 2008, through September 30, 2014. Patients under the age of 18 were excluded from this study.

Data points from the trauma database analyzed included: age, gender, race, stage of change, UDA, SAL, patients’ length of stay, occupation, mechanism of injury, location of injury (e.g., street, home, etc.), trauma activation status (red or alert), surgery occurrence, and the AIS. Trauma database registrars are Certified Abbreviated Injury Scaling Specialists or are preparing to be certified and are under the supervision of credentialed registrars. Acknowledgement of alcohol and substance use was obtained by reviewing physician and nursing documentation. Specifically, nurses administer the CAGE and a single drug use question to identify those in need of a brief intervention. The study site utilizes SAL to detect alcohol and immunoassays with confirmation by gas chromatography-mass spectrometry (GC/ MS) for UDA.

Data Cleaning

All 493 patients were identified as being eligible for inclusion in at least one analysis. Each patient had AIS, but not all had a SOC and were excluded from the analysis requiring it. SAL and UDA were coded one if positive and zero if negative. If a patient reported to a nurse or a physician alcohol or drug use, the patient’s response was coded one for positive and zero if negative. In cases where patients denied use to one counselor, but acknowledged use to another, the response was coded positive.

Results

The primary purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of brief intervention on patients admitted to a LOTC in relation to injury severity. A secondary purpose was to examine the likelihood of a patient acknowledging to one or more of their medical and nursing providers current drug use. A third purpose was to determine the influence of injury severity on reporting drug use and increases the likelihood of a higher SOC.

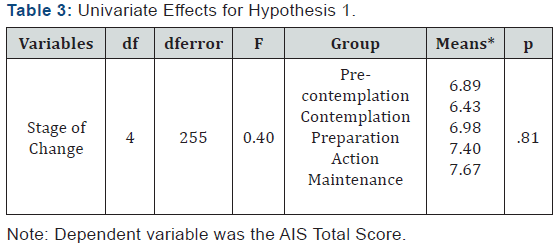

Of those the 493, 129 patients (26.2%) had an assignment of one of the following categories or SOCs: Not applicable (n = 13, 10.1%), Unable to obtain (n = 21, 16.3%), Pre-contemplation (n = 36, 27.9%), Contemplation (n = 20, 15.5%), Preparation (n = 21, 16.3%), Action (n = 11, 8.5%), and Maintenance (n = 7, 5.4%). Due to the inability to discern the impact of the brief intervention on patients with the first three categories, they werenot included in the analysis. Further, patients assigned to the Action and Maintenance stages were not included in analysis, as this requires the patients to already be working toward change of their alcohol and/or drug use.

Descriptive Statistics

During the study period, a total of 17,159 patients were admitted to the study site, with a mean length of stay of 7.4 days and a range of zero to 67 days and 0.6% had a 30-day readmission (n = 3). Please see Table 1 for additional demographics and Table 2 for AIS. To examine the linear correlation between the AIS total score and the SOC score, a Pearson correlation coefficient was used. Preliminary results indicated a non-significant, weak, positive correlation, r (4) = .04, p = .48. Thus, this hypothesis was not supported (see Table 3).

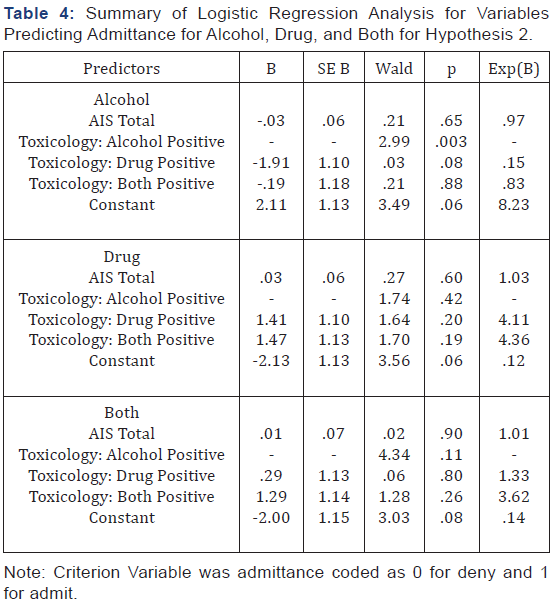

Three, binomial, logistic regressions were used to analyze toxicology total score, AIS total score, and admitting ethanol, drug use, or both. A binomial logistic regression allows for a dependent variable to have only two possible outcomes. In the present analyses, the two possible outcomes are admission or denial. Three regressions were used to analyze each category: use of alcohol, use of drugs, and use of alcohol and drugs. The first analysis did not support AIS total scores as a variable in patients admitting use, but was supported for positive alcohol toxicology results. The second analysis did not support hypothesis 2 for AIS total or toxicology scores. The third analysis, the impact of AIS total scores and toxicology results on the likelihood of admitting both alcohol and drug use (admit/deny), was not supported (see Table 3).

In analysis one, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict admitting alcohol use with AIS total scores and toxicology results as predictors. A test of the full model was statistically significant, indicating that the predictors as a set reliably distinguished between patients who admit and patients who deny alcohol use (chi square = 14.84, p = .002 with df = 3). Nagelkerke R2 of .181 indicated a modest relationship between prediction and grouping. Prediction success overall was 62.9% (34.2% for denying and 79.1% for admitting). The Wald criterion demonstrated that only toxicology results made a significant contribution to prediction (p = .003). AIS total score was not a significant predictor. Exp(B) value indicates that when toxicology results are raised by one unit the odds ratio is eight times as large and therefore patients are eight more times likely to admit alcohol use.

In analysis two, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict admitting drug use with AIS total scores and toxicology results as predictors. A test of the full model was not statistically significant, indicating that the predictors as a set were unable to reliably distinguish between patients who admit and patients who deny alcohol use (chi square = 2.79, p = .43 with df = 3). Nagelkerke R2 of .04 indicated a poor relationship between prediction and grouping. Prediction success overall was 64%. The Wald criterion demonstrated that neither the toxicology results nor the AIS total score were significant predictors. The odds ratio for these variables indicate little change in the likelihood to admit drug use.

In analysis three, a logistic regression analysis was conducted to predict admitting alcohol and drug use with AIS total scores and toxicology results as predictors. A test of the full model was not statistically significant, indicating that the predictors as a set were unable to reliably distinguish between patients who admit and patients who deny alcohol use (chi square = 4.38, p = .22 with df = 3). Nagelkerke R2 of .07 indicated a poor relationship between prediction and grouping. Prediction success overall was 78%. The Wald criterion demonstrated that neither the toxicology results nor the AIS total score were significant predictors. The odds ratio for these variables indicate little change in the likelihood to admit alcohol and drug use.

The third analysis found patients are likely to admit alcohol use than drug use. A McNemar test may be used with paired nominal data. In this present analysis, one nominal dataset was admitting alcohol use: yes or no, paired with the second dataset admitting drug use: yes or no. This test was utilized to examine if a greater proportion of patients would admit alcohol or drug use. For this sample, 91.2 % of the respondents admitted the truth about their alcohol use, where as only 41.2% admitted the truth about their drug use (see Table 4). These percentages were significantly different from each other based on the results of the McNemar test of dependent proportions, χ2 (1, n = 102) = 40.98, p< .001. The odds ratio was 0.09 with a 95% confidence interval extending from 0.03 to 0.22 (Table 5).

Discussion

This study demonstrates trauma patients using drugs are just as likely to benefit from SBI as are those using alcohol only, no matter how severely injured they may or may not be. Therefore, patients across the spectrum of injury severity will be just as likely to benefit from SBI. In all five SOC, the range of means were from 6.43 (contemplation) to 7.67 (maintenance), indicating patients were just as likely to be rated at precontemplation as they were maintenance. This provides trauma surgeons and healthcare systems evidence for which they need to support providing SBI to trauma patients.

This study considered if patients would be more likely to report alcohol use, drug use, or alcohol and drug use, the more severely injured they were, and as confirmed by serum alcohol and urine drugs of abuse. Significantly, this study found 91% of patients using alcohol only will report that use to a healthcare provider and this was confirmed by and corresponded with SAL. Injury severity did not influence admission of alcohol use. It stands to reason that the higher the injury severity, the more likely an individual is willing to admit having used substances, yet this study finds injury severity plays no role. That is, results indicate it does not matter how severely injured a patient may be, they are not likely to admit substance use. Further, only 41% will report drug use when asked by a healthcare provider. Drug use was analyzed with the UDA and AIS total score, and were not significant. Patients are unlikely to admit use of alcohol and drugs, when compared to their SAL and UDA, and injury severity did not influence the likelihood of their admission of using alcohol and drugs. Because of patients’ lower likelihood of admitting substance use, patients will likely gain greater benefit if screening involves more than a verbal question. However, trauma patients are significantly more likely to admit using alcohol than they will admit using drugs.

These data support the concept there is a difference between drug-using trauma patients, regardless of their use of alcohol, from trauma patients using alcohol-only. Such a difference may also play a role in how healthcare providers address drug-use in the patients, particularly where injuries are concerned. The literature to-date is largely concerned with the use of alcohol prior to sustaining a traumatic injury, and drug use a secondary concern. This study demonstrates drug use is not a separate, addon issue that can be as easily addressed. Instead, consideration of screening instruments beyond a verbal question ought to be considered.

It is recommended that trauma patients unable to participate in a verbal question regarding their substance use automatically have their urine tested for substances. In many cases, patients unable to participate in their care verbally may be unable to do so long after any substances have cleared their bodies. However, those patients able to participate in a verbal question and acknowledges substance use ought not to have their urine tested, and if they deny substance use, then verification be made through urine testing.

Implications for Trauma Centers

Trauma healthcare providers have the opportunity to reduce recidivism across the spectrum of injury severity. Patients are unlikely to report their drug use to a healthcare provider, even when asked. However, this study demonstrated they are just as likely to benefit from a brief intervention. Therefore, UDAs will be need to identify which patients need a brief intervention. Because patients are likely to admit their alcohol use it is unnecessary to obtain a SAL. If the trauma patient admits using alcohol, according to this study, they are unlikely to use drugs and therefore can forego UDA. However, this study demonstrated patients are unlikely to admit use of drugs and therefore, testing all patients for drug use is advisable.

Implications for Allied Healthcare Providers

Frequently, hospital social workers discharge nurses are responsible for arranging the care of patients once discharged. By being aware of a patient’s alcohol and/or substance use status, and the results of the BI, they can aid in reinforcing the patient’s decision to reduce their consumption. This will aid in making the SBI a full trauma center system responsive to the causes of injury. Additionally, they will also be able to participatein referring, and arranging for referral, to addiction treatment services.

Limitations of the Study

Using injury severity as a predictor of whom to screen will not capture those that may benefit from a brief intervention. Identifying patients in need of brief intervention can be a complicated process for multiple reasons, which presented this study with limitations. It can be difficult to identify patients that will be considered trauma. Some patients present as activations, and are discharged, while the majority are not activated. At times, the reason for hospital presentation is not clear (e.g., brain bleed due to natural causes or a fall). Administering a screening questionnaire can be challenging because patients will move through various locations in a LOTC through the course of their stay and not all patients will pass through the same location at the LOTC. Throughout the hospitalization, the patient is likely to be cared for by multiple physician teams and nurses, creating a challenge to identify which providers to train.

The only reliable way to screen trauma patients for alcohol and drugs at the study site was to include serum alcohol and urine drugs of abuse levels on the trauma activation order set at admission. However, a more robust method of identifying patients ought to be considered, and will most likely require investment in the education of physicians and nurses as to the importance of SBI, and systems establish to ensure all trauma patients are screened. A larger sample size at multiple LOTCs would be useful in determining the role injury severity plays in patients reporting their alcohol and drug use. This study was also hampered by the fact a stage of change assessment tool was not used. Such a tool would provide far more information regarding patients that change and, potentially, which type of injury aids in compelling patients towards change. This study was also limited by patients primarily being activations, which is one-third the population, as opposed to all trauma patients.

Recommendations for Future Research

Drug use cessation after trauma needs to be and will aid in healthcare decision-making and legislative efforts. A SOC assessment before and after the brief intervention for trauma patients will help. Comparing that data with the AIS may indicate where the best opportunities for trauma centers lie. Further understanding of responses to brief intervention after a particular injury type and severity may help, along with the cause of injury, has opportunity. A study examining the best means by which to implement SAL and UDA would have positive ramifications.

Conclusion

Injury severity does not play a role in the response to a brief intervention, yet patients respond equally well to brief interventions. Trauma patients are significantly likely to admit alcohol use, except where there is drug use. While it is appropriate to identify patients using alcohol via a verbal screen,drug use will require a UDA screen, and if positive, a SAL.

References

- Cherpitel CJ (1993) Alcohol and injuries: A review of international emergency room studies. Addiction: 88: 923-937.

- Cherpitel CJ & Borges G (2002) Substance use among emergency room patients: An exploratory analysis by ethnicity and acculturation. American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse : 28(2): 287-305.

- Cowperthwaite MC Burnett MG (2011) Treatment course and outcomes following drug and alcohol-related traumatic injuries. Journal of Trauma Management & Outcomes: 5(3): 1-9.

- Martins SS, Copersino ML, Soderstrom CA, Smith GS, Dischinger PC, McDuff DR, Gorelick D A (2007) Risk of psychoactive substance dependence among substance users in a trauma inpatient population. Journal of Addictive Diseases: 26(1): 71-77.

- Zatzick D, Donovan DM, Jurkovich G, Gentilello L, Dunn C, Russo J, Rivara FP (2014b) Disseminating alcohol screening and brief intervention at trauma centers: A policy-relevant cluster randomized effectiveness trial. Addiction : 109(5): 754-765.

- Gentilello LM, Ebel B E, Wickizer TM, Salkever DS & Rivara FP (2005) Alcohol interventions for trauma patients treated in emergency departments and hospitals: A cost benefit analysis. Annals of Surgery :241(4): 541-550.

- American College of Surgeons (2014a) National trauma data bank annual report 2014.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2012) Results from the 2011 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (2014) Results from the 2013 national survey on drug use and health: Summary of national findings. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

- American College of Surgeons (2006) Resources for the optimal care of the injured patient 2006. Chicago: Author.

- Miller TR, Lestina D C Smith GS (2001) Injury risk among medically identified alcohol and drug abusers. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research :25(1): 54-59.

- Zatzick D, Donovan D, Dunn C, Russo J, Wang J, Jurkovich G, Gentilello L M (2012) Substance use and posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms in trauma center patients receiving mandated alcohol screening and brief intervention. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment: 43(4): 410- 417.

- American College of Surgeons (2014b) Resources for optimal care of the injured patient (6). Chicago IL: Author.

- Neumann T, Neuner B, Weiss-Gerlach E, Tønnesen H, Gentilello LM, et al. (2006) The effect of computerized tailored brief advice on at-riskdrinking in subcritically injured trauma patients. Journal of Trauma : 61(4): 805-814.

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC (1982) Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 19(3), 276-288.

- Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC (1983) Stages and process of selfchange of smoking: Toward an integrative model of change. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology: 51(3): 390-395.

- McConnaughy EA, DiClemente CC, Prochaska JO, Velicer WF (1989) Stages of change in psychotherapy: A follow-up report. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice 26(4): 494-503.

- Balmford J, Borland R, Burney S (2008) Is contemplation a separate stage of change to precontemplation? International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 15: 141-148.

- Anatchkova MD, Velicer WF, Prochaska JO (2006) Replication of subtypes for smoking cessation within the precontemplation stage of change. Addictive Behaviors 31(7): 1101-1115.

- Velicer WF, Hughes SL, Fava JL, Prochaska JO, DiClemente CC (1995) An empirical typology of subjects within stage of change. Addictive Behaviors 20(3): 299-320.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S (2002) Motivational interviewing: Preparing people to change. Guilford Press, New York, USA.

- Miller WR, Rollnick S (2009) Ten things that motivational interviewing is not. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy 37(2): 129-140.

- Lundahl BW, Kunz C, Brownell C, Tollefson D, Burke BL (2010) A metaanalysis of motivational interviewing: Twenty-five years of empirical studies. Research on Social Work Practice 20(2): 137-160.

- Burke B L, Arkowitz H, Menchola M (2003) The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinincal Psychology 71(5): 843-861.

- Gaume J, Bertholet N, Faouzi M, Gmel G, Daeppen JB (2013) Does change talk during brief motivational interventions with young men predict change in alcohol use? Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment: 44(2): 177-185.

- Amrhein P C, Miller WR, Yahne CE, Palmer M, Fulcher L (2003) Client commitment language during motivational interviewing predicts drug use outcomes. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 71(5): 862-878.

- Baer JS, Beadnell B, Garrett SB, Hartzler B, Wells EA, Peterson PL (2008) Adolescent change language within a brief motivational intervention and substance use outcomes. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors: 22(4): 570-575.

- Gaume J, Gmel G, Daeppen JB (2008) Brief alcohol interventions: Do counsellors’ and patients’ communication characteristics predict change? Alcohol and Alcoholism: 43(1): 62-69.