Bodies in Motion: Self-care, Effort, and Discipline in an Ethnography with Weightlifting Practitioners

Aparecido Francisco dos Reis*

College of Humanities, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, rua ouro branco, 97, Brazil

Submission: April 01, 2024; Published: April 25, 2024

*Corresponding author: Aparecido Francisco dos Reis, College of Humanities, Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, rua ouro branco, 97, Brazil

How to cite this article: Aparecido Francisco dos Reis*. Bodies in Motion: Self-care, Effort, and Discipline in an Ethnography with Weightlifting Practitioners. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2024; 13(5): 555874. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2024.13.555874

Abstract

This article is part of a survey of young bodybuilders at a gym in Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. It focuses on the discussion around exercises’ routine processes, motivations, perceptions, and representations of the corporeality of the practicing subjects, as revealed in observations and in-person conversations. Using ethnography as a method, the approach to the subjects took place through participant observation, in which the researchers took part in the daily routine of the gym. The results discussed here show that the gym is a space for social interaction, learning, and valuing discipline to build and maintain carved bodies.

Keywords: Corporeality; Discipline; Ethnography; Self-policing; Bodybuilding practices

Introduction

Ethnographies of the body within bodybuilding gyms have been produced quite significantly in current anthropology. We could identify 1,430 results of articles and books on the subject on Google Scholar, most centered in the southern, southeast, and northeast regions. Among these studies, we highlight, according to our research, the studies by Silva and Ferreira [1], in which they aim to “analyze and discuss how masculinities are exercised in bodybuilding, considering the rituals of initiation to pain in bodily practices” (p. 160), and Cesaro’s [2], in which he follows a group of men who attend a bodybuilding gym in the southern area of Porto Alegre, studying their body care practices, aiming to produce ideal bodies to contemporary aesthetic standards.

When we restrict the search on the same site to studies on the subject in Mato Grosso do Sul or the Center-West region, Google Scholar continues to show the same results as before. Thus, this research could be the first approach to local anthropology using ethnography for the subject in question. This field research led us to consider how, in contemporary society, young people resignify their bodies through training in bodybuilding gyms in Campo Grande, Mato Grosso do Sul. This article is part of a research project about the regulars at two network franchises of bodybuilding gyms, which we identified as S and E. However, this article will only discuss some of the research results at the S gym.

What do we mean when we talk about thinking about corporeality? We are referring to social construction, which is also individual. Examining oneself and reflecting on how social traits, patterns, stereotypes, and frustrations intertwine in our being involves an active process. To think about the body is to go beyond externalization; it is to travel to an even more subjective plane whose purpose is to decipher everything that subjects silence but manifests in gestures, behaviors, looks, and postures. In modern times, the demands of a consumer market, the exercise of self-control, exhaustive training, and competition with oneself materialize corporeality as part of a set of difficulties to be faced on the path to the perfect body. Through an ethnographic approach, we sought to understand the passion for exercising of a group of young people aged between 22 and 30, highlighting issues related to the dense description of the location, the motivations for training, the notion of the ideal body, and the routine of exercises in the process of making the body.

The Methodology

The ethnographic work allowed a more detailed description of the gym, understood as a space where reproduced routines contribute to practicing body worship. In addition, in the field, we played the role of apprentices in bodybuilding training, which allowed us to have more significant contact with the individuals since the interviews took place at the same stage where the bodybuilding practices were reproduced. Intensive access to the field and constant contact with the practitioners allowed us, throughout the investigation, to redefine our orientations and preconceptions about body care, allowing social categories to emerge that had not been contemplated initially. In this context, ethnography is the first stage of cultural research: fieldwork (process) and a monographic study (product). Following the anthropological tradition of its creators [3,4], ethnography studies and describes the culture of a given society through participant observation and data analysis. Thus, ethnographic work encompasses what people do, what they say they do, and what they think they should do.

Our personal history as outsiders in the gym and our intentions therein (which have always been academic and not sporting) became essential guides to trimming the work by allowing us to look at ourselves as part of the research, avoiding falling into positivist biases that turn the young people in the picture into “objects.” Gym S was chosen because of its accessibility compared to other gyms in neighborhoods further away from the city center, as it is located in the central region of the capital (Campo Grande). It has been a licensed facility for around ten years. It is open daily from 6 am to 11 pm, Saturdays and Sundays until 6 pm. The monthly fee varies according to the type of plan the customer purchases. On the other hand, the informants pointed out that the local administrators do not limit the days or the number of hours to train, which many of them consider beneficial, as it allows them to have “greater freedom” to organize the rest of their work. They also highlight that the gym has modern equipment, air conditioning, and adequate hygiene in the space. Most attendees do so after leaving work or their studies, pass through an automated entrance and exit control turnstile, and instructors receive them to organize the training.

The facilities’ spatial distribution was carried out in what used to be a Chinese-branded car garage, with ample space for muscle training machines and aerobic training classes such as dances, treadmill runs, and pedaling exercise bikes. As this is an ethnographic study, its object study was constructed through our visits to the field and the in-person conversations we carried out in the gym. Our personal experiences are also reflected in the field diary sheets, along with the visual records of the premises.

In this way, we tried to get closer to a reflexive sociology. Therefore, and to avoid objectifying the young people who took part in the research, from the outset, we preferred to use the term social categories rather than units of analysis. This decision allowed us to capture body care work from the actors’ perspective. The social categories they worked with were as follows: Why young people attend the place, the ideal body, and the work and care of the body identified in the daily exercise routine. Subsequently, the place’s description revealed that despite having ample space and lots of equipment, members often have to wait for their colleagues to finish their routines before doing theirs or taking turns on the equipment.

However, informants say that they sometimes queue to use specific machines, which means changing their workout until the machine for a particular type of exercise is available. The images in the spaces, mirrors, machines, work elements, and television screens switched on at various points in the hall, but especially in front of the treadmills and exercise bikes, remind us of the type of body that can be built in this place using the resources available. We used the term “bodybuilding” to refer to the informants’ statements about the idea of an ideal body, along with small details related to auditory and visual aspects, such as the clinking of metal and the arrangement of weights, noises of moving machinery, and the predominance of an environment with music and televisions on, but contradictorily, most of the regulars opt to use headphones with their mobile phones, in which they listen to the content of their choice. We also observed the constant cleansing of bodily fluids such as perspiration by young people, whether they were training on machines to gain muscle mass or using aerobic machines, the latter more often used by women and men with a greater fat mass than desired. They identify this type of activity as “cardio” or “doing cardio,” and from the point of view of the more experienced practitioners, it is a type of exercise for beginners. We noticed that the more experienced ones do it just to warm up for the exercises on the weightlifting machines. There is a demonstration of suffering in all cases, especially for beginners. However, groans and panting can be seen and heard even by the most experienced practitioners as signs of their daily effort to build their bodies.

Over time, individuals train their bodies and minds to withstand the exercise load, acquiring skills, knowledge, and habits that facilitate and optimize training. One example is the use of protective covers, essential to prevent damage to the skin of the hands, but some display their calluses with a particular pride. The material of the machines, combined with the sweat itself, irritates the palms of the hands, which is why the use of gloves makes exercising less painful. Likewise, the use of protective clothing means a certain permanence on site. A beginner does not wear gloves, but an expert does because they already have experience working the muscles and a certain ease with strength machines.

Discussion and Results

Modernity, the period that we focus on in the West, from the 16th century onwards, results from a long process of discipline and self-observation of bodies. In his book “The Civilizing Process,” the German sociologist Norbert Elias [5] conducts a detailed investigation into the genesis of the formation of what is today, for us, the average civilized body. The socialization of young children, from the earliest formations of court societies, consisted - as it still does today - of learning a series of bodily controls. From an early age, one learns how to walk among others, eat in the presence of strangers, and control bodily impulses in public. The creation of the modern private sphere in liberal societies is inseparable from the introduction of mechanisms to control impulses and affections in public life. Affective and bodily self-discipline is the condition of subjects’ engagement in the social order, as shown by Foucault [6], for whom voluntary submission is the subjective arm of power. Continuous self-policing is the price to be paid for modern life, especially in cities. In the 18th century, we discovered the body as an inexhaustible source of power, as a machine, system, and discipline. It is at once docile and fragile, something that can be manipulated and easily tamed; in sum, susceptible to domination. The discipline of the 17th and 18th centuries is different from any compulsory discipline previously applied; it largely departs from the principles of enslavement and domesticity of the classical eras; it is a use of the body for specific purposes. It manufactures docile, submissive, highly specialized bodies capable of performing countless functions.

In “Discipline and Punish” (1987), Foucault explains how, at the end of the 17th century and early 18th century, the relationships between control mechanisms and power, previously exercised through physical punishment on bodies, transformed into an efficient structure of surveillance and discipline of bodies. In the author’s words: Learning how to behave, move, be precise, and have rhythm. Gestures are fabricated, and feelings are produced. This training is the result of the application of positive techniques of subjection based on pedagogical, medical, sociological, and physical knowledge, etc. The body becomes useful and efficient, but at the same time, it becomes docile and submissive: the body only becomes a useful force if it is at the same time a productive and submissive body [6].

The human body then becomes an instrument and object of power; this method that allows control and dominance, its correct training in the manufacture of submissive bodies, is called discipline. The norm tends towards homogeneity since it functions as a rule; in this way, deviations and differences have their purpose since they provide a measure to categorize a whole species of individuals. This disciplinary power will not only be applied to the individual’s body. However, it will also be directed at social bodies and will be responsible for hierarchizing and classifying subjects in the social domain. As Foucault: These were always meticulous, often minute, techniques, but they had their importance: because they defined a certain mode of detailed political investment of the body, a ‘new micro-physics’ of power, and because, since the seventeenth century, they had constantly reached out to ever broader domains, as if they tended to cover the entire social body (FOUCAULT, [6] p. 165). Foucault is deeply interested in analyzing the micro powers that permeate individuals’ lives and their small, almost imperceptible, repetitive habits, which systematically shape bodies and behaviors. Thus, throughout modernity, the body became an object of investment. The body holds a symbolic place in the construction of subjectivity and sociability. History has provided us with different ways of thinking about and relating to the body, and body matters are influenced socially, culturally, politically, and scientifically.

In this context, it is helpful to understand Victor Ferreira’s [7] definition of the body. In a review of the body’s conceptual journey, the social sciences have developed the concept of corporeality, so the body has taken on a role as a social construction situated within time and space. More than the body in its physical reality, we will first consider corporeality. Let us situate what we are referring to with the term corporality or, using a synonym, corporeality. The sociology of the body has named as its object of study, not the human organism but corporeality, as a set of symbolic manifestations of bodily existence duly contextualized in historical time and social space (FERREIRA, [7] p. 2182). The body takes on countless perspectives in this perspective, not equating to a single view but involving social, economic, and cultural discourses. Therefore, besides involving an objective issue related to a physical nature, the human body comprises parts that reflect different styles and genders. When we conceptualize the “body,” we directly connect with the biological as an undeniable living organism. However, other attributions are determined by the social environment and linked to established relationships.

In corporeality, the body takes on dimensions that exhibit a particular set of manifestations symbolic of a bodily existence. Thus, it can be accurately located in both space and historical time. Ferreira states that: Suppose we understand corporeality as the set of concrete properties of the body as a social being. In that case, we can say that a given society simultaneously defines a particular space of corporeality (i.e., several possible bodies formed by rules of convenience in the presentation and management of the body) and a certain modal corporeality (i.e., a specific set of valued properties) (p. 2187).

Consequently, corporeality involves conceptions, judgments, and historical changes. However, it is also helpful to understand that the concepts of care and body, as discussed by Michel Foucault (1976) regarding self-care, point to issues related to the dimension of care that consists of a set of rules of existence. Understanding that the body is something full of meaning and socially assigned names will determine what is accepted. The mechanisms that determine bodily notions gain momentum and construct subjectivities within these discourses, which are a form of social control. Self-care involves using the body as a tool for care-the most subjective dimension of the human being-in how the individual relates to the world and themselves, making a full life possible.

With this theme of the care of the self, we have then, if you like, an early philosophical formulation, appearing clearly in the fifth century B.C., of a notion which permeates all Greek, Hellenistic, and Roman philosophy, as well as Christian spirituality, up to the fourth and fifth centuries A.D. In short, with this notion of epimeleia heautou we have a body of work defining a way of being, a standpoint, forms of reflection, and practices which make it an extremely important phenomenon not just in the history of representations, notions, or theories, but in the history of subjectivity itself or, if you like, in the history of practices of subjectivity [8]. There is work in “Know thyself,” which is an abstract, philosophical, and rational question. It moves on to a more practical, experiential aspect: self-care; care is permanent, linked to physical health, sleep, food, and the soul’s health. In the context of the care of the self, exercising this power over the body rationally produces well-being, and the body becomes the object of work to achieve a life of greater satisfaction and health. Foucault argues that corporeality is not mere existence but the construction of individual and social modes of existence. Each body is exposed to a set of rules to exist and is built through techniques and ideas to reach its fullness. It is a kind of care that idealizes individual well-being and that of others, in which each individual takes care of themselves, as an ethical principle of permanence.

This principle leads us to permanent control over bodily desires. Individuals should not simply let themselves be carried away by impulses, and the inner nature cannot control the human mind. Thus, self-care reinforces the idea that people should exercise control over the body’s deepest desires by developing logical and rational methods of knowing and training oneself. From this ethnographic perspective, the dimension of body control led us to investigate how the individuals who frequent the gym represent themselves and how others represent them. We observed that the forms of representation function as a kind of mirror, in which the practitioner projects the image of the desired body, often reflected in practitioners who have a body considered ideal, either in the gym or through influencers on social media.

According to the informants, when they refer to the process of training, eating, and other sports practices, after a certain period, the bodybuilder will not only strengthen his muscles but will also reach a point where the body is being “sculpted.” In other words, it will take on the ideal shapes that will define the body, making it attractive and masculine, with a particular physique considered that of a handsome, desirable, and healthy man. Thus, the body is essential when it produces harmony in the human senses, ensuring intercommunication between them. This leads to the perception of ideal beauty on the body sculpted by daily work in the gym. Thus, “the presence of the body is full and immediate, and the body is capable of intellection; conscious perception inherits from bodily intellection the impression of bodily fullness” [9].

Regarding the body, the legacy of Marcel Mauss [10] and his classic study of body techniques is undeniable. For him, all bodily expression is learned, which can be understood in his concern to demonstrate the interdependence between the physical, psychosocial, and social domains. Mauss [10] and Van Gennep [11] show that the body techniques correspond to sociocultural mappings of time and space. Mauss argues that the body is the original tool humans use to shape their world and the original substance from which the human world is shaped. The famous essay on body techniques addresses how the body is the raw material that culture shapes and inscribes to create social differences. In other words, the human body can never be found in any supposed “natural state.”

More recently, Le Breton [12] carried out a detailed study dedicated to “understanding human corporeality as a social and cultural phenomenon, a symbolic motif, the object of representations and imaginaries” (p. 7). The author states that the body takes shape as it establishes the social and cultural logic it propagates. Thus, we understand the body as the semantic vector that mediates and constructs human beings’ relationships with the world, demonstrating that every human existence is a bodily existence.

Goldemberg [13] challenges the role of the body as an essential form of physical, symbolic, and social capital, appearing as distinctive features in forming identity. For the author, the body can be an insignia (or emblem) of one’s efforts to control, imprison and domesticate it in order to achieve the ideal body, as appears in the reports ahead; the body can also be a fashion icon (or designer label), which symbolizes the superiority of those who possess it; or even as a prize (medal), deservedly earned by those who were able to achieve a more civilized physique through hard work and sacrifice. It can be said that in Brazil, the body is a capital, maybe the most desired one by the urban middle class and also by lower strata, which perceive the body as a fundamental vehicle for social ascension and also an essential form of capital in the job, spousal, and erotic markets. (p. 543).

In this sense, Goldemberg’s study aims to understand the role of the body in Brazilian culture and the formation of national identity, both in literature and the current phenomenon of cultural industry production, but always as an ideal product of collective effort. Thus, the body as an ideal product is not merely individual but produced collectively. It is the effect of one body on another produced through encounters. These encounters reconfigure the body, deriving a mode of existence from these relationships. It has to do with the social process; the individual’s relationship with friends, family, and the community will produce this way of existing, reproduced within the gym, connecting people in practice to common goals. The social context sets parameters for what should be considered beautiful and healthy, and in this process, people think of a body that is neither entirely personal nor strictly social. The body is a subjective invention based on the statements, perceptions, and representations of individuals and the community, structured symbolically according to gender, sex, age, and social class.

According to the interviewees, shaping the body is the aim of the gym work, but this process takes time. First, we must eliminate fat mass and gradually replace it with muscle mass. Moreover, it is the materialization of a hypertrophied body. The hypertrophy desired by these informants is perceived as fundamental since it is responsible for the visible growth of the body’s muscles. This results from a physical demand in which the body is subjected to an exercise load, producing stimuli that will act directly on the physiological tissue.

In their speeches, the subjects reveal their desire to build their bodies and indicate an ideal body to be achieved. Some even cite references to bodies that are desirable to them: For me, the body has to be well-shaped. If you go to the gym, you have to train hard to get a six-pack; those ripped bellies, you know, get really strong. (L, 22 years old). I’m not sure; I think this body thing is a bit relative. If you’re healthy with your body, you’re fine. But I want to develop my body more; little by little, I’m sculpting my muscles. It takes time, but it will happen. (Re, 23 years old). Ah, I have an idea of the body I want to have. I don’t want anything too surreal; I just want to be a bit stronger, with a more structured body. (R, 30 years old).

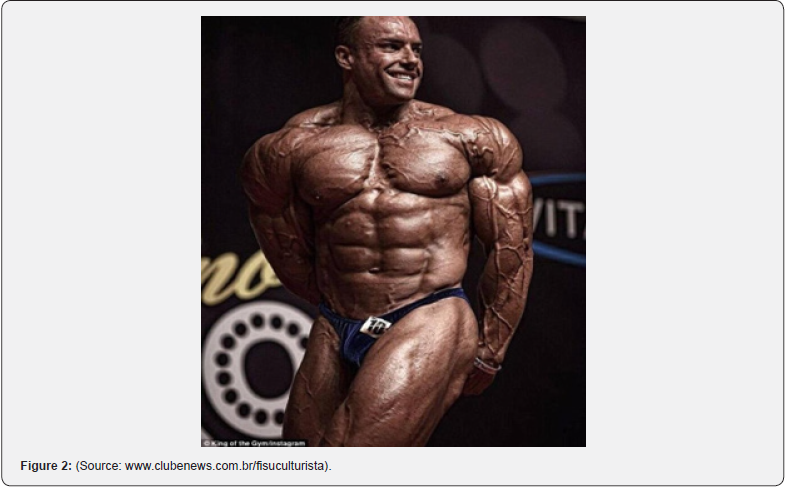

Well, for me, the body has to have certain characteristics, you know, the body has to be very muscular. You have to work on your abdomen a lot to get shredded (V, 25 years old). Several points illustrate the concept of corporeality that the subject wishes to fit into, so we outlined the categories of words used during the conversations with the participants who were willing to answer the questions. The body must have specific characteristics, such as being strong, muscular, resistant, ripped, and jacked; in other words, it is a sculptural body, which we can see in the images they have shown taken from social media (Figures 1 & 2).

Image two represents the body of Josh Lenartowicz, a bodybuilder from Melbourne, Australia. His unusual physique requires a life devoted exclusively to body care and maintenance. The informants refer to an aesthetic ideal of the body, which constitutes an essential platform for interpreting their relationships with their bodies. The image of the body that the individual forges or the uses given to the body makes aesthetic appearance a regulating element in bodily beauty. The desire to beautify the environment in which life takes place responds to an urgent need to channel very particular experiences with the world. Unsurprisingly, human beings have always captured the emotions generated by the environment in artistic works that reproduce them. In other words, through art, they project their feelings of plenitude and perfection, attributing the description of beauty to the objects that reproduce it.

We find exciting contributions as far back as Classical Greece, and it is common (even today) to be associated with terms such as order, proportion, and symmetry. Aristotle [14] formulated one of the essential doctrines of beauty in his work on rhetoric, and it was so widely accepted and developed that, even in our time, it retains its strength. The solidity and argument of the Aristotelian conception lies in its tendency to reveal the objective traits of beauty. His criteria suggest that beauty lies in harmony, proportion, and measure. Physical exercise demands intensity, regularity, and effort from the body so that the muscle is worked and enters a state of hypertrophy, as Foucault describes when talking about La Mettrie’s Machine Man: A body is docile that may be subjected, used, transformed and improved. [...] exercising upon it a subtle coercion, of obtaining holds upon it at the level of the mechanism itself, constraint bears upon the forces rather than upon the signs; the only truly important ceremony is that of exercise. [...] These methods, which made possible the meticulous control of the operations of the body, which assured the constant subjection of its forces and imposed upon them a relation of docility-utility, might be called disciplines [6].

In the gym, during all bodybuilding training, the practitioner adapts their body through certain stimuli for each specific part, working and aligning the muscles of each body limb. As a result, these fundamental processes develop and shape the body of those who choose this lifestyle. The subjects’ statements show the dedication, effort, and discipline required to obtain the desired body, which must be modified to achieve the ideal established in the abovementioned reports. In the statements below, the informants describe what this process is like:

You have to be persistent. I assure you, it’s not straightforward; that’s why some people give up at the beginning. It’s an exhausting process; you have to adapt your body (L, 22 years old).

It’s a sacrifice we have to make, isn’t it? It’s hard; your body isn’t used to making such an effort, so sometimes it gets sore. But as they say, if it hurts, it’s because it’s working (R, 23 years old). Man, sometimes it’s really exhausting, especially when it’s leg day. When you leave the gym and go home, there are times when your leg feels like it will fail (R, 30 years old).

Some days are harder than others, and some workouts can fatigue you, especially if you’re a beginner. But then you get the hang of it, and the training becomes much more enjoyable (Vi, 25 years old).

The gym, especially in the bodybuilding segment, is a process that requires work on the body and its adaptations. In this process, the body changes. The body adapts to perform the exercises better, thus achieving the much-desired hypertrophied body. One of the bodybuilding influencers that our informants watched a lot, and on their recommendation, we visited the YouTube channel of digital fitness influencer Renato Cariani several times. His channel has more than seven million subscribers. His videos have thousands of views. In one of them, Renato Cariani mentions that muscle hypertrophy occurs when people go to the gym to “punish” their muscles, generating micro-injuries. The muscle must be injured in training until it becomes sore. According to him, this is the only way the body understands that there is a need to build bigger and stronger fibers to withstand increasingly heavy training. “Thus, this action generates what we call hypertrophy. Heavy training because if you don’t hurt your fibers, they won’t strengthen themselves.”

Training at the gym requires dedication to caring for the body during routine exercise. Thus, throughout the training, the exercise routine is planned according to weight, height, and the objectives set at each stage:

“I train in four divisions. First, I usually train the chest and shoulder. Then I do the whole leg part, working the back of the thigh and the quadriceps. I train the back and the back of the shoulder. Then I take a rest day and do biceps, triceps, and forearms. Then you repeat the same schedule, with a rest day” (Vi, 25 years old).

“My workouts are simple; I divide them into legs, back and shoulders, chest, and abs. Whenever I need it, there’s an instructor in the gym who helps me and gives me tips on how to do it the right way.” (R, 30 years old).

“I divide my workouts according to each muscle group. So, every day, I work on one part of my body. One day it’s legs, the next chest, the next back, the next biceps and triceps.” (Re, 23 years old).

“I divide it into three parts: chest, triceps, and abs; Thighs and calves; and back, trapezius, and biceps. Each day, I do a series of exercises for each muscle group” (L, 22 years old).

From the subjects’ descriptions, the workout is divided into a series of repetitions, several repetitions per exercise, followed by a rest interval. The number of sets depends on the number of exercises, the muscle groups in question, the stage of training the student is in, and the type of strength. It includes low-repetition, medium-repetition, and high-repetition sets.

In this way, training involves using a certain weight and increasing the number of sets until reaching the maximum the body can lift. When it does not represent maximum body effort, the practitioner should increase the weight and decrease the number of repetitions. Each time this happens, you should restart training by increasing the volume and continuously decreasing the number of sets. Training evolves when there is a constant increase in the work done.

According to the reports, one of the most critical dimensions of organizing time within bodybuilding practices involves using it as exhaustively and efficiently as possible. The first representation, where time is regarded as entirely useful, underlies the meticulous utilization of each moment, particularly in organizing routines into series and repetitions. Series is the number of times different lifts or bodybuilding exercises can be repeated. At the same time, repetitions (which comprise each set) are the number of times an exercise or lift must be performed. The structure of the workout routine in sets and repetitions depends on the goals the practitioner is pursuing over time. Accordingly, if pursuing muscular hypertrophy training, the number of repetitions per set will be low compared to muscular endurance work. This differentiated and meticulous use of time by objectives responds to a rationally regulated order in which bodybuilders train differently to incorporate the technical gesture effectively. The correct design of the exercise will depend on the correct overall disposition of the disciplined body as a condition of efficiency for maximum use of the movements over the training period.

In the ongoing pursuit of refining technical and postural gestures, as represented in exercise routines, it is necessary to emphasize again the importance that machines hold in the anatomic-chronological constitution of the body. This intricate network of devices dictates the breakdown of specific movements targeting particular and detailed parts of the human body, thereby defining the duration and scope of the exercise. This economy of movement, facilitated by mechanized supports, imposes a continuous tension on selectively targeted muscle zones, necessitating the sustained engagement of the trainee’s body.

In this sense, the bodybuilding apparatus will no longer be an exclusive device of the disciplinary space. However, it will also constitute an element of great importance for the organization of planned and rationally programmed time. Based on the above, we can say that the machines, as well as the bodybuilding routines, will bring about the constitution of organic individualities [6], in which they will try to extract more useful movements from increasingly docile bodies.

In addition to the more efficient and meticulous use of time in movement, based on a correct body disposition promoted by the rigorous planning of the routine and the machine, the incorporation of the technical gesture also brings the need to avoid various types of injury. Lifting weights can cause chronic problems in the lumbar region and the neck, so discursive and non-discursive devices inside gyms (leather belts that fix the back in the correct position) protect it from any wrong position. These body constructions symbolize a central element within bodybuilding practices regarding the body disposition of practitioners. In a series of evolutionary discourses, upright posture is of great importance, serving as a synonym for selfcontrol and vitality. What we mean is that the “medical” care of the back to avoid injuries and promote efficient exercise performance underlies postural representations that respond to a specific socio-historical order, in which systematic exercise and a good diet are the basis for representing the idea of a healthy, youthful body.

Berger [15] considers that the pillar underpinning the ideal of the perfect body is mainly individual effort. In the reports, the practitioners understand that even on their own, using equipment, weights, a lot of weight training, food, and chemicals, they can sculpt the desired body that is so publicized and reinforced in the community. In other words, the subject does not have to and should not conform to their natural body since, with their efforts, they can correct what does not correspond to the cultural standards of their time and place. For Berger, these notions of the body are part of today’s widespread ideological system. Through this information, the subjects believe they can choose the body defined as desirable. “You can become the person you dream of being, bodybuilders said. You can defy both nurture and nature and transform yourself.” [16].

The dominant idea sold to bodybuilding enthusiasts is that the individual, he and he alone, is the one who will be accountable to the critical and hierarchical gaze of his peers, in addition to submitting to the scrutiny of the tape measure, the scales, and the mirror in a process that demands ascetic, rational, and individualistic conduct from him. What is more, as well as being the product of individual effort, it involves conquering a body that only he or she will have and, subsequently, the physical form as a vehicle for affirming status, conquering sexual partners on the same aesthetic level, and social insertion. Goldenberg [13] also points out that to achieve the ideal shape and expose your body without embarrassment, you must invest in willpower and selfdiscipline, as reinforced by the collective imaginary represented today by fitness influencers such as Cariani (mentioned above), Paulo Muzzi, and others. It is as if the possibility of building an ideal body, with the help of the technologies available in fitness equipment, food, and dietary supplements, could merge with the construction of destiny, a work of body art meticulously sculpted in every muscle.

The construction of the ideal body also involves motivations. Given the necessity of daily practice to obtain benefits, motivation for adherence and persistence in practice are considered. This consideration relies on factors related to intrinsic motivation, namely, personal motivation to engage in a specific activity, such as pleasure and personal satisfaction, and extrinsic factors related to the environment in which the individual performs the activity. It is necessary to understand the different types of motivation that lead people to engage in sports and physical exercise [17-19].

In conversations with the subjects of this research, we were able to delve deeper into this aspect and obtain some valuable information to understand how the subjects resignify their bodies through exercise practices and how they create the necessary motivations for regular activities and diets to obtain the desired body. What motivates people to come to the gym should be understood as a projection into the future of what they want to achieve. This projection gives us the first guideline regarding the development of motivation as a constant variable in their lives. Anyone who takes up bodybuilding needs an initial reason to start an exercise routine; this willingness must be reiterated daily.

Among the reasons why young people go to the gym, we identified three as the most recurrent: health, aesthetics, and getting rid of the stress of work, which are often interspersed. The goals refer to a future projection and are related to the changes they intend to make or the physical aspects they intend to maintain after deciding to take up the activity. A clear example of this is the changes in mood and enthusiasm, the possibility of breakthroughs and gaining muscle mass, and great opportunities to redouble your commitment and transform your body into a mold that you want to sculpt:

People said I was too skinny. I wanted to see if I could put on some weight; sometimes, a few pounds are good for you! (R, 30 years old).

At first, I joined the gym because of the staff, but then I started seeing results. You know, my body started to develop, but then I continued because of my physique (Re, 23 years old).

The truth is that I joined for the physique itself. I wanted to be very strong, with much muscle. (L, 22 years old).

It’s just that I need to bulk up; it’s tough, so I’m aligning my diet with weight training. (Vi, 25 years old).

From our experience and contact with the field, among the reasons why many of them have come are the health care provided through medical recommendations and the good climate that exists within the facilities. There, they establish relationships of companionship and friendship that do not necessarily transcend the place’s walls. Similarly, regarding the organization of spaces within the facilities, we have always been struck by the fact that there are no conflicts regarding the occupation of the equipment. As described above, there is a disproportion in the ratio of equipment to users during specific shifts, especially in the early evening, which makes it difficult for people to move around freely in the area and to carry out their exercise routine. In this sense, there is a non-explicit organization among the participants regarding the location and occupation of the equipment.

We could further denote that learning about what type of routine to follow and how is not solely imparted by coaches to the younger ones but amongst themselves and drawing from theory and their own experience in the field. The training work at the gym is based on the repetition of routines, sets, and exercises determined in their case by the coach. Observing, the learning of routines occurs more through peer imitation than instructor intervention, where the less experienced gradually appropriate the correct way to perform the exercises. Notably, this cannot be conveyed orally by the coach or transmitted manually, but rather, the repetition of exercises ensures the appropriation and refinement of technique.

The attendees understand that the same equipment can be used in different ways, depending on the trainer’s creativity, and that the best way to organize the training is to take ownership of the knowledge and the different ways of doing the routine and invent new ones. However, this can only be achieved with time, effort, and dedication because the ability to grasp carries an almost disciplinary and ascetic attitude, which must be considered a pillar by those who train. In this way, and only in this way, the person who starts training can gradually stop being inexperienced and develop new strategies in their routine.

Final remarks

This ethnographic research is backed up by discursive records of young people aged between 22 and 30 on corporeality. It sought to record and discuss the motivation for taking up bodybuilding and the discipline and training of the body. Thus, it showed the sharing of perceptions and body representations about the ideal body, the initial dissatisfaction with one’s body, and the routine training to polish the sculptural body, especially the one represented in the speeches and images produced by our collaborators.

In this way, we were able to observe, through the recurrent use of body maintenance equipment and various exercise sequences, how these young people construct their ideal body, which must meet certain expectations: a strong, muscular, defined body that tends to stand out and take up a particular place in society because it attracts attention.

In this sense, in the permanent quest to achieve the ideal body, a correct technical and postural gesture, represented in the exercise routines, adds to the importance that machines represent in the anatomical-chronological constitution of the body in modern times.

Finally, it is essential to consider that within the scope of this article, it was not possible to describe and analyze the dietary routine of weightlifters and their ways of existing beyond the gym environment, such as their network of relationships and modes of dressing to display their bodies under construction or maintenance.

References

- Silva AC, Ferreira J (2019) Rituais de iniciação à dor entre homens na musculação: etnografia de uma academia de giná Saúde Soc. São Paulo 28(2): 160-173.

- Cesaro H (2012) Os “Alquimistas” da vila: masculinidades e práticas corporais de hipertrofia numa academia de Porto Alegre. (111 f.) Dissertação de Mestrado. Programa de Pós-Graduação em Ciências do Movimento Humano. UFRGS.

- Malinowski B (1996) Antropologia. Ática, São Paulo.

- Evans-Pritchard EE (2005) Bruxaria, oráculos e magia entre os Azande. Jorge Zahar Editor, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Elias Norbert (1993) O Processo Civilizador 2: formação do Estado e civilizaçã Editora Schwarcz-Companhia das Letras.

- Foucault M (1987) Vigiar e punir. 25 ed. Vozes, Petrópolis, Brazil.

- Ferreira VS (2013) Resgates sociológicos do corpo: esboço de um percurso conceptual. Análise Social, Lisboa 208(3): 2182-2999.

- Foucault M (210) A hermenêutica do sujeito. São Paulo: WMF Martins Fontes. Ciências Sociais. Vitória: CCHN, UFES, Edição 1(2): 121-160.

- Henriques JC (2008) Significação ontológica da experiência estética: a contribuição de Mikel Dufrenne. Dissertação de Mestrado, Instituto de Filosofia, Artes e Cultura, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, MG.

- Mauss Marcel (2003) As técnicas do corpo. In: Sociologia e antropologia. São Paulo: Casac Naify p. 399-422.

- Gennep AV (2011) Os ritos de passage (2nd edition), Trans. Mariano Ferreira. Vozes, Petró

- Le Breton D (2007) A sociologia do corpo (2nd edition). Vozes, Petrópolis, Brazil.

- Goldemberg M (2011) Gênero, “o Corpo” e “Imitação Prestigiosa” na Cultura Brasileira. Saúde Soc. São Paulo 20(3): 543-553.

- Aristóteles (2007) A retó São Paulo: Rideel. (Coleção biblioteca clássica).

- Berger M (2007) Mídia e espetáculo no culto ao corpo: o corpo miragem. Sinais - Revista Eletrônica de Ciências Sociais. Vitória: CCHN, UFES, Edição 1(2): 121-160.

- Fussel S (1991) Muscle: The Confession of an Unlikely Body-Builders, Poseidddon Press, New York.

- Souza DM, Gabriela FP, Luana W, Roberta MO (2023) Autopercepção dos benefícios e motivações para prática de CrossFit. Rev Fam Ciclos Vida Saúde Contexto Soc 11(3): e7065.

- Daolio J (2020) Da cultura do corpo. Papirus, Campinas.

- Castro AL (2007) Culto ao corpo e sociedade: mídia, estilos de vida e consume (2nd edn). São Paulo: Annablume/Fapesp.