Greenstone Pendants (Muiraquitãs): Spheres of Political Interaction Among The Caribbean, Lower Amazon and Maranhão, Brazil

Alexandre Guida Navarro*

Associate Professor, Federal University of Maranhão, Laboratory of Archaeology, Brazil

Submission: April 01, 2024; Published: April 22, 2024

*Corresponding author: Alexandre Guida Navarro, Associate Professor, Federal University of Maranhão, Laboratory of Archaeology, Av. dos Portugueses 1966, Bacanga, cep.: 65080-805, São Luís, Brazil

How to cite this article: Alexandre Guida Navarro*. Greenstone Pendants (Muiraquitãs): Spheres of Political Interaction Among The Caribbean, Lower Amazon and Maranhão, Brazil. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2024; 13(5): 555873. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2024.13.555873

Abstract

Pendants made of green stone and known as muiraquitãs were made by pre-colonial Amazonian indigenous peoples. Possibly used as jewelry, these artifacts comprised a sphere of political interaction that encompassed the Caribbean, lower Amazon and the Brazilian state of Maranhão. This article discusses these relationships based on three muiraquitãs found in the stilt villages of Maranhã

Keywords: Greenstone; Muiraquitã; Pendant; Jewelry; Spheres of Political Interaction

Introduction: what are muiraquitãs?

Muiraquitãs were rare stones. They are green stone artifacts, with a Batrachian shape and side holes, whose etymology has indigenous Tupi origin, and referring to a bead in the shape of a toad or frog. This article presents three muiraquitãs found in the stilt villages of Maranhão, pre-colonial stilt sites located in the Eastern Amazon. All three specimens were collected in an archaeological context, two of them by Raimundo Lopes at the beginning of the 20th century and another collected in situ by the author of this article in 2014. Although these artifacts are associated with the function of an amulet, it is not known for certain whether they actually had this meaning. However, the existence of side holes suggests its use as a pendant or adornment. More recent studies [1-6] make important contributions to the construction of knowledge about green stones. The making of greenstone artifacts appears to have been a common phenomenon throughout pre-Columbian America and involved spheres of interaction of prestige goods. Olmecs appear to have traded this stone with societies in northern Costa Rica [7]. Among the Mayans, jade was associated with the power of the ruler, being commonly found in royal tombs in the form of beads, necklaces, rings, bracelets and funerary masks, such as the tomb of Pacal, in the city of Palenque, whose set is the stone found at the site weighed a few kilos [8].

Due to its peculiar properties, such as high hardness, intense brightness and green color, it was also associated with the Mesoamerican divine world, being frequently represented in codices [9]. Among the Aztecs, the stone was even represented in the Matrícula de Tributos, a document in which the tlatoani or Aztec emperor recorded all products taxed by the empire, given that the material did not exist in the Valley of Mexico and needed to be imported from the Mayan area [10-12].

In the Amazon, as previously reported, the main production area for muiraquitãs appears to have been the Santarém region, inhabited by the Tapajós indigenous people. Rodrigues [13] comments that these stones were found in the lower Nhamundá. Ferreira [14] mentions the right bank of the Trombetas river. Boomert [1] recognizes three areas of production: 1) the lower Amazon, with the Nhamundá, Trombetas and Tapajós rivers being its area of influence, associated with the Incised Punctate and Polichrome archaeological traditions; 2) northern Suriname, associated with the Kwatta ceramic complex, of the Araquinoid tradition; 3) the Antilles, whose Batrachian specimens are common in the context of the Saladoid tradition. Meirelles and Costa [15] reconsider the origin of some types of Amazonian muiraquitãs, stating that some of them are jade-jadeitic, whose mineral is completely unknown in the Amazon, with a possible source of obtaining the Motágua Valley, in Guatemala. Therefore, although we know little about the production of muiraquitãs, it is undeniable that these rare lithic artifacts appeared as objects of prestige and participated in complex commercial networks, which involved the Amazon and the Caribbean, Central America [1,2,16] and, to a lesser extent, the Andean region, especially among the Muisca or Chibchas, in Colombia [17,18].

The Maranhão Stilt Villages

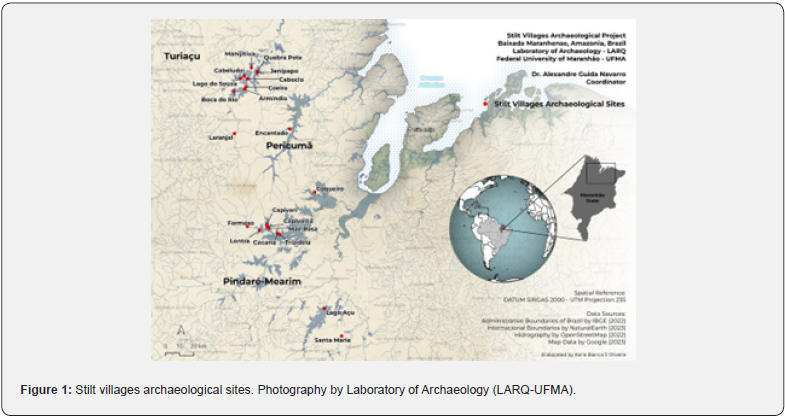

In the 1990s, some Brazilian archaeologists pointed out that stilt villages were the least studied sites in Brazil, which are lake settlements in which houses were built on wooden supports [19,20]. In colonial chronicles, these stilt sites are rarely mentioned, and material remains of similar prehistoric occupations seem to exist only in Maranhão, eastern Amazon (Figure 1). They appear in greater dimensions in the expeditions of Aguirre and Ursúa, carried out through the upper Amazon in 1516, but to this day the supposed pillars have never been found by archaeologists. Some reports can also be found in Vespucci’s writings regarding what is today, Venezuela. The stilt villages are located in the area known as Baixada Maranhão, covering an area of 20 thousand km² within the Legal Amazon, currently with around 500 thousand inhabitants (IBGE Census). It is a very poor territory, with the lowest HDI indexes not only in the State of Maranhão, but also in all of Brazil, whose population lives off traditional agriculture, fishing, small animal husbandry and plant extractivism, especially the babassu coconut.

The main cities in this area are Penalva, Pinheiro, Viana, São Bento and Santa Helena [20]. The stilt sites were built within Pleistocene rivers and lakes, characterized by floodplains that remain flooded from January to June and gradually dry out in the other months of the year [20-22]. Although the type of sociopolitical organization of these people is not yet known, the Amazon floodplain environment may have been conducive to the establishment of complex societies. The measurement of a stearia in 2 km, made by Simões [23], may be evidence of this debate [20]. On the other hand, it is not known who these groups were and what language they spoke. Studies of material culture show artifacts similar to those made by the Karib groups.

The muiraquitã from the Boca do Rio stilt village

The first muiraquitã presented here results from a surface collection in the Boca do Rio stilt village inTuriaçu river at Santa Helena city, in Maranhão state of Brazil. This artifact was carried out by the author of this study in 2014. The muiraquitã from Boca do Rio weighs 5.12 g and presents 2.92 cm in length, 1.81 cm in waist, 1.70 cm in width of the head, 0.90 cm in width of the neck and 0.4 cm in thickness, having similar proportions to that evidenced by the majority of muiraquitãs found in the Amazon [4] (Figure 2).

The features of this artifact allow us to easily recognize the trunk of a frog and possibly a stylized anthropozoomorphic head. The specimen comprises three parts or sections: the head, the trunk and the lower limbs. The head, with Batrachian and human features, is outlined by three sub-horizontal planes. The first of them forms is a horn or crown, with a bipartite shape; then, delimited by grooves that outline the second composition, are the eyes of the muiraquitã, oval and drawn - in high relief - in two quadrangular planes, the ends of which form part of the face of the batrachian, and, finally, the third part is composed of a groove in the piece and a rectangular band, which crosses the piece along its entire longitudinal axis. Another possible reading is that the crown forms the plume of a bird that, seen from perspective and in profile, forms the heads of two birds. The trunk has a triangular shape, with three incisions in the longitudinal direction; On the back of the piece, two side holes appear. The lower limbs are stylized, as is the case in most muiraquitãs, whose iconographic composition is formed by two lateral incisions on each side, with perpendicular lines, which converge in the representation of the rectangular legs.

Mineralogical analyzes by MicroRaman demonstrated that the main mineral constitution of muiraquitã is tremolite/actinolite, therefore equivalent to what is generically known as nephrite [4]. These results were confirmed by XRD analyses, which showed that tremolite-actinolite was mainly the constituent element of the piece, with tremolite being dominant. This mineral composition was also confirmed by chemical analyses, both by XRD and SEM/EDS chemical analyses, making clear the dominance of the tremolite member, since the FeO content is very low. The reddishbrown spots represent residues of clay and iron oxides from the sediments that buried it at the time of the stilt village.

Muiraquitãs from Cajari lake

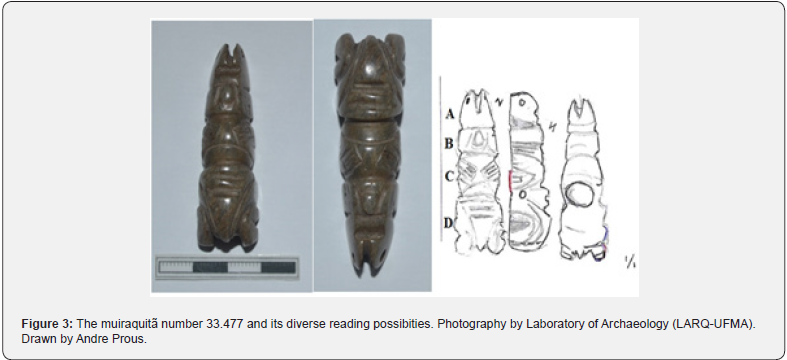

Now we will present the other two muiraquitãs, found by Raimundo Lopes in 1919 in Cajari lake, in the Cacaria stilt village. More specific studies could not be carried out, as the pieces were located in the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro, which, with the 2018 fire, was destroyed. The author of this article and archaeologist André Prous were at the National Museum shortly before it caught fire. The raw material and morphology of muiraquitã number 33.477 is made of a greenish rock (jadeite, nephrite or serpentine) with a more homogeneous color than the other piece (number 33.448) collected by Lopes. No hardness test was attempted (jadeite being harder (6.5 to 7 on the Mohs scale) than the others, with serpentine hardness.

In principle, the general shape of specimen number 33.477 does not seem to evoke a batrachian. In fact, it seems that the author of the sculpture decided to play with shapes to produce a series of ambiguities, making several readings possible, a recurring feature in Amazonian lithic material [24-28]. The existence of two transversal holes - one near one end and the other in the opposite third of the other - seems to reinforce this intention: the object could thus be hung in two ways, proposing two different interpretations, depending on the end chosen to form the upper part.

Placing the piece in frontal view and with volume “A” upwards, this volume can be interpreted as the glans of a phallus. In volume “B”, a central protuberance can be read as a face, but there are no eyes or mouth figured. Volume “C”, in turn, clearly depicts a torso with tridactyl hands arranged obliquely on the chest, fingers down. Block “D”, in turn, obviously represents the lower part of the body, with the two bent legs separated by a large triangle; such a symbol can evoke either a pubis or a thong. Given the characteristic of the very large and strong hind legs, which could enable long jumps, this volume also resembles the abdominal segment of a grasshopper (Figure 3).

If we view the piece in the opposite direction, the upper volume suggests a head of a bird, whose eyes would be represented by the ends of the perforation. Volume “B” would then form a torso, while the bent legs are represented in “C”. Turning the piece so that “D” is in the upper position, “C” becomes a head with side ears, a large triangular nose and a straight closed mouth. “C” represents the torso, on which the tridactyl hands have their fingers pointing upwards. Volume “B” becomes the belly, with the central protuberance representing the sex (Mount of Venus, or penis?), or even a navel.

The piece number 33.448 undoubtedly evokes an anuran (toad, frog or tree frog), being a classic muiraquitã. This piece of green rock presents the classic characteristics of muiraquitãs with its batrachian theme, its dimensions within the average of these artifacts, its triangular shape, absence of front legs. It differs, however, from most in that it does not have eyes or the depression between the protuberances that top these organs. Despite this simplification, it presents a slight pattern that places it within the category of the best quality pieces (Figure 4).

Discussion

Tremolite-actinolite greenstone, the material from which the muiraquitã of Boca do Rio was made, does not exist in the Maranhão state, neither in pre-colonial times nor today. For this reason, the discovery of the artifact in an archaeological context is extremely rare in the archeology of the lowlands of South America. The play highlights debates about social aspects, interethnic interaction and paths beyond regional political borders that involve the prehistoric societies of Central and South America and the Caribbean [6,29,30], as done by recent discussions on extensive spheres of interaction between the Caribbean and the Amazon through studies of ceramic styles, such as Koriabo [31-33].

The indigenous peoples who occupied the Amazon in the pre-colonial period formed complex networks of social interaction. The green stones, many of them representing Batrachian forms, seem to have been a Pan-American element, and their symbolism, generally associated with life, is recurrent throughout the American continent, especially in Mesoamerica, whose greatest source of obtaining them was the Motagua Valley, in Guatemala [34]. Greenstone ornaments, especially pendants, are characteristic of the Isthmus-Antilles region, showing that the connections between Mesoamerica and the Caribbean were much more active than imagined by Paul Kirchhoff, when proposing different cultural areas for the different geographic regions [35,36]. Recent archaeological discoveries show evident interaction between the human groups that inhabited the Antilles and the region of Colombia, covering an area that extends from northwestern Venezuela to the western portion of Honduras [37]. For this author, the year 700 AD corresponded to the peak of interaction between the Caribbean and the area of the Colombian Isthmus, especially in the Huecoid tradition of Puerto Rico and the north of the Antilles.

In fact, it is possible to perceive greater cultural interaction with the distribution of greenstone, shells, tumbagas and other artifacts with regional symbolic significance, whose most recurrent themes are bird-shaped pendants (the most recurrent in the shape of a condor, a typical Andean bird), images of reptiles and Batrachian ornaments. In the highlands and lowlands of South America, this type of material has still been little studied, although it is also recurrent, but on a smaller scale than that of Central America. Rostain [16] associates the manufacture of muiraquitãs with a specialized activity focused on long-distance trade in chiefdom-type societies. This researcher relates the production of green stone to a complex system of exchange between Arauquinoid societies that inhabited the mounds characteristic of the Guyanas prehistory. Given that rocky outcrops are rare in this region, and especially on the coast, the green stones were probably imported.

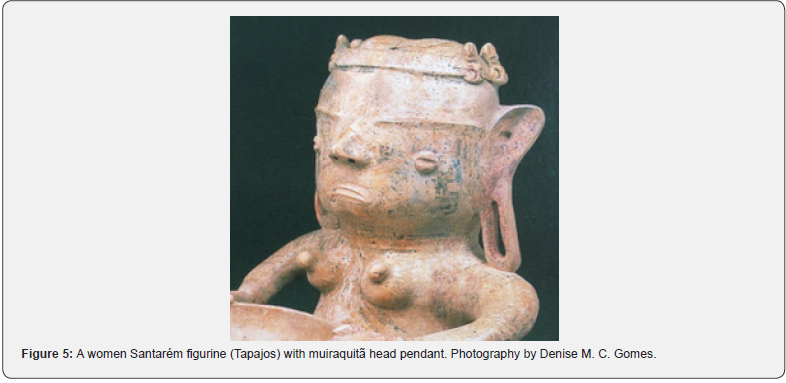

According to Boomert [1], the muiraquitãs corresponded to the main means of interethnic ceremonial exchange in the Guyanas region. In the Kwatta culture, on the coast of present-day Suriname, for example, amulets were made of rhyolite, nephrite, quartz and tremolite, materials that did not exist on the coast, indicating that they were imported from the interior of this region. It is important to highlight that the peak of this culture corresponds to the period of construction of the Boca do Rio stilt village, ca. 850 A.D. Other studies, such as that of Wassén [38], seek to associate green stones with luxury and prestige material, which were exchanged between the chiefs of different villages with the aim of consolidating political alliances through marriage or providing peace in times of war. Other interpretations on the use of muiraquitã are in Gomes [28], which presents a figurine representing a woman with muiraquitãs sewn onto a band, used as a head adornment, in addition to numerous tapajonic figurines (Santarem culture), which show the use of frog-shaped pendants (Figure 5). The same can be said in relation to figurine references in the circum-Caribbean area, studied by Antczak, M. and Antczak, A. [39], and in the Amazon, documented by Roosevelt [40] and Schaan [41,42]. A probable religious function can also be discussed: recently Gomes [28] proposes that a regional sphere was formed in Santarem based on exchanges and ritual (Figure 6). Rostain [16] thinks that in the Guyanas region there was a large chiefdom bringing together people of Arawak origin specialized in particular activities, each of them controlling this activity and exporting their products (material and immaterial) to other centers of neighboring groups.

In this case, the Hertenrits culture fulfilled the function of elaborating the religious practices of the chiefdom; Barbakoeba was dedicated to cultivating elevated fields; and Kwatta manufactured green stone amulets which, according to the archaeologist, were exported to the island of Marajó, at the mouth of the Amazon River. From this discussion on spheres of interaction, we propose the existence of social relations between political entities, understood as independent or autonomous societies, with a similar level of political organization (on a smaller or larger scale), within a similar geographic region, i.e., peer polity, which used symbolisms shared and understood within spheres of social interaction [43,44]. Peer polity occurs in several forms, the most recurrent being symbolic convergence, which emphasizes that the spheres of interaction lead societies to converge, that is, they share goods and ideas, as is the case, for example, with ritual paraphernalia, iconography. This convergence would occur mainly through ceremonial exchanges of valuable objects, with greater emphasis on the exchange of prestige goods between the elites of these spheres.

From these ethno-historical studies, some archaeologists created their interpretations about the use and function of muiraquitãs. For Rostain [16], the muiraquitãs produced in the Guyanas were artifacts of ceremonial and interethnic exchange between tribal chiefs with the function of performing marriage or promoting peace. For Boomert [1], green stones were objects of prestige and luxury in a ritual context, traded on long-distance routes between the Caribbean and the Amazon, exchanged between families in these regions. Barata [45,46] mentions that muiraquitãs were found inside funerary urns, suggesting that they were necklaces and giving status to that person. For Wassén [38], green stones representing anurans are the main marriage transaction between indigenous chiefdoms. Roosevelt [40] and Gomes [27] point out that muiraquitãs were feminine adornments to tie up their hair. For Schaan [41], muiraquitãs were jewelry used in ceremonial exchanges between indigenous leaders.

Conclusion

The comparative mineralogical, symbolic and archaeological data between the muiraquitãs of the region of Santarém, Marajó and those of the estearias corroborate the existence of exchange networks already documented between the Lower Amazon, the Guyanas and the Antilles [47]. What is unprecedented here is that these networks extended to the Maranhão estuary. Although political relations are still the least studied topic in Brazilian Amazon Archaeology, these exchange networks could involve spheres of interaction of the type peer polity, that is, political entities that based their power on powerful artifacts, which gave prestige and power to ruling individuals. Unlike what Boomert [1] postulated when considering that, as the muiraquitãs move away from their source of production, that is, the Lower Amazon region on the Tapajós and Trombetas Nhamundá rivers, they lose their quality and design, being less elaborated, the specimens found in the stelaria have a quality equal to, if not greater than, that of the classical area mentioned. While a loss of quality in the “periphery” could be interpreted as the result of a local imitation of exogenous parts with restricted access, the Maranhão case would point to direct long-distance relationships.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank my colleagues who collaborated in different ways, Andre Prous, Marcondes Lima da Costa, João Costa Gouveia Neto, Abrahão Sanderson Nunes Fernandes, Rômulo Simões Angélica and Suyanne Santos Rodrigues. Also, I would to thank to the Foundation for Support to Research and Scientific and Technological Development of the State of Maranhão (FAPEMA) and the National Council for the Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq) for the funding (Process number 303620/2021-8).

References

- Boomert Arie (1987) Gifts of the Amazon: “green stone” pendants and beads as item of ceremonial exchange in Amazonia and the Caribbean. Antropologica, Caracas 67(1):33-54.

- Costa Marcondes L, Silva Anna Cristina Resque L; Angélica Rômulo Simões (2022a) Muyrakytã ou Muiraquitã, um talismã arqueológico em jade procedente da Amazônia: uma revisão histórica e considerações antropogeoló Acta Amazonica, Manaus 32(3): 467-490.

- Costa Marcondes L; Silva Anna Cristina Resque L; Angélica Rômulo Simões; Pöllmann H, Schuckmann W (2022b) Muyrakytã ou Muiraquitã: um talismã arqueológico em jade procedente da Amazônia: aspectos físicos, mineralogia, composição química e sua importância etnogeoló Acta Amazonica, Manaus 32(3): 431-448.

- Navarro Alexandre G, Costa Marcondes L, Silva Abrahão SNF, Angélica Rômulo S, Rodrigues Suyanne S, et al. (2017) O muiraquitã da estearia da Boca do Rio, Santa Helena, Maranhão: estudo arqueológico, mineralógico e simbó Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas 12(3): 869-894.

- Navarro Alexandre G, Prous A (2020) Os muiraquitãs das estearias do lago Cajari depositados no Museu Nacional (RJ): estudo tecnológico, simbólico e de circulação de bens de prestí Revista da Sociedade de Arqueologia Brasileira 33(2): 66-91.

- Navarro Alexandre G, Rostain Stéphen (2023) Pre-Columbian Amazon Jewelry. Glob J Arch and Anthropol 13: 1-3.

- Fernández Sánchez Pablo (2010) Introducción al estudio de la producción de jade en el mundo olmeca. Arqueología y Territorio, Granada 7: 93-104.

- Navarro Alexandre G (2007) Las serpientes emplumadas de Chichén Itzá: distribución espacial e imaginerí Cidade do México: Unam. Tese de doutorado.

- França LM (2010) El jade y las piedras verdes em Teotihuacan, Mé Revista do Museu de Arqueologia e Etnologia 20: 327-344.

- Taube Karl (1992) The Major Gods of Ancient Yucatan. Dumbarton Oaks Research Library and Collection, Washington, DC.

- Taube K, Hruby Z, Romero L (2004) Fuentes de jadeíta y antiguos talleres: un reconocimiento arqueológico en el curso superior del río El Tambor, Guatemala. Relatório Famsi.

- Rochette ET (2007) Investigación sobre producción de bienes de prestigio de jade en el valle medio del Motágua, Guatemala. México: Revista de Arqueología de México1: 35.

- Rodrigues BO (1899) Muyrakytã e os ídolos simbó Estudo da origem asiática da civilização do Amazonas nos tempos pré-históricos. Imprensa Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Ferreira Francisco Ignacio (1885) Diccionario geographico das Minas do Brazil. Imprensa Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Meirelles Anna CR, Costa Marcondes L (2012) Mineralogy and Chemistry of the green stone artifacts (muiraquitãs) of the museums of the Brazilian State of Pará. REM: Revista Escola de Minas, Ouro Preto 65(1): 59-64.

- Rostain Stéphen (2010) Cacicazgos guyanenses: mito o realidad? In: Pereira Edith; Guapindaia Vera (Org.). Arqueologia amazô Belém: Mpeg/Iphan/Secult 1: 167-192.

- Krickeberg Walter (1971) Mitos y leyendas de los Aztecas, Incas, Mayas y Muiscas. México: Fondo de Cultura Econó

- Bourget Steve, Jones Kimberly L (2008) The art and archaeology of the Moche: an ancient Andean society of the Peruvian North Coast. University of Texas Press, Austin, US.

- Lopes Raimundo (1924) A civilização lacustre do Brasil. Boletim do Museu Nacional 1(2): 87-109.

- Navarro Alexandre G (2018) New evidente for the late first millennium AD stilt-house settlements in Eastern Amazonia. Antiquity 92(366): 1586-1603.

- Franco José Raimundo Campelo (2012) Segredos do rio Maracu: a hidrogeografia dos lagos de reentrâncias da Baixada Maranhense, Sítio Ramsar, Brasil. São Luís: Edufma.

- Ab’saber Aziz Nacib (2006) Brasil: paisagens de exceção: o litoral e o pantanal mato-grossense: patrimônios bá São Paulo: Ateliê Editorial.

- Simões Mario F (1981) As pesquisas arqueológicas no Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi (1870-1981). Acta Amazonica, Manaus 11(Suppl 1): 149-165.

- Prous André (1992) Arqueologia brasileira. UnB, Brasí

- Aires Da Fonseca João (2000) As estatuetas líticas do Baixo Amazonas. In: Pereira, Edithe; Guapindaia, Vera. (org.). Arqueologia amazônica 1. Belém: Mpeg/Iphan/Secult p. 235-257.

- Porro Antonio (2010) Arte e simbolismo xamânico na Amazô Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi. Ciências Humanas 5(1): 129-144.

- Gomes Denise MC (2012) O perspectivismo ameríndio e a ideia de uma estética americana. Boletim do Museu Paraense Emílio Goeldi 7(1): 133-159.

- Gomes Denise MC (2016) Politics and Ritual in Large Villages in Santarém, Lower Amazon, Brazil. Cambridge Archa J (27): 1-19.

- Watters DR, Scaglion Richard (1994) Beads and pendants from Trants, Montserrat: implications for the prehistoric lapidary industry of the Caribbean. Annals of Carnegie Museum, Pittsburgh 63(3): 215-237.

- Knippenberg Sebastian (2007) Stone artifact production and exchange among the Lesser Antilles. Leiden: Leiden University Press.

- Boomert Arie (2004) Koriabo and the Polychrome Tradition: The Late Prehistoric era between the Orinoco and Amazon mouths. In: DELPUECH, André; HOFMAN, Corinne (Ed.). Late ceramic age societies in the Eastern Caribbean. London: Archaeopress, p. 251-266.

- Van Den Bel Martijn (2010) A Koriabo site on the Lower Maroni River: results of the preventive archaeological excavation at Crique Sparouine, French Guiana. In: Pereira Edithe, Guapindaia Vera (Ed.). Arqueologia amazô Belém: Mpeg, Iphan, Secult, 1: 61-94.

- Keegan William F, Hofman Corinne L (2017) The Caribbean before Columbus. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- Sharer Robert J (2003) La civilización maya. México: Fondo de Cultura Econó

- Kirchhoff Paul (1943) Mesoamérica: sus límites geográficos, composición étnica y caracteres culturales. México: Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia/Sociedad de Alumnos, (Tlatoani. Suplemento, 3) p. 1-20.

- Domínguez Lourdes S, Funari Pedro Paulo A (2012) O Caribe intangí In: Karnal Leandro, Domínguez Lourdes S, Kalil Luis Guilherme A, Fernandes Luis Estevam de O. Cronistas do Caribe. Campinas: UNICAMP/Instituto de Filosofia e Ciências Humanas p. 11-18.

- Rodríguez Ramos R (2013) Isthmo-Antillean Engagements. In: Keegan William F, Hofman Corinne L, Rodríguez Ramos R (Ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Caribbean Archaeology. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, p. 155-170.

- Wassén Henry (1934) The frog-motive among the South American Indians: ornamental studies. Anthropos, Barcelona 29(3): 319-370.

- Antczak María M, Antczak Andrzej (2006) Los ídolos de las islas prometidas: Arqueología prehispaníca del Archipiélago de Los Roques. Universidad Simón Bolívar/Editorial Equinoccio, Caracas, Venezuela's.

- Roosevelt (1988) Anna Curtenius. Interpreting certain female images in prehistoric art. In: Miller Virginia E (Ed.). The role of gender in precolumbian art and architecture. Lanham MD: University Press of America p. 1-34.

- Schaan Denise P (2009) Cultura marajoara. Edição trilíngue: português, espanhol, inglê São Paulo: Senac.

- Schaan Denise P (2003) A ceramista, seu pote e sua tanga: identidade e papéis sociais em um cacicado marajoara. Revista de Arqueologia, São Paulo 16(1): 31-45.

- Renfrew Colin, Bahn Paul (2004) Arqueologí Teorías, métodos y práctica. Madri: Akal, 2004.

- Renfrew Colin, Cherry John F (1986) Peer polity interaction and socio-political change. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Barata Frederico (1954) O muiraquitã e as contas dos Tapajó. Revista do Museu Paulista 8: 229- 252.

- Barata Frederico (1952) Artes plásticas no Brasil. Arqueologia. Larraigoti, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil.

- Instituto Brasileiro De Geografia e Estatística (IBGE) (2010) Censo Demográfico de 2010. Características da população e dos domicí Resultado do Universo.