Enhancing Visualization of Roman Aqueducts and Water Canalization in Volubilis, Morocco: A Study Using UAV Photogrammetry and Field Observations

Ahmed Lachhab1* and El Mehdi Benyassine2

1Susquehanna University, Earth and Environmental Sciences, 514 University Ave, Selinsgrove, PA 17870, USA

2National Institute of Archaeological Sciences and Heritage, Ave Allal El Fassi, Hay Riad, BP. 6828, Rabat, Morocco

Submission: February 10, 2024; Published: April 2, 2024

*Corresponding author: Ahmed Lachhab, Susquehanna University, Earth and Environmental Sciences, 514 University Ave, Selinsgrove, PA 17870, USA

How to cite this article: Ahmed Lachhab* and El Mehdi Benyassine. Enhancing Visualization of Roman Aqueducts and Water Canalization in Volubilis, Morocco: A Study Using UAV Photogrammetry and Field Observations. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2024; 13(5): 555872. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2024.13.555872

Abstract

This study investigates the application of Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAVs) photogrammetry alongside field observations to enhance the visualization of aqueduct and water canalization systems in Volubilis, Morocco, a UNESCO World Heritage site. Focused on the Roman period, the research explores the aqueducts’ role in supplying water to diverse structures, including private houses, cisterns, public fountains, baths, official buildings, and public latrines. The city’s growth from the Mauretanian period to its establishment as a Roman municipality in 42 A.D. witnessed the development of significant structures and an intricate water management system. The aqueducts sourced water from the springs of Fertassa and Laksar, utilizing the topography and gravity to direct water from upland to Volubilis. In contrast to previous studies relying on surface observations and/or geophysical methods, the research herein study integrates both photogrammetry and field observation techniques. Orthomosaics maps, digital 3D models, and Digital Elevation Models (DEMs) obtained from Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) surveys of Volubilis were used to illustrate the aqueducts’ orientation and direction of canalization within the city. The complex network of water systems within houses is exemplified by the House of Venus and the House of Orpheus. The study identifies three main categories: surface and subsurface canals, intra-wall conduits made of ceramic or lead, and/or a combination of both. Despite gaps resulting from the loss or collapse of entire structures, the study successfully connects water conduits from aqueducts to various locations in Volubilis. The DEM underscores the crucial role of gravity in water distribution, prompting inquiries into the mechanisms involved and suggesting potential employment of surface, siphoning, over-wall canalization, and/or a combination thereof. Photogrammetric analysis, coupled with meticulous field observations, contributes to the reconstruction of a comprehensive conceptual model of the hydraulic system of Volubilis. The latter showcases elaborate water basins, latrines, baths, and fountains, with water directed through a vertical ceramic pipe fed by underground channels originating from the main aqueduct crossing the center of Volubilis. This research provides valuable insights into Roman water supply and infrastructure management, highlighting the seamless integration of photogrammetry, field observations, and historical evidence. The findings significantly contribute to our understanding of ancient aqueduct systems and their role in sustaining urban life in the Roman city of Volubilis.

Keywords: Roman Aqueducts; Heritage; Historical Evidence; Photogrammetry; Volubilis

Introduction

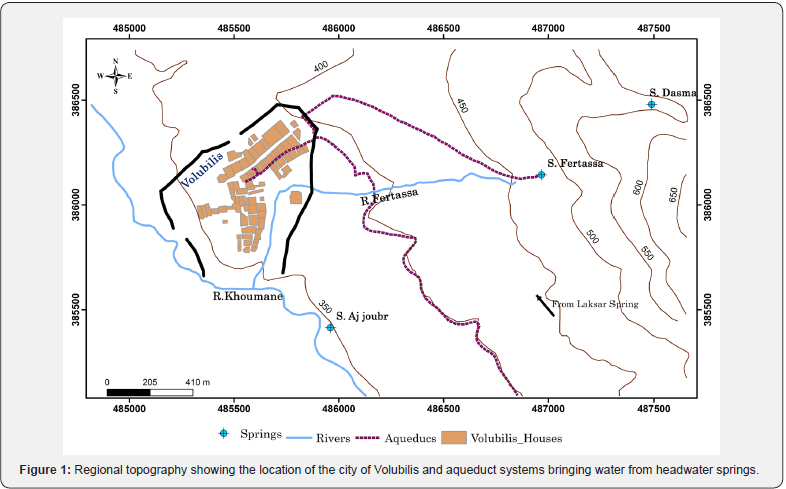

This study explores the application of Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) photogrammetry in conjunction with field observations to enhance the visualization of water distribution systems and their role in supplying water to private houses, cisterns, public fountains, public baths, official buildings, and public latrines during the Roman presence in Volubilis, Morocco. Volubilis is an archaeological UNESCO World Heritage site since 1997 located 26 km North of Meknes. It is considered one of Morocco’s most significant archaeological sites. Volubilis witnessed its initial occupancy during the Mauretanian period (late 2nd -1st century B.C.) and became a Roman municipality by 42 A.D., with subsequent expansion to the north, northeast, and west of the city [1]. Notable buildings such as the forum, luxurious residential houses, additional aqueducts, and public baths were constructed during this period. By 168-169 A.D., additions including the Basilica, Capitol, Curia, Triumphal Arch, and the Gordian Palace further expanded the city, resulting in more elaborate water management systems [2]. Aqueducts in Volubilis drew water from two springs: Fertassa, located 1.4 km to the east, and Laksar, 3.5 km to the southeast (Figure 1).

The Romans heavily relied on topography and gravity in constructing aqueducts to transport water from high elevation springs and headwater streams to a network of water distribution canalization systems within their cities [3-8]. Literature shows that previous studies mainly utilized field observations [9,10] and geophysical techniques to demonstrate the existence of these Roman water systems. These aqueducts were essential infrastructure, providing water for drinking, sanitation, and irrigation. Water flowed through aqueducts via stone canals placed both above and below ground level, showcasing the engineering prowess of the Roman civilization in transporting water over long distances using gravity. While the aqueducts themselves may not be as well-preserved as other parts of the city, remnants and traces of these water channels are still visible within Volubilis.

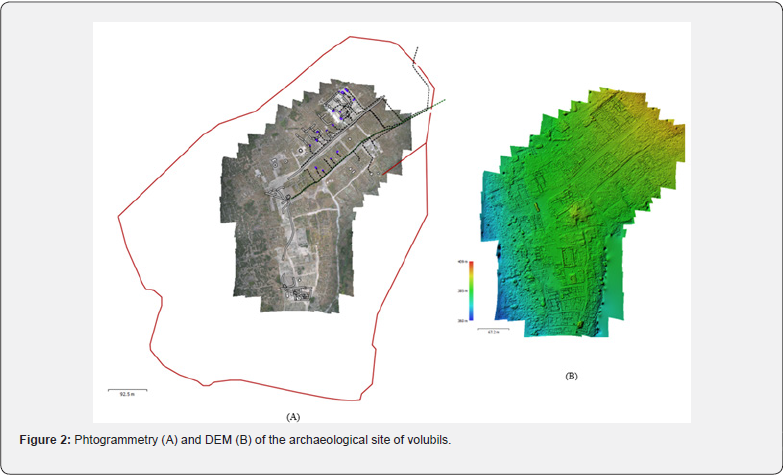

This study employs both photogrammetry and field observations to investigate these water systems. Photogrammetry techniques involve using Small Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs) to survey Volubilis and develop 3D models. UAVs (drone) was used to capture 155 photos from an elevation of 80 m. Figure 2 displays the orthomosaics map and a Digital Elevation Model (DEM) derived from the photogrammetric model, illustrating the orientation and direction of aqueducts in Volubilis. Analyses were conducted on these two models, and the results were confirmed through field observations.

Methodology

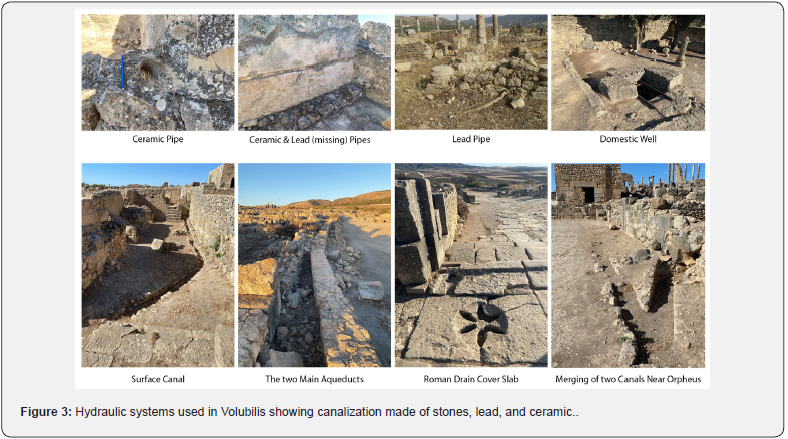

A Mavic 2 Pro with a 1-inch CMOS sensor was used to capture photos for the entire site (Figure 2), from which the House of Orpheus was extracted and magnified (Figure 3). The photogrammetric model was created utilizing a resolution of 5472x3648. Prior to use in Agisoft Photoscan, the photogrammetry software used in this study, all photos underwent post-processing in Adobe Photoshop Lightroom. The drone captured photos in both circular and zigzag patterns; circular mode was employed to enhance 3D model development and fill gaps in the survey taken by the serpentine flight pattern [12]. Flight planning and automatic image sampling were conducted in Map Pilot Pro (V5.4.0) using the Maps Made Easy processing service. Images were captured with 85% overlap along the flight direction and 80% overlap laterally between flight lanes. Field observations involved multiple visits to Volubilis to examine questionable locations, where photos and detailed records were obtained.

Results

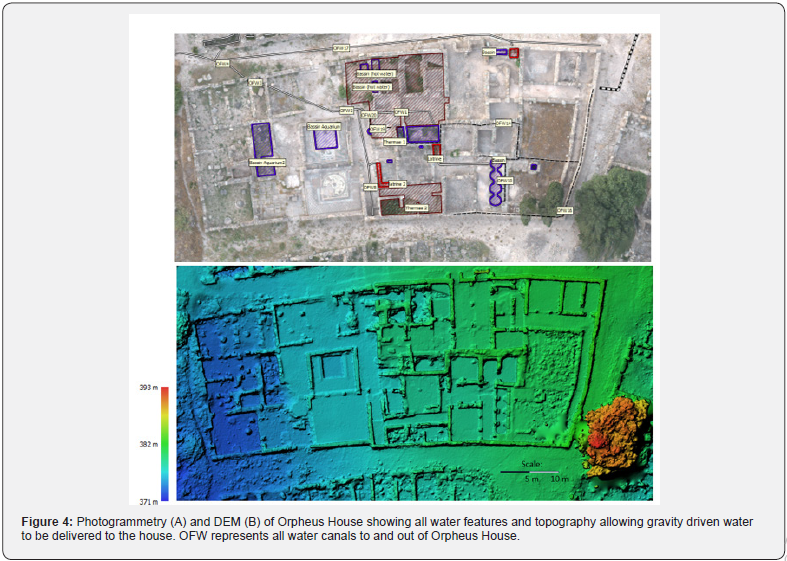

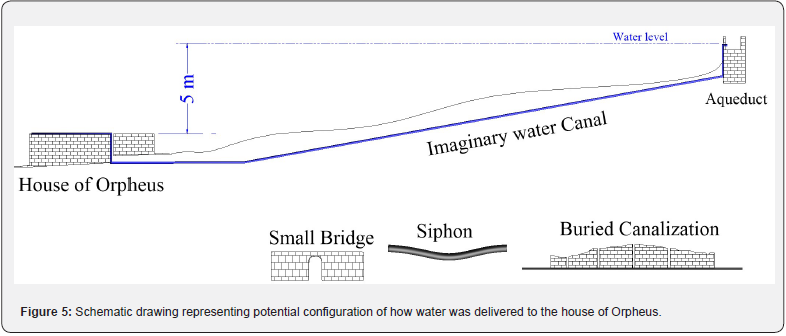

Photogrammetry revealed that water distribution within Volubilis to public and private buildings was facilitated through gravity-operated canalization and lead pipes (Figure 2, 3, 4, & 5). Three main categories of water distribution were identified: subsurface canals, intra-wall conduits made of ceramic or lead materials, or a combination of both (Figure 3). This information was gathered through on-site observations and detailed photogrammetric analyses. Although evidence is lacking regarding the continuity of certain water conduits, both methods provided sufficient information to reconstruct a conceptual model representing Volubilis’ hydraulic system. Various levels of complexity were observed in hydraulic systems across different locations. For example, the water distribution in the House of Venus featured a relatively straightforward and minimal canalization system, with a primary canal supplying water to a central basin (Impluvium) serving as the household’s water source. In contrast, the water system in the House of Orpheus was more intricate, with multiple water basins, latrines, baths, and two fountains (Figure 4). Both field observations and photogrammetric models indicated a water source for the House of Orpheus originating from the highest point on the wall (Figure 4 & 5). Water likely reached the House of Orpheus through a vertical pipe made from ceramic or lead raising water to this point, enabling distribution throughout the household. Gravity played a crucial role in bringing water to the house by pushing it upward to the top of the wall (Figure 5). The water level is about 5 meters elevation disparity between the aqueduct and the water point source on top of the house of Orpheus wall. Despite clear evidence of water systems, there is no visible indication of how water reached the upper section of the wall. One plausible hypothesis suggests involvement of siphoning, over-wall canalization, or a combination of both (Figure 5). Challenges encountered included missing canal pieces due to building collapses, particularly after the Meknes earthquake, which occurred three weeks after the Lisbon earthquake of 1755 [13]. Since photos were taken with GPS coordinates, photogrammetric analysis provided clear evidence which helped in connecting and tracking many water conduits from aqueducts to various locations within Volubilis (Figure 2). Photogrammetric models also enabled distance measurements in all directions to identify specific canal widths and lengths. Field observations were crucial in confirming and completing information derived from 3D photogrammetry models, especially in locations where water systems entered and distributed within houses. This was necessary because water conduit sizes tended to decrease as they approached their final discharge points, sometimes leading to inconclusive field observations due to missing or collapsed walls and buried underground.

This initial work has significantly enhanced the understanding of water distribution features in Volubilis, yet further exploration is warranted to complete the entire canalization system within the site. Another method that could provide additional information, especially regarding underground canal systems, is the use of geophysical techniques such as Ground Penetrating Radar (GPR) and/or Electric Resistivity Tomography (ERT).

References

- Limane H, & Rebuffat R (1992) The southern confines of the Roman presence in Tingitana in the region of Volubilis. In: Proceedings of the Fifth International Symposium on the History and Archaeology of North Africa, Avignon, 1990, pp. 459-480, Paris,1992.

- Étienne R (1954) Maisons et hydraulique dans le quartier Nord- Est à Volubilis dans Publications du Service des Antiquités du Maroc, fase. 10: 25-211.

- Hamey LA (1981) The Roman Engineers. Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Evans HB (1997) Water Distribution in Ancient Rome: The Evidence of Frontinus. University of Michigan Press, Reprint Edition.

- Evans HB (2002) Aqueduct Hunting in the Seventeenth Century: Raffaello Fabretti’s De Aquis et Aquaeductibus Veteris Romae. 1st Edition, University of Michigan Press, United States.

- Hodge AT (2002) Roman Aqueducts and Water Supply. 2nd Edition, Bristol Classical Press.

- Rinne KW (2011) The Water of Rome: Aqueducts, Fountains, and the Birth of the baroque City. 1st edition, Yale University Press, United States.

- Hodder I, Meskell L, Quinlan J, Watson A (2005) Excavations at Çatalhöyük: The 1995-1999 Seasons. Çatalhöyük Research Project Series Volume 4, McDonald Institute for Archaeological Research, Cambridge University Press, UK.

- Brewer D, Teeter E (2007) The Archaeology of Ancient Egypt: Beyond Pharaohs. Cambridge University Press.

- Akca İ, Balkaya Ç, Pülz A, Alanyal HS, Kaya MA (2019) Integrated geophysical investigations to reconstruct the archaeological features in the episcopal district of Side (Antalya, Southern Turkey). J Appl Geophys 163: 22-30.

- Moratti G, Piccardi L, Vannucci G, Belardinelli ME, Dahmani M, et al. (2003) The 1755 « Meknes earthquake (Morocco): filed data and geodynamic implications. Journal of Geodynamics 36(1-2): 305-322.

- Oleson JP (2009) The Oxford Handbook of Engineering and Technology in the Classical World. 1st edition, Oxford University Press, Australia.