From the Base to the Top: Walking through the Ritual Circuit of the Foldscape in Malpasito, Tabasco, Mexico

Hans Martz de la Vega*

Teacher, Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia

Zapote s/n, Isidro Fabela, Alcaldía Tlalpan, CP 14030, Ciudad de México, México

Submission: December 14, 2022; Published: February 01, 2023

*Corresponding author: Hans Martz de la Vega, Teacher, Escuela Nacional de Antropología e Historia Zapote s/n, Isidro Fabela, Alcaldía Tlalpan, CP 14030, Ciudad de México, México

How to cite this article: Hans Martz de la Vega*. From the Base to the Top: Walking through the Ritual Circuit of the Foldscape in Malpasito, Tabasco, Mexico. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2023; 12(5): 555850. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2023.12.555850

Abstract

Malpasito is a site that belonged to the macro area called Mesoamerica. It is believed that the Zoques occupied it during the Late Classic period, between 650 and 900 AD. However, this ethnic group moved from the XVII century to the lands that the Mayans occupy today. So that, it has been useful to make ethnographic analogies from the worldview, especially the one that deals with the relationship between the mountain and the essence of the soul of the heart of the Tzeltals. The general layout of Malpasito is based on a northeast-southwest guiding axis defined between the civic-ceremonial architecture, the top of the settlement and one of the hills to the south. This means that the site was dedicated to a worship related to the sacred mountain to which it is aligned. The arrangement of the site can be related to a ritual circuit from which the solstice and ideal dates such as the quarter days of the year are observed, both used to establish a 364-day computing year. The calendrical-astronomical/mantic families of significant day intervals for their calendrical and mantic are also present in the circuit and are part of the 364-day cycle. Through the currents of Christopher Tilley’s phenomenology of landscape, Felipe Criado Boado’s post-structuralism, Tim Ingold’s social theory and Pedro Pitarch Ramón’s ethnology, it was possible to propose that Malpasito has the configuration of a foldscape and, this, in turn, is part of a meshworkscape, generalized for Mesoamerica, in a relationship between a factor and its operator, between the general and the particular.

Keywords: Foldscape; Meshworkscape; Ritual Circuit; Sacred Mountain; Chalamal; Jamalal; Solstice; Quarter Day of the year; 364-days

Introduction

In general, the results that are exposed about Malpasito correspond to the first field season (2016-2018) of a research project dedicated to the analysis of the landscape, calendrical and cultural astronomy of pre-Hispanic sites, in which they have excavated and restored architecture, located in the territories of the Olmec, Zoque and Mayan cultures (PIAACPOM). Malpasito is the only pre-Hispanic site intervened in a vast territory, so an analysis from the perspective of this project is newfangled for the reader.

The general layout of the main Mesoamerican settlements has been the subject of discussion and debate for decades [1-3], with significant results that have given rise to new questions. Some of the layouts with a north-south orientation (with the respective rotation azimuth of each site), were associated with celestial phenomena, for example Teotihuacan and the Pleiades [4], or with landscape components [5] as hills [6] or even with settlements and ancestral places [7,8]. By studying the local aspects of each site, it will be possible to better understand the reasons for the building designs of those cultures.

The problem posed here is to unravel the motivation that the builders of Malpasito had to make a design oriented from the base to the top of the mountain hidden behind the Acropolis. The answer revolves around an ontological relationship in which humans and non-humans cohabited the same environment, in which mortals depended on the behavior of soul entities. The temporary agent was characterized, mainly, by the positions of the Sun on the mountains that are on the sides of the circuit and demarcated an annual cycle of 364 days. In addition, some of the dates that they observed on the horizon were dedicated to the maintenance provided by the agricultural ritual cycle.

Here, based on the general layout of the site and its horizon, the existence of a ritual circuit is exposed, as well as the development of the hypothesis that Malpasito is circumscribed in a landscape that allegories the metaphor of a meshwork and that it has been called foldscape. The route, through the site, was carried out based on the observation points (stations), mostly architectural structures that delimited the different sectors (complexes), and that can be understood as knots in a meshwork that unites human and non-human beings, and through which conductive threads were woven, which are the social relationships of life. Kathryn Reese-Taylor’s typology and Christopher Tilley’s phenomenology of landscape were used for the description. For the interpretation, the indigenous anthropology of Pedro Pitarch Ramón, and for the conceptualization, or perhaps theorization, the archeology of space by Felipe Criado Boado and the history of the life of the lines by Tim Ingold.

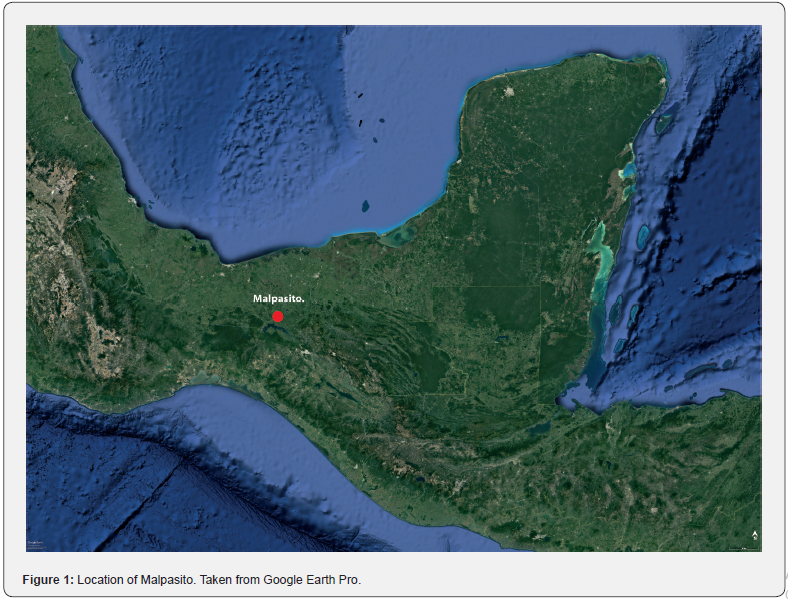

Location and Physical Environment

Malpasito is geopolitically circumscribed to the Municipality of Huimanguillo in the State of Tabasco, Mexico, some 2.7 km away from the border between the States of Tabasco, Chiapas and Veracruz (Figure 1). It is located within the XII Sierras de Chiapas and Guatemala Geological Province [9], specifically at the foot of the Cerro La Pava range of the Sierra de Huimanguillo, and about fifteen kilometers south of the limit between the mountains and the coastal plain (Gulf of Mexico). Altitudes in the Malpasito region can exceed 700 masl, such as Cerro Mono Pelado (c. 980 masl), which is among the highest peaks in the State of Tabasco. The altitude can vary drastically from one place to another [10]. The dominant agriculture is slash and burn, subsistence, since the soils are unsuitable and the land is difficult to work in addition to having excess water [11]. To reference the site, the access to the Acropolis (Structure 10) is used, whose geographical coordinates are 17.337444° N and 93.599389° W and an altitude of 274 masl.

In terms of hydrography, it is located in the Middle Grijalva basin, made up of the Grijalva river, which, near Malpasito and the homonymous town, is called the Mezcalapa river. This river is the source of the current Malpaso hydroelectric dam, southeast of Malpasito.

Background

The archaeologist in charge of excavating and restoring Malpasito, Francisco Cuevas Reyes [12], thought that the site probably belonged to the Zoque culture [13], and that it was built around 650 AD and vacated by 900 AD; that is, contemporary to the Epiclassic period of Central Mexico and to the Late Classic of the Mayans. In reality, there are several centuries between the occupation of the site and the Zoque presence documented by chroniclers [14,15].

The origins of the Zoque language have been the subject of debate since the first studies on the archaeological Olmecs. It is thought that their linguistic affiliation corresponded to the Mixezoqueans who at first could speak a Protomixe-zoque language until the year 1700 BC, when it was divided into Protomixe and Protozoque; the first belonging to the region of the archaeological site of San Lorenzo Tenochtitlan and the second to that of La Venta. Both languages began to fragment around 300 BC, assuming that it happened in the same historical process [16], and it was the Protozoque that was distributed towards the territory in which our study site is located. Norman D Thomas [17] elaborated the linguistic delimitation of the Zoques for the XVI century. To the west they reached what are now the States of Tabasco and Veracruz, so the Malpasito region was circumscribed in that cultural sphere.

One of the main aspects of Malpasito is its distribution with a north-south tendency (Figure 2), similar to the one that characterized the axial pattern of sites as old as La Venta in the Middle Preclassic [18]. In fact, at least since 600 BC, the materiality of the Olmecs will be, to a certain extent, the basis of the Protozoque society that manifested itself in the current States of Chiapas and Tabasco. In the Middle Grijalva basin, during the Protoclassic (1-250 AD), growth and consolidation of the large sites already considered Zoques can be seen. Later, its social composition collapsed, between 500 and 600 AD. However, the territory where the current Malpasito and Malpaso hydroelectric dams are located, around 500 AD, reached its greatest growth, and perhaps it was due to the influence of groups from the west of the Central Depression of Chiapas. In 900 AD, those sites were gradually abandoned, perhaps due to climatic circumstances, in addition to the fact that it could have been the cause of the arrival of groups from Chiapas, who probably caused, in turn, the migration of the Zoques in search of new lands [19].

The ballcourt is another of the aspects that have highlighted Malpasito, especially since it is a regional architectural variant. First, because it only has one end zone (cabezal); that is, the court is T-shaped, the same as the site of El Naranjo, 1.5 km to the northeast [12]. The other characteristic is that it is almost the largest in the region, as it is only surpassed by the double-court ballcourt at the López Mateos site, some seven kilometers to the southeast [12].

Theoretical-Methodological Framework

The field work in Malpasito consisted of measuring the orientations of each of the restored architectural structures and recording the horizon that is observed from each one of them, mainly of the elevated architectural complex (Complexes C and D). Also, the horizon of the top of the slope was measured (Complex E), and from where all the surrounding hills of the settlement can be seen. The measurement instrument was a YOM3 brand theodolite, model 4T30P-10, year 2002, with an arc error of 30’’ in both the horizontal and vertical angles. For data processing, the horizon astronomy software called Hansómetro [20] was used, and they were verified with the SkyChart/Cartes du Ciel 4.3 and Alcyone Ephemeris 4.3 software. The results were evaluated for the VII century because that is the time when the site is thought to have been built. To obtain the geographic coordinates, a Garmin brand GPS, etrex model, was used. The datum is WGS84. In the technical reports of the Malpasito excavations the term building appears, but here it was preferred to translate it into English as structure. As visual support, the photograph of the western horizon from the Crown Top is included because only from there it is possible to observe it completely and without obstructions due to the trees. It was not possible to capture the clear eastern horizon, so a photograph was not added. All dates presented have an uncertainty of ±1 day. Here each one of the points in space from where the observations of the local horizon were made is called a station. In general, the methodology used here is a continuation of the one that can be consulted in Martz de la Vega [21].

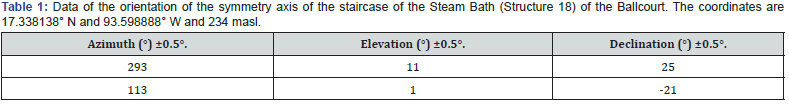

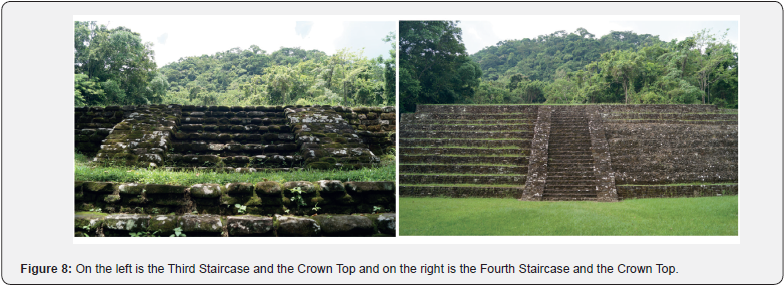

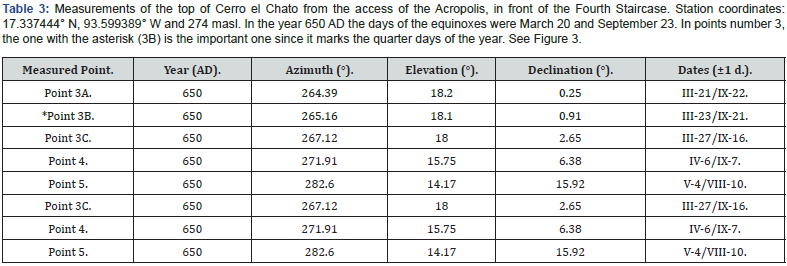

Table 1 has the data of the orientation of the symmetry axis of the staircase of the Steam Bath. Table 2 contains the orientations of the four staircases of Complex D. The ideal is to report the same element for each of the four staircases, for example, the starting step, but it was not possible to do it because it depends on the dimensions of the lengths of each element. But what stands out most about the staircases is that they seem to be oriented towards the Crown Top of the site, and it is the alfardas that clearly show this phenomenon. For the First Staircase, the starting step was considered because the alfardas are very small. For the Second Staircase, the alfardas could be considered. The Third Staircase is small in all its dimensions, but due to the fact that it is attached to a long rectangular structure with a similar orientation; that is, the last step is, in a certain way, part of that platform, so the wall of the structure was considered. For the Fourth Staircase the alfardas were used. Table 3 contains the horizon orientations mentioned in the work. All the horizon heights (elevations) reported in the tables are those that can be corroborated in the field; that is, they are presented without correction for atmospheric refraction so that they can be compared directly, but this does not mean that it has been ignored during the calculations.

Regarding the description and interpretation of the site, this work is based on some of the social theories applied to Archeology and Ethnology was also used. It begins with the proposal of a ritual circuit route through the site, following the categories of Kathryn Reese-Taylor [22], and considering the phenomenology of landscape of Christopher Tilley [23], because it is a changing landscape as we walk it, especially in terms of the positions of the Sun on the horizon, since the agency of the topography is incorporated into the construction of structures, making the ancestral power of the landscape remarkable. As the site is traveled, it is easy to identify some stations where the horizon and the Sun are related, or simply the architecture and the horizon. These are reminiscent of Tim Ingold’s metaphor of nodes forming a meshwork of lines. The interpretation is based on the fold concept developed by Pedro Pitarch Ramón [24,25] and its definition is:

“The fold is the mode of relationship between the two sides or states of the cosmos: the solar state inhabited by humans and the virtual state of spirits. The figure of the fold refers to the textile fabric, which represents a basic model of invention and transformation in Mesoamerican cultures, from the beginnings of textile art some 3000 years ago to the present” [25].

The use of the terms proposed for a meshworkscape and foldscape has been carried out based on the Xscape expressions of Felipe Criado Boado, but taking into account the skyscape of Fabio Silva and Nicholas Campion. For their part, Ivan Šprajc & Pedro Francisco Sánchez Nava [26] proposed an orientation for the Malpasito Acropolis, but due to the nature of this work it will not be mentioned later.

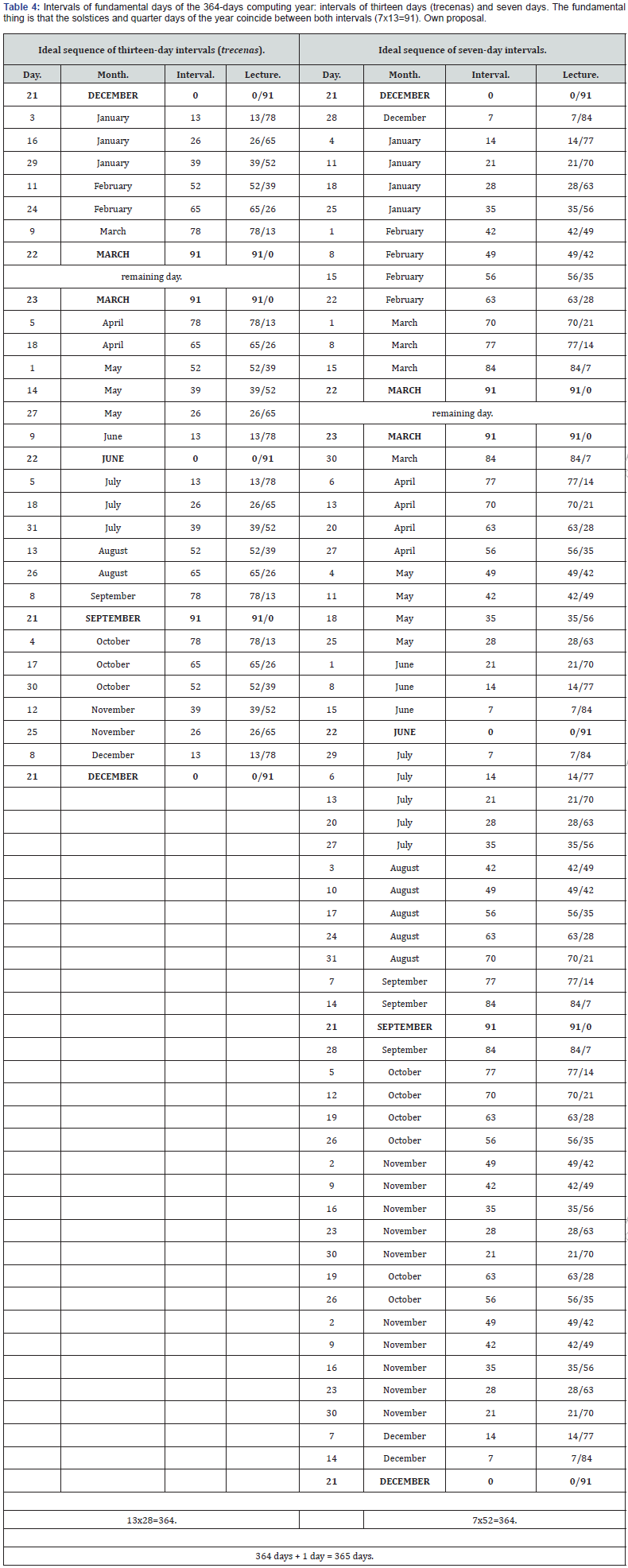

The calendrical and mantic issue is based on the work of pioneers such as Charles P Bowditch [27] and J Eric S Thompson [28], who studied the 364-day cycle. The interval counting method was based on the proposal of Vincent H Malmström [29], as well as on Arturo Ponce de León Huerta [30], who documented the quarter days of the year, and on Franz Tichy [31] for his model of thirteen days (trecenas), followed later by Jesús Galindo Trejo [32] and for the one who subscribes here together with colleagues Miguel Pérez Negrete & David Wood Cano [33].

The Ritual Circuit and the Main axes of the Layout

Layout, architecture and horizons

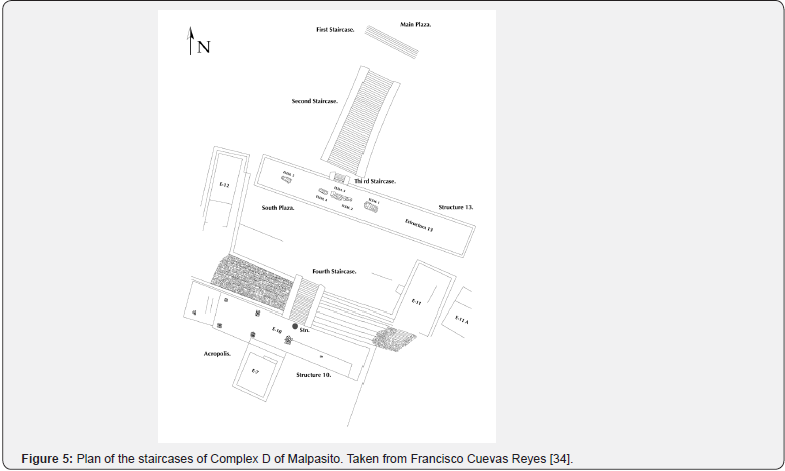

In the plan of Malpasito, presented by Francisco Cuevas Reyes [12], we can see most of the architectural structures recorded between 1990 and 2000 (Figure 2). For this work, complexes (A, B, C and D) were assigned to the sets of structures to develop the description of the site and its interpretation. Most of the excavation and restoration was carried out in Complex C and D, and both are characterized by being in the upper part of the settlement and by having monumental civic-ceremonial architecture, as well as consisting of three successive levels, communicated by different staircases and plazas. The first level is made up of the Main Plaza (at least Structures 15-25) and West Plaza (Structures 28-34) and is characterized as a ceremonial space by the presence of the Ballcourt and the Steam Bath. On the second level is the South Plaza (Structures 11-13) with a rectangular basement (Structure 13) with the main burials of the site. The third level is occupied by the Acropolis (Structures 6-10).

In the lower part of the settlement is Complex A (Structures 43- 54), of which a long platform (Structure 43) stands out, arranged with some structures aligned on one of its axes (Structures 50- 54) and another concentration on its east side (Structures 44-49). It is notable that between Structure 43 and its western horizon there are no constructions, highlighting that from there they made observations of the summer solstice, as we will see throughout this work. Complexes A and C-D are connected by a roadway, called Complex B (Structures 35-42). As the settlement is built on a natural slope and the top is part of the general layout, it was called Crown Top and is Complex E. Everything seems to indicate that there was no artificial habilitation on the top (personal communication from Francisco Cuevas Reyes), but it was a place of observation of the horizon. The general order tends to be northeast to southwest.

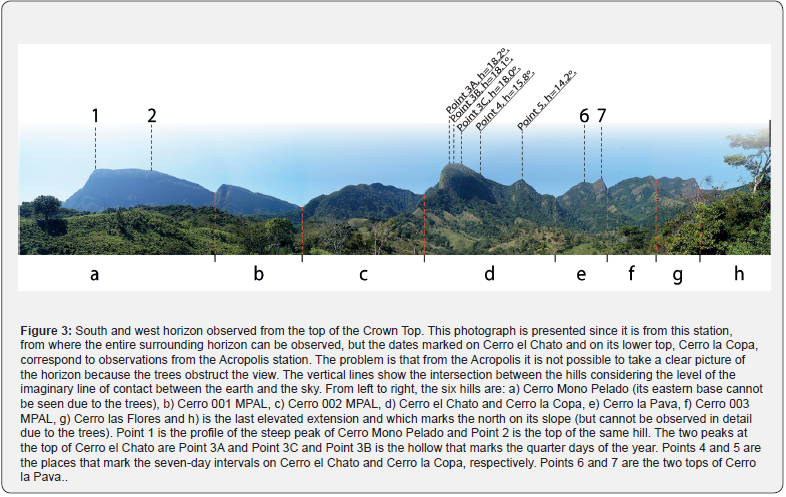

Two horizons stand out from the layout. The first is the one that can be seen from inside the architectural complexes (Complexes A-D) and the second is the one that corresponds to the Crown Top (Complex E), but only the southern region changes between them. From the two spaces you can see the hills of the western horizon: Cerro el Chato (c. 870 masl), Cerro la Copa (c. 840 masl), Cerro la Pava (c. 870 masl), Cerro 003 MPAL (c. 900 masl) and Cerro las Flores (c. 1020 masl), as well as to the east, highlighting only for this work the Chichonal or Chichón Volcano (with an altitude close to 1235 masl before the fracture of the dome in 1982, according to the Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas -UNICACH). All heights were obtained from the topographic plans of the Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (INEGI), unless another source is specified. As stated, the south is different. From the interior of Complexes A-D, the elevation of the land on which the layout was designed and the Crown Top can be observed, but from Complex E the view allows us to see Cerro Mono Pelado (c. 980 masl), Cerro 001 MPAL (c. 830 masl) and Cerro 002 MPAL (c. 840 masl). See Figure 3. In general, the western and southern horizon is close and high and is made up of the summits of the Cordillera la Pava that were already mentioned, while the eastern and northern horizon is low and distant, for example, the Chichonal Volcano is about 39.4 km away.

The ritual circuit, the observation stations and the guiding axis

In the layout of the site, several characteristic aspects of a ritual circuit of the type “from the base to the top” can be distinguished [22], whose setting is the landscape (horizon) as a function of time, recorded, mainly, with the sunsets. The circuit begins in the lowest part of the settlement where there are monumental structures, in Complex A. There is a large platform there (Structure 43), around which it seems that the remaining structures of the complex were distributed. What is striking is that, from one of the upper and central mounds of the platform (mound with coordinates 17.34086111° N, 93.59841667° W and 224 masl -it should be noted that the upper mounds of Structure 43 are not drawn on the Malpasito plan of Figure 2), the Sun is observed to set on the day of the summer solstice between the two summits of Cerro la Pava. The values of each summit are: A= 289.53°, h= 13.56°, δ= 22.33° and A= 292.37°, h= 14.48°, δ= 25.29°. In this way, there is the presence of solar positions on the horizon related to the origin of a count of days during the year in Mesoamerica from the solstice [31,34], an issue that will be clarified later.

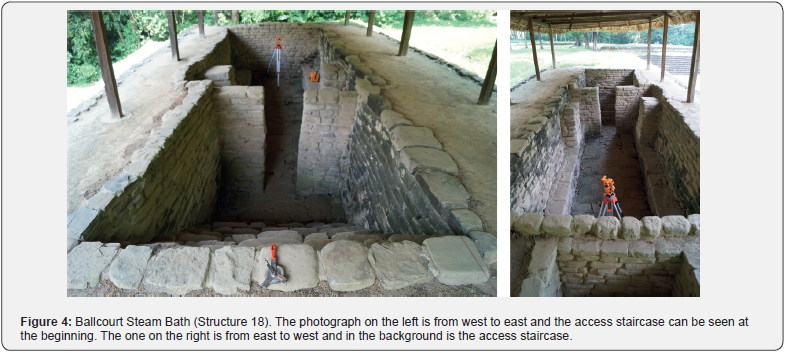

From there, the route continues uphill along a road delimited by some structures, which is defined here as Complex B, and which communicated with Complex C, with the civic-ceremonial monumental area. Access to Complex C was through a plaza (Plaza Oeste) distributed according to the Ballcourt, specifically its end zone (cabezal), but also the orientation of its court. From there, one enters the Main Plaza walking between Structures 20 and 29 and at first, one is in front of the Steam Bath of the apron (Structure 18) of the Ballcourt, which is almost oriented (symmetry axis of the access staircase), to the place where the Sun sets at the summer solstice, on the southern slope of Cerro la Pava (Figure 4, Table 1). As these are restored structures and the difference between the declination of the solstice and that of the structure is small, it can be thought that the intention of the orientation was solstitial.

The circuit continues to the south of the plaza where there is a series of staircases (Complex D), three of which can be seen oriented towards each other and their projection ends at the top of the slope on which they were built, the Crown Top (Complex E). It is notable that both the roadway and the staircases formed axes that start in the north and end in the south, specifically from northeast to southwest. The average axis of the last three staircases is 21.5° and differs approximately three degrees from the roadway of Complex B. The First Staircase has its own orientation, with a difference of about eight degrees with respect to the average of 21.5° of the other three staircases (Figure 5, Table 2).

The route continued up the staircases until reaching the top where the Fourth Staircase ends and the Acropolis begins. This axis shows how they oriented this last architectural section with respect to the top of the slope. This phenomenon in which structures with hills are centered had a relevant significance in places in Mesoamerica [35] and Malpasito is an emblematic case as we will see later (Figures 6-8).

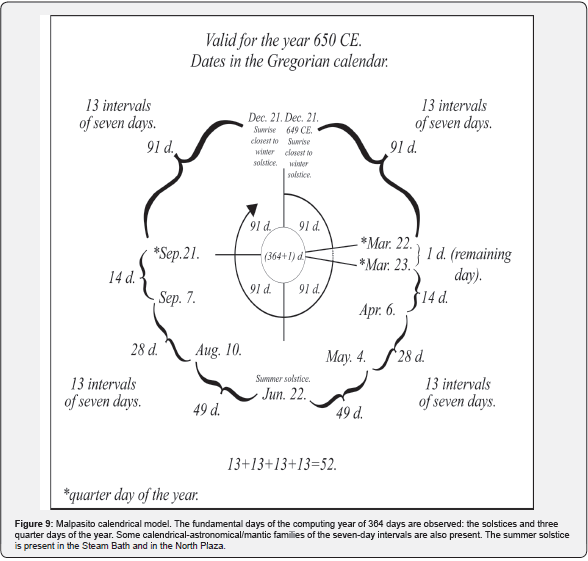

Once at the Acropolis, in front of its access staircase, the Sun was observed setting over the top of Cerro el Chato on the quarter days of the year, in March after the equinox and in September before the equinox, being that the specific days depended on each year. In general, from the civic-ceremonial center, Cerro el Chato, the southern slope of Cerro la Pava and little more than half of Cerro 002 MPAL occupied the entire space of the solar arc to the west. This means that Cerro el Chato was preferably solar for Malpasito, and also, its shapes and dimensions are distinguishable from the other two hills. Cerro el Chato contains a hollow between two small peaks at its main summit (Point 3B) in which the quarter days of the year were observed (Figure 3, Table 3). These days mean, in terms of the Mesoamerican calendrical, the presence of the 364-days computing year, since it was on those days that adjustments were made to obtain the main divisions of the cycle, divisions of 91 days, since 91x4=364. There were four divisions of 91 days each and to obtain them within the year of 365 days, they made adjustments of one day in March or September, depending on each year (364+1). In addition, the 364-day cycle is a multiple of thirteen and seven, two fundamental numbers of his worldview and calendrical, that is, 13x28=364 and 7x52=364. This means that the cycle was composed, essentially, of intervals of thirteen days (trecenas) and seven days, since 7x13=91; that is to say, that the intervals coincided in the solstices and quarter days of the year [37], as can be seen in Table 4. Thus, in this circuit they privileged the start and adjustment dates of the 364-day cycle, that is, it begins with the solstice and adjusts to 91 days with the quarter days of the year. Therefore, Malpasito is an emblematic case of this cycle.

The same higher elevation of Cerro el Chato has one more peak, but now on its northern slope, and it is the one that corresponds to Point 4 of Figure 3. There one of the calendrical-astronomical/ mantic families of seven-day intervals was observed. The dates are April 6 and September 7 and they make 77 days with respect to the summer solstice, the complete interval is read 77/14 since the sum must result in 91 days, fourteen being the days they have with respect to quarter days of the year. But also in its lower elevation, also known as Cerro la Copa (Point 5), it was observed from the Acropolis, the sunset on May 4 and August 10, being other families of seven days, in this case they are 49 days from the summer solstice and the full interval is 49/42 (Figure 3). In this way, the Cerro el Chato-la Copa was a marker of the 364-day cycle since it had the quarter days of the year and two of the families of seven-day intervals. The calendrical model is shown in Figure 9. In this specific case, May 4 corresponds to the modern festivity of May 3 of the modern agricultural ritual cycle, known as the Santa Cruz (Holy Cross), widely spread in Mexico, dedicated to the request for rain for good harvests, whose scenario is made up, mainly, of hills and milpas (maizefields) [38].

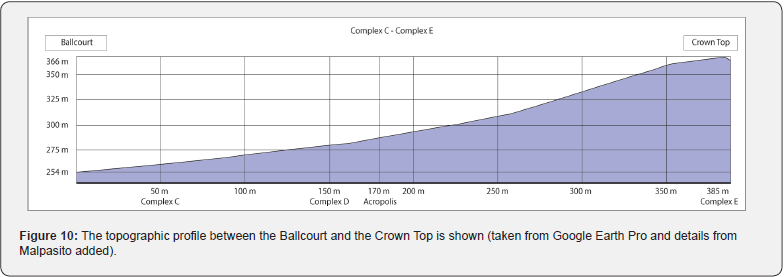

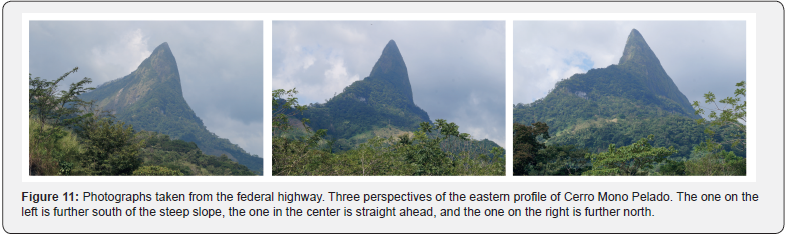

The circuit had one more station, but it was not in a set of architectural structures but on the top of the slope on which the civic-ceremonial center was built, the Crown Top (Complex E) (Figures 2, 3 & 10). From there, it is possible to observe all the hills on the horizon that are not seen in the other complexes, specifically those to the south: Cerro Mono Pelado and Cerro 001 MPAL. If we project the guiding axis of 21.5° to the south from the Main Plaza, we will see that it aligns with the top of the hill that is behind the Crown Top, Cerro Mono Pelado, so it seems that this was the intention of the builders of the site. Although Cerro Mono Pelado was not observable from the architectural complexes, they did consider it for its dimensions and shapes. In general, the hill has a pyramidal shape observed from the Crown Top, but it has other aspects that made it stand out, such as its eastern profile, which shows a steep and peaked slope, as can be seen in Figure 11, in addition to the fact that, there begins the series of hills that surround Malpasito (Figure 3), and at its base, below the steep peak, is the south.

Following the last idea, it should be said that Malpasito is surrounded by a series of hills, which are located at a distance of between 1.5 and four kilometers, which form a natural barrier. These begin in the north and end in the south, occupying the entire west (Figure 3). From the Acropolis, the last slope can be seen to end near the north (Figure 12, Point 8) and from the Crown Top the last base of Mono Pelado can be seen near the south. This means that the immediate hills, forming a mountain range, marked the north and south and between the two is the entire western arc.

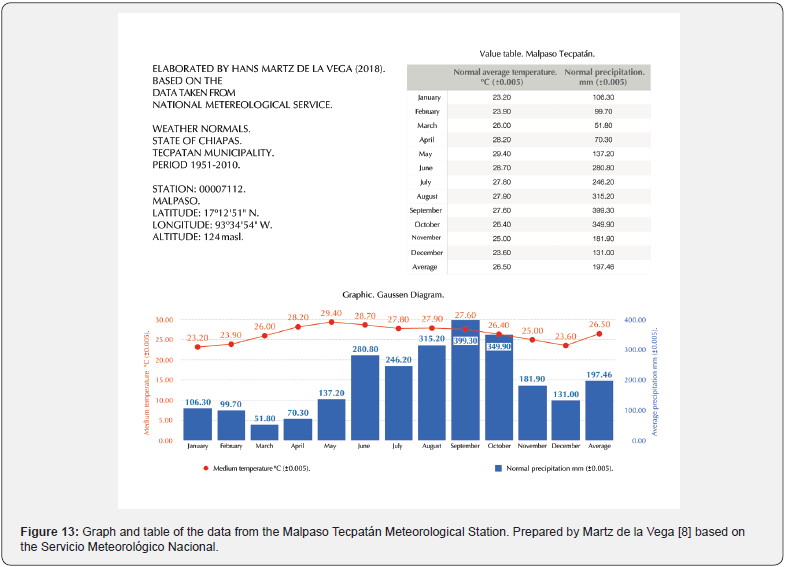

The four dates of the family of seven-day intervals of the Malpasito calendrical model are associated with the agricultural ritual cycle, so the ritual circuit included the worship of the request for rain to obtain maintenance, in other words, the good harvests of the year, especially maize. During the hot season, between April and early May the first rains begin and between August and early September is the beginning of the period of maximum rainfall (Figure 13). In fact, seven is the number that represents the abundance of food in the worldview and mantic of Mesoamerica. The calendrical names of the maize deities, during the Postclassic, in central Mexico, carried the seven, for example, Chicomecóatl (Seven Serpent) [39].

Another elevation that stands out in this work is the Chichonal Volcano, because, among other things, in the last centuries it was the Zoques who inhabited it. In addition to its dimensions and being in the solar arc of Malpasito and presenting significant dates, it is also important for its eruptive history (personal communication from Flora Salazar Ledesma). Before 1982, it was higher than it is today. In that year it made an eruption that destroyed the dome, which was 1235 masl or more. Thus, from the Acropolis, before a height of 1.25° could be observed, unlike today, which has 1° and an altitude between 1060 and 1080 masl. Maybe, this translates in terms of the calendrical, into a difference of one day for sunrises. The data related to the eruptive phenomenon and the shape of the dome can be found on the website of the Universidad de Ciencias y Artes de Chiapas (UNICACH). As for the dates when the Sun could be seen rising behind the volcano, it is possible that they are related to the significative intervals, towards the end of March and the middle of September. The relationship between the Sun and the horizon denotes the times in which some of the ritual activities were carried out.

In the spatial ordering of Mesoamerica, the east-west axes were derived from the movement of the Sun and are known as primary considerations [40]. The path of the Sun allowed them to demarcate directions and thus divide the world. Thus, the axis that can be seen between the civic-ceremonial center and the top of Cerro el Chato, and in which the quarter days of the year are implicit, was assigned the name of fundamental axis. On the other hand, when this binary division (east-west, light-dark or day-night), which fixed the horizontal division of space, became more complex, over the centuries during the Preclassic Period, due to sociocultural evolution, gave way to the assignment of properties to the two remaining directions, north-south, and thus a quadripartite division was formed [40]. From there arose axes that are less understood because the nature of their associations is unknown, especially based on the stars and the sky, so for each site there may be a particular interpretation like the one presented here for Malpasito. The guiding axis of the site is the axis with secondary considerations (north-south).

It should be said that the study of the guiding axis can be taken to regional studies if we consider the approximate angular value of 21.5° and its presence in other pre-Hispanic sites. For example, Ivan Šprajc & Pedro Francisco Sánchez Nava [26] emphasized a similar value, supported by the works of Bruce R Bachand [41], who proposed that on the Pacific Coast the architectural axis of 20° was intentional in the Middle Preclassic.

The Phenomenon of the Fold and the Lineages

As mentioned so far, the arrangement of the civic-ceremonial center with the Crown Top had the objective of maintaining a virtual orientation between the guiding axis and Cerro Mono Pelado. The study of this phenomenon led to La Cara Oculta del Pliegue (The hidden face of the fold) by Pitarch Ramón [24]. With this it is meant that the guiding axis has been the reason for making a proposal derived from ethnology about the Mayans, and to a lesser extent about the Zoques.

We know that the territory where Malpasito is located was inhabited during the XVI century by the Zoques. In the XVII century, after a series of geopolitical changes, the Zoques migrated to the neighboring regions of the State of Chiapas. In this way, they entered territories occupied by groups of Mayan affiliation, mainly by Tzeltals and Tzotzils. Thus, the oral tradition fragmented and was forgotten, but fortunately it happened partially. Their stories, which survived to this day, seem to be strongly syncretized with the ideas of the Spanish. However, everything seems to indicate that some of the conceptions about their worldview share foundations with those of the Mayans of the XX and XXI centuries.

So, after consulting data on orientation and mountains in the worldview of the neighboring towns of Malpasito, it was possible to propose some answers. Pitarch Ramón elaborated an ethnology on the Tzeltal thought of the people of Cancuc about the soul and the body. In some sections of his book, he shows the interest they have in the mountains. It says that the essence of the soul of the heart lies inside the sacred mountain, a place where it is guarded by the guide beings, spiritual entities, and it will depend on this that the body stays healthy, that it does not get sick, that it does not get lost, and so on. For all this to work in the best way, it is necessary to worship the mountains and the non-human beings that inhabit them, because if it is not done, it is said that they neglect the body, which is exposed to the dangers of life, because the souls are in constant activity and that is the cause of the evils, so it is necessary to reassure them.

In Cancuc there are four lineages and each one corresponds to a sacred mountain. These are distributed in a scheme tending to the cardinal type, in which the community was internalized in a pattern similar to a north, south, southeast and west distribution. Their sacred mountains are shaped like a pyramid. It should be said that Cerro Mactumatzá or Mactumactzá (c. 1160 masl), possibly its western mountain, has a name in the Zoque language. It stands out the fact that visits to these mountains are restricted and that somehow, they keep them under certain protection and discretion.

According to the Tzeltals of Cancuc, the essence of the heart lives in the Other Side or chalamal. In the fold, the human body is the figure in the foreground and the soul is the figure in the background. Body and soul make up the faces of a fold of which the hidden face is an interior domain with no determined spatial location. Something similar can be thought of for Malpasito and its southern mountain, Cerro Mono Pelado, which could be the hidden face of the fold, where souls lived and to which constant offerings had to be made; thus, a system oriented to these needs was built in Malpasito. This is, that the ritual circuit is destined towards the mountain.

Based on the above, ideas arise that can bring us closer to understanding the system to which Malpasito belonged. For the Tzeltals of Pitarch Ramón, the aspect of the sacred mountain is a place full of constructions, towns, rivers, mountains, etc., where the absence of the Sun engenders a time and a heterogeneous and qualitative geography (as immense as it is tiny from one moment to the next). This means, in the words of the ethnologist, that the mountains of souls are of a non-solar nature. In this work it is proposed that these mountains could be those from which the Sun does not rise or set from a station designed for the development of a ritual circuit and the related worship. In addition, Pitarch Ramón tells us that the sacred mountains, which although they are far from each other, maintain a close relationship in order to solve problems of great importance, especially for the preservation of lineages. For example, when one of the mountains is affected for some reason, then the souls of the lineage migrate to another of the sacred mountains and share the space with the local lineage. So, according to the above, the idea is that Cerro Mono Pelado was the sacred mountain of Malpasito, that of the people who belonged to a specific lineage.

Another notable aspect is that the names of the four sacred mountains of Cancuc tend to be dark, night, underground, descending; that is, to the hidden or to what is hidden: Ajk’abalnaj (Dark House or House of Night), Yalanch’en (Lower Cave or Cliff Cave), Ijk’alwitz’ (Black Mountain) and Mactumatzá (Hill of Water or Hill of the Eleven Stars).

Another of the properties of the mountains of the lineages, according to the Tzeltals of Cancuc, is to carry out the trials and execute the sanctions of the people in their charge, but when it comes to something complicated, of the maximum severity or a delayed verdict, the mountains solve them together; that is to say, when the mountain faces its own limits, when it cannot do it alone, it meets with the others to dictate and exercise the verdict. Regarding this matter, it seems that, in Malpasito, the hills on the western horizon, due to their proximity to each other and also to the settlement, meant an important component of the system in a broader sense. Thus, we could be in front of a place where the mountains of the lineages were symbolically represented, a place where larger or more delicate issues were resolved. In short, the spaces and their route are integrated with the places in the landscape where the humans communicated with non-human entities.

This last idea only tries to look for relationships between lineages. However, when consulting the ethnographies of the Zoques, we find that all the paths that unite the Zoque peoples and connect to the sacred mountains converge in the hills: the Cerro del Chile, which is the home of sorcerers, the Tecpatán, where the maize and cocoa were extracted or the Cerro de Chicoasén where the spirits of the nahuales inhabit [42-44].

A Foldscape in a Meshworkscape

After inquiring into the social complexity of Malpasito through the relational fields, which in this work were considered places of worship and observation, it is necessary to deal more thoroughly with the landscape and its events. Thus, in the next step of this analysis, it is possible to characterize Malpasito and its landscape with a unitary concept based on proposals such as that of Felipe Criado Boado [45], that of Xscape, where a landscape can be described as something social. In Criado Boado there is an Xscape factor and multiple X-scape operators. Xscape underlies and circumscribes X-scape, the latter being the one that can have an endless list of terms.

It seems that the materiality of Malpasito’s spatial organization resembles Tim Ingold’s meshwork [46], which is made up of knots or places and lines along which life is lived, and therefore, each of them are a relationship. The point is that it is not a question of delimiting a settlement, but of studying the life of the lines of a certain site in which different paths are completely entangled, in this case, alignments. That being said, a meshworkscape is posed here as an Xscape. This is a conception of space typical of a sociocultural formation in which the relational fields function as meshes of social relations. In terms of this interpretation for Malpasito, landscape-of-mesh (meshworkscape) underlies a way of socializing space in geopolitics.

In an analogous way, Malpasito could be considered as a foldscape, where the guiding axis indicates the place where the fold is located, exactly at the Crown Top, from where both faces can be seen, the one in the civic-ceremonial center, constituting the jamalal (term of Zoque origin), which means this world, result of the appearance of the Sun, solar state. The foldscape is a particularity of Malpasito, an X-scape operator. The foldscape belongs to the meshwork because it is also a meshwork; it contains a line that delimits two faces of the same existence, through which life passes, simultaneously cohabiting on different planes. The fold separates and simultaneously puts the virtual in contact with the actual.

Conclusion

Everything seems to indicate that in Malpasito there is a combination of significant intervals, generating a calendrical model. Regarding the landscape as a social construction that arises from the constant contact and relationship between the beings that inhabit the space and their environment, it was possible to propose a general landscape (meshworkscape), but also to define a particular landscape (foldscape). It would be important to find more sites with these characteristics to be able to make comparisons in order to know if there was a common pattern.

Acknowledgment and Dedication

First, I want to thank the Archaeologist Francisco Apolinar Cuevas Reyes for his willingness to face possible new studies on Malpasito and I want to extend it to the authorities of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia, among whom archaeologist José Luis Romero Rivera and Drs. Pedro Francisco Sánchez Nava† and Ivan Šprajc. Of course, to the custodians of the site, Berzain Hernández Cortez, Pedro Aguilar † and Benjamín López Luna, for their attentions, information and company on the walks. In the academic part, Dr. Stanisław Iwaniszewski who allowed a part of the first field season to be my master’s thesis (2018). Without his advice, this work would not have reached the final proposal and in the sameway to my master’s advisors, Drs. Erik Velásquez García and María Elena Vega Villalobos, and I extend my thanks to Dr. Daniel Grecco Pacheco. To Dr. César González García for considering that this document could go through an opinion process. To Dr. Pedro Pitarch Ramón for reading it, and giving me his opinion. To Master Cecilia González Morales for the treatment of the drawings and her support in the field. To David Wood Cano who shares the idea that the aforementioned day intervals were significant in Mesoamerica. I dedicate this work to Stanisław Iwaniszewski.

References

- Ashmore Wendy, Jeremy A Sabloff (2002) Spatial Order in Maya Civic Plans. Latin American Antiquity 13(2): 201-215.

- Ashmore Wendy (1991) Site-Planning Principles and Concepts of Directionality among the Ancient Maya. Latin American Antiquity 2(3): 199-226.

- Smith Michael E (2008) City planning: Aztec city planning. In: Helaine Selin (ed.), Encyclopaedia of the history of science, technology, and medicine in non-western cultures. Volume 1 A-K, Springer, pp. 557-587.

- Aveni Anthony F (2000) Out of Teotihuacan. Origins of the celestial canon in Mesoamerica. In: Davíd Carrasco, Lindsay Jones & Scott Sessions (eds.), Mesoamerica’s classic heritage: from Teotihuacan to the Aztecs, University Press of Colorado, United States, pp. 253-268.

- Ashmore Wendy (2009) Mesoamerican Landscape Archaeologies. Ancient Mesoamerica 20(2): 183-187.

- Tate Carolyn E (1999) Patrons of shamanic power: La Venta's supernatural entities in light of Mixe beliefs. Ancient Mesoamerica 10(2): 169-188.

- Iwaniszewski Stanisław (2016) The temple of the inscriptions in the spiritual landscape at Palenque. In: Fabio Silva, Kim Malville, Tore Lomsdalen & Frank Ventura (eds.), The Materiality of the Sky. Proceedings of the 22nd Annual SEAC Conference, 2014. Sophia Centre Press: Lampeter, United Kingdom, pp. 267-287.

- Martz de la Vega Hans (2018) The Architectural Orientation and its Relationship with the Landscape in Archaeological Zones of Maya, Olmec and ProtoMixe-Zoque Origin. Cases of the State of Tabasco, Mexico. Master's Thesis, National School of Anthropology and History: Mexico.

- National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) (2001) Síntesis Geográfica del Estado de Tabasco. Mexico.

- National Institute of Statistics and Geography (INEGI) (2011) Topographic Chart E15C38d Chiapas, Tabasco and Veracruz. Scale Mexico, 1: 20000.

- Romero David (2011) Delimitation, Physical Characteristics and Landscape. In: Ana García de Fuentes & David Romero (coords.), Atlas Geoturístico de la Sierra de Tabasco. National Autonomous University of Mexico, Council of Science and Technology of the State of Tabasco: Mexico, pp. 11-32.

- Cuevas Reyes Francisco A (2004) El Juego de Pelota de Malpasito, Huimanguillo, Tabasco. Archaeology 33: 47-59.

- Terreros Espinosa Eladio (2006) Zoque Archaeology of the Serrana Tabasqueña Region. Mesoamerican Studies 7: 29-43.

- Lowe Gareth W (1983) The Olmecs, Mayas and Mixe-Zoques. In: Lorenzo Ochoa & Thomas A Lee Whiting (eds.), Antropología e Historia de los Mixe-Zoques y Mayas: Homenaje a Frans Blom. Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México: Mexico, Brigham Young University: UTAH, United Sates, pp. 125-130.

- Schumann Otto (1985) Historical Considerations About the Indigenous Languages of Tabasco. In: Lorenzo Ochoa (coord.), Olmecas y Mayas en Tabasco: Cinco Acercamientos. Gobierno del Estado de Tabasco, Instituto de Cultura de Tabasco: Villahermosa, Tabasco, pp.113-127.

- Davletshin Albert & Erik Velásquez García (2018) The Languages of the Olmecs and their Writing System. In: María Teresa Uriarte (ed.), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Jaca Book: Mexico, pp. 219-243.

- Thomas Norman D (1974) The linguistic, geographic, and demographic position of the Zoque of southern Mexico. Papers of the New World Archaeological Foundation, 36, Brigham Young University: Provo, UTAH, United States.

- Clark John E & Richard D Hansen (2001) The architecture of early kingship: comparative perspectives on the origins of the Maya royal court. In: Takeshi Inomata & Stephen D Houston, Royal Courts of the Ancient Maya, Volume Two: Data and Case Studies. Westview Press: Boulder, Colorado, pp. 1-45.

- Linares Villanueva Eliseo (2016) The Zoque region in pre-Hispanic times. In: Zoque Ecoregion: Challenges and Opportunities in the face of Climate Change. Secretaría de Medio Ambiente e Historia Natural: Mexico, pp. 111-128.

- Martz de la Vega Hans, Moyano Vasconcellos Ricardo, Iwaniszewski Stanisław & Miguel Pérez Negrete (2021) Hansometer: Free Program for Computing Archaeoastronomy in Excel. In: Stanisław Iwaniszewski; Ricardo Moyano Vasconcellos & Michał Gilewski (eds.), La Vida Bajo el Cielo Estrellado: la Arqueoastronomía y Etnoastronomía en Latinoamérica, Warsaw, Poland, pp. 335-346.

- Martz de la Vega Hans (2018) Case studies with archaeoastronomic approach in the State of Tabasco, Mexico. Mediterranean Archaeology and Archaeometry 18(4): 233-240.

- Reese-Taylor Kathryn (2002) Ritual circuits as key elements in maya civic center design. In: Andrea Stone (ed.), Heart of creation. The Mesoamerican world and the legacy of Linda Schele. The University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa and London, pp. 143-165.

- Tilley Christopher (1994) A phenomenology of landscape. Places, paths and monuments. BERG, Oxford: United Kingdom, Providence, United States.

- Pitarch Ramón Pedro (2013) The Hidden Face of the Fold. Indigenous anthropology. Artes de México, Consejo Nacional para la Cultura y las Artes: Mexico.

- Pitarch Ramón Pedro (2018) The Fold Line. Essay on Mesoamerican Cosmology. Mana 24(1): 131-160.

- Šprajc Ivan & Pedro Francisco Sánchez Nava (2015) Astronomical Orientations in the Architecture of Mesoamerica: Oaxaca and the Gulf of Mexico. Prostor, kraj: Ljubljana, Slovenia.

- Bowditch Charles P (1910) The numeration, calendar system, and astronomical knowledge of the Mayas. Harvard University Press: Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA.

- Thompson J Eric S (1950) Maya hieroglyphic writing. Introduction. Publication 589, Carnegie Institution of Washington: Washington D.C., United States.

- Malmström Vincent H (1978) A reconstruction of the chronology of Mesoamerican calendrical systems. Journal for the History of Astronomy, ix: 105-116.

- Ponce de León Huerta, Arturo (1982) Fechamíento Arqueoastronómico en el Altiplano de Mé General Directorate of Planning, Department of the Federal District, Mexico.

- Tichy Franz (1990) Orientation calendar in Mesoamerica: hypothesis concerning their structure, use and distribution. Estudios de Cultura Náhuatl 20: 183-199.

- Galindo Trejo Jesús (2004) Ordenación Calendárico de la Arquitectura Mesoamericana. Pre-Hispanic mural painting in Mexico. Newsletter X(20): 16-20.

- Martz de la Vega Hans, Wood Cano, David & Miguel Pérez Negrete (2016) The Family of the 78-Day Interval, Calendrical-astronomical Family of 260/105 Days in its Relationship with Ethnography and Sources. In: Priscila Faulhaber & Luiz C. Borges (orgs.), Perspectivas Etnográficas e Históricas sobre as Astronomías, Museu de Astronomia e Ciências Afins: Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, pp. 77-94.

- Cuevas Reyes Francisco A (1994) Informe Parcial. Malpasito Archaeological Project, Tabasco. 1993 season. Technical Archive of the Council of Archaeology, National Institute of Anthropology and History, Mexico.

- Martz de la Vega Hans & Miguel Pérez Negrete (n.d.) A calendrical model of seven-day intervals in the architecture and landscape of Tehuacalco, Mexico. European Society for Astronomy in Culture (SEAC): Bulgaria, in press.

- Cuevas Reyes, Francisco A (1997) Miniguía Malpasito Tabasco. Mediateca, Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia: Mexico.

- Martz de la Vega Hans (2020) Archaeoastronomy of the Temple of New Fire Architectural Complex. In: Ismael Arturo Montero García (coord.), El Santuario del Fuego: Cerro de la Estrella in Iztapalapa. Alcaldía Iztapalapa: Mexico, pp. 110-129.

- Villela Flores Samuel (2009) Indigenous Cosmovision 13. In: Estado del Desarrollo Económico y Social de los Pueblos Indígenas de Guerrero, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, PUMC, Secretaría de Asuntos Indígenas del Gobierno del Estado de Guerrero: Mexico, pp. 465-507.

- Dehouve Danièle (2014) The Imaginary of Numbers among the Ancient Mexicans. Center for Mexican and Central American Studies (CEMCA): Mexico.

- Iwaniszewski Stanisław (1995) Symbolic Spatial Ordering among the Maya: Primary Associations. The Word and Man 95: 83-92.

- Bachand Bruce R (2013) The Formative Phases of Chiapa de Corzo: New Evidence and Interpretations. Estudios de Cultura Maya XLII: 11-52.

- Baez-Jorge Felix, Rivera Balderas, Armando & Pedro Arrieta Fernández (1985) When Heaven Burned and the Earth Burned. Socioeconomic and Sanitary Conditions of the Zoque Peoples Affected by the Eruption of the Chichonal Volcano. Instituto Nacional Indigenista, Mexico.

- Reyes Gómez Laureano (1988) Introduction to Zoque Medicine. An ethnolinguistic approach. In: Susana Villasana Benítez & Laureano Reyes Gómez (eds.), Estudios Recientes en el Área Zoque. Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas: Tuxtla Gutierrez, Mexico, pp. 156-383.

- Velasco Toro José (1991) Territorialidad e Identidad Histórica en los Zoques de Chiapas. The Word and Man 80: 231-258.

- Criado Boado Felipe (2015) Archaeologies of space: an inquiry into modes of existence of Xscapes. In: Kristian Kristiansen, Ladislav Šmejda & Jan Turek (eds.), Paradigm found. Archaeological theory – Present, past and future. Essays in honour of Evžen Neustupný. Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 61-83.

- Ingold Tim (2007) Lines: a brief history. Routledge, London.