Fire in the Genesis of Laguna Merin Basin Mounds. The Visualization through the thermoluminescence Dating Techniques

Roberto Bracco Boksar`1*, Christopher Duart`e2, Ofelia Gutiérrez3, Andreina Bazzino3, Natalia Alonso2 and Y Daniel Panario3

1Department of Humanities and Education Sciences, Universidad de la República, Uruguay

2 Department of Sciences, University of the Republic, Uruguay

3Department of Sciences, University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay

Submission: July 09, 2019; Published:November 14, 2019

*Corresponding author:Department of Humanities and Education Sciences, Universidad de la República, Montevideo, Uruguay

How to cite this article:Roberto Bracco Boksar, Christopher Duarte, Ofelia Gutiérrez, Andreina Bazzino, Natalia Alonso, Y Daniel Panario. Fire in the Genesis of Laguna Merin Basin Mounds.The Visualization through the thermoluminescence Dating Techniques. Glob J Arch & Anthropol . 2019; 11(1): 555804. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2019.11.555805

Abstract

The study of the genesis of the mounds of the Laguna Merín basin focused on the contribution of sediments and discarded elements. Investigations based on the geochemistry of the matrix led to consider the role of fire in its elevation. We try to contrast their presence using the techniques of luminescence dating. If different fractions of the matrix present ages or paleodosis OSL/TL statistically not differentiable, then the bleaching agent would be heat. The hypothesis was confirmed in mounds of three archaeological sites located in the southern area of the basin. We can verify that we are faced with recursive practices, which produce accumulations of thermo-altered sediments. This led us to earth ovens and Australia’s oven mounds. Prehistoric oven earths have been identified in Uruguay. The oven mounds are a powerful ethnographic-archaeological analogue that illustrates the formation processes of thermo-altered sediment accumulations, while allowing addressing socio-economic and symbolic aspects. Finally, from the implications of the hypothesis, we pointed out the pertinence of approaching the mounds in two scales. One would correspond to the behaviors that elevated them and the other to their reality as patches within the landscape.

Keywords: Mounds genesis; OSL / TLD; Fire; Earth ovens

Abbreviations: LMB: Laguna Merin Basin; TLD: Thermoluminescence Dating; OSLD: Optical Stimulation; MAAD: Multiple Aliquot Aditive Dose; MARD: Multiple Aliquot Regenerative Dose; TQ: Burned Earth; De: Equivalent doce; Gy: Gray

Introduction

The investigation of the genesis of Laguna Merin Basin (LMB) earth mounds, has paid special attention to the contribution of sediments and discarded elements. This becomes evident when they are characterized as earth works that integrate waste of human activities as well as human burials [1-5]. Researches focusing on the geochemistry of the matrix have led us to consider the role of fire in the construction processes [6]. In this article we present a series of luminescent data that verify the hypothesis that fire was present in the construction processes. At the same time, we interpret this new evidence in the light of earth ovens technology, which leads us to an ethnographic-archaeological analogue: the oven mounds of Australia.

Materials and Methods

Luminescence dating techniques are based on the property of some minerals, such as quartz and feldspar, of accumulating ionizing energy and releasing it when stimulated with light or heat (bleaching). This energy (background radiation) comes in nature, from unstable natural isotopes and from the universe (cosmic rays). The amount of accumulated energy (paleodose) is proportional to the intensity of background radiation and to the time elapsed since the mineral was last bleached; therefore, if paleodose and radiation intensity are estimated, the time elapsed since bleaching can be calculated [7,8]. The bleaching is total when the mineral is exposed to enough temperature “restarting the thermoluminescent and luminescent clock”, and partial when exposed to light “re-starting the luminescent clock”. In the latter case there remains an energy remnant that is only released if the mineral is heated. If the event to be dated is contemporary with a heat bleaching, both the technique of thermoluminescence dating (TLD) or the technique of dating by optical stimulation (OSLD) can be used. In the case that the event to be dated is coeval with a bleaching by light, only the OSLD dating technique is used, using TLD would estimate a higher paleodose (older age) since it will integrate the energy remnant that was not released with the sample’s exposure to light only. This indirectly allows us to know the bleaching agent. When OSLD and TLD paleodoses are statistically indistinguishable they are indicating heat bleaching.

Hypothesis and background

Our work hypothesis is: if the OSLD and TLD paleodoses of the same fractions of the matrix coming from the same level, are statistically not differentiable, then the matrix was exposed to heat, at enough temperature so that the entire luminescent record had been bleached. This hypothesis has already been contrasted in the García Ricci and Los Ajos sites (Bracco et al. 2019) (Figure 1).

Data presented here comes from mounds 1, 2 and 3 of the Pelotas sites (33o27’26.26 “S-53o50’28.05” W). This archaeological site is composed of 9 mounds of 1.5 to 3.5 meters in height. It is located on the right bank of the homonymous stream, on a plain that develops at an elevation of 11 meters above sea level in the department of Rocha, Uruguay. With the assistance of a soil sampler (AMS™), successive vertical samples of the matrix were taken in the center of the mounds, jacketed in PVC tubes of 15cm in length, from peak to base. Samples were processed in the Laboratory of Luminescence of Faculty of Sciences, University of the Republic. Under appropriate artificial red light (645-700nm) the fine sand and silt fractions were separated and treated to measure their luminescent signals with a Daybreak 1100 automatic reader. To estimate the equivalent dose [7,9] a Daybreak ™ Model 801E irradiator equipped with a 90Sr beta source was used (0.0597 Gy/s September 2000).

The TLD measurements were performed under a nitrogen atmosphere, following the MAAD method [10]. The region of the spectrum used to determine the equivalent dose was selected by the plateau method [7]. The OSLD measurements were made following the MAAD and MARD method [10]. Series of 6 aliquots were measured to estimate the intensity of natural signal and of the 4 irradiation steps. To reduce dispersion caused by differences in sensitivity or load, the OSLD measurements of the sand fraction included a previous measurement of 0.15 seconds of all aliquots. From these data, a correction factor was calculated. In all cases, only the series of measurements that had a CV ≤ 5% were accepted as valid, ruling out a maximum of two measurements, otherwise, the series was repeated.

Results

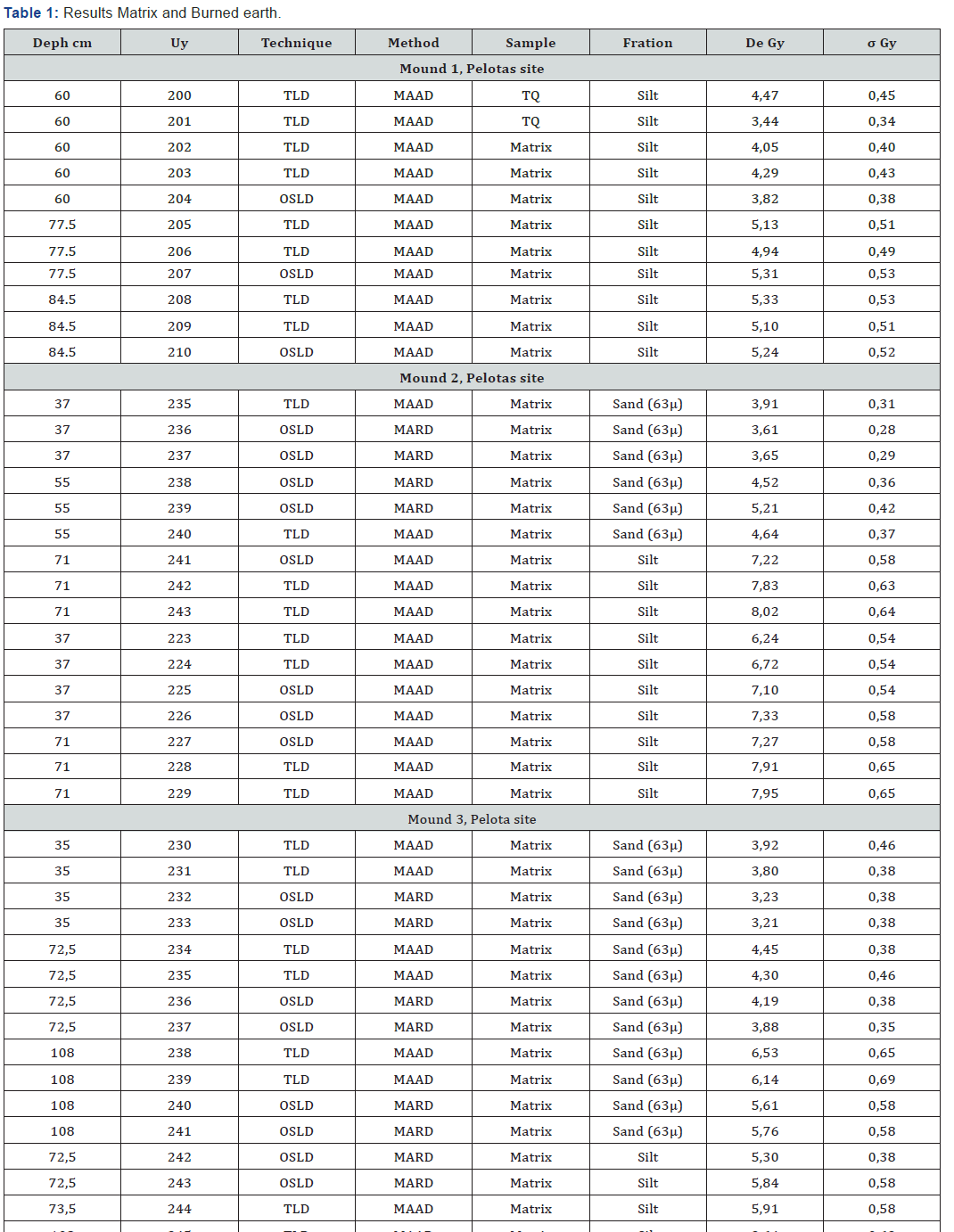

The χ ^ 2 values allow us to observe that paleodoses determined by duplicate for the same fractions of the matrix coming from the same level, are statistically not differentiable for TLD or OSLD (Table 1). Accordingly, weighted average TLD and weighted average OSLD from samples of the same fractions and the same provenance, are also not statistically differentiable. Paleodoses determined from the silt fraction are higher than those determined from the sand fraction because in the sand fraction the record of the alpha particles was eliminated [7].

Discussion

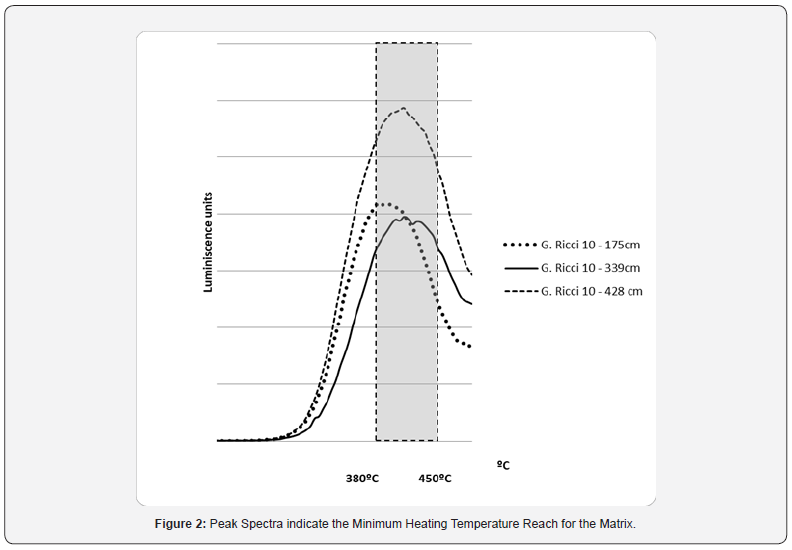

Paleodoses estimated by OSLD and TLD techniques for the different fractions of the mound’s matrix and for the same levels are statistically not differentiable, so we conclude that the bleaching agent was heat. The peaks of the spectra indicate that the minimum heating temperature reached for the matrix was in the order of 380oC (Figure 2). Many human practices produce thermo-alteration of sediments, however, those that recur in the same place, during very long periods of time, originating mounds, are not so common. The oven mounds, Australian earth mounds, are concordant with both aspects, thermo-altered and accumulated sediments. Earth mounds are a characteristic archaeological feature of the lower basins of the West, South Alligator and Murray rivers of southern and northern Australia, their research has been based on ethnographic and archaeological information [11,12]. They have circular or oval plants, reaching 200 meters long, and 2 meters height. They are found in floodplains or in their limits. They are recognized as multifunctional sites that were occupied seasonally [11]. The spatial distribution of the mounds suggests an economy focused on aquatic ecosystems. This is supported by ethnohistorical references [12]. In the north, the earliest chronologies of earth mounds reach 4600 years 14C AP [11]. In the south they reach 4330 years 14C AP. Their elevation was progressive, some took short periods of 300 years and others longer periods, above 2000 years [12] (Figure 2). The presence of heat accumulator fragments made of clay, noted by Jones et al. [12], indicates that the main mechanism of mound growth is the sequential use of earth oven technology during long periods, supplemented with occupational waste. Brockwell [11] reports, for the northern region, different researchers who, based on the same evidence, propose the same principal mechanism of elevation. Accumulation of waste produced using earth ovens (mainly heat accumulators) in the same place over long periods, is indicated as the main cause of mounds’ growth. [12] emphasize that beyond the choice of location for economic factors and the main mechanism of growth, the mounds may have been imbued with a cultural, social and / or spiritual meaning. In the region of the Reynolds and Alligator rivers they have been used as burial sites [11].

Black & Thoms [13] (Figure 1) describe a ground furnace as a cooking device arranged in layers within a pit. It starts with the fire, arranging the heat accumulators inside and around it. Once the fire diminishes, the accumulators are placed below and above the food packaged with vegetables. Layers of vegetables are often arranged between accumulators and food. Finally, the oven is sealed with sediment, bark or leather. Heat accumulators reported for North America and Europe are rock fragments [13-15]. In Australia, clay balls are used [16]. Ethnographic information indicates that fragments of termite nest were used as heat accumulators for the Reynolds River and the Blyth River regions. According to Black & Thoms [13] most of the ovens earth layers are rarely discernible in the archaeological record, but not the heat accumulators.

Black & Thoms [13] point out that earth ovens are specialized plant processing facilities, dating back to the beginning of the Holocene in America. Thoms [15] indicates that its use intensified among hunter-gatherers in western North America between 4,000- and 2,000-years BP, when abundant and accessible plant resources, which require prolonged cooking to increase their nutritional value, were integrated into the diet [14] Wandschnider 1997. According to Black & Thoms [13] sites of earth ovens are often reused hundreds of times over centuries or millennia. Some of the elements incorporated during their use are removed or perishable (food, fuel and packaging). Others, such as fragmented heat accumulators, remain. For Uruguay we have two references of earth ovens. Guidón [17] for the site Y-58 of Salto Grande, refers to the presence of “culinary pits”, accumulations of snails accompanied by stones. They are assigned an age of 3000 years. Consens [18] in the mound of Yacaré-Cururú recognizes several ovens formed by stone accumulations in shallow pit. He interprets them as ovens used to improve the properties of the nodes destined to make stone tools. However, these structures are very similar to those diagnosed as earth furnaces in North America (Figure 2) [15,18]

Other similarities between Laguna Merin basin mounds and the Australians mounds deserve attention. Bracco et al. [1] point out that, for the region of India Muerta-Paso Barranca, the mounds are aggregated in the areas where the flood is more extensive, where the supply of economic resources would be higher. Burned earth was characteristic of the mounds of that area, which could be explained as remnants of heat containers. It has also been pointed out that, for their preparation, anthills, biostructures like termite mounds, were used [6]. On the other hand, anthracological records [19,20] are concordant with the vegetal fuel of low caloric potential used in earth furnaces [13]. The record of silicophytoliths shows a wide use of wild plants, many of which are cooked for consumption by native groups [21,22]. Finally, it is pointed out that the mounds of the Laguna Merín, like the Australians, were elevated over centuries or millennia, manifesting themselves as the consequence of a recursive and spatially circumscribed behavior that was repeated over centuries or millennia [23-25].

Conclusion

Paleodoses estimated by TLD / OSLD of different fractions of the matrix, for the same levels of the mounds 1, 2 and 3 of the Pelotas sites, are statistically not differentiable, which allows us to deduce that the mounds’ matrix was exposed to heat. The peaks of the TL spectra indicate that the heating temperature reached at least 380°C. This allows us to infer that the mounds’ growth integrated practices that thermoaltered the matrix. The recursive use of a space for the make and use of earth ovens is consistent with this empirical evidence. The earth oven technology and the Australian mounds ovens (ethnographicarchaeological analogue) provide a framework to understand which behaviors could generate accumulations of thermoaltered sediments, and a scenario to generate hypotheses that associate technological, economic and social, as well as symbolic aspects.

References

- Bracco R, Inda H, Del Puerto L (2015) Complexity in mounds of the Merín lagoon basin and social network analysis. Intersections in anthropology 16 (1): 271-286.

- Iriarte J, Holst I, López JM, Cabrera L (2000) Subtropical wetland adaptation in Uruguay during the mid-Holocene: An archaeobotanical perspective. In: Barbara A. Purdy, Enduring Records: The Environmental and Cultural Heritage of Wetlands, Oxbow Books, Oxford pp. 61-70.

- López JM (2001) The tumular structures (cerritos) of the Uruguayan Atlantic coast. Latin American Antiquity 12(3): 231-255.

- Milheira R, Gianotti C (2018) The Earthen Mounds (Cerritos) of Southern Brazil and Uruguay. In: Claire Smith, Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, Springer Cham.

- Schmitz PI (1976) Lacustrine Fishing Sites in Rio Grande, RS, Brazil. Anchietan Research Institute, University of the Rio dos Sinos Valley, São Leopoldo, Brazil.

- Bracco BR, Panario D, Gutierrez O, Bazzino A, Duarte C, et al. (2019) Mounds and Landscape in the Merín Lagoon Basin, Uruguay. In: Inda FH, García RF, Advances in Coastal Geoarchaeology in Latin America. The Latin American Studies Book Series. Springer Cham.

- Aitken M (1997) Luminescence dating. In: Taylor RE, Aitken MJ, Chronometric Dating in Archaeology (2) Springer Science and Business Media New York pp. 183-216.

- Shrestha R (2013) Optically Stimulated Luminescence (OSL) dating of aeolian sediments of Skåne, south Sweden. Tesis de maestría (MSc) Lund University, Lund, Sweden.

- Aitken M (1985) Thermoluminescence Dating. London Academic Press.

- Vandenberghe D (2004) Investigation of the Optically Stimulated Luminescence Dating Method for Application to Young Geological Sediments. Tesis doctoral (PhD) University of Ghent, Ghent, Belgium.

- Brockwell S (2006) Earth mounds In Northern Australia: A review. Australian Archaeology 63(1):47-56.

- Jones R, Morrison M, Roberts AY (2017) The River Murray and Mallee Aboriginal Corporation An analysis of Indigenous earth mounds on the Calperum Floodplain, Riverland, South Australia. Journal of the Anthropological Society of South Australia 41: 18-61.

- Black S, Thoms AV (2014) Hunter-Gatherer earth ovens in the archaeological record: fundamental concepts. American Antiquity 79(2): 204-226.

- Thoms A (2008) Ancient savannah roots of the carbohydrate revolution in South-Central North America. Plains Anthropologist 53(205): 121-136.

- Alston TV (2009) Rocks of ages: propagation of hot-rock cookery in western North America. Journal of Archaeological Science 36(3): 573-591.

- Campanelli M, Muir J, Mora A, Griffin DCYD (2018) Re-Creating an aboriginal earth oven with clayey heating elements: experimental archaeology and paleodietary implications. EXARC Journal 2.

- Guidón N (1989) Archaeological Rescue Mission of Salto Grande, Oriental Republic of Uruguay. Ministry of Education and Culture, Montevideo, Uruguay 2(1).

- Consens M (2001) Yacari-Cururú: 18 years later. In: Uruguayan Association of Archeology, Uruguayan Archeology Towards the End of the Millennium. Annals of the IX National Congress of Archeology (I), Colonia del Sacramento pp. 115-123.

- Inda H, Del Puerto L (2007) Anthracology and Subsistence: Paleoethnobotany of Fire in the Prehistory of the Eastern Region of Uruguay. Points of San Luis, Barrancas Pass, Rocha, Uruguay. In: Marconetto MB, Babot MP, Oliszewsk N (Ferreyra Editor.) Paleoethnobotany of the Southern Cone: Case studies and methodological proposals, Museum of Anthropology FFyH-UNC. Córdoba, pp. 137-152.

- Suárez D (2018) Experimental and Paleoethnobotanical Archeology of the cerritos builders of Eastern Uruguay: an approximation from the macrobotanical register of the CH2D01 site. Master's thesis (MSc), University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay.

- Del Puerto L (2011) Weighting of wild plant resources in eastern Uruguay: rescuing traditional indigenous knowledge. Plot. Culture and Heritage Magazine (3): 22-41.

- Del Puerto L (2015) Human-environmental interrelations during the late Holocene in eastern Uruguay: Climate Change and Cultural Dynamics. Doctoral thesis (PhD), PEDECIBA, University of the Republic, Montevideo, Uruguay.

- Bracco R (2006) Mounds of the Merín lagoon basin: Time, space and society. Latin American Antiquity 17(4): 511-540.

- Bracco R, Duarte C, Bazzino A, Panario D (2017a) Monticular structures and pyrotechnology. In: Center for Scientific Research and Technology Transfer to Production - CONICET, Seventh Archaeological Discussion Meeting of Northeast Argentina, 7 EDAN, Diamond, Entre Rí

- Bracco R, Duarte C, Bazzino A, Panario D (2017b) Monticular structures, anthill and formiguers. The seduction of the analogy. In: Center for Scientific Research and Technology Transfer to Production-CONICET, Seventh Archaeological Discussion Meeting of Northeast Argentina, 7 EDAN, Diamond, Entre Rí