Debret and Public Archeology: The Tikuna Mask and the Fire of the National Museumain

Mariane Pimentel Tutui*

Master in History, University Estadual de Maringá, Brazil

Submission: April 16, 2019; Published: May 09, 2019

*Corresponding author: Mariane Pimentel Tutui, Master in History, University Estadual de Maringá, Rua Narlir Miguel, 897 - Centro. Postal Code: 18230-000. São Miguel Arcanjo, São Paulo, Brazil

How to cite this article: Mariane Pimentel Tutui. Debret and Public Archeology: The Tikuna Mask and the Fire of the National Museum. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2019; 9(2): 555757. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2019.09.555757

Abstract

The object of study of archeology is the materiality left by previous societies. For this bias, Public Archeology seeks to share and disseminate archaeological knowledge with communities involved in research. This article aims to explain the Tikuna masks, especially the monkey head, observed and designed by the French artist Jean-Baptiste Debret during the French Artistic Mission in Brazil and published in his work Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil (1834) -1839). The mask was one of the highlights of the eighteenth-century collections of the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro, which suffered a fire in late 2018.

Keywords: Debret; Tikuna; National museum; Brazil; XIX century; Public archeology

Perspective

This article aims to guide its discussions in the defense of historical, artistic and cultural patrimony and, above all, to provide a basis for a better understanding of the social issues that surround the theme of “Public Archeology” through the works of the French artist Jean-Baptiste Debret (referring to the masks Tikuna). It is hoped to contribute to the dissemination of questions and to the reproduction of critical thoughts about this theme. Before we go into the issues related to the watercolors of Debret and the fire in the National Museum, it is important to discuss public archeology. The expression “Public Archeology” [1] refers to the interaction with people, providing dialogues and discussions about symbologies and representations constituted through material culture. For this, the focus of Public Archeology is to seek greater interaction and sharing with the public about archaeological knowledge, promoting awareness in society regarding the preservation of patrimony. That is, the work in the field of Public Archeology is concerned with political and social issues, which contribute to the interest of society in scientific, economic and educational aspects. Therefore, state intervention within Public Archeology concerns aspects of legislation in terms of environmental and cultural protection. Public Archeology comes every year, reaching new possibilities and perspectives. Developing as an interdisciplinary field of study, one of its main objectives is to enable interaction with society to recover and preserve its own history (FUNARI; ROBRAHNGONZÁLVEZ, 2006, p.3).

So that the knowledge coming from academic research is not limited only to the academic environment and encompasses all publics, Public Archeology has as one of its objectives, the publicity of archaeological science. With the bonds of identity strengthened, memory helps the history lived by individuals, whose memories and ideas are generated within the communities. Therefore, Public Archeology has the social function of transmitting the public value of the archaeological heritage, seeking intense dialogues with the communities involved in projects focused on this theme. Having said that, we can enter our research object in the case of the debretian works. Jean-Baptiste Debret was born in France in 1768, nephew-grandson of François Boucher (1703-1770), a renowned Rococo master, Debret also had as mentor and teacher the master of the Neoclassical, Jacques-Louis David (1748- 1825). The French artist began his artistic studies at the Louis-Legrand High School in Paris and later at the Academy of Fine Arts. Still very young participates next to David, of the execution of the screen The oath of the Horácios [2] (work that illustrates the artistic ideals of neoclassicism). Debret also acted as painter of Napoleon Bonaparte, extolling the military campaigns, amalgamating art and politics and highlighting the battles that exalted the emperor. According to the philosopher and critic Jacques Leenhardt, Debret “left France from the French Revolution of the empire at the time Napoleon went into exile and his master Jacques-Louis David had to do the same with the arrival of the Restoration (1815) [3]”.

With the opening of the ports fomented by D. João VI in 1808, the expeditions amplify. In the meantime, Debret integrates what we call today “Artistic French Mission” [4] and brings in the tropics in the year 1816, along with other artists of solid academic background [5]. Debret was the most persistent “Mission” artist in Brazil, in fifteen years produced the most extensive documentary on historical uses, customs, sights and events in the tropics. The iconographic legacy of Debret arouses a contemporary interest, since it will incite new reflections on Brazil and not only as the Brazilians were seen by the looks of foreigners. In this context, Debret acts as painter, draftsman, engraver, decorator, teacher and set designer; hired for a period of six years as an official court artist, the artist improvises his house in the neighborhood of Catumbi, located in the capital, Rio de Janeiro. With his solid artistic baggage brought from Europe, Debret strives to make an art that maintains a bond with the reality of the country and discovers through the watercolor technique an agility in its tracing, achieving in this way a critical interpretation in his paintings.

In this period of experience in the tropics, Debret made more than a thousand images [6], among them the flag, imperial coats of arms, allegories, coins, medals, portraits of the royal family, some works of architecture, taxonomic paintings referring to native flora and fauna. The different human types also caught the attention of the artist among them: tropeiros, gypsies, paulistas, miners; also represented the Indians and their tribes, as for example, the Camacãs, the Bugres, the Botocudos, the Guaianases, the Guaicurus, the Guaranis, the Tikuna among others. There are also some engravings relating to huts and huts, masks used by some Indians, Indian hairstyles, inscriptions engraved on cliffs, scepters and vestments of tribal chiefs, ceramics, wooden and clay utensils, and some weapons such as bow and arrow. The artist also describes the different vegetables used in food, necklaces and tattoos made by Indians (yams, cipó, aipim, urucu, genipapo, among others).

In 1829 Debret organizes the first public art exhibition in Brazil, paying from his own pocket the edition of the catalog with 115 works. The artist participates in the hall with ten works of his own, including the ceiling design of the Hall of the Academy.

The following year occurs the second hall and Debret is elected corresponding member of the Academy of Fine Arts of the Institute of France. 1831 is the year of his departure, the painter leaves Brazil and returns to Paris, where he receives decorations in the following years. He was unanimously elected as a titular member of the Institut Historique de Paris (1834), admitted as a corresponding member of the Historical and Geographical Institute of Brazil (IHGB) in 1840, decorated with the Legion of Honor in the official degree (1841) and made an honorary correspondent of the Academy of Fine Arts of the Institute of France (1842). The watercolors served as a basis for the engravings that the painter gathers and publishes in album format between 1834-1839, as soon as he returns to Europe. It is a written and illustrated work elaborated during the fifteen years lived in Brazil, with the title: Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil, constituted by three volumes, the first one being launched in 1834, the second in 1835 and the third and last volume in 1839. Debret intends to show readers a vision beyond the simple idea of an exotic and distant country, which was the interpretation given by Natural History and taxonomists.

Through minute details, the artist attempted to create a work both historical and cultural, since it represented simple people and different aspects of culture, religion and daily life in Brazil. In a total of 153 boards accompanied by texts, the artist elucidated his perceptions since he had landed in Guanabara Bay, Rio de Janeiro, in March 1816. In the first volume of Voyage Pittoresque (published in 1834), Debret depicts native vegetation and Indians, in the second volume (1835), slaves and urban work, and in the third and final volume (1839), festivals, traditions and cultural manifestations. It is important to emphasize that the recognition of all debretian work, as well as its prestige in Brazil, has been delayed due to the arrival of the photograph and also to the criticisms inserted in the Brazilian Historical and Geographical Institute (IHGB) [7]. It was not until 1940 (one hundred years after it was released) that Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil arrived in Brazil. In the first half of the twentieth century, discussions of nationalism, conducted with the modernist movement, brought to the forefront the interest of researchers and art collectors for the works of the past, which influenced the formation of large collections. It is in this context that we will explain about the Tikuna masks, especially the monkey head, observed and designed by the French artist and published in Voyage Pittoresque et Historique au Brésil.

According to Bandeira, Debret could not observe the Indians in their wild habitat and most of the details in their engravings and watercolors were copied from the work of other traveling artists [8] or objects preserved in the Museum of Rio de Janeiro. Thus, Debret had to use the observations of his predecessors, such as the naturalists Spix and Martius [9] and of the prince Maximiliano de Wied [10] . In the opinion of Bandeira and Lago, still the artist leaves us an interesting and valuable record regarding the Indians.

Among the indigenous artifacts that Debret represented in his watercolors, published in lithographs [11] colored in Voyage Pittoresque, we chose the masks, especially the Tikuna people.

The Tikuna are Amerindian peoples who traditionally live in a contiguous region comprising part of the territories of Brazil, Colombia and Peru. Their villages are on the banks of the Amazon River - Solimões and in sites located along tributary rivers. According to data from the Instituto Socioambiental (ISA) [12], are one of the largest indigenous groups in Brazil. The Tikuna speak an isolated language, their first recorded references in the Amazon region were by Cristóbal de Acuña (1597-1670), a Jesuit priest and clerk of the expedition of Pedro Teixeira, carried out from Belém to Quito in the years from 1637 to 1639. The contact of the Tikuna with the non-Indians occurred from the second half of the seventeenth century, intensifying in the late nineteenth century, when much of their land was occupied by rubber farmers and traders who lived from the extraction of rubber.

The Tikuna call themselves Magüta people, which means “people fished with stick.” According to oral tradition [13], the origin of the Tikuna begins when Yo’i (mythological hero) fishes them in Igarapé Évare, located in the sources of Igarapé St. Jerome (tributary of the left bank of the river Solimões) and considered as a sacred place.

Among the sacred rituals performed, many authors consider the Ritual Da Moça Nova [14] as being one of the most important for the Tikuna due to its complexity and richness of details. The use of masks in initiation rituals in autochthonous populations signifies a kind of masculine cultural response to the powerful process of female transformation. In Tikuna society, the making of masks and their use, as well as musical instruments, are the exclusive domain of men. From the perspective of the anthropologist Jussara Gomes Gruber [15], the accounts of ethnological travelers have always been with their attentions turned to ritualistic masks; the effect of these masks on the eye of the observer is evident in the ethnographic collections of museums both in Brazil and abroad. The predominance of such artifacts in relation to the other items of material expressions attests to the propensity to focus on a product that, from the point of view of the collectors, was the most representative of the Tikuna culture.

Jean-Baptiste Debret observes and draws the Tikuna masks, later publishing them in the first volume of Voyage Pittoresque (1834). In her iconographic studies on the set of debretian works, the historian Valéria Lima establishes a double interpretative method for the analysis of the works of the artist. The first is to carry out a clash between the works and the text produced by Debret and the second asks for a look capable of investigating the iconography, seeking not only the verisimilitude of the works, but also the relations with the images produced by other travelers and the history of art in general. It is from this analysis that Lima demystifies the generic category that Debret is a “traveling artist”. In the case of a very delicate bias, the historian is attentive to the terms. The main themes of his watercolors include the daily lives of slaves and urban habits, exactly what differentiates the French artist from other traveling artists. Moreover, contrary to travel accounts, Debret’s work follows a pre-established program and not a chronological line as usual, ie for Lima, Debret does not make a travel account but a work of historiographic, due to the artist’s classificatory intention in selecting, organizing and classifying groups. As an example the historian cites the separation of indigenous groups according to the familiarity with the Europeans, highlights the steps of approach and understanding by the slaves of the civilized habits, among other resources used by Debret. Another factor that would disqualify the artist from a traveler in the traditional sense would be the fact that Debret lived for fifteen years in Brazil, having a regular job as a painting teacher and as an official court painter.

On the different types of masks, the French artist describes on plate 39: It was only in truth that the industrious savage man, having exhausted all the resources of the tattoo, in order to become horrible, to manufacture animal-shaped masks of all kinds, the only means of physically reproducing the appearance of a more frightening monstrosity , and therefore worthy of all the admiration of the spectators on the feast days. It is what he did, and still more: not satisfied with this partial transformation, he was able to take advantage of the advantage of a long dress and a head to become a giant, in which his always active genius, rivaled that of the European couturiers (DEBRET, 2016, p.127). Still on the masks, Debret describes that “These gross imitations, really barbarous but executed with great care, present some degree of similarity with the object they must represent.”

In the production of the masks, Gruber explains that the Tikuna used the weeds of some Amazonian trees and the ornamental motifs could be distributed over the entire dress. In the head, the decoration served to emphasize the features of the supernatural entity, but it was in the weaving that covered the body and observed a greater number of drawings. These drawings could imitate the skin of the entity represented or possess a more abstract stamp belonging only symbolically to a supernatural category. According to the author, in fact, the masks represent fear, the forces of nature, the legendary and ancestral animals, the sacred, the forces unknown, the phenomena of nature, the places, finally, the elements and values of culture Tikuna. Among the artist’s descriptions, we find reports on jaguar, tapir, armadillo, winged human and plume, fish and monkey masks.

These ornaments of great importance are as light as solid, for they consist of a very thick cotton cloth, strongly gummed on both sides and painted next, which gives them the consistency of a hard and sonic body. The different colors employed are white, light yellow, red, brown and black (DEBRET, 2016, p. 127). Second, to decorate the masks, the Tikuna used a huge set of figures almost always represented in a naturalistic way and inspired by the regional fauna, with colorful colors obtained by a varied range of paints and extracted from natural resources, such as: saffron rhizome (for obtaining yellow); bure leaves (light blue); fruits of the pocova (black or dark blue); leaves of peach palm (green); Urucu (red); Brazilian Bark (light red and pink) [16].

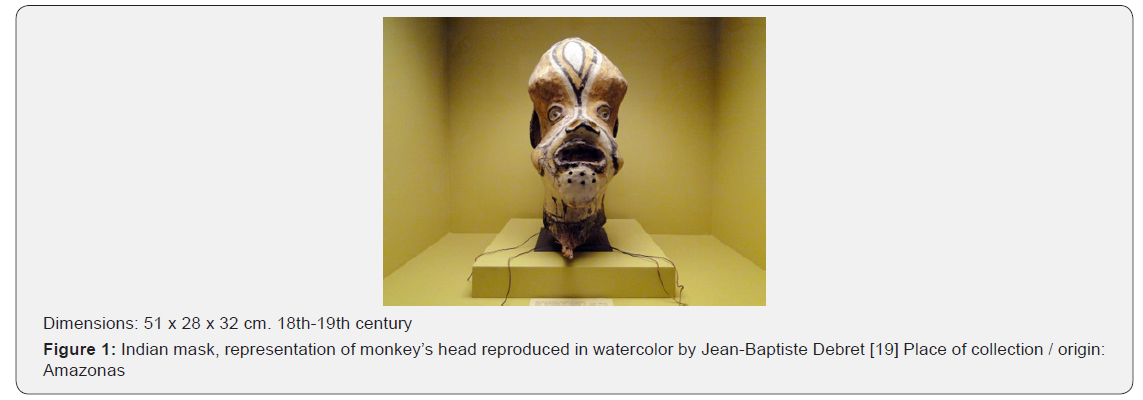

In addition to the drawings of single masks, Debret also shows a complete scene performed in watercolor. From the perspective of the foreigner, it would be interesting to show the wild fun, so that we had an idea of the use of the masks in similar occasions. These masks belong to the collection of the Imperial Museum of Natural History [17] of Rio de Janeiro, where I designed them; attributed them to the Indians of Pará and, in fact, present the same character as those enjoyed by Spix and Martius among the savages Tacunas [18,19]. We observe in Figure 1 the monkey head mask of the Tikuna observed by Debret and that composes the representation of the Ritual of Moça Nova. One of the highlights of the nineteenth century collections of Brazilian indigenous ethnology from the National Museum in Rio de Janeiro, which suffered a fire at the end of 2018. The National Museum is located in the historic Palacio de São Cristóvão, in Quinta da Boa Vista, originated as a colonial institution, and its history was intertwined with that of the Brazilian nation. It is the scientific institution and the oldest museum in the country, having completed its bicentennial in 2018. On September 2, 2018, a fire of enormous proportions took over the museum destroying thousands of years of history of Brazil and the world [20], among the items consumed by the flames, were over 40,000 indigenous artifacts, including this Tikuna mask.

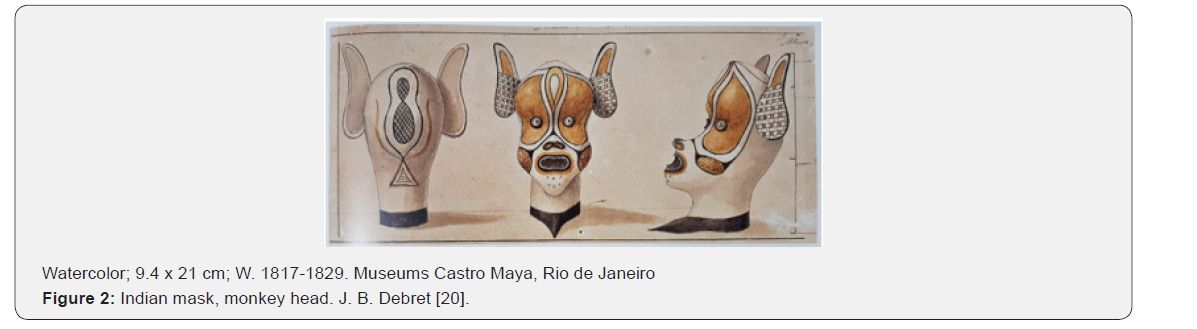

The fire also destroyed a wealthy Amazon ethnographic collection of the nineteenth century that was in the basements of the traditional institution. The pieces that compose this collection were collected by the poet, lawyer, journalist, ethnographer and Brazilian theatologist Gonçalves Dias (1823-1964), who was part of the Scientific Commission of Exploration for the Universal Exhibition held in Rio de Janeiro in 1861. The collection was extensive and featured pieces from various Amazon peoples, such as arches, pieces, wooden benches, the production of ornaments with bird feathers, pots, baskets, pottery, ceramics, among other items. After the exhibition, this collection was transposed to the National Museum and has never been studied, remaining in the cellars [21]. Jean-Baptiste Debret observing the Tikuna mask, recreates the same object in watercolor. As we observed in Figure 2, the French artist represents the mask from various angles, indicating in the drawing up to the height of the object and maintaining the colors reliable if compared to the original piece.

The watercolor has the fastest drying and allows, through thin transparent and superposed layers, to capture with agility a detail among other minutiae found by Debret. It is valid to emphasize that an image is not the reflection of the real but what is perceived and passed to the paper from the perspective of the artist, which is inserted in a certain universe. The art historian Jorge Coli calls attention to the importance of gaze as one of the most fruitful attitudes for the study of our artistic heritage of the nineteenth century. The look is primordial for the art of any period and any country, in particular for the nineteenth century, emphasizes the historian. That said, we can say that the relation of the spectator to the image encompasses a series of “events”: temporality, imagination, memory, history, perception, dialogue, affection, culture. Like a reader, the spectator, when observing an image, initiates a dialogue with the object and the awakening of the senses. In this way, in order to cross our gaze in the face of the works, we raise questions that point to instigating aspects for the reflection of the historian who intends to work with iconographic sources, that is, the world in which it inserts and translates, and the perspective that the same builds and reveals.

Final Considerations

The process of knowledge of the ritualistic masks of the Tikuna peoples began, we became aware of the importance of the mythology of the indigenous peoples, not in their figurative sense, but as these groups experienced it as a sacred experience, constituted by all the knowledge transmitted from generation to generation generation. According to the anthropologist and philosopher Claude Lévi-Strauss [22], it is through masks that the music and mythology of a given culture reach a symbolic approach. In relation to watercolor, located in the [23] of the Museum of the Chácara do Céu (Castro Maya Museums) in Rio de Janeiro, undoubtedly the legacy left by Debret opens many possibilities for us to read on the part of the History of Art and Cultural History, fields that have been firmly established in Brazilian historiography contemporary art. About the image, its concept as representation encompasses a series of assumptions between time, the object of observation and the observer. Reading an image always presupposes starting from restlessness, values, inquiries; which thus create possibilities for interpreting and reading the images. We must emphasize the importance of this work as an essential part of our history and our identity: a rich material referring to nineteenth-century Brazil that offers a new impetus for current and future research.

Faced with the catastrophe in the National Museum [24] , a tragedy not only for the Amazon and for Brazil, but for the world, it is even more important to reinforce the discourse of struggle and safeguarding before our collective memories. The fire of the museum reflects the neglect with the national patrimony, science and technology; besides revealing to us the lack of policies of preservation of the artistic, material and documentary patrimony in Brazil. It is necessary to safeguard the Tikuna culture and the caution of the debretian works, along with our history and memory. It is urgent that we need to denounce these issues both through history and through public archeology, for “a people without memory is a people without history. And a people without history is bound to commit, in the present and in the future, the same mistakes of the past [25-42]”.