Inca Mortuary Practices. Material Accounts of Death in Quebrada De Humahuaca at the Time of the Empire

Agustina Scaro* and Clarisa Otero

Instituto de Ecorregiones Andinas (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas-Universidad Nacional de Jujuy). Av. Bolivia 1239, San Salvador de Jujuy, CP4600, Jujuy, Argentina

Submission: April 05, 2019; Published: April 25, 2019

*Corresponding author: Agustina Scaro, Agustina Scaro, Instituto de Ecorregiones Andinas (Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Tecnológicas-Universidad Nacional de Jujuy). Av. Bolivia 1239, San Salvador de Jujuy, CP4600, Jujuy, Argentina

How to cite this article: Agustina S, Clarisa O. Inca Mortuary Practices Material Accounts of Death in Quebrada De Humahuaca at the Time of the Empire. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2019; 9(1): 555751. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2019.09.555751

Abstract

This contribution has the purpose of presenting a set of material evidences linked to mortuary practices from Inca times recovered in Esquina de Huajra and Pucara de Tilcara archaeological sites. This in order to ponder the role of funerary practices in the social life of loca populations under Inca control. The presented contexts refer to diverse practices pointing at the great variability regarding the treatment of the deceased during Inca times, allowing to analyze the new socio-political context established in Quebrada de Humahuaca. The funerary practices registered refer to a strong tradition linked to the cult to the ancestors, probably rooting from pre-Inca moments. As in other Andean cases, these manifestations could have responded to beliefs associated with the regeneration of crops and productive cycles in general. The role of the deceased in strengthening the collective memory and the meaning of traditions shared throughout time is also relevant.

Keywords: Mortuary Practices; Material evidences; Inca domination; Quebrada de Humahuaca

Introduction

The analysis of mortuary practices allows us to approach several aspects of the societies in which they occurred, reflecting not only the memory of the group but also the socio-political and economical processes of it. In the case of the Andes, it has been stated that the cult to the ancestors has strongly molded the way of conceiving death and treating the deceased [1-4]. Thus, the body or parts of the deceased would have functioned as referents of the ancestor, in charge of keeping the well-being of the community. This contribution has the purpose of presenting a set of material evidences associated to mortuary practices from Inca times recovered in the archaeological sites of Pucara de Tilcara, located in the central sector of Quebrada de Humahuaca (Jujuy, Argentina), and Esquina de Huajra in Quebrada’s south-central sector. This, with the objective of analyze the role of funerary practices in the social life of local populations under Inca domination. Although being located in the same region and being contemporaneous, Esquina de Huajra and Pucara de Tilcara present characteristics that differentiate them in their spatial and functional organization as well as mortuary evidences. The presented contexts refer to a diversity of practices signaling a wide variety in the treatment of death during the Inca period, allowing us to analyze the new socio-political context established in Quebrada de Humahuaca.

Quebrada de Humahuaca and the Inca Domination

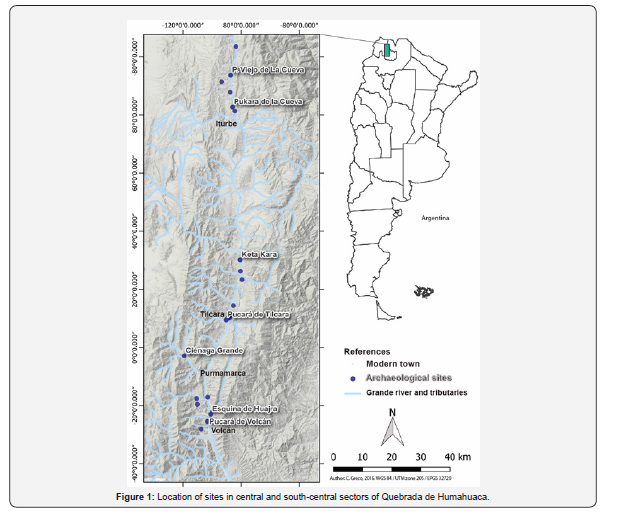

Quebrada de Humahuaca (Figure 1) became part of the Kollasuyu, the southern province of the Inca Empire, during the first half of the 15th century. A series of indicators, as the presence of artifacts and Inca architecture, the network of roads, garrisons and tambos, refers to this conquest in the Argentine Northwest [5-8]. Williams [6], following González [5], proposed that the Inca political organization was flexible, presenting notable variations between several conquered regions, given that imperial administration was built over pre-existent political systems, making use of an ideology based on reciprocity and local redistribution of resources in order to legitimate the newly established economy (Figure 1).

In this sense, the Empire established several conquest strategies that included both diplomacy and violence, and strategies of power consolidation, linked to a long process of integration of the dominated groups. The characteristics of the Inca occupation in the region depended, as mentioned by Cremonte & Williams [9], on the degree of political centralization of the ruled societies and their acceptation or resistance to the domination. The existence of important settlements both in places with presence of local population as well as in “empty areas” would evidence, according to Williams & D’Altroy an occupation of selective intensity in strategically located productive areas. This would indicate that the Empire designed its way of government regarding local situations but always having in mind a largescale planning, favoring at the same time certain ethnic groups and using local elites in order to help establish and maintain the government. The presence of ethnic groups favored above others would be evidenced by the circulation of certain ceramic styles in parallel to the Inca Imperial style, as in the case of Yavi Chico, Inca Pacajes or Inca Paya [6].

The main policies of the Inca government for the conquest of the South-Central Andes included the installation of fortresses in the oriental border and the establishment of a vial network, the installation of imperial centers, the intensification of agriculturalherder and mining production, and the claim of sacred spaces by means of the construction of high shrines [6,7,10]. Although we do not observe a state infrastructure as ambitious as in the northern regions of the Empire, these policies were executed by means of sophisticated strategies, as we mentioned before, adapting themselves to the local variations in each region. These strategies generated changes in the use and significance of public, domestic and ceremonial spaces, since they included military control, ideological claims, demographic relocation, and agricultural-herding and mining intensification, but also the ceremonial hospitality and the preferential treatment of certain conquered groups.

In the Argentine Northwest, the Inca empire created four provinces, of which the northernmost was Humahuaca, whose capital would have been constituted in Pucara de Tilcara. Towards the south, the provinces of Chicoana with its capital in La Paya, Quire Quire with its political center in Tolombón, and the Southern province with its center in Tambería of Chilecito would have been located [11]. In Quebrada de Humahuaca, state policies are visible through the presence of remodeling in the conglomerated settlements established in the previous period, called Regional Developments Period (1000-1410/1430 AD). Among these sites we can identify La Huerta [12-14], Campo Morado [15], Pucara de Perchel [16], Pucara de Tilcara [17-20] and Pucara de Volcán [21-24]. Thus, the main administrative centers where established in most of the pre-Inca sites of the region [12,25]. Remodeling of previous sites in charge of the state administration would be linked to the Inca recreation of the conquered community’s landscape, where architecture could have functioned as a symbolic act of territory appropriation based on a double-end game of integration and segregation between the local and the imperial [26,27].

The landscape remodeling performed by the Empire meant the total or partial abandonment of some sites such as Los Amarillos [28], reinforcing the changes introduced by Inca administration in the pre-existent landscape. The case of Los Amarillos considered as the political center of the Omaguacas ethnic group [29-34], could indicate, as suggested by Nielsen [28,35], that the Incas reorganized pre-existent social and power relations in Quebrada de Humahuaca. As mentioned before, Pucara de Tilcara would have been the political-administrative center of the Humahuaca’s province, registering during these moments the largest occupational density in the settlement, reaching a complete coverage of the mountaintop where it is located, of about 17.5 hectares [20]. The findings in Pucara de Tilcara lead to its consideration as one of the main productive and administrative poles of the region, in which numerous artisan workshops destined to specialized manufacture of goods in metal, shell and stone would have been situated [8]. Likewise, the possibility of expanding the settlement as well as the proximity to Alfarcito’s agricultural fields and alabaster, limestone and copper quarries could have been the main causes behind the Inca’s usage of Tilcara for the installation of a large productive center. In addition, the finding of materials with a clear Inca affiliation, as the Inca Imperial pottery, may account for a state organization strongly linked with local populations [36]. Among the studied contexts for this site, we recognized these forms of articulation mainly within ritual practices involved in the cult to fertility and the ancestors. Burials and other evidences manifesting different types of mortuary behaviors express a plurality of events where social hierarchies within a state political frame could have played an important role. In other sites of the region, as in the case of Esquina de Huajra, we also distinguished this variety of practices, which are exposed below.

Esquina de Huajra

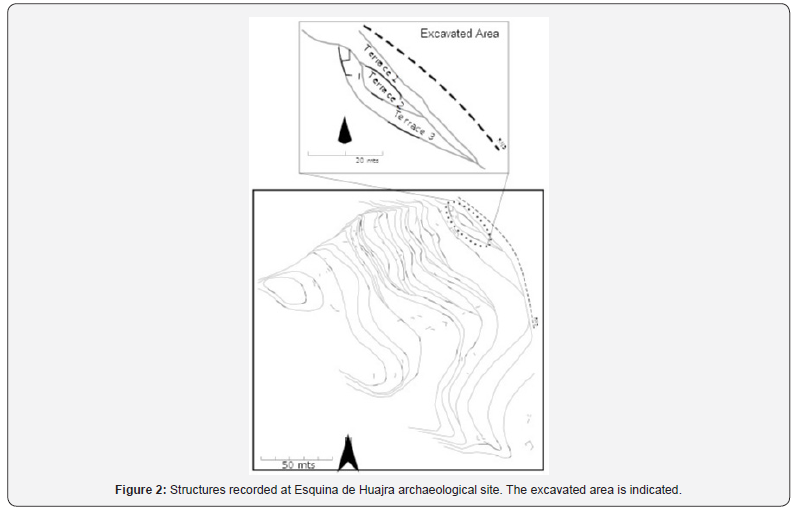

Esquina de Huajra (Figure 2) is a late Humahuaca-Inca settlement located in the south-central sector of Quebrada de Humahuaca, in a space not previously occupied by local populations [26,37,38]. Nine datings obtained in this settlement allowed us to delimit its occupation to nearly two centuries, encompassing Inca and Hispanic-Indigenous Periods [39]. Although the occupation of this site would have lasted until the Hispanic-Indigenous Period, we have not registered any Spaniard elements. It is a clearly Humahuaca-Inca context that does not show any of the typical features characterizing other contemporaneous assemblages, with clear differences for example, with the cemetery of La Falda de Tilcara [40,41] (Figure 2).

So far 222 m2 have been excavated in three levels of terraces. The inferior level, called Terrace 1, corresponds to a domestic area, probably the patio (external area) of a house where a sector directly destined to food preparation, storage and consumption would have existed, associated with a hearth, grinding tools, camelid remains and fragments of different vessels, as well as tableware. The presence of a spindle with its whorl is an indicator of textile activities, while the obsidian cores and flakes point to reduction tasks for the obtainment of lithic instruments. The incidence of foreign ceramic pieces in this terrace is remarkable, especially from the highlands, as well as the deployment of forms, surface treatment and finish, and fine pastes in tableware. These elements, added to the presence of polished aribalos (typical Inca vessel used to store alcoholic beverages such as chicha) and standing pots, would refer to a context of status and interaction, allowing us to suggest that Esquina de Huajra functioned as a strategical and special settlement. The intermediate level, called Terrace 2, presents a few contention walls and its excavation did not allowed the identification of a clear occupational floor. Finally, Terrace 3 conforms a burial area, where we found the funerary contexts analyzed in this opportunity.

The funerary contexts in Terrace 3

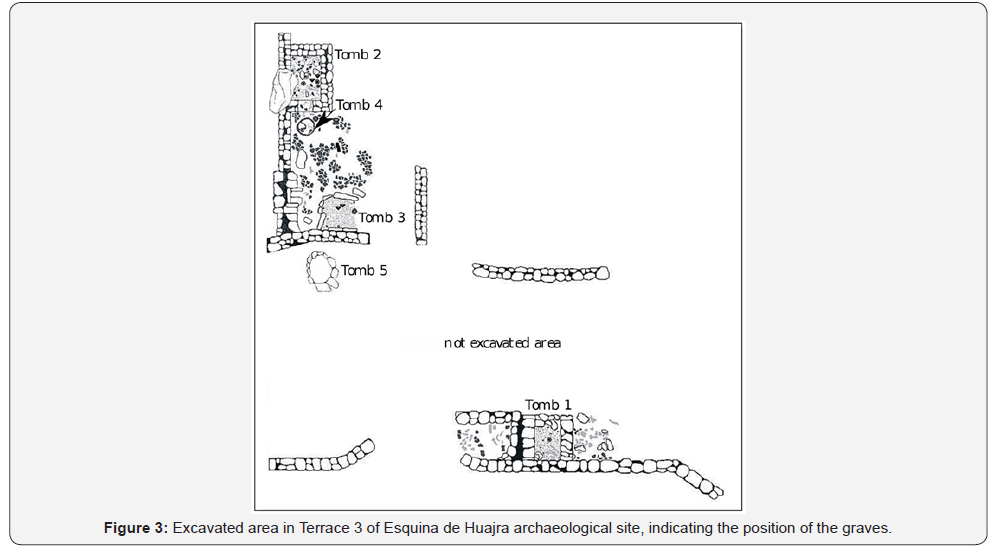

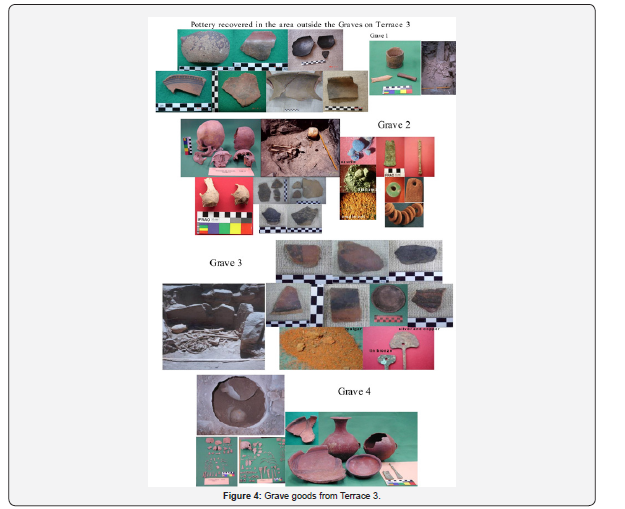

Until now, four burials have been excavated in Terrace 3, as well as a sector outside the graves (Figure 3). In this space, we have recovered fragments of polished dishes, plates and bowls with and without decoration, associated to pots, aribalos, jugs and jars both ordinary and decorated with local and non-local styles. At least five large ordinary restricted vessels were registered, probably used for moving beverages such as chicha and solid or semi-solid aliments from the domestic units. These vessels were associated to metal and stone instruments, flakes and three likely lithic ornaments, among which a mica plate with a central orifice stands out (Figure 3).

In the external area, polished bowls are more abundant that within the domestic area (Terrace 1), indicating the individual consumption of liquid aliments. Little plates, also more abundant and varying regarding shape and decoration, would indicate a similar behavior but for the case of solid aliments. Preparation and storage vessels appeared in less quantity and variety that inside the domestic area, especially in the case of pots. The better finishing of vessels and the larger proportion of decorated pieces in this sector would indicate that, for its use in this sector, people selected the local pieces with better termination. These evidences allow us to suggest that the sector external to the graves could have been an area where individuals could congregate for the preparation of burials and the corresponding funerary rituals (Figure 4). The scarcity of preparation and storage vessels reinforce this idea, indicating the non-domestic functionality of this sector. Given the fact that we are referencing a reduced space, we consider that the sector external to the graves could have reunited a small number of individuals directly participating on funerary rites (Figure 4).

The graves exhibit variations regarding constructive techniques, burial modalities and mortuary goods. Tomb 1 is a rectangular chamber constructed over the surface containing the remains of four adult individuals and a perinatal, conforming a secondary burial (Figure 4). The grave goods consisted on a small ceramic vase and ordinary fragments corresponding to one or two vessels, a little lump of red pigment, a flattened and smoothened plaque of schist, a bone projectile point manufactured on a camelid metapodium, as well as a bone tube. Tomb 2 is also a chamber constructed over the surface but in this case an entrance was registered (Figure 4). In this secondary burial the remains of seven individuals were recovered. They were accompanied by almost 100 necklace beads made of bone, carbonate rocks, black lutite and turquoise, fragments of a tweezers and a pendant of tin copper, two lumps of blue pigment composed by ground azurite, atacamite green powder and oropiment yellow, as well as two skulls of Muscovy duck (Cairina moschata s.p.). Recovered pottery includes fragments of nearly 14 local and non-local ceramic vessels and a small Humahuaca Black-on-Red style dish, probably used for the offerings of solid or semi-solid aliments.

The grave goods found in Tomb 2 are significant due to the symbolic value of the ornaments, colored powders and duck skulls. The scarce presence of pottery and its fragmentation degree allow us to suggest that these could have been the remains of the vessels offered in the primary burial that with the subsequent manipulation of the remains, probably in one or more rituals, could have fractured and being replaced by other elements. Tomb 3 corresponds to a semi-circular chamber constructed above the occupational floor (Figure 4), in which the secondary burial of a woman of approximately 40 years old was found. The grave goods consisted of a black polished dish, some camelid bones, fragments of about six ceramic vessels corresponding to different local and foreign styles, as well as two metal topus (pin decorated at one end, used for holding clothes), one of them manufactured with a silver and copper alloy that would not be local. Scattered among the bones orange realgar powder was also found.

The elements integrating this woman’s burial would reflect gender and social or ethnic identity distinctions. The topus were symbols clearly related with the feminine in Inca times and until

the Early Colonial Period, serving as gender indicators. The fact that at least one of them was non-locally manufactured and the presence of Yavi-Chicha and Casabindo vessels from the highlands allow us to think that the buried woman was native of the Western Jujuy’s Puna or that she had strong bonds with that area. Tomb 4 was the only primary burial found, located in the interior of a large vessel that was interred in the floor of the external space to the tombs (Figure 4e). Inside the vessel, the remains of a 7 years old boy and a perinatal of 38-40 gestation weeks were found. The grave goods that accompanied the infants included two chisels and fragments of a tweezer, all manufactured in tin bronze; two pink polished aribalos and two Humahuaca-Inca bowls. The elements composing the grave goods of Tomb 4 would be expressing the idea of Andean duality, manifested in several organizational aspects of this society [42-44]. In this case, there are two children of different ages, buried alongside two bowls, two aribalos and two chisels. The fact that these elements were also of different sizes -one larger and one smaller-, allow us to suggest a correlation between the age of the children and the size of the objects conforming the grave goods. Thus, a network of meanings between the children, the bowls, the aribalos and the chisels could be established. These would be expressing the dual world-view of the groups to which these children belonged, as social practices that could manifest in different circumstances and diverse materialities.

Three of the tombs were found in structures built above the occupational floor. This situation expresses a change in contrast with the previous local funerary pattern, which consisted in tombs located under the floor of domestic units. Besides, these three tombs consist on secondary burials -that in two cases are ossuaries- containing the remains of several individuals of different ages. This situation would evidence the manipulation of human remains in periodic re-opening of the tombs. Therefore, we argue that a space for the veneration of the ancestors may have emerged in Esquina de Huajra, constituted by an area of congregation of few individuals directly in charge of mortuary rites and by stone chambers that would have had a high visual impact not only in the settlement but also in the surrounding areas.

Pucara de Tilcara

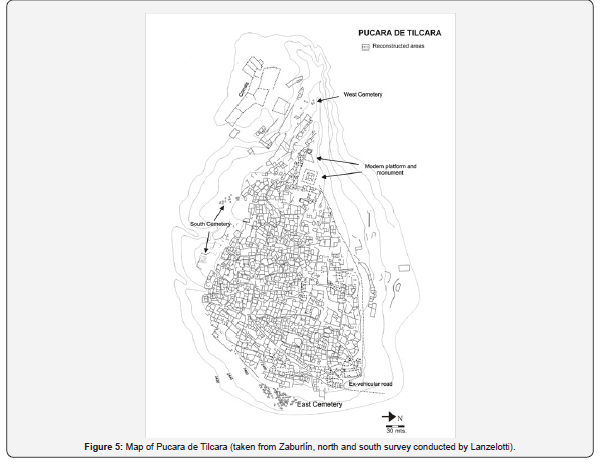

This archaeological site, located in the central sector of Quebrada de Humahuaca (Figure 5), is known for being the largest pre-Hispanic settlement in the region. The beginning of its occupation corresponds to the 12th century, but it is during Inca times when the settlement’s size increased as a consequence of an accelerated rise in population density. As a result, several structures were remodeled and terraces were expanded to build new houses and workshops [20]. The approximately 580 detected structures allow estimating that the site could have housed more than 2.500 inhabitants dedicated to diverse productive activities and in some particular cases administrative tasks. The architectonic features of some buildings and the importance of the objects found in them led us to believe that an important number of religious leaders linked to the Empire may have lived in Pucara de Tilcara (Figure 5).

The settlement apparently functioned as the capital of the Inca province or wamani of Humahuaca. Besides fulfilling political functions, as its mentioned by González & Williams [46], this was an important productive center. The recent excavations carried out in eight sectors of this site and the review of materials recovered during the early 20th century that are currently preserved in three Argentinian museums, allowed to detect over 50 metallurgic and stone workshops. These workshops can be defined as houseworkshops, since evidences pointing out towards both domestic activities and multi-artisanal production [47] destined to the specialized manufacture of metal and stone goods.

Tombs in Housing Unit 1

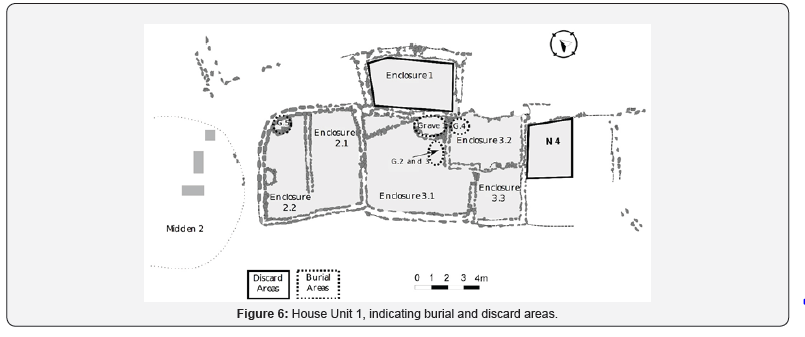

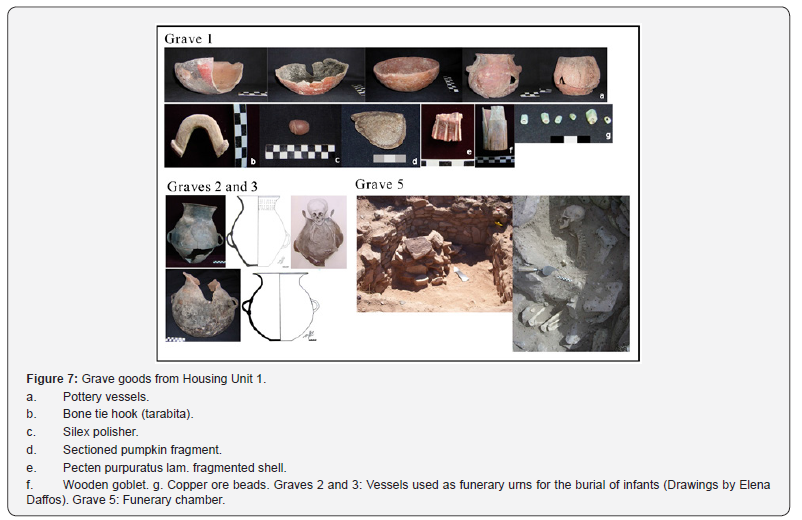

Housing Unit 1 (Figure 6) is one of the house-workshops that provided the most information about the artisanal labors, since it was intervened with modern excavation techniques, uncovering almost its total surface [48,49]. This unit represents a house located in two terraces of the inferior extreme in the Pucara’s southwestern foothill, known as “Sector Corrales”. The excavation of four of its enclosures and two patios, covering 127m2, revealed a continuity in its occupation, between the 13th century and the late 15th century or maybe beginnings of the 16th century AD [50]. This house-workshop, destined to metal objects production during the Inca domination, was abandoned as a productive and housing space in order to be used as a graveyard. Five burials were detected within the central and lateral patio [20] (Figure 6). Built above the occupational floor of the central patio, Grave 1 (G1) constitutes an ossuary (Figure 7). A curved wall attached to the perimeter of this patio was used for its construction. The dimensions of this chamber (1,6 meters wide x 1 meter long) indicate that it was built with the purpose of burying several individuals, of which 11 adults and 10 immatures were identified [51] (Figure 7).

It was possible to distinguish a first burial event, corresponding to an infant, whose remains were articulated and covered with a thin ash layer [52], and was accompanied by a copper and aragonite beads, as well as by materials that are not frequently found due to conservation issues, as a wooden beaker conserving pigments and fragments of wood and calabashes recipients with red paint impregnations and a siliceous polisher. Subsequently, the second phase took place as a secondary burial where several human bones were placed, massively and intermingled. Theses bones were also covered by numerous and successive ash and charcoal lenses, which served as ritual marks for distinguishing each burial event. Among these human remains fragments of ceramic pitchers and bowls, a fragment of spatula or loom stick, camelid bones, pieces of wood -some of them shaped as shafts with remains of red painting-, remains of molds for the production of metal objects using the lost wax technique, over 40 calabash fragments -probably used as liquid containers-, pigment’s lumps of several colors and a bone tarabita (a tie hook) used for tying a funerary bundle were detected as mortuary offerings. The ceramic pieces deposited as grave goods show evidence of a previous use. This situation also appears among restricted vessels used as urns for the burial of two infants along the eastern wall in Enclosure 3.1, denominated Graves 2 and 3 (G2 and G3). They were located alongside the eastern wall of the patio and lineally to G1, and they may have been contemporaneous to the first moment of use of the chamber (Figure 7). Grave 2 corresponds to the burial of a 3 years old infant with a tabular cranial deformation [52], placed inside an “Angosto Chico Inciso” pot that was longitudinally fractured. This pot presents abundant soot in the surface, especially in the lower body and base, demonstrating its previous use for cooking foods expose to long terms fire as arrope.

The burial identified as Grave 3 corresponds to an infant of approximately 3 months old placed inside a large ordinary pot with evidences of fire exposure. This pot was placed vertically without its base, which was probably sectioned for introducing the infant, since the opening of the vessel does not exceed 15 cm in diameter. The opening was sealed with a mud layer and the base of a pitcher was placed above it as a cover, in such a way that its internal surface was exposed. Inside this base, large amounts of soot were registered, suggesting that it was used for burning offerings. Grave 4 was identified in the Northwestern corner of Room 2 in Enclosure 3. It also corresponds to the burial of an infant that was placed over the floor of the room. In this case, several bones of the skeleton were missing, possibly as a consequence of a subsequent extraction or maybe due to the context’s perturbation caused by the falling of the supporting wall located in the upper step. Part of these remains was found covered by a layer of consolidated mud and surrounded by ashes. Three ceramic pieces were identified as grave goods. A Fifth grave (G5) was located in the Northwestern grid in Enclosure 2.2 (Figure 7). In the Northwestern corner of this patio, about 10 cm below the surface, the skull of an adult was found. After cleaning this context, it was confirmed that the skeleton was complete. This is the reason why we argue that it was a primary burial, in which the body was deposited in fetal position inside a 1 x 1meter stone chamber, partially fallen at the moment of excavation. The collapse of this structure must have occurred when the remains of this individual, identified as an adult woman, still conserved its soft tissues. The skeleton is articulated, so it must have fallen over its left side and its lower limbs remained underneath the rocks forming the eastern lateral wall of the chamber. The occupational floor was cleaned in order to build this mortuary structure, such as Grave 1.

The falling of this structure must also have affected the disposition of materials found associated to this woman, some of which must have been included as grave goods [53]. On one side, along the skull a red pigment lump was found and beneath the pelvis a projectile point with notched base. Once the set of stones conforming the burial was removed a small lens of ashes, dispersed carbons, burned camelid bones and a shallow hole were detected. These evidences could indicate the placement of offerings and the preparation of the floor for the burial by means of burning and smoking (sahumado) the context. From this hole, we extracted wood remains, among which we identified fragments of a spoon handle, and a tube manufactured on a bird bone. Several bone alterations were identified in the bodies of the buried adults, accounting for pathologies of postural origin and periodic stress probably associated to artisanal activities carried out in this Housing Unit.

Other aspect demonstrating the link between the deceased and the development of artisanal activities in Unit 1, and that in turn highlights the filiation with the individuals that occupied it, is the kind of offerings included as grave goods and the ritual practices that honored them, even in moments well after their burial. Regarding the type of grave goods found, it is worth mentioning once again the finding of a beaker with pigment remains inside, pigment lumps, wood remains with red paint impregnations and the siliceous polisher found at the base of Grave 1, all of them making clear references to ceramic production. These findings are complemented by the identification of a Humahuaca Black-on- Red small pitcher, which appeared outside this chamber, buried in proximity to the foundations of the structure. Inside this small pitcher with sectioned neck, three siliceous polishers were found, likely deposited as an offering.

The only indicators of metallurgic activity detected are the remains of molds and the powder with content of copper, which were included as grave goods. The numeric difference between these materials and those linked to ceramic production could indicate that the primary activity of this housing unit was pottery. Thus, the assemblage of grave goods could be considered as sensible signs or informational material components about the personality of each buried individual. From the moment in which polishers and pigments, among other materials, were included in these funerary contexts, they lost their “neutrality” and transformed into attributes corresponding to particular individuals [54]. Different kind of objects, from those previously used in artisanal activities to ceramic pieces used daily for the processing and service of food, were re-signified by their introduction in a sacralized and ritualized context. Despite the fact that in some cases they continued playing their roles, as sharing, serving and containing aliments, they must have acquired a new symbolic value by being used for a different type of consumers: the deaths. This new form of consumption must not have been a destructive act, considering that death was not imagined as a definitive end.

The bond between the living and the deaths that occupied Unit 1 must have also symbolically endured through time, renovated by conducting commemorative events after the house abandonment. The finding of a small pitcher that, considering the dispersion of its fragments, should have been placed on top of the ossuary and fell down when it collapsed, is an evidence supporting this idea. According to its decoration, this vessel can be attributed to the Hispanic-Indigenous Period (ca. 1536-1595 AD).

Pucara de Tilcara’s cemeteries

The presence of ancestors in the daily life of the Pucara’s settlers can also be perceived in the segregation of collective burial areas. This is a distinctive feature of the site, only shared with another important settlement occupied during late pre- Hispanic times in Quebrada de Humahuaca: Pucara de Volcán. In the case of Pucara de Tilcara, these areas (Figure 5), described as East, West and South cemeteries are found next to the main access roads to the site and to some housing sectors. The location of these cemeteries evidence that a numerous set of structures, daily occupied for the development of artisanal and ritual activities were spatially framed by the presence of the deaths. Beyond their inclusion within domestic spaces, the existence of these collective burial areas indicates an intention of signaling the perimeter of the Pucara with the ancestors.

Pucara de Tilcara is one of those sites that cannot be defined as pucaras in a strict sense, which is to say in the way of a fortress [55]. Although this site presents some features that could be defined as defensive, such as its location over an elevated geoform that provided a broad view of the surroundings, this could also respond to a supernatural reason, considering that the hills were identified as the dwelling site of the ancestors [56]. In this sense, the construction of over 130 graves in different foothills of this site and alongside the main access roads, in some cases occupied by 18 individuals or more [57], perhaps could be manifesting the use of landscape traits linked to the necessity of projecting a sense of pertinence and collective memory [58]. In turn, delimiting the settlement perimeter through the presence of the deceased could express that the cult to the ancestors was, among other aspects, linked to the search for protection of its inhabitants.

Discussion

In spite the variety of funerary practices from Inca moments registered both in Esquina de Huajra and Pucara de Tilcara, it is possible to point out some common elements that would allow us to characterize mortuary practices during Inca times in Quebrada de Humahuaca. Among them, we must highlight the presence of graves with positive traits that in some cases constituted true burial chambers that could be considered as “monuments to the ancestors” (as Grave 1 in Housing Unit 1 from the Pucara de Tilcara and Graves 2 and 3 from Esquina de Huajra). Although the characteristic pre-Inca funerary pattern of Quebrada de Humahuaca points to graves located below the occupational floor of the houses [59], there are some cases where raised tombs similar to the ones mentioned before were found, such is the case of Complex A of Los Amarillos site. This situation would be directly linked with the communal cult to the ancestors [35].

By adding the presence of ossuaries in both sites (Grave 1 from Tilcara and Graves 1 and 2 from Huajra), the evidences of periodic extraction of the remains or possible re-burials, and the geographic closeness of burials to settlement spaces, it is possible to argue that burials in Esquina de Huajra and Pucara de Tilcara refer to a marked tradition linked to the cult to the ancestors and that this can surely be traced back to pre-Inca times. As it has been defined for other Andean cases, these manifestations related to the veneration of the deceased could have been seeking the regeneration of crops and productive cycles in general, at the same time that ancestors could benefit the community since they possessed part of the fertility’s control (Arnold and Hastorf 2008). Therefore, the analyzed graves would allow a continued access to the remains of those people considered important (Gluckman 1937, cited in Morris 1991), whether for the social group as in the case of Huajra or for the reproduction of a family group as in Housing Unit 1 in the Pucara de Tilcara. Independently of the hierarchy of the deceased, given that we know that not every predecessor was considered an ancestor (Kaulicke 2001), we observed a frequent manipulation of the remains for the separation of skeletal parts, their re-location and even their shaping, in contexts both domestic as supra-familiar.

In the case of Esquina de Huajra, we consider that Terrace 3 would have established as a public space where several rites linked to the cult to the ancestors could have occurred. This high visibility space would have functioned as a scenario where a group of people congregated in the reduced space external to the graves (approximately 50 m2) could have conducted the corresponding rituals, being observed by the other settlers. The fact that Grave 1 and 2 were constructed over the occupational floor points to their visual impact from different sectors, especially from the North. On the other hand, the absence of covered graves would allow a continuous access to the remains of the deaths, reinforcing the character of these burials as “monuments to the ancestors” who were regularly called upon to “give food and drink to the deceased” [35].

Meanwhile, in Pucara de Tilcara we are faced with the redeposit of remains that possibly involved the development of ritual practices at an intra-domestic level. Nevertheless, given that the burial chamber was located in the large central patio, these practices should have been visualized from several points in the foothills. Perhaps, these celebrations came to exceed the limits imposed by the domestic and private plane, therefore remarking with each commemoration a kinship line and the coexistence of the deceased with the other settlers of the site. Regarding the cemeteries of Pucara de Tilcara, segregated areas from the housing units used specifically for the burial of the deceased, it is relevant their presence in the limits of the settlement and linked to the main access roads. In this sense, cemeteries could have reinforced the protection of the ancestors over Pucara de Tilcara’s inhabitants, being constantly visualized. This spatial configuration, embedded by the symbolic and the ritual, highlighted the multiple composition of the functional character of this settlement as an administrative, politic and religious center. In Esquina de Huajra, we have not found cemeteries of this type, allowing us to think that perhaps their presence in Pucara de Tilcara could be related with its functionality as capital of the province during Inca times. On the other hand, the presence of cemeteries may indicate the need to place the bodies of the deceased in segregated areas, due to the fact that many housing spaces would continue to be used. Considering the population density that Pucara de Tilcara had during the Inca Period, concentrating a large population destined to artisanal production, it is possible to estimate that the settlement would require to occupy every house and patio on artisanal tasks.

Another common trait to both settlements is the presence of direct burials exclusively dedicated to adult women (Grave 5 from Pucara de Tilcara and Grave 3 from Esquina de Huajra). The inhumation of these women, elderly for their time (over 30 years old approximately), could indicate the role they played within Inca social structure. In the case of the woman found in Pucara de Tilcara, her individualization from the whole of society could refer to the ritualization of her tasks and artisanal activities with the intention of exalting those values associated with the fulfillment of the chores [60]. Likewise, probably in both burials people sought to highlight their power as life generators, following certain principles of the Andean mythology in which the role of women and feminine deities, linked to the procurement of sustenance necessary for human reproduction, is raised [61]. The associated grave goods of both women tend to highlight their identity features. In the case of Tilcara, her figure as artisan is manifested, while in Huajra the objects refer more to her provenance, probably from the Puna.

These distinctive features were also registered in the other burials. In Esquina de Huajra, the elements included as offering specifically refer to links to other environments, as the highlands, while in Tilcara they seemed to reflect the kind of artisanal activities developed. As we mentioned before, these differences possibly responded to the sites’ functionality. Nevertheless, it is interesting to highlight that this is only expressed in the grave goods corresponding to sub-adults and adults’ individuals. The burial of children and infants in urns are frequent in both settlements. In these cases, we observe the re-utilization of ceramic pieces whose primary function was food processing, an action demonstrating that these pieces were not manufactured specifically for the inhumation of short aged children. The absence of objects destined to function as mortuary offerings for these children in the case of Pucara de Tilcara could point out that they were not considered subjects with a constituted social figure as in the case of young and adults. Their placement inside urns buried below the surface level of residential floors perhaps add to this condition, given that in a certain way they remained invisibilized, in opposition to the apparent exposition of those individuals placed in positive traits.

These multiple ways of treating the deceased and, above all, the periodic contact with their remains, demonstrate that in Quebrada de Humahuaca, as in other Andean regions under Inca domination, the cult to the ancestors kept playing an important role for the reinforcement of local identities, in certain contexts with clear hints of “Incaization”. This refers, in a case, to intentionally demonstrating the active role of artisans within the state structure, and in the other, to express the provenance of certain individuals, maybe as a reflex of the displacements of dominated populations. On the other hand, the meaning given to death is exposed once again. Contrary to an occidental point of view, where death is presented in opposition to life, mortuary practices registered here manifest the way in which the power of past generations conditioned daily life. In this sense, the deceased were presented as materially close and participants of daily decisions. This coexistence and continuity in the cult to the ancestors was possibly the one that laid the foundations for a resistance of regional identities, extremely accentuated before the Spaniard’s arrival. The mortuary contexts in Huajra and Pucara de Tilcara could be a sample of this resistance, with datings ascribable to the Hispanic-Indigenous Period [62,63]. Practices destined to maintaining this cult probably revealed that “what was to be done, was done” with the hope of ensuring prosperity and fertility. During the decline of the Empire and even more in a region distant from the capital, local societies had to reformulate their idiosyncrasy, putting into play the collective memory and slowing down the incaization process.

Acknowledgement

To the technical staff and researchers of the Instituto Interdisciplinario Tilcara, Lic. Pablo Ochoa, Daniel Aramayo, Armando Mendoza, and Presentación Aramayo, who collaborated with the digging tasks on Pucara de Tilcara. To Myriam Tarragó, María Asunción Bordach and Osvaldo Mendoça for the information provided on their research in Housing Unit 1. Also to the Tumbaya Aboriginal Community for their support to the research. The research was founded by the following projects: PICT 2015-2164, PICT 0538, CONICET- PIP 0060, PAITI Res (D) 2271.