Free List Analytics: An Overview

Michael C Robbins1* and Justin M Nolan2

1Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, University of Missouri, USA

2Department of Anthropology, University of Arkansas, USA

Submission: March 12, 2019; Published: March 25, 2019

*Corresponding author: Michael C Robbins, Professor Emeritus of Anthropology, University of Missouri, UMC, Columbia MO, 65211, USA

How to cite this article: Robbins MC, Nolan MJ. Free List Analytics: An Overview. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2019; 8(3): 555739. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2019.08.555739

What is a Free List?

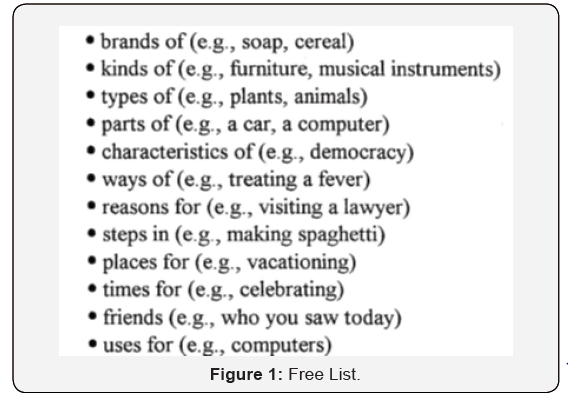

A free-list is a non-repetitive, ordered sequence of items elicited in response to imperative probes and prompts like: “List (or Name) all the… {insert domain} … you can” (Figure 1).

Free lists are especially helpful in trying to resolve the enduring ethnographic problem of discovering and eliciting what is subjectively meaningful to local respondents, but often unapparent to the ethnographer or investigator. Indeed, the use of free listing tasks to derive cognitive and ethnosemantic data from various lexically indexed, cultural domains has long been reported [1,2].

Role in Cultural Domain Analysis

Normally, as investigators we can rather easily learn what is in the mind of others that is also in our own. Usually we can find out too what is not in the minds of others that is in our own. The real challenge becomes finding out what is in the minds of respondents that is not in ours? As an example, imagine a set of 8 objects (persons, places and/ or things) {1, 2…, 8}. Let I represent the investigator’s mind and R the respondent’s mind where I = {1,2,3,4,5), and R = {4,5,6,7,8}. Notice that objects 4 and 5 are in the minds of both. Also notice that objects 1, 2, and 3 are only in the Investigator’s mind, not in the respondents [3]. And note especially that objects 6, 7, and 8 are in the respondent’s mind and not in the investigators. This is the focus of concern. How can we learn what is in the mind of others when it is not in ours? Allow us to use this set for another, more concrete, practical example. Suppose we wish to determine the brands of wine people like. We make up a list of 5 popular brands and proceed to survey the preferences of a sample of respondents [4]. Our results reveal that they like Brands: 4 and 5 and that they don’t like Brands: 1, 2, and 3; so far, so good. But what our survey results don’t reveal is that they also prefer Brands: 6, 7, and 8. More formally: How can we learn about the set difference (R-I), or that part of R, that does not intersect with I? One answer is to use free lists and free list analytics. In the example above, a respondent’s simple free listing, of all the wines preferred, yields the necessary information!

What Kinds are There?

Finite domains contain an exact, or fixed number of items. Days of the week, a normal adult body’s 206 bones, 45 United States presidents, 26 English alphabet letters or 15 basic American-English kin- terms are examples [5,6]. Infinite domains are all others, like: ‘the parts of the body’, ‘things people like least or most about their jobs’, ‘all the colors you can name’ or ‘all the medicinal plants you can think of’. In fact, free lists from finite domains appear to more closely resemble ‘free-recall’ lists about which respondents can be expected to have had prior exposure and knowledge. From a practical standpoint, free-recall of the nature and content of advertisements might be a

What Can They Tell us?

Five general types of information can be derived from free lists and their analytics. After mentioning each one we will carry on with the marketing example of brands (or types) of wine. Assuming a sample of respondents has provided free lists of ‘all the wines they can think of’, we can learn about the following:

a. Individual familiarity and knowledge of a domain which can be indicated by list length and content (4). In the wine brand problem this might equate to the number and kinds of brands mentioned.

b. Implicit groupings or sub-categorization of domain items which can be indicated by clustering (3). This equates to the degree of clustering or adjacency of various wine types. For example we might ask: do people think categorically more in terms of color like ‘reds’, ‘whites’, ‘roses’, etc.? Or, by grower/producer, grape types, and so on. How closely clustered are various competitors? Do closely clustered competitors, as indicated by item occurrence in free lists, correspond to actual market share competitors?

c. The relative salience or prominence of items in a domain which can be indicated by item list-order. More salient items are those mentioned earlier or on or near the top of the list (1, 2&4). Which wines are mentioned earlier in the list? Does this reflect preference? Advertising-induced awareness?

d. Collective familiarity, knowledge and salience of a domain which can be indicated by list item-frequency (4). Does group knowledge correspond with popularity, actual sales, or advertising?

e. Sub-sets and variations of respondent familiarity, knowledge and organization of a domain as indicated by the degree of respondents’ list-content similarities and differences (5). How similar or diverse are various domains? Do ‘experts’ differ from ‘novices’ in the content and quantity of organization or sharing of listed items in domains? How much cognitive consensus, or sharing and diversity is there when it comes to wines of various kinds?

These measures can, of course, in turn be related to personal demographics in order to more specifically target particular proper subsets of a population (Age, gender, ethnicity, region/ locale, educational status, occupation, S.E.S., etc.). It is also important to know that sequential free-listing can be done. For example, pursuant to collecting lists of wines, we could next ask: “What are all the reasons you like these wines the best?” In some of our publications it will be recognized too that after single items are listed, categories or groups of items, can as a whole, be measured for various properties such as salience, clustering, etc. Thus, the salience of reds can, for instance, be contrasted with others. In other words, both single items and categories or groups of items where n>1 can be analyzed (1, 2 & 3).