Visual Anthropology and Preservation of the Community Cultural Heritage

Sumahan Bandyopadhyay*

Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Vidyasagar University, India

Submission: October 13, 2018; Published: October 29, 2018

*Corresponding author: Sumahan Bandyopadhyay, Assistant Professor, Department of Anthropology, Vidyasagar University, West Bengal; India

How to cite this article: Bandyopadhyay S. Visual Anthropology and Preservation of the Community Cultural Heritage. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2018; 7(1): 555704. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.07.555704

Abstract

Visuals have an important place in anthropology so far as the materials and methods are concerned. Much before the formal emergence of the sub-discipline of Visual Anthropology, the anthropological engagement with visuals started. Visual Anthropology though primarily built upon the photographs - still and movies -circumscribes the entire visual system of the people. Visual aids were mainly used by the anthropologists to substantiate their data. With the emergence of visual anthropology, the visuals stood as objects of study. Now, the visuals were transformed from mere aid of documentation to a wholesome system of culture of a people. Following this transformation, the paper argues how visual anthropology can be employed in the preservation of community cultural heritage apart from substantiating and facilitating the analysis of culture. The paper also demonstrates this use of visual anthropology with illustrations from Micronesia and India. Individual scholars as well as agencies like Anthropological Survey of India have been shown as the case studies. It has also been attempted to show that the conventional technique of using photography in fieldwork is reflection of the theoretical orientations of the discipline. The paper has further tried to reveal how the use of photographic tools can be fruitfully connected to the preservation of community cultural heritage when informed through visual anthropological understanding.

Keywords: Visual; Visual Anthropology; Preservation; Community Cultural Heritage

Abbreviations: VA: Visual Anthropology; CCH: Community Cultural Heritage; SRFTI: Satyajit Roy Film Training Institute; AnSI : Anthropological Survey to India

Introduction

Anthropology is characterized by visual engagement since the very beginning of the discipline however not in the perceptible term that we now use for the sub-discipline of visual anthropology. It is a methodological indispensability in anthropology to engage with visuals as the discipline has a strong belief in Kantian metaphysical tradition based on empiric-rationalistic epistemology. However, these were mere locations or sites for observation instigated by the popular anthropological method of participant observation. But much before Malinowski’s excellent use of photographs in his celebrated Argonauts of the Western Pacific [1], utility of photographs in visually documenting the life and culture of the people was well conceived by the people among whom we find both anthropologists and non-anthropologists. In true sense, the ethnographic documentation through film is as old as cinema itself [2]. In 1895, Lumiere brothers - Auguste Marie Louis Nicolas Lumière and Louis Jean Lumière - screened their first film at Salon Indian du Grand Café in Paris. In the same year another gentleman Felix-Louis Renault filmed the pottery making skill of Wolof women and published a paper based on this record. It might have been taken as a mere coincidence if not Renault had stated in clear terms the value of his work that had differentiated it from that of Lumières’. For him, it was not a commercial utility only, rather camera should be considered as a laboratory instrument that fixes the transient human activities in perennial form amenable to further analysis. Moreover, he predicted that ethnography would attain the precision of a science only using such instruments. Visual anthropology in traditional meaning mainly deals with the still photographs and video. Sahay [3] the doyen of visual anthropology (VA)in India defines the sub- discipline in following words: Visual anthropology i inextricably connected with photography, whether it is still- photographs or films on the life and culture of peoples, that are used for teaching, research, feedback or other applied purposes. According to Safizadeh [4] Visual Anthropology is visual and perceptual study of culture, material culture, and forms of human behavior in different communities and environments. For Wacowich [5] the visual anthropology circumscribes a broader perspective. She defines it as the following.

Visual Anthropology is concerned with visual systems and forms and their engagement in process of anthropological knowledge production. Banks & Morphy [6] have commented that there is a duality of focus in visual anthropology. On the one hand, it is concerned with the use of visual materials for anthropological research, on the other hand, it is the study of visual systems and visible culture. According to them there are two overarching agenda of visual anthropology. One agenda is to analyze the properties of visual systems, to determine the properties of visual system and the conditions of their interpretation, and to relate the system to the complexities of social and political processes of which they are parts. The second agenda is to analyze the visual means of disseminating anthropological knowledge itself. They have tossed with the idea whether it can be taken as a method or a theory and came to the opinion that a complete divorce between theory and method is not possible, however they admit that the dimensions have different ontological statuses. From various discussions the features of this sub-discipline appear to be the following:

a. The analysis and formation or structuring of reality as reflected through visual productions and artifacts.

b. The cross-cultural study of this visual productions from social, cultural, historical, and aesthetic points of view.

c. The study of the relationship of cultural and visual perceptions.

d. The study of the forms of social organization surrounding the planning, production and use of visual symbolic forms.

In an international seminar on visual anthropology held in India in 1987, Roy & Jhala [7] put forward seven intermediate objectives of visual anthropology. In these objectives they mentioned that the necessary tasks ahead include:

Increasing dialogue between anthropologists and film makers mainly on the issues of ‘other’, ‘text’, politics of portrayal, social change.

a. Increasing dialogue between anthropologists and film makers mainly on the issues of ‘other’, ‘text’, politics of portrayal, social change.

b. Increasing interactions between East and West.

c. Use and telecast of visual anthropology materials in the national network by the government

d. Promote follow up workshop etc.

e. Training.

f. Dissemination of information sphere.

g. Publication.

However, another view of visual anthropology as proposed by Jacknis allows it a very broad compass of visible world Jacknis writes [8]. In many minds the term visual anthropology conjures up a specialized study involving film and video. Its scope is much broader, including the production and analysis of still photos, the study of art and material culture, and the investigation of gesture, facial expression and spatial aspects of behavior and interaction. In all these studies, we find virtually no reference to the use of visual anthropology in the act of preservation of cultural heritage. But it is undeniable that the visual anthropology carries immense potential as a tool of cultural preservation. In the present paper, I shall try to focus on this very aspect of visual anthropology. The data for the study has been the ethnographic documentaries made by anthropologists as well as non- anthropologists; the visual productions and producers i.e. thank (Tibetan scroll-painting), pata (Scroll-painting of Bengal), wall paintings, serpai (metal craft). The present author has been associated with making of documentary; moreover, he has been anthropologically exposed to the areas and topics by means of fieldwork. The studies on the folk-art forms taken as examples of visual productions in this paper have been done in Sikkim and West Bengal. The paper also utilizes a case study by anthropologist Allan Burns [9] in Micronesia that can be considered as a worthy effort in the utilization of visual anthropology in preservation of heritage.

Community Cultural Heritage

Heritage has been quintessentially a value - added idea clothed in material or non-material forms. It is the essence not the elemental reality that determines heritage [9]. Heritage is that material or non-material item of culture of a community that considers it to be an essential of that community. It is a symbolic embodiment of the culture or people concerned. The community cultural heritage is the collective cultural products of that community or productions that share the elements present in collective conscience to borrow the term from Durkheim. Barbara Kirshenblatt Gimblett [10] characterized heritage in the following way:

a. Heritage is a mode of cultural production in the present that has recourse to the past.

b. Heritage is a “value added’’ industry.

c. Heritage produces the local for the export.

d. A hallmark of heritage is the problematic relationships of its objects to its instruments.

e. A key to heritage is its virtuality, whether in presence or the absence of actualities.

The characterization is both etic as well emic in nature because about value addition and export the etic view rules the roost, but when it comes to cultural production the community itself takes the pivotal role by making it a subject of emic understanding. The early history of visual anthropology reflected predominance of etic view, but gradually the value of emic that is insiders’ understanding of the visual is getting acceptance. In a review article Deborah Poole [11] has indicated this shifting nature of visual anthropology. Here she has mentioned that the early work in visual anthropology was explicitly concerned with the countering of the notion of exploitative and racializing expropriation of the indigenous people. Therefore, the derogatory practice of ethnocentrism was disquieting stimulus against which anthropology had to set its agenda. Poole [11] however, finds that the more recent works mostly center round the theories of ethnicity and identity formation a more substantive undertaking akin to heritage preservation through community effort. An example of such effort can be presented through a study of Allan Burns that deals with visual literacy as a potent means of cultural preservation.

In the case of Community Cultural Heritage (CCH), the ownership rests with the community concerned. CCH includes both tangible and intangible heritage. When we relate visual systems to community cultural heritage, it appears that the visual productions of a community are included in this domain. The crafts produced by a community are very much a part of the CCH when the knowledge of its production is shared by the community. Apart from these, all the visuals created and shared by the members of a community constitute the CCH of the concerned group of people. The paintings on walls of Santal houses, the pata (scroll painting) by the Patua community are some examples of the CCH. Body decorations sometimes reflect the identity of a group. The tilak worn by the Vaishnava is characteristic of their belonging to a Vaishnava sect. When CCH is informed by VA, it must take into consideration this type of symbolic communication as well. We have come to know that visual anthropology, in brief, is the study of visual system. Photographs and films are very prominent examples of this visual system. But these are most often built after non-visual system like aspects of material culture, house type. These components of non-visual system are therefore routed through camera to become subjects of visual system in ethnography. There is another category of visual system, that include the paintings, inscriptions, body art etc. These are directly accessible to an observer of culture. Thus, we have two different scopes of visual anthropology.

a. Study of visual system sui generis and

b. Study of the construction of visual system.

While visual anthropology is engaged in the conservation of CCH it is concerned with both exercises. The salvage work of the conservation is related with documentation as well as the process of documentation that is in the construction of visual system.

Visual system represents the cultural heritage of a community. The characteristic artefacts or designs, architecture etc. are documented by the interested people including researcher. The photographs or videos of these type by detour become parts of the CCH – however at a secondary level. These visuals may be produced by individual member of that community or an outsider. In all the instances the visuals captured are snapshots of the community life which represents the collective identity of the group in question. Visual anthropology – though has a scope to deal with both the individual and collective sorts of visuals, is a bit biased towards the collective representation of community for the obvious reason of its characteristic disciplinary practice. In this pursuit, it not only documents the minute details of the cultural traits of a community, but also tries to understand how this visual system is maintained in that community. Thus, it is a study of product as well as process. In this way visual anthropology proves of substantial merit in a rounded study of Community Cultural Heritage.

Visual Literacy and Cultural Preservation

The skill of learning to look at an image for a long time and explore the relationship of visual content, composition, and communication is the first aspect of visual literacy [9]. The second aspect is the ability to create image. Burns [9] carried out this project in Pacific island of Micronesia. The project was directed towards two themes:

a. Cultural Preservation.

b. Cultural Resistance.

Burns [9] Cultural preservation often leads to the celebration of culture through museums, folklore performances, and demonstrations by experts in crafts of folklore. In Japan, there is a programmed to find out folk artists and to certify them. Later they are given stipend to continue their craft. Government of India also promotes endangered art and crafts by giving stipends and scholarships to expert practitioners. In West Bengal, now the folk artists are being regularly engaged in various awareness programmed by state government with financial assistance.

Burns was himself engaged in one such cultural preservation project in Micronesia. The project has an objective of nationbuilding. Besides it has three distinct elements.

a. To write and implement policies to limit the destruction of cultural ecology of the area.

b. To carry out basic research on archaeology and ethnology.

c. To promote awareness of the importance of cultural preservation.

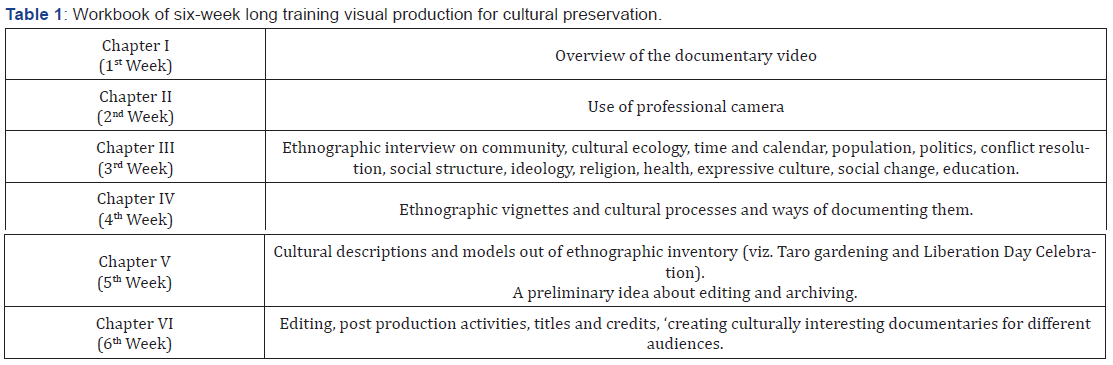

Burns organized a six week of training of the crew initially at the island of Korsae and then started field production. He took them into research at cross-cultural set up and put them into filming difficult situations. The third stage involved operating a production studio and transmission of edited programmes on island television. In this project Burns involved museums. The museum staffs were trained in ethnographic techniques and were made familiar with professional documentary techniques. Twenty episodes of Korsae life were videotaped. Of course, some professional film makers were hired. Burns made a ‘ethnographic video workbook’ for the training of the local participants. Each chapter is designed to be covered in each week (Table 1).

An Indian Example: The case of AnSI

Anthropological Survey of India, the premier anthropological research Centre of the Government of India since its very beginning realized the importance of photographic medium. It opened a cinema and photography section at the year of its establishment in 1945. It shot several films the list of which is now available in the website of the organization. The members of this unit produced a good number of films on the tribal people of India despite their limited resources. The focus of this unit was documentation of dying cultures or capturing the lives of people in events in still and motion.

With the emergence of the new field of visual anthropology the use and produce of camera went through sea changes. In this field, AnSI made some pioneering efforts. One among these was the organization of international seminars and formulation of an acceptable disciplinary (or sub-disciplinary) model to follow in case of visual anthropology. At the theoretical level these were good efforts no doubt. But while taking stock of the actual output the story is rather bleak. So, there was a need to do something of practical nature. In 2007, a definite step was taken with the opening of the ‘Centre for Visual Anthropology’. The purpose of this center was to train in-house scientific members in the art and craft of film making. It was so conceived that the knowledge of making film would induce the analytical faculties to produce synergistic result we may call visual anthropological. V.R. Rao, the then Director of AnSI inaugurated the programme in collaboration with the Satyajit Roy Film Training Institute (SRFTI). The training was residential. Around twenty-five staff members of the Survey including sound technicians, photographer, computer personnel apart from predominating number of social anthropologists and one physical anthropologist took part in the training. It was a three weeks’ programme that imparted theoretical knowledge with hands on training. The topics included: direction, light, sound, editing, mixing, writing of concept note. At the end of training four groups were formed. Each group was entrusted with the exercise of doing fieldwork within Kolkata and to make a film of ten-minute duration. The teams produced four documentaries:

a. Doms of Kolkata,

b. B+,

c. Kumartuli (on the idol makers of Kolkata)

d. Prolonged Shadow (a documentary on the aged people).

This exercise has been furthered by the approval of doing audio-visual documentation along with the projects formally written. One can make a documentary with the sanctioned projects if so proposed and approved. Following this official notification, a documentary, titled Ultra (The northern wind) was produced as a part of project on traditional knowledge of the Coastal Fishermen. Keeping this trend in motion, this unit of survey has so far produced a good number of documentary films. Of these films Ghoul was screened as a part of the UNESCO culture heritage documentation. An Incessant Voyage produced by the team portrayed the journey of Anthropological Survey of India over the period as a premier institution of anthropological research in the country. Two more films – one on the glove puppet (Beniputul) and the other on Kabigan earned acclaim of the critics. Now the survey is organizing a training programme each year for the staffs of the institution stationed at different parts of the country.

From the analysis of the effort of the survey, it appears that the main objectives of this training – cum - production are twofold. One, it is the documentation of the rich and diverse cultural heritage of India. Two, it is to explore the possibility of this new media in the furtherance of anthropological research. In both these objectives, the idea of documenting CCH is latent.

Ethnographic Film and Documentaries

From the fore going discussions on the relationship between CCH and VA, it can be surmised that films and photographs are potent tools for effective conservation of CCH. Anthropologists have made extensive use of photographs in understanding the social-cultural life of the people they study. Photographs have multiple use for the ethnographers ranging from collection of data to their representation [12-16]. The films and photographs were purposively used by Bateson & Mead [12] to present an ethnographic study in Indonesia. They took as many as twentyfive thousand stills and twenty-two thousand feet long films on the people of Bali [17]. Their aim was theoretical as they tried to prove their point in culture and personality school, albeit it showed how extensively photographs can be used in anthropological studies. Nowadays, the use of camera is almost inevitable [16,18].

The ethnographic film has the primary aim to preserve the structure of event it is recording as interpreted by the participants, in the mind of the viewer [19]. It is imperative for an ethnographic film maker to be successful that he or she thoroughly understands the people to be filmed. It is also desirable that the indigenous structures or native categories guide the film maker. Asch [19] have mentioned about three important categories of ethnographic film -

a. Objective recording - a) descriptive b) analytical.

b. Scripted filming.

c. Reportage.

Scripted filming is mostly the form taken particularly by non-anthropologist film maker. But the most successful filming practice is the combination of the all the above-mentioned tropes in varying proportions as per the ground realities and aesthetic sensibilities demand. Of all these the reportage is probably the best means for the preservation of cultural heritage as it attempts to do a complete shoot of an event or a segment of life with adequate footage. In the present study we have chosen the example where the categories of ethnographic film as mentioned above do not appear as sharp typology.

Beniputul - Glove Puppet

This film has been made by Dr. Nabakumar Duary of Anthropological Survey of India. He has delineated a dying folk art tradition of glove puppet (beniputul) of Bengal. It was shoot at a village named Padmatamali of Purba Medinipur district of West Bengal. The storyline mainly focuses on the changing occupational profile of the people, change in the craft itself, the way of showing this performance, the caste background, craft work of making beniputul and the hardship of their life. The film maker has shown that now only four families depend on this craft for their livelihood, whereas some fifty years back about eighty families were engaged in it. In a review of this film, another veteran anthropologist Professor Ajit K Danda [20] writes being under pressure of changing times, it is only natural that the Beniputul, originally made of bamboo-splits, gets wooden limbs and the dry palm-seed head of it, through phases, gets replaced by terracotta models.

The ethnographic film used multiple tropes to vivify the mundane life of the glove puppet players. It was based on both objective recording as well as scripted filming. The original interviews in vernacular were shown with English subtitles. The film conveyed us the details of the ecological setting, aspects of rural life in Bengal, the making of Beniputul, tactics of playing the puppets, their actual playing with songs in the market place, the audience. The changing aspects of the life of puppet players had been emphasized. The narrative was substantiated by moving pictures. But, in its own language, the film would add something new that could not lie only in description or photography. For this film, the unique suggestive moment was created. Danda wrote:

Obviously the ever-busy red ants must be on the rush in search of a greener pasture and the relatively slow-moving mother duck would, instead, prefer to operate within a limit remaining tied up to the tradition [20].

The film contributed to the documentation and preservation of CCH. The fading art of glove puppet was preserved in documentation for the posterity. The anthropologists worked with the community members for getting a ‘field-view’ of the craft in practice. Thus, the knowledge of the community members was preserved in this way. But, at the same time we find an interpretation which was visual anthropological.

Uses of Photographs: An auto-ethnography

As an undergraduate student, I was asked to take photographs to substantiate the field report. With an analogue ‘Hotshot’ camera I took about twenty photos on the different aspects of the life and culture of the Santal people living at Baghashola village in Dumka district of earstwhile Bihar state (now Jharkhand). I had no instruction what to shot. Only what we know was to take some photographs that would adequately reflect the culture of the people living there. On the basis of my understanding of the topics given in the syllabus , I took photographs of landscapes, panoramic view of the village, village entrance, , linear pattern of arrangement of houses along the road that bisected the village, house type, agricultural implements, agricultural activity of threshing that was going on there at that time besides pictures of majhithan (seat of the village headman) , jaherthan ( the sacred grove). Moreover, I took another photo of myself taking interview of an old Santal inhabitant of the village. We also took a group photo of ourselves with the departmental banner spread before us. This has been a guideline followed till today at the initial stage of field training that I am to impart my graduate students.

In later years of my student life, when I came to reason more with the utility of photographs in ethnographic reports, I find how naïve I was in accounting the right value to the photographs. I know it very well that photographs cannot show everything, but some more things that it could have shown I missed during my early years of apprenticeship. I found the Santals with tattoos on their body. What did they mean? What were the designs? How it varied? How it was done? on which part it was done? These are the some of the so many things I did not consider photographically at that time. We were offered hanria, intoxicating drink fermented from rice at home and almost all of us accepted this. Under the influence of this hard drink our behavior changed, so theirs. We did not catch this evidence of rapport and reflexivity. Even some of us took photos of that inebriated state but did not have courage to paste those photos in the report. It is not camera, again it is the culture, because we fear that these photographs might tarnish our image. Another reason might be that we operated within a preconceived scientific frame that did not allow the depiction of such personal emotional and way ward state.

Taking of photographs owes its origin in the tenets of positivism and empiricism that cast an overarching influence on the methods of collection of data in anthropology. Positivist and empiricist approaches lay stress on observation. Photography is the freezing of an observed moment. At the initial stage, I was mainly impressed by the material details that photographs could capture comparatively well. Photographs proves that ‘I was there’ - this sense of ‘being there’ is one of the core features of positivism. This way photographs establish a ‘positive’ kind of authority of the field worker. When I came to realize the meaning of authority and its appropriation through photographs, I must say that I have learnt something beyond the simple material use of photography.

Jorgensen [16] has rightly remarked that ‘the camera is an extension of visual perception’. Photographs reflect the culture of the user. Taking of photographs is very much influenced by the topic of investigation as well as the social location of an individual researcher. The general feeling is to take photo of what appears to be different or ‘exotic’. Thus, camera starts a process of ‘othering’, considered to be a hallmark of understanding anthropological process. This ‘othering’ starts from tangible world, from material culture to social events. For a general ethnographic account, as I find and follow, the photographs include mundane aspects of life – landscape, house type, dress pattern, ornaments, utensils, implements, musical instruments, designs, pieces of arts and crafts etc. The human figures are often presented of particularly in the older monographs. This is done mainly from a view of giving a sense of the physical environment - the ‘context’ of the study. The comparative method is embedded in this exercise. Thus a ‘textualization’ of context takes place. By this the community cultural heritage is not only documented but contextualized in a ‘textual’ format.

The next step is to take photographs of ‘human in action’. In doing so more we become familiar with the social organization of the people we study; our photographs turn to be more focused and speaking. Now we try to capture the essential and characteristic features of the community. In my fieldwork among the Santals, I concentrated on the festivals and cultural performances of the Santals. I brought my camera to take photographs of the festive dances, rituals observed at the time of festivals, the places of worship and performances at jaherthan, and akhara, the decorations on their house and the instruments they were playing. The photographs depict well the scene of dance and other performances both ritualistic and non-ritualistic. The pictures portray the gender difference in performance and attires, the utilization of space and the symbols they draw on the floor, the structures they constructed on festivals. Through these photographs I could easily show how the context had visibly become different at the time of festivals. Now the comparison was within the limited universe that had become different with change of time.

From the above delineation it is quite clear that the context is being determined by the text and this can well be shown using photographs. I tried to focus on the features of dance patterns which appear very different from the ones we are familiar with as non - Santal. In this regard it can be said that certain material objects qualify to be portrayed better in photos than described. In the present case, I added the photographs of bhuang in the report. The instrument of bhang is played at the time of Dashain festival when the Santal men dance dressing like women. The instrument is made by them from hollow gourd attached to a string which is kept in tension by the bent strip of bamboo that is also fitted with the body of the gourd. I can easily understand that this description is still falling short of the actual instrument captured in the photographs. Another such instrument is sarpa played by the women while dancing at the time of sohrai festival of the Santal.

Outside the immediate periphery of issues of academic notice, the camera serves some other purposes that bear significant moorings in anthropological fieldwork. Camera helps to build up a good rapport with the people in the field. Initially, the fieldworker moving in the field area with the camera slinging from his or her attracts attention for being different from the people who usually visit the area. I was very often asked by the people whether I was a reporter from any newspaper. In replying and clarifying my cause of moving so, I got an initial entry into the locale at many times apart from a guided introduction by some influential persons of the locality. In most cases people liked to be photographed. The digital camera now provides us with enormous facility to take many photographs and to show the people what I have shot in the field. It is sometimes shown immediately after the shot, or they can browse the photographs I have taken of them. I very often allow them to browse the photos and expect their comment.

I have found that this exercise has several implications. First, by allowing an insider to this exercise I acknowledge the proprietorship of the person over the corpus of cultural material I have amassed of them. Secondly, while scrutinizing the photographs he or she might see whether I had breached or disregarded anything like a cultural taboo in their society or whether I had gone some way beyond the limits of decency. Thus, this act of scrutiny was a kind of acceptance by the people if so checked, commented and allowed. Thirdly, if I need any clarification I might inquire for the further details. Fourthly, from their comments some new points might emerge. So, apart from being a tool of simple collection of data, the camera was linked with many other facets of inquiry.

As I have mentioned earlier that camera helps to foster a good rapport between insiders of a community and the fieldworker doing research on them. I showed two of my informants how to take snaps. Both were mostly inclined to take photographs of their own relatives and friends. This is interesting in the sense that the things or phenomena which are of much importance to me are no more points of attraction for them. Therefore, the commonsense ‘othering’ is a vice-versa process, unless guided one cannot take photographs which are mutually significant or characterized by inter-subjective values.

Conclusion

The present paper discusses the role of visual anthropology in the preservation of community cultural heritage. It has dealt with the idea of visual anthropology and how it has emerged to include the entire visual system in the ambit of study. The community cultural heritage, the collective cultural product of the community includes both the tangible and intangible aspects of culture. The visual anthropology can be used to enhance the visual literacy of the community members as has been illustrated through the Micronesian case study. Besides this individual effort, the government agencies like Anthropological Survey of India (AnSI) plays significant role in the preservation of CCH.

The AnSI has made several such films on the community cultural heritage one of which has been taken here as an example. The film made on glove puppet (Beniputul) shows how this folk craft tradition is in vogue in rural Bengal and its dwindling condition. However, it has still preserved much of this traditional craft beyond mere documentation. The paper has showed the visual anthropological input into this work of ethnographic film which has become a means of preserving CCH. The autoethnographic account presented here manifolds how the use of ‘photographic method’ in fieldwork as an apprentice and later a professional of could go beyond the mere supporting documents to field report to an account of community cultural heritage. The photography in anthropological fieldwork can be linked positivistic and empiricist tradition in anthropological research. But, this very aid to ethnographic fieldwork has great implication for visual anthropology since the issues like ‘textualization’, ‘othering’, ‘intersubjectivity’ can be meaningfully shaped through this practice as has been demonstrated here. The photographic instrument acts as a tool in establishing rapport with the community members. The outcomes of the visual exercise can be placed before the scrutiny by the community members whose participation thus enhances the utility of visuals in CCH.

References

- Malinowski B (2002) Argonauts of the Western Pacific. Routledge. London, UK.

- Bandyopadhyay Sumahan (2014) Rain on the Mirror. The Indian Journal of Anthropology (1): 79-82

- Sahay KN (1993) Visual Anthropology in India and its Development. Gyan Publishing House. New Delhi, India.

- Safizadeh Fereydoun (1997) Visual Anthropology. In: The Dictionary of Anthropology. Thomas Barfield (Eds.), Blackwell Publishers. Oxford, UK.

- Wacowich Nancy (2010) Visual Anthropology. In: The Routledge Encyclopedia of Social and Cultural Anthropology Alan Barnard Jonathan Spencer (Eds.), Routledge. London, UK.

- Banks Marcus, Howard Morphy (1999) Rethinking Visual Anthropology. Yale University Press. New Haven, USA.

- Roy Rakhi, Jayasinhji Jhala (1992) An Examination of the Need and Potential for Visual Anthropology in the Indian Social Context. In: Visual Anthropology and India. Singh KS (Eds.), Anthropological Survey of India. Calcutta, India.

- Jacknis Ira (1994) Society for Visual Anthropology. Anthropology Newsletter 35(4): 33-34

- Burns, Allan (2008) Visual Literacy through Cultural Preservation and Cultural Resistance: Indigenous Video in Micronesia. Journal of Film and Video 60(2): 15-25.

- Kirshenblatt Gimblett Barbara (1995) Theorizing Heritage. Ethnomusicology 39(3): 367-380.

- Poole Deborah (2005) An Excess of Description: Ethnography, Race, and Visual Technologies Annual Review of Anthropology 34: 159-179.

- Bateson G, Mead M (1942) Balinese Character. Academy of Sciences. New York, USA.

- Collier J (1967) Visual Anthropology. Holt, Rinehart & Winston. New York, USA.

- Hocking P (1975) Principles of Visual Anthropology. Mouton. The Hague, The Netherlands.

- Becker HS (1981) Exploring Society Photographically. University of Chicago Press. Chicago, USA.

- Jorgensen Danny L (1989) Participant Observation- A Methodology for Human Studies. Newbury Park. London, UK.

- Jacknis Ira (1988) Margaret Mead and Gregory Bateson in Bali: Their Use of Photography and Film. Cultural Anthropology 3(2): 160-177.

- Fetterman David M (2010) Ethnography Step-by-Step. Sage. Los Angeles, USA.

- Asch T (1973) Ethnographic Film: Structure and Function. Ann Rev of Anth 2: 179-187.

- Danda Ajit K (2013) Beniputul: An Ethnographic Documentary. The Indian Journal of Anthropology 1(1):147-152.