Metal Weapons of “Warrior’ Burials” Found in the Middle Bronze Age II Southern Levant – Economical and Social Aspects

Tal Kan Cipor Meron

The Leon Recanati Institute for Marine Sciences and Zinman Institute of Archaeology, The University of Haifa, Israel

Submission: August 06, 2018; Published: August 16, 2018

*Corresponding author: Sariel Shalev, University of Haifa, Address: 199 Aba Khoushy Ave., Mount Carmel, Haifa, Israel; Tel: 972-547682053; Email: masabazman@walla.co.il

How to cite this article: Tal Kan Cipor Meron. Metal Weapons of “Warrior’ Burials” Found in the Middle Bronze Age II Southern Levant – Economical and Social Aspects. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2018; 6(1): 555676. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.06.555676

Abstract

Copper-based weapons including battleaxes, daggers, and spearheads from the Middle Bronze Age II (c. 1900-1600 B.C.E.) have been unearthed mainly in burials found in the southern Levant. Archaeological and metallurgical analyses of these metal weapons done recently, make it clear that in the beginning of the period, in the decorated weapons were made of tin bronze with and without arsenic while during the second part of this period we can see a decrease in the number of weapons found in graves as well as changes in the metallurgical composition into the usage of tin bronze, arsenic copper and copper with tin and arsenic. To explain these results, there is a need to look further on the possible social economical context of the “Warrior’ burials” phenomenon using metal weapons made of copper, arsenic, and tin, which are unavailable metals in the southern Levant at this period.

Keywords: Metal Weapons; Warrior Burials; Middle Bronze Age; Tin Bronze, Arsenic copper; Southern Levant; Kit; Tin; Archaeological; Funerary contexts; Society; Copper sources

Case Report and Results

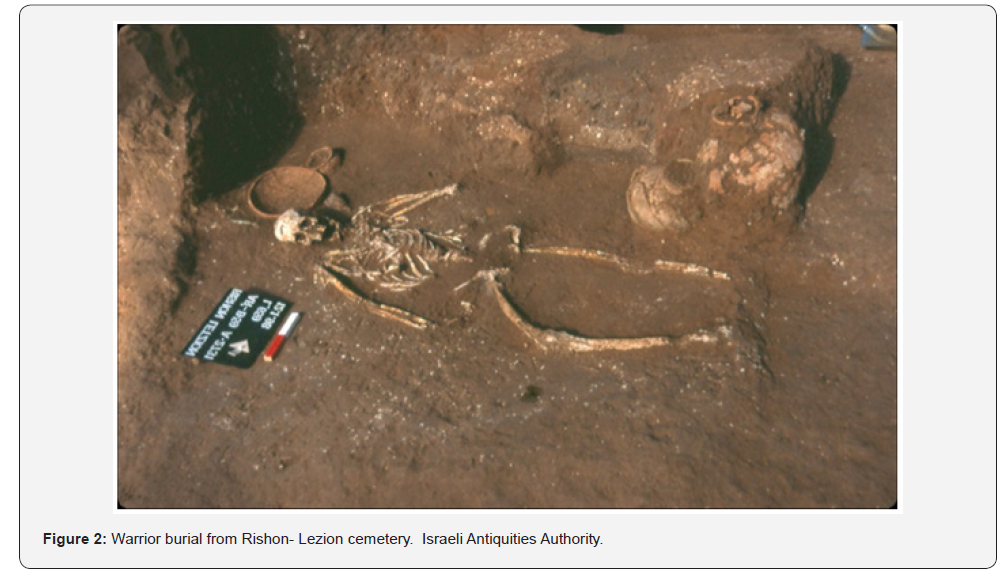

More than 1000 copper-based weapons associated with the Middle Bronze Age II (MB II; ca. 1950–1550 BCE) culture have been recovered, primarily in burials, throughout the Levant (Figure 1); [1-7]. These, funerary contexts have generally been referred to as “warrior burials”, and contained individuals buried with a presumed “kit”, comprising weapons, such as daggers, axes and spearheads found on the deceased’s waist and/or next to their head (Figure 2). The “warrior burials” are dated mainly to the first half of the MBII period (MB IIA; 1950–1750 BCE) and decline in occurrence in the Middle Bronze IIB (MB IIB; 1750–1550 BCE) [6-8].

Recently, it has been shown [6,7] that less than 25% of all the MB IIA burials can be defined as “warrior burials”, and they should rather be considered to reflect high-ranking members of the contemporary society, i.e., an elite social class . The weapons in the MB IIA “warrior’ burials” were well-made, elaborate and composed of copper alloyed with up to 14% tin, both with and without low arsenic concentration [5-7].

The use of tin bronzes is considered the most important technological innovation of the Middle Bronze Age II (MBII). Tin Bronze objects are known from earlier periods, but in small quantities while the use of arsenic copper was more common [5,9]. During the Middle Bronze Age II, tin bronze was widely used to create metal objects in general and weapons [5,6,7,10]. While for production of arsenic copper one metal source containing copper with arsenic was needed, the production of tin bronze required two metal sources, one of tin and one of copper, which were in far distance from the southern Levant [11,12]. Nevertheless, no tin sources were found in the Levant and there is no evidence that local copper sources were exploited at this time, in contrast to the former periods [13-15]. In addition, almost no ingots and complete workshops from this period were found in the Levant [1,2,14-16]. This raise a series of significant questions concerning the factors that led to the widespread use of tin bronzes at this period, the sources of copper and tin, and the trading systems that brought the raw materials and the finished products to the Levant.

In addition, to date, the transition from the use of arsenical copper to tin bronze was perceived as a linear development; It was assumed that at the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age (MBIIA), most weapons, in continuation of the former period, were made of arsenical copper, while in the later part of the period (MBIIB), most of the weapons were made of tin bronze [5]. Through a detailed analysis of the available metallurgical data we have shown that the situation was in fact quite the opposite. It was demonstrated that the transition was highly complex; Tin bronze appeared quite abruptly in the MBIIA, with only few antecedents, and decreased during the MBIIB [6,7].

Discussion

Therefore, gradual linear development cannot explain this transition, but rather social circumstances that are to the MBIIA as well as developments in the wider region, including the development of trade networks that enabled the transport of the necessary raw materials – copper and tin. Trade routes that connected Mesopotamia with Anatolia as well as the Levant in the early second millennium are known from both texts and archaeological evidence. The Mari and Kultepe-Kanish archives dated to the MBIIA support this picture of long-distance trade connections and provide some information on the metal supply system during this period, mainly of copper and tin [12,17]. Through these trade routes, the social concepts of the “Warrior’ burials” could penetrate the southern Levant, as burials of high rank members in the society with elevated status. In the MBIIB, with the increased Asiatic presence in the eastern part of the Egyptian Delta, trade contacts with Anatolia decreased [18-22].

Thus, these extensive political and socio-economic changes in the MBII period may explain the change in availability of raw materials and metal products and should be further explored.

References

- Philip G (1989) Metal Weapons of the Early and Middle Bronze Ages in Syria- Palestine. BAR International Series no. 526 (I&II), Oxford, UK.

- Phillip G (2006) Tell El-Dab’a XV: Metalwork and Metalworking Evidence of the Late Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period. Vienna: Verlag der Österreichischen Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Miron E (1992) Axes and Adzes from Canaan. Prähistorische bronzefunde. Franz Steiner, Stutgart, Germany.

- Shalev S (2008) Southern Levant, Bronze Age Metal Production and Utilization. In: Praesall SM (Eds.), Elsevier Encyclopedia of Archaeology. Academic Press, New York, USA, 1: 898- 899.

- Shalev S (2009 Metals and Society: Production and Distribution of Metal Weapons in the Levant during the Middle Bronze Age II. In: Rosen SA, Roux V (Eds.), Techniques and People. De Boccard, Paris, France, pp. 69-80.

- Kan-Cipor-Meron T (2017) Metal Weapons of Middle Bronze Age II in the Eastern Basin of the Mediterranean Sea – Economical and Social Aspects. (Hebrew). Unpublished PhD thesis, The University of Haifa, Haifa, Israel.

- Kan-Cipor - Meron, Shilstein S, Levi Y, Shalev S (2017) A Comparison Study of Middle Bronze Age II Daggers and their Rivets as Tools for Better Understanding Their Production. Archaeometry p. 1-19

- Burke AA (2014) Introduction to the Levant During the Middle Bronze Age. In: Steiner ML, Killebrew AE (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant, c. 8000-332 BCE. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 403-413.

- Garfinkel Y (2001) Warrior Burial Customs in the Levant during the Early Second Millennium BC. In: Wolff SR (Eds.), Studies in the Archaeology of Israel and Neighboring Lands. Atlanta, Georgia: ASOR Books 5: 143-161.

- Caspi EN, Ettedgui H, Rivin O, Peilstöker M, Breitman B, et al. (2009) Neutron Diffraction of Two Fenestrated Axes from ‘Enot Shuni’ Bronze Age Cemetery. Journal of Archaeological Science 36(12): 2835-2840.

- Shalev S, Caspi EN, Shilstein S, Paradowska AM, Kockelmann W, et al. (2014) Middle Bronze Age II Battleaxes from Rishon LeZion, Israel: Archaeology and Metallurgy. Archaeometry 56(2): 279-295.

- Nezafati N, Pernicka E, Momenzadeh M (2006) Ancient Tin, Old Question & A New Answer. Antiquity 80: 308.

- Lehner JW (2014) Metal Technology, Organization, and the Evolution of Long - Distance Trade at Kultepe. In: Atici L, Kulakoglu, Barjamovic G, Fairbairn A (Eds.), Current Research at Kultepe-Kanesh. Atlanta, GA: Lockwood Press on behalf of the American School of Oriental Research. pp. 135-156.

- Levy TE, Najjar M, Ben Yosef E (2014) Conclusions. In: Levy TE, Najjar M, Ben Yosef E Smith NG (Eds.), New Insights into Iron Age Archaeology of Edom southern Jordan. The Cotsen Institute of Archaeology Press, University of California, Los Angeles, USA, pp. 977-1001

- Yahalom-Mack N, Galili E, Segal I, Eliyahu Behar A, Boaretto E, et al. (2014) New Insights into Levantine Copper Trade: Analysis of Ingots from the Bronze and Iron Ages in Israel. Journal of Archaeological Science pp. 159-177.

- Yahalom-Mack N, Gadot Y, Eliyahu-Behar A, Bechar S, Shilstein S, et al. (2014) Metalworking at Hazor: Along-Term Perspective. Oxford Journal of Archaeology 33(1): 19-45.

- El-Morr Z, Pernot M (2011) Middle Bronze Age Metallurgy in the Levant: Evidence from the Weapons of Byblos. Journal of Archaeological Science 38(10): 2613-2624.

- Bonacossi DM (2014) The Northern Levant (Syria) During the Middle Bronze Age. In: Steiner ML, Killebrew A (Eds.). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant, c. 8000-332 BCE. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 414-433

- Oren ED (1997) The Hyksos: New Historical and Archaeological Perspectives. University of Pennsylvania Museum, Philadelphia, USA.

- Ben-Tor D (2011) Egyptian - Canaanite Relations in the Middle and Late Bronze Ages as Reflectaed by Scarabs. In: Bar S, Kahn D, Shirley JJ (Eds.), Egypt, Canaan and Israel: History, Imperialism, Ideology and Literature. Boston, Leiden, Netherlands, p. 23-44.

- Burke AA (2014) Introduction to the Levant During the Middle Bronze Age. In: Steiner ML, Killebrew AE (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant, c. 8000-332 BCE. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, pp. 403-413.

- Doumet-Serhal C, Kopetzky K (2012) Sidon and Tell el-Dab‘a: Two Cities-One Story: A Highlight on Metal Artefacts from the Middle Bronze Age Graves. Archaeology and History in the Lebanon 34: 9-52.