Indispensable Knowledge of Eclampsia for Archaelogists and Anthropologists

Pierre Yves Robillard*

Department of Neonatology, University Hospital South Reunion, France

Submission: July 25, 2018; Published: July 31, 2018

*Corresponding author: Pierre Yves Robillard, Department of Neonatology, University Hospital South Reunion, BP 350, 97448 Saint-Pierre cedex, France, Tel: (262) 2 62 35 91 49; Fax: (262) 2 62 35 92 93; Email: pierre-yves.robillard@chu-reunion.fr

How to cite this article: Pierre Y R. Indispensable Knowledge of Eclampsia for Archaelogists and Anthropologists. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2018; 5(4): 555670. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.05.555670

Abstract

Witnessing a “Grand-mal” epileptic crisis is undoubtedly one of the most impressive events which may happen to any observer (including those who have chosen to work in the medical field). Convulsions have been described and written down since the beginning of writings 5,000 years ago in all continents. Specific to humans, eclampsia, which is a grand-mal epilepsy, happens naturally in 1% of all human births and is responsible of a very high rate of maternal deaths near or at delivery, with also often the death of the foetus or the newborn. Further, it happens preferentially during the first pregnancy, therefore in very young previously very healthy women. Mankind has then eternally lived with this apparent “curse” happening in its reproduction. The terror that inspires this spectacular feature, even nowadays, has undoubtedly shaped the human conscience and interpretations since the beginning of our species, moreover because it happens during the paramount emotional event which is a birth. The author wishes that (paleo) anthropologists and archaeologists integrate this datum in their reflections. For example, the upper Palaeolithic so-called “Venuses”, could be protective talismans for pregnant women not only for birthing, but also against the terrorizing convulsions (eclampsia) which could happen in all human pregnancy, especially in the first ones (primiparae).

Keywords: Eclampsia; Preeclampsia; Medical history; Anthropology; Reproduction; Venuses; Curse; Grand-mal; Plague; Inflammation; Ethnologists; Archaelogists; Human; Disease

Introduction

It is of great paradox that, besides medical scientific journals, in general science (and even in general press such as feminine magazines for example), very few is written on the plague of human reproduction which is eclampsia (and pre-eclampsia). Yet, these diseases are responsible of ap. 50,000 maternal deaths worldwide each year (among some 135 million human pregnancies annually) [1] and infinitely much more human neonatal deaths, notably in poor countries.

For example, in a recent study in the University maternity of the capital of Madagascar, there were during a 8-months follow-up 145 cases of preeclampsia of which 65 (45%) ended in eclampsia (epileptic seizures “grand-mal”) with 7 maternal deaths of young women (24 to 34 years of age), and among eclamptics 40 (61%) neonatal deaths [2].

This discretion is mainly due to the fact that since a century now [3] Eclampsia/Preeclampsia has been considered as “a disease of theories”. As a matter of fact, to date the etiology of this human reproductive disease (and uniquely human, there is no real natural animal models in the other some 4,300-mammal species, including primates or great apes) is still unclear, even if we have done great progresses during the last century [4]. Eclampsia/preeclampsia belong more generally to the hypertensive disorders of pregnancy which affect some 10% human pregnancies (and disappear after delivery), of which 3-5% of total pregnancies complicate with preeclampsia i.e. organ involvement being explained by one central theme ‘endothelial cell dysfunction’: kidney injuries (Glomeruloendotheliosis, proteinuria), liver endothelial inflammation (HELLP) and the endothelial cells involved in the blood –brain barrier (convulsions-eclampsia, occurring in ap. 1% of human births if we let nature do without medical interventions). There are some 6 million preeclampsia worldwide per year, of which ap. 700,000 end in eclampsia. To date, the only definitive treatment is delivery, and we have made almost disappear eclampsia (convulsions) in developed countries at the extreme cost of delivering knowingly and voluntarily often premature or extreme premature babies who have to be cared in intensive care neonatal units. Eclampsia occurs typically at the end of pregnancy in young primiparous mothers and in half of cases before labour [5].

Convulsions represent a dramatic event that evidently catch the attention to the point that it has been reported since the beginning of writings 5,000 years ago (3,000 B.C.) In all continents. In this frame, specifically grand-mal seizures occurring during delivery, have been as such reported in Atharta Veda/Sushruta (India), Wang Dui Me (China), Egyptian Papyrus (Africa), Galen-Celsus-Hippocrates (Europe) [4,5].

Interest for Archaeologists

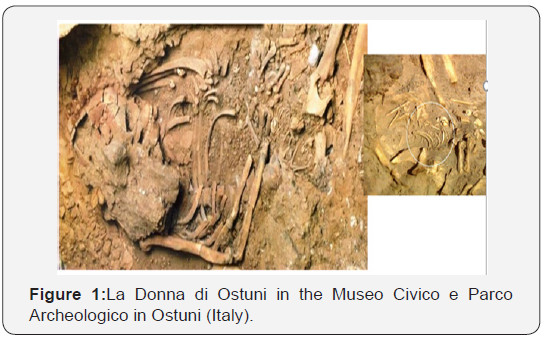

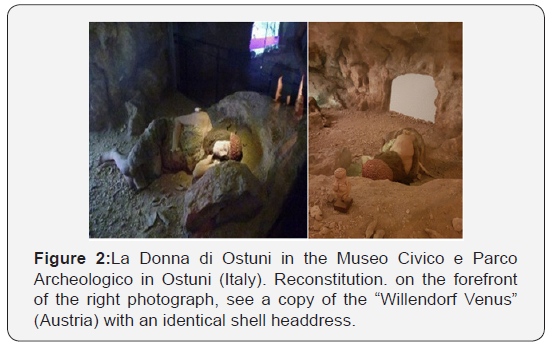

“La Donna di Ostuni.” In 1991, Professor Donato Coppola, an Italian paleontologist, discovered near Ostuni (fortified medieval city uphill between Bari and Brindisi, on the southern Italian Adriatic coast) the skeleton of the human “most ancient mother” ever found, as accepted by all the paleoanthropological community with a 8 month-baby in her uterus. These skeletons were found in the cave “sante Maria d’Agnano”, very close to Ostuni and they are now exposed in the Museo Civico e Parco Archeologico in Ostuni, [6] (Figure 1). The carbon-dating of these human remains are estimated at approximately 28,000 years ago (MAMS 12903, calBC 26461-26115, calBC 26616-25966 B.C) [7]. The 20-year-old mother (all her teeth in good shape) and the baby died together, the foetus of 8 months gestation (45 cm of length) in cephalic presentation showed an extrapelvic head therefore not yet engaged confirming that the event occurred before labour. We proposed recently that the cause of these maternal –fetal deaths may indeed be due to eclamptic fits [8]. There are apparently 2 other locations where foetuses were also found inside their mother’s pelves: Nazlet Khater (Upper Egypt) and possibly Nataruk (Turkana Lake, Kenya).

considered as an evident collective effort for a complex ritual operation, a kind of divinisation of a woman who died during pregnancy [7,9]. The mother was buried lying on her left side, in a crouched position, with her right forearm obliquely placed on her abdomen, her face looking toward the east (Figure 2). A very interesting detail is that this young mother wore a 600-shell headdress (Figures 1 & 2) exactly identical to that found on the “Willendorf Venus” (dated 22,000-24,000 years B.C.) In Austria en 1908, 1000 km up north of the area of Ostuni. Why our ancestors have felt the “necessity” for pregnant women to wear such a headdress? For sure, mankind had since the origin noticed that there were a “Damocles sword” upon every pregnant women, and especially young primiparae, namely that at the end of pregnancy, she could have convulsions and possibly die near delivery. This has certainly terrorized our ancestors, and certainly also, seizures were recognised to start from the head (muscle contractions, visual disturbances, unusual head or eye movements, mouth alteration, loss of consciousness) therefore we may propose that the headdresses, or necklace amulets, that pregnant women wore were probably protective artefacts against these ominous events like death at birth and convulsions.

Joseph Szombathy who found the Willendorf statuette proposed the term of “Venus”, and this name became the standard for all these feminine artefacts [10-12]. Since 1864, some 250 paleolitical “Venuses” have been found all around the Eurasiatic area, some of them wearing also headdresses, like “la Dame de Brassempouy”, “Laussel” in the south of France, the “Venus of Kostienki” and “Avdeedo” in Russia and Siberia, possibly also the “Venus of Parabita” [10,11]. Many of these statuettes were very small and light probably used as necklace amulets. All the feminine figurines might not have been “Venuses” (sort of suggestive sexual artefacts) but rather “Maternas”, protective devices during human pregnancies, also against the terrible, unpredictable and frightening convulsions.

Interest for (Paleo) Anthropologists

It is well established now that a major trigger of preeclampsia (occurring only during the last trimester of the human pregnancy) is linked with a defective placentation at the beginning of pregnancy. As a matter of fact, humans have a natural very aggressive trophoblastic invasion (1/3 of the maternal uterine wall, including the muscle-myometrium). A defective placentation during the first trimester of pregnancy may lead to eclampsia/preeclampsia. Among primates, the haemochorial placentation is linked with the size of the fetal brain [12,13]. Palaeoanthropologists may refer to the debates on the subject concerning eclampsia/preeclampsia [4,14-16] on the different species of hominids and humans. We may then speculate that eclampsia should have existed in Homo erectus, Homo neanderthalensis as well as in Homo sapiens, and probably not in Homo or hominids with lighter fetal brains.

For anthropologists/ethnologists, there is a poorly explored continent which is the knowledge and/or interpretation of eclampsia in different human communities, especially in human groups having still not access to effective modern medical and obstetrical cares (unfortunately, to date, still a majority of humans). Studies have been made in Nigeria [17], Mozambique [18], Pakistan [19] and India [20], but it should have a lot to do further in the future: asking the simple question “what is the cause or meaning of convulsions during pregnancy in young women” to women themselves, but moreover to matrons, healers, community health workers, shamans etc… Tales, myths, different allegories or interpretation on the subject may be a millennial culture which could make us approach how our far ancestor could themselves explain this event. Sending students or post-Doctoral fellows in different parts of the world should probably reveal many surprises for the different interpretations of these fatal convulsions in young women.

Conclusion

Archaeologists and anthropologists must be aware of the existence of this spectacular and frightening complication of human reproduction which is eclampsia [21]. Any woman, even illiterate, has obligatorily heard about it (as it could happen to her). Having this cultural background may help to understand/ interpret some clues (paleolithical statuettes, parietal arts).

References

- Ghulmiyyah L, Sibai B (2012) Maternal mortality from preeclampsia/ eclampsia. Semin Perinatol 36(1): 56-59.

- Ratsiatosika AT, Razafimanantsoa E, Andriantoky VB, Ravoavison N, Andrianampanalinarivo Hery R, et al. (2018) Incidence and natural history of preeclampsia/eclampsia at the university maternity of Antananarivo, Madagascar: high prevalence of the early-onset condition. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 22: 1-6.

- Zweifel P (1916) Eklampsie. In: Dederlein A (Eds.), Handbuch der Geburtshilfe, Wiesbade, Bergman 4: 672-723.

- Robillard PY, Dekker G, Chaouat G, Scioscia M, Iacobelli S, et al. (2017) Historical evolution of ideas on eclampsia/preeclampsia: A proposed optimistic view of preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol 123: 72-77.

- Chesley TC (1978) Introduction, History, Controversies and definitions. In: Chesley TC, Ed. Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. New-York: Appleton-Century-Crofts p. 4-13.

- http://www.ostunimuseo.it/it/museo-civico/

- Nava A, Coppa A, Coppola D, Mancini L, Dreossi D, et al. (2017) Virtual histological assessment of the prenatal life history and age at death of the Upper Paleolithic fetus from Ostuni. Italy, Sci Rep 7(1): 9427.

- Robillard PY, Scioscia M, Coppola D, Chaline J, Bonsante F, et al. (2018) Donna di Ostuni. a case of eclampsia 28,000 years ago? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med 31(10): 1381-1384.

- Coppola D (2012) Il Riparo di Agnano nel Paleolitico superiore. La sepoltura Ostuni 1 ed i suoi simboli, Università di Roma Tor Vergata.

- http://www.ancient-origins.net/ancient-places-europe/venusfigurines- european-paleolithic-era-001548

- Les Venus paléolithiques.

- Cohen C (2003) La femme des origines. Images de la femme dans la Préhistoire occidentale. Belin, Herscher, Paris.

- Cole LA. The evolution of the Primate, Hominid and Human brain. J Primatol 4: 124.

- Chaline J (2003) Increased cranial capacity in hominid evolution and preeclampsia. J Reprod Immunol 59(2): 137-152.

- Robillard PY, Chaline J, Chaouat G, Hulsey TC (2003) Preeclampsia/ Eclampsia and the Evolution of the Human Brain. Current Anthropol 44(1): 130-135.

- Robillard PY, Dekker GA, Hulsey TC (2002) Evolutionary adaptations to pre-eclampsia/eclampsia in humans: low fecundability rate, loss of oestrus, prohibitions of incest and systematic polyandry. Am J Reprod Immunol 47(2): 104-111.

- Akeju DO, Vidler M, Oladapo OT, et al. (2016) Community perceptions of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia in Ogun State, Nigeria: a qualitative study. Reprod Health 8(13): 1-57.

- Boene H, Vidler M, Sacoor C (2016) Community perceptions of preeclampsia and eclampsia in southern Mozambique. Reprod Health 8(13): 33.

- Khowaja AR, Qureshi RN, Sheikh S (2016) Community’s perceptions of pre-eclampsia and eclampsia in Sindh Pakistan: a qualitative study. Reprod Health. 2016 Jun 8;13 Suppl 1:36.

- Vidler M, Charantimath U, Katageri G (2016) Community perceptions of pre-eclampsia in rural Karnataka State, India: a qualitative study. Reprod Health 8(13): 1-35.

- Rosenberg KR, Trevathan WR (2007) An anthropological perspective on the evolutionary context of preeclampsia in humans. J Reprod Immunol 76(1-2): 91-97.