Mesopotamia 2550 B.C.: The Earliest Boundary Water Treaty

Peter H Sand*

Institute of International Law, University of Munich, Germany

Submission: June 10, 2018; Published: July 27, 2018

*Corresponding author: Peter H Sand, University of Munich, Germany, Email: petershsand@t-online.de

How to cite this article: Peter H S. Mesopotamia 2550 B.C.: The Earliest Boundary Water Treaty. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2018; 5(4): 555669. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.05.555669

Abstract

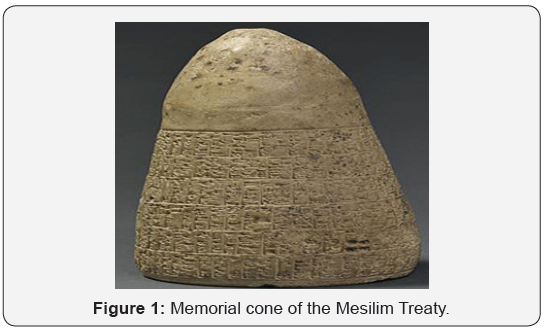

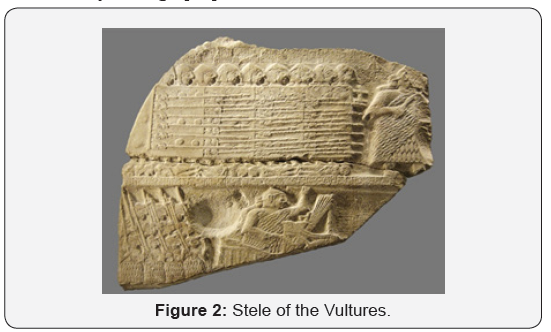

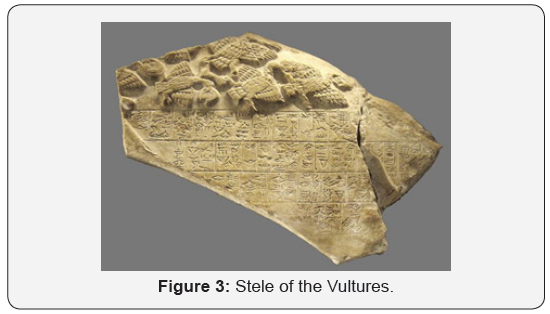

The Musée du Louvre in Paris holds tangible evidence of the world’s first known legal agreement on boundary water resources: viz., the Mesilim Treaty, concluded in the 25th century B.C. between the two Mesopotamian states of Lagash and Umma. The terms of the treaty have been preserved as cuneiform inscriptions on a limestone cone (Figure 1) and a stele commemorating Lagash’s victorious battle enforcing the treaty [1]. Fragments of both artifacts were excavated in 1878-1912 by French archeologists on sites at Tellō (Tall Lawh, Dhi Qar Governate in Southern Iraq), the ancient temple-city of Girsu, once the capital of Lagash [2]. The inscriptions transcribed and translated into French, German, Italian and English [3], turned out to match several other texts on corresponding archeological finds of the period. The key exhibit, the so-called ‘Stele of the Vultures’, depicts Lagash ruler E’anatum leading his army, and vultures devouring slain Umma warriors (Figures 2 & 3).

Keywords: Ancient history; Boundaries; International law; Mesopotamia; Water resources;

Mini Review

Mesilim [or Mesalim, born ca. 2600 B.C.] was the ruler of Kish, a kingdom north of Lagash and Umma, which held a traditional ‘hegemonic’ position in the loose alliance of small adjoining Sumerian city-states in the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, south of what was to become Babylon [4]. Because of the prevailing precarious rainfall conditions, the agricultural economy of the entire delta area has always been crucially dependent on irrigation [5], mainly from the ‘great Tigris’, through an elaborate system of canals and levees which inevitably require close inter-community cooperation. The geographic focus of the bilateral Lagash-Umma agreement, concluded under Mesilim’s authority as external arbiter, was the fertile Gu-edena valley, roughly ten by four kilometers wide and irrigated by Tigris waters from a canal named Lum-magirnunta (probably the modern Shatt al-Hayy) on the border between Umma and Lagash, with boundaries marked by stone steles.

Part of the treaty was a crop-sharing arrangement for a portion of boundary land (some eleven square kilometers) downstream on Lagash territory, that was cultivated by Umma under lease, against payment of an annual rental fee (máš, calculated in silver-shekel equivalents of barley crops) to cover the costs of canal maintenance [6]. However, when Umma repeatedly refused to honor its accumulated tenancy debts, hostilities broke out, resulting in partial destruction of the canal and in unilateral diversions of water upstream. In several successive military confrontations (‘the first known war in history that was, in essence, fought about water’) [7], Umma was ultimately defeated by Lagash (first under the leadership of E’anatum, ca. 2470 B.C.; and later under his nephew Enmetena, ca. 2430 B.C.) [8], and was forced to accept the reconstruction (and extension) of the canal and the reinstatement of the boundaries as originally drawn up by Mesilim.

Alas, the treaty so renewed and ‘writ in stone’, and the peace so re-established, does not seem to have survived for long, and was eventually overtaken and mooted by external political events (the Akkadian/Sargonic invasions) in subsequent generations. Even so, the agreement has been hailed as ‘the first international arbitration’ [9], and as ‘the oldest treaty of which there is a reliable record’ [10]. It remains a unique early attempt at resolving a dispute over boundary waters by formal reference to a superior spiritual order (in this case, the deities of both parties, repeatedly ‘sworn to’ in the text), and hence may indeed qualify as a precursor of international law in this field – well over 4,000 years ago [11].

References

- Nussbaum A (1962) A Concise History of the Law of Nations. Macmillan, New York, USA, p. 1-2.

- Lambert M (1966) Une histoire du conflit entre Lagash et Umma, Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archéologie Orientale 50 : 141-146.

- Thureau-Dangin F (1897) Le cône historique d’Entemena, Revue d’Assyriologie et d’Archéologie Orientale 4 : 37-50.

- King LW (1910) A History of Sumer and Akkad: An Account of the Early Races of Babylonia from Prehistoric Times to the Foundation of the Babylonian Monarchy. Clowes & Sons, London, UK, pp. 101.

- Gruber JW (1948) Irrigation and Land Use in Ancient Mesopotamia, Agricultural History 22: 69-77.

- Strauss M J (2015) Territorial Leasing in Diplomacy and International Law. Nijhoff, Leiden, Netherlands, p. 52-54.

- Elver H (2002), Peaceful Uses of International Rivers: The Euphrates and Tigris Rivers Dispute (Ardsley/NY: Transnational Publishers) p. 8.

- Enmetena [or Entemena] was a son of E’anatu’s brother and successor, Enannatu I. His (headless) statue, looted from Baghdad’s National Museum at the end of the Second Gulf War in 2003, was recovered in the United States and returned to Iraq in 2010; see Steven L. Myers, Iraqi Treasures Return, but Questions Remain, Times (8 September 2010), p. A4, New York, USA.

- Rostovtseff MI (1922) International Relations in the Ancient World. In: Walsh EA (Eds.), The History and Nature of International Relations. Macmillan, New York, USA, p. 31-65

- Doebbler CFJ (2018) Dictionary of Public International Law. Rowman & Littlefield, Lanham/MD, USA, p. 374

- But see the more skeptical assessment by Preiser W (1954) Zum Völkerrecht der vork lassischen Antike, Archiv des Völkerrechts, who views the text as a declaration of victor’s justice rather than an affirmation of mutually binding rules between states 4: 257-288.