At A Crossroads: Queensland Transport in 1924

Jennifer Wilson*

Department of Archaeology, Queensland Museum Network, Australia

Submission: July 03, 2018; Published: July 18, 2018

*Corresponding author: Jennifer Wilson, Department of Archaeology, The Workshops Rail Museum, Queensland Museum Network, Australia, Email: jennifer.wilson@qm.qld.gov.au

How to cite this article: Jennifer W. At A Crossroads: Queensland Transport in 1924. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2018; 5(3): 555664. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.05.555664

Keywords:Crossroads; Transport; Century; Drought; Business; Interdependent; Legislation; Coastal shipping; River transport; Communities; Swamps; Livestock; Population; Queensland

Opinion

This article considers the composition of Queensland’s transport systems during the 1920s, positing events of 1924 as significant markers in the evolution of transport across the state. By the 1920s, Queensland’s major transport systems on sea, river, road and rail, were interlinked and interdependent. The range and rapid development presented challenges for the construction and management of efficient transport systems, with the introduction of new infrastructure, institutions and legislation required at a similar pace and complexity.

For most of its history, from European settlement in 1825, Queensland’s development was less centralised than Australia’s other states and territories. Throughout the nineteenth century, coastal shipping, river transport, roads used by horse and bullock drawn vehicles and a decentralised rail network enabled the expansion and development of communities, along with commercial and industrial enterprises. By 1924, a population of 825,000 had spread over the state’s 1.853 million km² (715447.2998 million mi²), making ever-increasing demands on transport systems across its sub-tropical coastal ranges and swamps, inland plains and rivers that flooded seasonally.

The introduction of motor vehicles presented challenges and changes for horse drawn vehicle transport companies. The last Cobb and Co. coach in Queensland ran from Yuleba to Surat on 14 August 1924. Cobb and Co. coaches began services in Queensland on 1 January 1866, operating to and from the rail lines as they opened at Ipswich, Grandchester, Toowoomba and beyond. By 1900, Cobb and Co. operated 39 routes across 7,750 kilometers (4,815.62 miles) of Queensland, providing transport of passengers, goods and mail. The company began to diversify before its last coach run, purchasing three motor vehicles in 1911 to continue some passenger and mail services, and stores in the towns of Yuleba, Surat, St George, Thallon and Dirranbandi. With increased competition and the beginning of the Great Depression, Cobb and Co. wound up its operations in 1929[1].

The transition from horse drawn vehicles to motor vehicles was not straightforward or final in all circumstances. For some, especially those in regional areas, insufficient access to services, inadequate roads, and periods of increased fuel costs or shortages, meant that horses and bullocks were still in use for years to come. For example, the last Queensland horse mail run, that serviced Coen, north-west of Cookstown, did not finish until 1951[2]. Further, although motor vehicles quickly proved more efficient than teams of horses, carrying goods and passengers over greater distances at greater speeds, horses remained a sentimental favourite. With the final services of Cobb and Co. approaching, numerous newspapers published nostalgic articles about the service. William Muggridge’s poem, ‘The Days of Cobb & Co.’, concluded that ‘The railway train and the motor-car have hustled the coach away’, but his toast to ‘The Pass into which the old days go’ indicated a popular opinion that the former transport service would not be forgotten [3] (Figure 1).

Having opened its first line in 1865, by 1924 Queensland Railways had almost 10,000 kilometers (over 6000 miles) of line open for traffic. In 1924, the North Coast line was completed, providing an unbroken rail connection between Brisbane and Cairns, and that year a general increase in rail passenger, goods and live-stock traffic was attributed in part to greater population and‘an abnormally good season’ for agriculture in North Queensland[4]. Although 1924 was a year of records for cattle transport, economic challenges in maintenance, union strike action and decreased passenger numbers began to place strain on services, and an increase of rail freights and fares that year was widely criticized by business and community groups.

In his report for the year 1924-1925, Commissioner of Railways, J W Davidson, identified a “disadvantage under which the revenues of the Queensland Railways suffered in comparison with other States because of tapering of rates and fares for the extremely long haulage of good and passengers” [4]. Davidson cited the greatest distances at that time by rail from the capital of each state for comparison, with the longest, almost double that of any other state, being Brisbane to Dajarra, Western Queensland, at 2,275 kilometers (1,414 miles). The following year, Davidson concluded that “While a considerable proportion of the falling off was attributable to cessation of traffic during the railway strike, and to the drought prevailing, the rapid expansion of motor traffic is also responsible for loss of business to the railway” [5].

Motor vehicles were first imported to Queensland during the early 1900s. Initially their expense and rarity limited their use to those who could afford the time and money, but by the 1920s a broader range of the population were purchasing and using motor vehicles. Following the introduction of the Main Roads Act in 1920, motor vehicle registrations were managed by the newly-formed Main Roads Commission. By June 1924, 25,052 cars, 1,624 trucks and 4,563 motor cycles had been registered, signifying that cars were “being put into commission almost as fast as they were being imported” [6]. By the end of the decade Queensland’s agricultural produce, livestock and population was increasingly conveyed by motor vehicle.

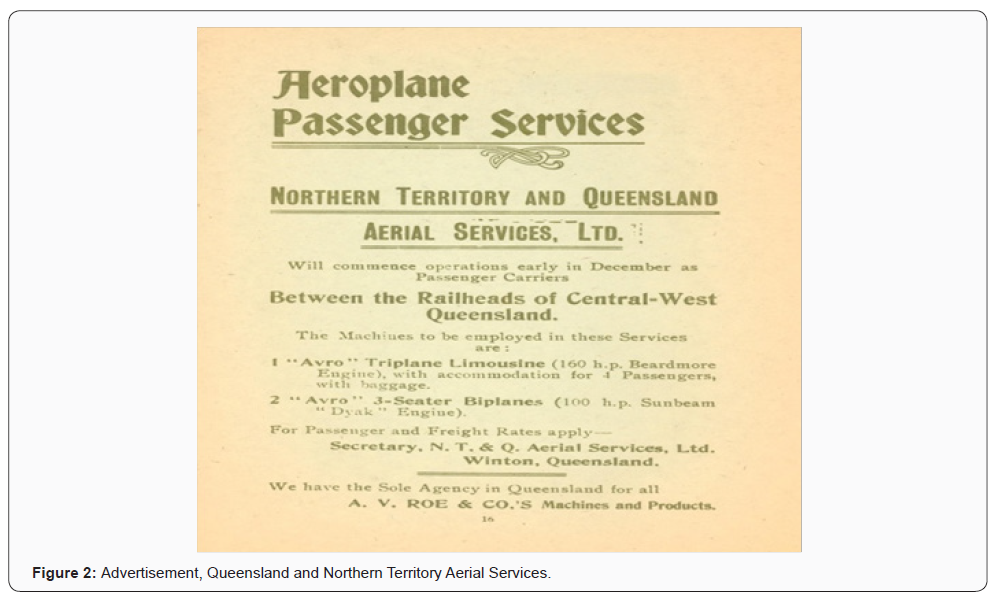

The only real challenge to the increasing impact and dominance of motor transport was that posed by the development of aviation in Australia after the First World War. The 1920 Air Navigation Act designated airfields, standardized aircraft registrations, and called for tenders for airmail carriage under government subsidy on four initial routes that would complement existing rail services, including Charleville to Cloncurry in western Queensland. On 16 November 1920, the Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services Ltd was formed, making its first scheduled passenger and mail flight under the subsidy on 2 November 1922. Soon known by its initials - QANTAS - in December 1924 the company reported that it had successfully flown over 200,000 miles “without injury to passengers or staff” [7] (Figure 2).

In 1924, Qantas introduced a four-passenger de Havilland DH50 on the Charleville to Cloncurry service, the first with an enclosed passenger cabin. By chance, Prime Minister Stanley Bruce was one of the first to passengers to promote the service, becoming the first Australian Prime Minister to use air travel for an official journey in November 1924. At the end of his journey, Bruce stated “The good progress which has been made up to the present and the excellency and efficiency of the services I have just utilized augur well for the future of aerial transport in Australia” [7]. Two years later, Qantas began manufacturing a small fleet of DH50 aircraft, adapted for Australian conditions, and in 1928 Qantas’ DH50 VH-UER was renamed ‘Victory’ and leased for service to the newly established Australian Aerial Medical Service (later the Royal Flying Doctor Service). By the end of the decade, Qantas had expanded its services to Commonweal, Mt Isa and Normanton, built a hangar in Brisbane and opened the Brisbane Flying School [8].

Changes and developments in Queensland’s transport systems during the 1920s represented a unique range of complexities and opportunities across road, rail and sky, especially at their points of intersection. The state enjoyed increasing choice for travel and freight, and by the end of the decade had witnessed widespread transitions from horsepower to motor power, and regular air services that could convey passengers and mail faster and cheaper (in some cases) than rail. Almost 100 years later, with increasing interest in alternate fuels and technologies and integrated transport systems, it is likely that another decade of similar change and development will soon be part of Queensland’s transport history.

References

- Srnicek N (2016) Platform capitalism Place (1st edn), John Wiley & Sons, New Jersey, USA.

- Quaglieri A, Arias A (2016) Unraveling Airbnb: Urban perspectives from Barcelona. In: Russo A, Richards G (Eds.), Reinventing the Local in Tourism: Producing, Consuming and Negotiating Place (1st edition), Channel View Publications, Buffalo, NY, USA, pp. 209-228.