Sri Lanka's Earliest Wild Musa Bananas?

Rathnasiri Premathilake1* and Chris O Hunt2

1Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology, University of Kelaniya, Bauddhaloka Mawatha, Sri Lanka

2School of Natural Science and Phychology, Liverpool John Moores University, UK

Submission: November 01, 2017; Published: March 26, 2018

Submission: April 23, 2018; Published: May 04, 2018

*Corresponding author: R Premathilake, Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology, University of Kelaniya, 407, Bauddhaloka Mawatha, Colombo 7, Sri Lanka ,Tel: 94122694151; Email: premathilake@hotmail.com

How to cite this article: Rathnasiri P, Chris O H. Sri Lanka's Earliest Wild Musa Bananas?. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2018; 3(2): 555608. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2018.03.555608

Abstract

In spite of their importance as a crop today, records of the use of wild banana and the antecedents of the modern domesticated bananas are relatively obscure. Banana dispersal pattern from their native range (e.g. Island South East Asia and New Guinea) is also poorly known. Excavation at Fahien Rockshelter in South Western Sri Lanka yielded phytolith sequence dating from 48,354 to 3900 cal BP. Phytolith evidence suggests that Rockshelter occupants used wild banana (Musa. acuminata and M. balbisiana) through the late Pleistocene to early Holocene, i.e. 8000 cal BP. After this age, occupants significantly decreased the use of wild bananas.

Keywords: Banana; Phytolith; Dispersal; Archaeology; Sri Lanka

Introduction

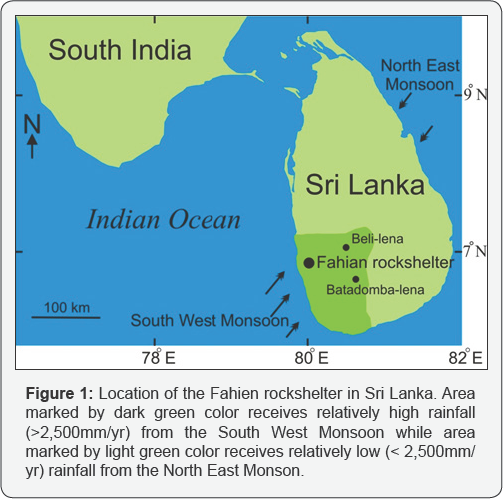

The earliest known banana cultivation is at 6,950-6,440cal BP at Kuk Swamp in the highlands of Papua New Guinea [1]. The dispersal of bananas from Papua New Guinea, the role of human agents and the arrival of the first cultivated bananas in many other geographical areas in the world have so far been poorly documented, but has recently been discussed using data from phytoliths, archaeology, genetics and linguistics [2-7]. Bananas are known from Munsa, Uganda by 5,492-5,100cal. BP [3,8] and Kot Diji, Pakistan by 4,500-3,900cal. BP [5] although their domestication status is unclear. By 2,760-2,300cal. BP, banana had reached Nkang, Cameroon, West Africa [2,9-12]. But the route and chronology are still disputed on chronological [4,13], archaeological [14,15,16,17] historical and linguistic [18-20] and archaeobotanical [13,21] grounds. There is also discussion about the proposed mode of dispersal on terrestrial [6,7,22] and maritime routes [6,7,20,23] from South East Asia to South Asia and Africa. The island of Sri Lanka in the Indian Ocean has evidence of the prehistoric settlements from several Rock shelter sites dating from 36,000cal BP onwards, and one terminal Pleistocene sits yielded a few evidence of wild Musa banana used as one of the starchy food in prehistoric life [24,25], but no conclusive evidence has been presented for understanding the prehistory of wild Musa banana in their native region. This publication reports the very early occurrence of the phytoliths of wild bananas from the late Quaternary archaeological sequence (48,354 -3900cal BP) at Fahien Rock shelter (Figure 1).

Fahien Rockshelter

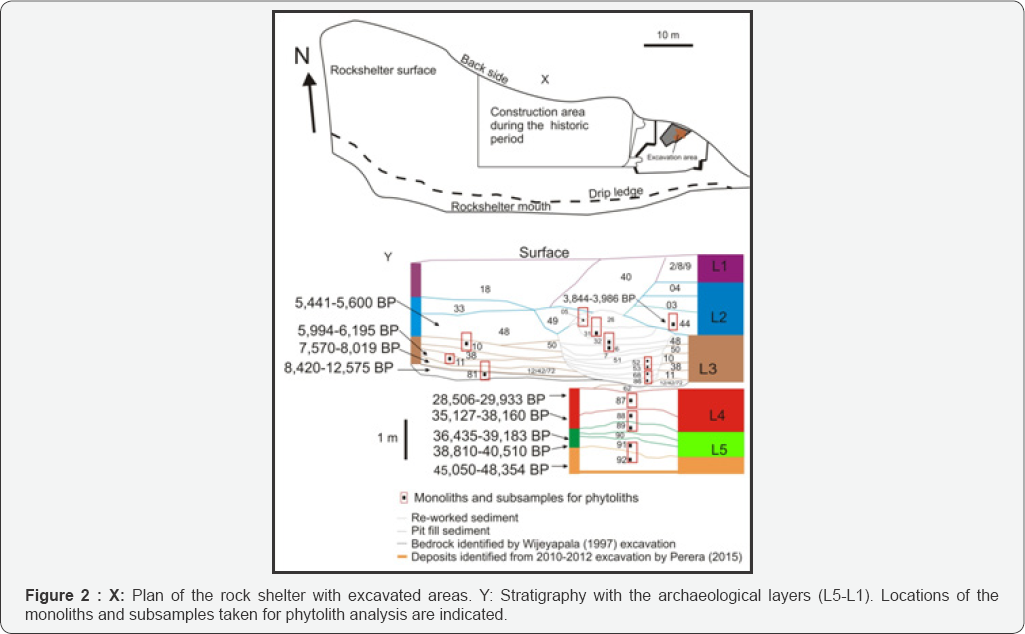

Fahien Rockshelter is situated at 80° 12' 55" E 6° 38' 55" N and 130m above mean sea level in Yatagampitiya village near Bulathsinhala in the Kalutara District, in the humid southwest of Sri Lanka (Figure 1). FaHien Rockshelter is one of the oldest prehistoric sites in Sri Lanka [26,27]. Investigations at FaHien Rockshelter included work on the stratigraphy, sediments, lithics, bone tools, beads, bones, terrestrial and marine shells, charcoal, macrofloral remains (Canarium sp. nuts, Artocarpus sp. epicarps), coprolites, and several interred anatomically modern humans, some coated with red ochre. The rockshelter BP [24-30], and these works identified 6 major layers with deposits also contain several of preserved hearths, palaeofloors approximately 250 archaeological contexts. These were grouped and postholes. The sequence dates from ca. 48,000 to 3900cal into 8 archaeological phases (Figure 2).

Sample Selection, Material and Methods

Eleven 30x10x8cm monoliths were taken from the southern profile of Fahien Rockshelter excavation Area. From these monoliths, seventeen subsamples were selected for phytolith analysis. The composition of the subsamples is generally pebbly loam. Ten of the subsamples were from L2, of middle/late Holocene age. Figure 2 shows the subsample location and the contexts identified within the major layers.

The methods used in this study follow [31]. Sediment samples of 10-15g were used. They were dried at 40 °C for a few hours and passed through 2 mm sieves. The fraction passing the sieve was used. CaCO3 was removed using 10% HCl at 40 °C in a hot water bath and the material was centrifuged at 2000rpm for 5 minutes. The supernatant was decanted and the materials were checked with 1% AgNO3 solution to ensure freedom from CaCO3. The material was oxidized in 40 ml of 30% H2O2 at 80-90 °C in an oven for 2-3 hours. After cooling a few drops of NH4OH solution was added to check for excess H2O2. The resulting suspension was passed through a150|im sieve to remove coarse sand. The fraction less than 150|im was mixed with 20ml 0.5% Na2P2O7.10H2O. Clay particles were removed using density gradient techniques based on Stoke’s Law. The silty fraction was removed and dried. 0.5g of dry materials were mixed with 10ml ZnBr2 solution (density exactly adjusted to 2.35gcm3) in a centrifuge tube. It was allowed to settle for 30 minutes and centrifuged at 2000rpm for 30 minutes. This process allowed separation of phytoliths from silt and other heavy minerals. The phytolith fraction was removed and mixed with 1N HCl and centrifuged at 2000rpm for 5 minutes. The final phytolith fraction was mounted in Canada Balsam and observed under the Olympus BX51 microscope. Micrographs were taken using F-View Soft Imaging System. In each sample, a minimum number of 250 phytoliths were counted at X400. Phytolith morphotype classifications and taxonomic identification were made according to the reference collection from number of modern and wild banana species collected from the flora of Sri Lanka and Royal Botanic Garden, Kew. Comparative studies (shape, size and measurement of volcaniforms) on phytolith morphotypes produced from leaf, seed and fruits were carried out using standard preparation methods [32].

Results and Interpretation

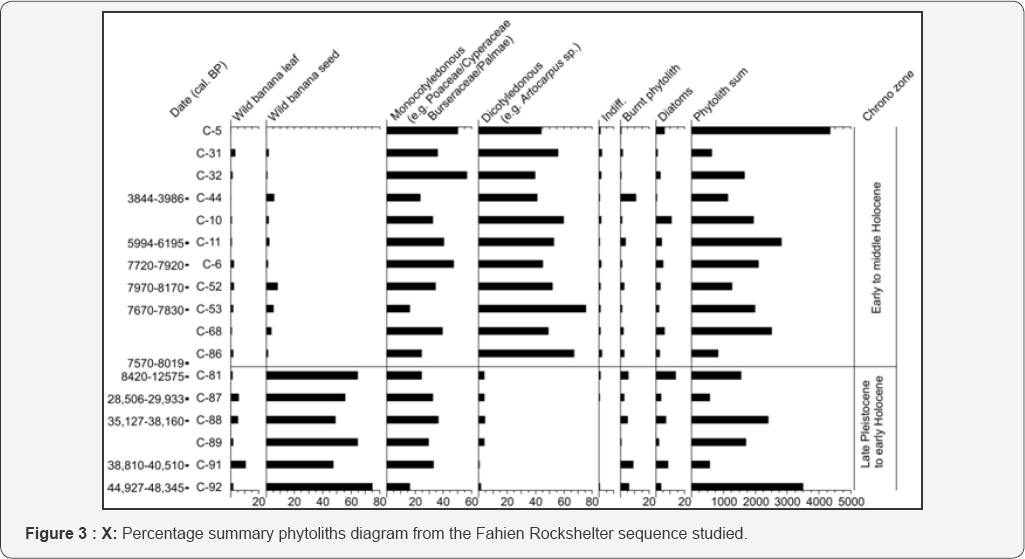

There is secure radiocarbon and OSL dated rockshelter stratigraphy (Figure 2) including lithics, beads, animal and human bones, shell, charcoal, and plant macrofossils of breadfruit (Artocarpus nobilis) epicarps, Carnarium nuts, coprolites, postholes, hearths and two interred individuals coated with red ochre. Banana (Musa spp.) phytoliths from seeds and leaves are present throughout the late Pleistocene-Holocene stratigraphy at Fahien Rockshelter (Figure 3). High percentages of phytoliths of wild bananas and disturbed lowland forest taxa including Palmae, Artocarpus cf. nobilis, Burseraceae/Canarium sp. are evident in all habitation deposits. Phytoliths from woody (e.g. Burseraceae) and weed flora (e.g. Asteraceae, Cyperaceae and Poaceae) occur throughout the sequence. Herbaceous and woody taxa become more frequent just after 8000 cal BP. The phytolith sum also increases at this time. Substantial quantities of burned phytoliths (including Artocarpus sp, Musa spp. and Poaceae) in the late Pleistocene are indicative of frequent fire. Freshwater diatom and few finds of marine diatoms are reported. All these are clearly suggestive of deliberate human activity - import and burning of woody and other plant materials, gathering of wild banana fruits and leaves for multiple purposes (e.g. food, medicine and rituals). The phytolith data demonstrates that wild banana have existed in Sri Lanka for the last 48,354 years. It is not surprising that wild bananas exist as an element in disturbed lowland rainforest and edge habitats from which they colonize disturbed areas in Sri Lanka [33,34]. The occurrence of wild banana phytoliths significantly decreases after 8000cal BP, but they occur in very low percentages through the middle to late Holocene samples suggesting a change of subsistence patterns of Rockshelter occupants.

Discussion

The banana (Musa sp.) is one of the most important commercial crops in the world and its centre of origins appears to lie in Papua New Guinea [1,4,6,7,35]. It is usually said that these bananas seem to have been introduced to all tropical and subtropical regions of the world, where they gained great importance and popularity. In Sri Lanka, 29 banana cultivars and two wild species (M. acuminata and M. balbisiana) have been reported [36-40]. Evidence for wild banana exploitation has been found in the form of their seeds from the terminal Pleistocene samples at Kitulgala Belil-lena, a rockshelter in Sri Lanka [26,41,42]. In Sri Lanka, the antiquity of this tradition is pushed back to 48,000cal BP, as shown by the very significant occurrence of wild banana seed and leaf phytoliths from the late Pleistocene cultural sequence at Fahien Rockshelter. Comparative studies indicate that these banana phytoliths are identical to those found in modern M. accuminata and M. balbisiana populations in Sri Lanka and South India (Figure 4). This phytolith evidence suggests that prehistoric people originally used these two wild banana plants, which probably occurred as natural elements in lowland rainforest in Sri Lanka, both for fruit consumption as well as for other uses such as textile making medicines and rituals [5,43]. It is conceivable that, in the remote past, prehistoric people were responsible for maintaining Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana over Sri Lanka and the Indian Peninsula at very early stage, as suggested by [5,44].

Recent multidisciplinary investigations (genetic, archaeological and linguistic) suggest that Sri Lanka and its wild sub-species (e.g. accuminata subsp. burmannica) are not significant for understanding banana domestication [6,7,22]. Our data, however, suggest that its location in the Indian Ocean is important for understanding the diversity of M. accuminata subspecies and the appearance of semi-domesticated banana, a form of M. accuminata subspecies in Sri Lanka. Because, the great reduction of wild banana phytoliths corresponds to the appearance of phy- toliths comparable with domesticated forms (8000-3900cal BP) which are suggested as semi-domesticated bananas herewith, implies deliberate import and planting activities. It is possible to suggest that new form (s) of bananas emerged through early to middle Holocene. This new form (s) may be a part of domesticated bananas; if so, that would be a great platform to discuss several important issues related to the origin of domesticated bananas in their native regions and dispersal models given in the introductory chapter with this paper [44]. Additional investigations are being conducted to understand those complex issues.

Conclusion

Phytoliths recovered from the archaeological sequence at the Fahien Rockshelter in South Western Sri Lanka show that rockshelter occupants used wild bananas (Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana), most probably for various purposes (e.g. fruit consumption, textile making, medicines and rituals) as early as 48,000 cal BP. Use of wild bananas continued through late Pleistocene to early Holocene, i.e. 8000cal BP. After this age, this tradition significantly decreased with the appearance of new form (s) of bananas.

Acknowledgement

Financial support for RP through a British Academy Visiting Fellowship and National Research Council (NRC-14-43) are gratefully acknowledged. Dr. Senerath Dissanayake, Director General Dr. Nimal Perera, Director Excavation at the Department of Archaeology and Dr. SU Deraniyagala, Former Director General to the Department of Archaeology supported the field sampling and administrative issues. We thank Professors Keith Bennett and Paula Reimer, Queens University, Belfast, for supporting the project. Cooperation received from Mrs. Elizabeth Woodgyer and Mr. Martin Xanthos at the Herbarium Royal Botanic Garden, Kew is appreciated. We thank Mr. WMC Oshan, Chief Excavation Supervisor at the Department of Archaeology and Mr. Asoka Perera and Mr. Sampath Perera at the Postgraduate Institute of Archaeology (PGIAR), University of Kelaniya for field support. RP thanks Professor Jagath Weerasinghe, the Director and the Board of Management at the PGIAR, University of Kelaniya for leave to complete this project. Personal support from Mr. Jim Bradley to RP is much appreciated.

References

- Denham TP, Haberle SG, Lentfer C, Fullagar R, Field J, et al. (2003) Origins of Agriculture at Kuk Swamp in the Highlands of New Guinea. Science 301: 189-193.

- Mindzie CM, Doutrelepont H, Vrydaghs L, Swennen RL, Swennen RJ, et al. (2001) First archaeological evidence of banana cultivation in central Africa during the third millennium before present. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany 10: 1-6.

- Lejju JB, Robertshaw P, Taylor D (2006) Africa's earliest bananas? Journal of Archaeological Science 33: 102-113.

- Donohue M, Denham T (2009) Banana (Musa spp.) Domestication in the Asia-Pacific Region: Linguistic and archaeobotanical perspectives. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 7: 293-332.

- Fuller DQ, Madella M (2009) Banana Cultivation in South Asia and East Asia: A review of the evidence from archaeology and linguistics. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 7: 333-351.

- Perrier X , De Langhe E, Donohue M, Lentfer C, Vrydaghs L, et al. (2011) Multidisciplinary perspectives on banana (Musa spp.) domestication. PNAS 108(28): 11311-11318.

- Perrier X, Bakry F, Carreel F, Jenny C, Horry JP, et al. (2009) Combining Biological Approaches to Shed Light on the Evolution of Edible Bananas. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 7: 199-216.

- Lejju JB, Taylor D, Robertshaw P (2005) Late-Holocene environmental variability at Munsa archaeological site, Uganda: a multicore, multiproxy approach. The Holocene 15: 1044-1061.

- Mbida CM, Neer WV, Doutrelepont, H, Vrydaghs L (2000) Evidence for banana cultivation and animal husbandry during the first millennium B.C. in the forest of southern Cameroon. Journal of Archaeological Science 27: 151-162.

- Mbida CM, Doutrelepont H, Vrydaghs L, Beeckman H, Swennen RJ, et al. (2004) Yes there were bananas in Cameroon more than 2000 years ago. InfoMusa 13(1): 40-42.

- Mbida CM, Doutrelepont H, Vrydaghs L, Swennen RL, Swennen RJ, et al. (2005) The initial history of bananas in Africa. A reply to Jan Vansina. Azania, 40: 128-135.

- Mbida CM, De Langhe E, Vrydaghs L, Doutrelepont H, Swennen RJ, et al. (2006) Phytolith evidence for the early presence of domesticated banana (Musa) in Africa. Documenting Domestication. New genetic and archaeological paradigms. In: Zeder MA, Bradley DG, et al. (Eds.), (University of California Press, Berkeley) pp: 68-81.

- Neumann K, Hildebrand E (2009) Early Bananas in Africa: The state of the art Ethnobotany Research and Applications 7: 353-362.

- Fuller DQ, Boivin N, Hoogervorst T, Allaby R (2011) Across the Indian Ocean: the prehistoric movement of plants and animals. Antiquity 85: 544-558.

- Neer WV (1990) Les faunes de vertebres quaternaires en Afrique centrale. Paysages quaternaires de l Afrique centrale atlantique. In: Lanfranchi R, Schwartz D (Eds.), (Paris, ORSTOM) pp: 195-200.

- Eggert MKH (2005) The Bantu problem and African archaeology. African Archaeology: A critical introduction. In: Stahl AB (Eds.), (Blackwell, Oxford) pp: 301-326.

- Eggert MKH, Hohn A, Kahlheber S, Meister C, Neumann K, et al. (2006) Pits, graves and grains: Archaeological and archaeobotanical research in southern Cameroon. Journal of African Archaeology 4: 273-298.

- Vansina J (2003) Bananas in Cameroon c. 500 B.C.E? Not proven. Azania 38: 174-176.

- Diamond J, Bellwood P (2003) Farmers and Their Languages: The First Expansions. Science 300; 597-603.

- Blench R (2009) Bananas and plantains in Africa: Re-interpreting the linguistic evidence. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 7: 363380.

- Vrydaghs L, Swennen RO, Mbida C, Doutrelepont H, De Langhe E, et al. (2001) The banana phytolith as direct marker of early agriculture. A review of the evidence, Phytolith and Starch Research in the Australian- Pacific-Asian regions: The state of the art. In:Hart DM, Wallis LA (Eds), (Terra Australis 19, Pandanus Books, Canberra) pp: 17-185.

- De Langhe E (2007) The establishment of traditional plantain cultivation in the African rain forest: A working hypothesis. Rethinking Agriculture. In: Denham TP, Irarte J, Vrydaghs L (Eds.), (Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek, CA) pp: 361-370.

- De Langhe E (1995) Banana and plantain: The earliest fruit crops? INIBAP Annual Report. International Network for the Improvement of Banana and Plantain (Montpellier) p: 6-8.

- Perera HN (2010) Prehistoric Sri Lanka: Late Pleistocene Rockshelters and an Open Air Site. BAR International Series. (Archaeopress, Oxford).

- Perera N, Kourampas N, Simpson IA, Deraniyagala SU, Bulbeck D, et al. (2011) People of the ancient rainforest: Late Pleistocene foragers at the Batadomba-lena rockshelter, Sri Lanka. Journal of Human Evolution 61(3): 254-269.

- Deraniyagala SU (1992) The Prehistory of Sri Lanka: An Ecological Perspective: Part I and II (Department of Archaeological Survey, Colombo).

- Wijeyapala WH (1997) New Light on the Prehistory of Sri Lanka in the Context of Recent Investigations of Cave Sites. PhD. Dissertation, University of Peradeniya.

- Kinnaird TC, Sanderson DCW (2010) Luminescence Dating of Sediments from the Fahien-lena Rockshelter, Southern Sri Lanka. (Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre, East Kilbride) p: 1-25.

- Perera HN (2015) The Importance of Sri Lanka Wet Zone Rocksheters. Piyasatahan. In: Dissanayake S, Rev. Chanaloka P, Kodituwakku N, (Eds), (Department of Archaeological Survey and Ministry of Cultural Affairs, Colombo) pp: 104-117.

- Oshan WMC (2011) Stratigraphical analysis of FaHien Rockshelter in Sri Lanka: comprising stratigraphy excavated in 1988 and 2009. MA dissertation, the Department of Archaeology, Decan College Postgraduate Research Institute, Pune, India.

- Lentfer CJ, Boyd WE (1998) A Comparison of Three Methods for the Extraction of Phytoliths from Sediments. Journal of Archaeological Science 25: 1159-1183.

- Ball T, Vrydaghs L, Houwe IVD, Manwaring J, De Langhe E (2006) Differentiating banana phytoliths, wild and edible: Musa acuminata and Musa balbisiana. Journal of Archaeological Science 33: 1228-1236.

- Itino T, Kato M, Hotta, M (1991) Pollination Ecology of the Two Wild Bananas, Musa acuminata subsp. halabanensis and M. salaccensis: Chiropterophily and Ornithophily. Biotropica 23(2): 151-158.

- Ge XJ, Liu MH, Wang WK, Schaal BA, Chiang TY (2005) Population structure of wild bananas, Musa balbisiana, in China determined by SSR fingerprinting and cp DNA PCR-RFLP. Molecular Ecology 14: 933944.

- Lebot (1999) Biomolecular evidence for plant domestication in Sahul. Genetic Resources and Crop Evolution 46: 619-628.

- Hooker JD (1872-1897) The Flora of British India. 7 volumes. (Reeve and Co, London).

- Chandraratne MF, Nanayakkara KDSS (1951) Cultivated varieties in Ceylon. Tropical Agriculturist 107: 71-91.

- Simmonds NW (1956) Botanical results of the banana collecting expedition, 1954-5. Kew Bulletin 11(3): 463-490.

- Simmonds NW (1962) The Evolution of the Bananas. Tropical Science Series (Longmans, London).

- Cheesman EE (1947) The classification of the bananas. Kew Bulletin 2: 97-117.

- Kajale MD (1989) Mesolithic exploitation of wild plants in Sri Lanka: Archaeobotanical study at the cave site of Beli-Lena. Foraging and Farming: The Evolution of Plant Exploitation, eds Harris D, Hillman G (Unwin Hyman, London) pp: 269-281.

- Kourampas N, Simpson IA, Perera N, Deraniyagala SU, Wijeyapala WH (2009) Rockshelter Sedimentation in a Dynamic Tropical Landscape: Late Pleistocene-Early Holocene Archaeological Deposits in Kitulgala Beli-lena, Southwestern Sri Lanka. Geoarchaeology 24(6): 677-714.

- Kennedy J (2009) Bananas and people in the homeland of genus Musa: Not just pretty fruit. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 7: 179197.

- De Langhe E (2009) Relevance of banana seeds in archaeology. Ethnobotany Research and Applications 7: 271-281.