From Sojourners to Settlers: A Qualitative Study of the Homes of Italian Migrants in Brisbane

Raffaello Furlan* and Laura Faggion1

Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University, Qatar

Department of Environmental Planning, Griffith University, Australia

Submission: May 05, 2017; Published: October 16, 2017

*Corresponding author: Raffaello Furlan, Department of Architecture and Urban Planning, Qatar University, Doha, State of Qatar, Qatar, Email: raffur@gmail.com

How to cite this article: Raffaello Furlan, Laura Faggion. From Sojourners to Settlers: A Qualitative Study of the Homes of Italian Migrants in Brisbane. Glob J Arch & Anthropol. 2017; 2(1): 555579. DOI: 10.19080/GJAA.2017.02.555579

Abstract

This research study focuses on the architecture of the domestic dwellings built by a group of twenty first-generation migrants, natives of the Veneto region in Italy. This group migrated to Australia after WWII and built their houses in the 1980s and 1990s in Brisbane. The study looks at the material realm of these houses, that is, their facades, the internal and external organization and use of spaces, as well as at the symbolic realm that corresponds to the meanings attributed by the Veneto people to their houses in Brisbane. The project is of qualitative nature and as primary sources of data uses

- Semi-structured interviews, associated when circumstances made this possible.

- Photo-elicitation interviews and

- Focus group discussion.

The study argues that home is a physical structure and a set of meanings where these two components are tied together rather than being separate and distinct. It shows that there were two models the Veneto migrants chose for the erection of their houses in Brisbane and these correspond to:

- The rural houses built in the 1970s and 1980s by their family and friends in the Veneto region and

- The villas designed for noble families by the architect Andrea Palladio in the 15th century in the homeland of the respondents.

Keywords: Italian migrants; Australia; Transnational houses; Qualitative methodology

Background

Migration is a relevant topic for Australia, as this nation implemented one of the largest immigration programs in the second half of the 20th century, in order to double its size within a short period of forty years [1-9].

Of all migrant groups who came to Australia during this period, the Italian group has been one of the most numerous [10-13] and its physical presence in the urban territory is observable in public places with, for instance, pizzerias, restaurants, ice-cream parlours, food shops and so on [14-15]. Here, the Italian migrants are seen to have annexed their characteristic culture to the Australian society, a modus operandi which concurrently offers continuity with their native country and adds variety to Australian life [16-20].

Yet the effects of Italian migration on the Australian urban landscape are visible also in migrant’s private places, such as their homes and this has been barely documented prior to this study [21-28].

The Research design

The aim of this study is to outline the research design underpinning this study. The research design involves bringing together various elements which are: knowledge claim; general strategies of enquiries; specific data collection procedures appropriated for the study; data analysis procedures; and reporting the findings.

Knowledge tradition: Constructivist knowledge claim and qualitative nature of the study

The first step consists of clarifying which knowledge claims also called paradigms, philosophical assumptions, epistemologies and ontologies-under pin the current research. Creswell [28] discusses four knowledge claims:

- Post-positivism;

- Pragmatism;

- Advocacy/participatory

- Constructivism.

In this research, the purpose of Research Question #1 is to access information on the personal experiences of migrant people, their homes, their culture and goal of Research Question #2 is to assess the meanings people have attached to their homes. Due to the nature of this information, the latter could not be accessed by a scientific approach behind post-positivism and, therefore, also behind pragmatism, which implies the collection of both quantitative and qualitative data. At the same time, this study is concerned with a migrant group, and that could suggest an advocacy/participatory approach. However, this is not the case since the enquiries are not intertwined with themes such as marginalization, inequity, suppression, politics or the political agenda behind this approach. Instead, because of the particular topics of this research and the authors’ personal assumptions concerning how to access the information needed, this study is in-line with constructivism. In discussing constructivism, [29- 30] identify some important assumptions including:

- The researcher focuses on specific contexts in which people live and work in order to understand the historical and cultural settings of the participants.

- The researcher focuses on an exploration of the way people interpret their experiences in the world in which they live.

- People make sense of their world based on their historical and social perspective-we are born into a world of meaning bestowed upon us by our culture.

How to access information

- The goal of the researcher is to rely as much as possible on the participants’ view of the situation being studied.

- The question becomes broad and general so that the participants can express their views.

- The researcher gathers information personally and listens carefully to what people say.

- Knowledge is constructed jointly in interaction by the researcher and the participants through consensus. Multiple realities are presupposed, with different people experiencing them differently.

Based on these characteristics, this epistemology is retained as being useful for the current research because it allows the researchers to explore and interpret the relationship between the participants in this study, their culture and homes, relying as much as possible on their views.

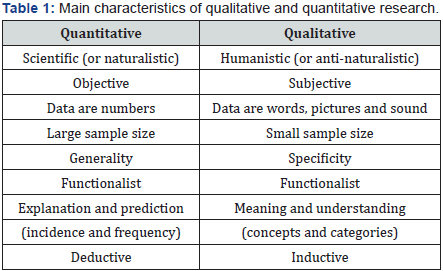

According to [31-32], a constructivist epistemology implies research of a qualitative nature. Qualitative methods can be understood as being the title of a social movement, a banner around which people in social and cultural research communities have mobilized with a particular energy from the late 1960s onwards in Western social research [33]. In the 1950s and 1960s scholars interested in more interpretative approaches felt threatened by the scientific approach and developed a ‘qualitative creation myth’ that contributed to the separation between qualitative and quantitative methods [34]. Table 1 summarizes the main characteristics of qualitative and quantitative research.

Source: Adapted from Kitchin & Tate [43].

In this research study, questions considering migrants, their homes, their culture and the meanings they attached to these homes cannot be answered by a quantitative study. This is because those studies employ a scientific approach that requires numerical data, statistical techniques, a large population size and an interest in generalization. Because of the topics researched here and the need to hear the opinions of migrants, it is argued that this study must be approached using qualitative techniques which are concerned with a humanistic approach and a small sample size. This, in turn, allows an investigation into the perspective of the study participants, subjectivity, specificity, and interpretation of meanings and a deeper understanding of the situation being studied.

Qualitative strategies of enquiry

The second major step in the research design is to define the strategies of enquiry (2003) or methodologies (1998). Qualitative research typically employs five major strategies: case studies; ethnography; phenomenology; grounded theory; and narrative research [35]. The choice among these strategies has been built on [36] for Research Question #1 and [37] for Research Question #2. In her PhD on migrants and public and private places in Sydney, [38] used phenomenology in three ethnographic case studies. A parallel tract used in her research was hermeneutics, which is the study of interpretations. [39] in her research conducted in Sydney on migrant women and the meaning of their homes also included phenomenology and hermeneutics as part of her research methodology. Therefore, building on work of these two scholars, the strategies used for the current research are ethnography, phenomenology and case study, combined to form a set of qualitative ethnographic case studies which generate the data that is interpreted using phenomenological hermeneutic as the analytic tool.

Ethnography

Ethnography focuses on the culture of people as a collection of belief, behaviors, operational systems etc. [39]. Indeed, the term ‘ethnography’ literally means “a description of people or cultures” [40]. Here, the normal and unspectacular aspects of everyday life are recognized as being equally worthy of study as are special events [41]. Ethnography also documents the world in terms of the meanings held by the people in it (2004). Therefore, the ethnographic approach is a suitable strategy to use in answering the two research questions posed by this study.

Ethnographic knowledge production began in anthropology with pioneers such as Malinowski [42-43] & [44] who inaugurated and encouraged the practice of spending a lengthy period of time-a year and more-with the population under investigation. Later, sociologists also introduced ethnography into their research enquiries [45-46]. In this last context, the most famous example is the work of the Chicago School (1920s to 1940s), under the direction of Park and Burgess, which focused on members of the large, culturally diverse urban communities that formed in American cities at the end of the nineteenth century. Here, a widely cited ethnographic study is the exemplary work, Street Corner Society by Whyte [47] which gives a picture Italian Americans living in Boston. With the passing of the years, ethnography has presented opportunities not only for anthropological and social studies but also for cultural research where scholars have applied it in a modified form.

Ethnography involves direct contact with people and places. Therefore the main advantage of this strategy is that once the researcher has interacted with the participants in the study and gained their knowledge, the study produces rich and detailed descriptions of real life situations which stand in their own right without the need to worry about how representative the situation might be [48]. On the other hand, a weakness of this method consists in the collection of data that is (if done in the classical method) time consuming and expensive. However, today especially in social studies and cultural research, the ethnographic strategy has been modified to a more modern approach [49]. This means that ethnography has been adapted from the original anthropological large scale tribal settings to small scale urban settings, called mini-ethnographies. Miniethnography seeks to understand and describe only certain aspects of the culture of the participants under study. In this way, the investigation is limited only to a situation or a phenomenon, shortening the time taken for field data collection [50]. This is the type of ethnography used in this study, which focuses on certain phenomena and aspects of the Italian culture belonging to the Italian community who have settled in Brisbane. For Research Question #1 these correspond to the migration from Italy to Australia (which implies the culture of migration) and building a home in the host country (which implies the Italian and Veneto building culture) and for Research Question #2, to the meanings attached to their homes by the migrants (also here are visible some aspects of the Italian culture of the respondents). Thus, this particular type of strategy allows the researchers to focus on some aspects of Italian culture belonging to the Italian community in Brisbane only, with the advantage of saving a considerable amount of time.

Phenomenology

Similarly to ethnography, phenomenology is also relevant to the current study and the two approaches are intimately connected. The phenomenological approach has proved to be useful for research in areas such as health, education and business, where the researcher wants to understand the thinking of the participants [51]. Phenomenology has also been applied in cultural studies, art and design, legal studies, sociology and cultural geography [52]. In particular, for cultural geography and its branch of humanistic studies, both the basis of this study, this strategy is seen as the “foundation for human geography” [53] so that the majority of the work in this area is associated with phenomenology [54]. Phenomenology has been introduced in cultural geography by Tuan [55], Relph [56-57] & Seamon [58-59]. These humanistic geographers saw phenomenology as a viable alternative to the people-less and dehumanizing positivistic and behavioral approaches being adopted at that time in their discipline. They adopted variations of classical phenomenology [60], variations of which the researchers will return to below.

Suggests that phenomenology is a strategy to use when the researcher wants to explore, describe, communicate and possibly interpret the rich detail of people’s experience of a phenomenon- and its hidden meaning - and when the phenomenon under investigation offers little in-depth data. For [61], “phenomenology is a worthy project in its attempt to return the things themselves and to try to create a feeling of understanding for a phenomenon” (p. 10). [62] Describes this strategy as a “people-centered form of knowledge” (p. 24), that is, the phenomenological researcher needs to try to see the world from the point of view of those who experienced the phenomenon, and this is achieved by talking to them about their life experiences related to the object of investigation. This strategy considers paramount the people’s thinking and this is “given credibility and respect in its own right as valid. It is not treated as a less rational than or inferior to the ‘scientific’ thinking of the social researcher, but is considered as rational in its own terms of reference”. Rather than being treated as the foundation for sophisticated theories, that thinking becomes the topic of investigation in its own right. Speigelberg [63], one of the contemporary authorities on the phenomenological movement, states that “all phenomenology takes its start from the phenomena. A phenomenon is essentially what happens to someone, that is the subject” (p. 75). According to [64], a phenomenon is a thing that is known to us through our senses. It is seen, heard, touched, smelled and tasted. It is experienced directly, rather than being conceived in the mind as some abstract concept or theory (p. 77).

Translating this to the current research, there are two phenomena: the first is migrating from Italy to Australia; and the second is building a home in the host country (Research Question #1). To complement this, the research also considers the meanings attached to their homes in the host country by the migrants (Research Question #2). On this last point, a number of authors stressed the point that in investigations involving architectural objects phenomenology provides an approach that does not limit itself to consideration of the form, but also addresses the relationship between the building and the dweller [65-66]. In fact, in phenomenology, a place is not simply a region of space, but is understood to be experienced by people to have meanings [67-68]. These meanings are explored in Research Question #2.

This approach offers the strength of documenting authentic life experiences about a phenomenon in a manner deep enough to reflect the complexity of the social world. Moreover, carrying respect for the people involved in the study, the phenomenological approach assures equity. Not surprisingly, this strategy is criticized for its reliance on the subjects being able to communicate their interpretations. However, contends that the participants in her study, notwithstanding the language barrier, had quite profound observations. Another weakness is that the researcher must clarify which form of phenomenology is being used [69]. This clarification is provided below.

There are several forms of phenomenology: classical/pure/ realistic/transcendental; existential; and hermeneutic. The development of classical phenomenology is attributed to the philosopher Edmund Husserl (1859-1938). His main concern was first-person everyday experiences, with a focus on how we come to know the world. He investigated this through the concept of life world (lebenwelt) which is the world of everyday lived experience verbalised with everyday language [70]. Husserl suggested forms of investigations which rigorously dissected the phenomena with processes of reduction into essences, and argued for the importance of studying the phenomena as they are consciously experienced without preconceptions, presuppositions or preconceived theories about their causes [71-72]. Pure phenomenology necessitated bracketing out all assumptions. This enables a state of consciousness to emerge which clarifies the vision of the essence of the phenomenon. Husserl’s phenomenology included geometry and mathematics in the abstraction of the essences, and he considered his phenomenology to be a disciplined science. He provided a powerful and rigorous alternative philosophy to positivism, so far lacking in humanism [73].

Husserl’s pupils have softened his strict approach by proposing phenomenological alternatives less focused on the transcendental and more on the immanent [74]. These alternatives are existential phenomenology and hermeneutic phenomenology. Existential phenomenology (Jean-Paul Sartre, Martin Heidegger, Maurice Merleau-Ponty) questions Husserl’s consciousness underpinning the experience that views these as a cerebral reconstruction in the mind. This approach sees consciousness not as a separate entity but as being based on human experiences of everyday life and linked to human existence. In contrast, hermeneutic phenomenology (Martin Heiddegger, Hans-Georg Gadamer, Paul Ricoeur) drew from the study of interpretation, known as hermeneutics, naming this investigation hermeneutic phenomenology. Hermeneutic phenomenology “investigates the interpretative structures of experience of texts, whether public, private”. Here, bracketing does not occur, but what the researchers can do is to keep a reflective journal recording their own experiences, personal assumptions and views and try to moderate their impacts as much as they can. Returning to my research, used hermeneutic phenomenology in her study arguing that this strategy advances the understanding of how the experience of migration results in places encoded with that experience, and that hermeneutic phenomenology “can both broaden and deepen perceptions about migrant place making” (p. 108). Likewise Thompson [75-76] used hermeneutic phenomenology in her investigation involving the relationship between people, places and meanings of home held by migrant people. Similarly to Armstrong and Thompson, in this study the use of hermeneutic phenomenology deepens our understanding about migrant place making in Australia.

To sum up phenomenology can be summarised as focusing on subjects’ descriptions of their lived experiences about the phenomenon of migration linked to the phenomenon of building a home in the host country and its associated meanings while hermeneutic phenomenology interpret these experiences.

Case Study

The last strategy of enquiry relevant to this research is the case study. The case study has been utilized in psychology, sociology, political studies, social science, business, community planning and cultural geography [77]. [78] notes that with a case study approach the researcher explores in depth an event, an activity, a program, a process or one or more individuals. To this list [79] adds episodes, institutions and also buildings. [80] suggests that the case study is the preferred strategy when the “focus is on a contemporary phenomenon within some real-life content” (p. 1). With this array of definitions, the first interest of this research-corresponding to the experience of migration-fits under ‘event’ and ‘contemporary phenomenon’, while the second interest-corresponding to building a home in the host country - fits under ‘event’, ‘activity’, ‘building’ and ‘contemporary phenomenon’. To have continuity with the language used above the researchers consider them as contemporary phenomena.

One of the strengths of the case study approach is that it does not dictate which methods to use, but encourages the researcher to utilize multiple methods depending on the study needs. Criticisms have been raised from some quantitative researchers because it is not possible to generalize from case study findings. However, on one hand [81] argues that in a qualitative study, generalization is not a priority. [82] suggests that if we need to make generalizations on the basis of case studies, some of the responsibility falls to the reader: “the reader of the findings will use the information to make some assessment of how the findings have implications across the board for all other type, or how far they are restricted to just the case study example” (p. 44).

Also with the case study research it is important to clarify which type of cases the research has utilized. [83] distinguishes between exploratory, explanatory and descriptive case studies. Very few researchers have investigated the Italian community in Australia and the phenomena analysed in this study, and no research has been conducted into the Veneto group in Brisbane or its domestic architecture, therefore it follows that the most appropriate type of case study for the present study is an exploratory one. Yet it is possible to undertake a case study which is also ethnographic in nature [84] as done by Armstrong and Thompson [85-88]. Therefore, as a whole, this research covers a series of ethnographic and exploratory case studies, each of them being the subject of an individual case study. In this way the research can also be described as utilising ‘multiple case studies’ [89].

Subjects, objects and location: Veneto migrant families and their homes in brisbane

The experience of migration and building a home in the host country with its associated meanings are investigated within an Italian group from the Veneto region, who is now settled in Brisbane. Veneto is a region located in the North East Italy. The researchers have purposefully chosen to narrow the study to only one Italian regional group, rather than concentrating on the large pan-Italian community of Brisbane, not only because there is paucity of research on this particular population in South East Queensland, Australia [90], but also because in Italy, life, people, language, culture, style of cuisine and architecture have a regional character. In fact, each of the twenty regions in Italy has a distinctive culture. This is confirmed by the writing of Mangano [91].

Offered another reason for choosing the Veneto population. They highlight in their analysis of Italian migration to Australia that the Veneto people were overwhelmingly involved in the building industry. Other Italians, for example the migrants from Puglia, were involved in fishing, and migrants from the Aeolian Islands were involved in the fruit and vegetable retailing business [92]. Therefore, the involvement of the Veneto people in that specific industry has made the researchers presume a certain degree of competence on their behalf in the main topic of interest in this study (building a home in the host country), and helped in choosing this particular Italian regional group of migrants.

Because this is an exploratory study, among the various typologies of houses that the migrant group built in Australia, the researchers have chosen to investigate the ‘detached house on a quarter block’ which is the most common type of housing built in Queensland. It is anticipated that the findings of this study will focus on houses of a vernacular nature. In the past, pioneers scholars in vernacular architecture have been [93], who also advocated the importance of studying not only the architecture conceived by famous architects, but also the vernacular ones. More recently [94] defended research on this topic. After more than half a century of debate on what is ‘vernacular architecture’, it seems that there is some agreement on its definition. For vernacular architecture is a non-professional form of housing where architects are not involved. Other scholars have made a similar distinction, defining vernacular architecture as ‘traditional’ architecture, architecture without architects, ‘nonpedigreed’ architecture, and ‘non-academic’ architecture. For the most fundamental principle of this type of architecture is the fact that the buildings are not architect-designed but are constructed by members of societies, thus they may be defined simply as “the architectural languages of the people” (p.1). All of these scholars agree on the definition of vernacular architecture as a non-professional form of housing. Moving the discussion on vernacular architecture to a migrant context, [95] says that, in some cases, it is hard to draw a clear line between professionally designed environments and non-professionally made environments. He defines the migrant houses in his study as part of popular architecture because migrants involved professionals-architects-in their applications for building permits required, however their houses were self-made by the migrants. In this case, it is not vernacular architecture anymore but popular architecture. However, if a builder is involved instead of an architect, the dwelling is then considered to be vernacular (2007). This last view is also supported by Oliver [73].

The houses belonging to the Veneto migrants have been built in Brisbane, the capital of Queensland and the third largest city in Australia. When the researchers began this study they were aware that, statistically, the majority of Italian people live in Melbourne, Victoria, and Sydney, New South Wales [1]. However, Brisbane has been purposefully selected as the location for this research because there is lack of research into the Veneto community and the houses built by them [76].

Recruitment of participants, presentation of cases and position of the researcher

The participants for this study were recruited from the Veneto Association - within the Italo-Australian Club-in new market, Brisbane. The Veneto Association is a regional club that the Veneti regularly frequent, and with which they are highly involved. Helped by the president of this association, the researchers organized and held an information session.

During this recruitment phase, ten cases were purposefully selected to answer the questions of the current research on the basis of the four characteristics explained above: the participants had to be from the Veneto region; they had to be first generation Italians; they had to have migrated to Australia during the mass migration period; and had to have lived the experience of having built their home in the host country. The participants in this study were part of a homogeneous group of ten families - ten men and ten women-originally born in small villages located in the Veneto region, and who migrated to Australia after the Second World War. They are all first-generation Italians and their ages ranged from 72 to 78 years. They all married in Italy after the Second World War and all of their children were born in Australia. They are all Christian Catholics, middle-class and they all have built their houses in the host country.

Material for this study also came from a different source, as a way of triangulating the data. This second source is constituted by other five families-five men and five women - living in Italy in various rural villages located in the Veneto region. Therefore, this study comprises thirty participants in total: twenty from the main group and ten from the current group. This second set of informants was found through the snowballing technique, as they were referred by the migrants in Brisbane, who are their friends. The former participants were all born in Veneto but have never migrated to other countries. They are the same age group as of the migrants in Brisbane and are all married with children born in Veneto. They also are all middle class Christian Catholics. Finally, these participants have all built their homes in the Veneto region.

Data collection procedures

The third major element is the data collection method. While case studies do not dictate any specific method, phenomenology suggests data collection procedures such as: in-depth interviews with people who have experienced the phenomenon in question; observation of the human experience; and documentation including literature, poetry, biography and material culture. Ethnography adds the possibility of using focus group discussions. As a way of validating conclusions, many qualitative methodologies employ multiple methods, or triangulation. For example, relies on discussion groups and interviews because, she argues, these two methods allow for interaction between the researcher and the migrants. Like Armstrong, the researchers also made use of these two methods, allowing the researchers to gather opinions on the experiences related to migration and place making as well as the meanings associated with home in a migrant context. However, unlike Armstrong the researchers have also utilised two other research methods: photo-elicitation interviews and documentation. Thus for this research the researchers have used: semi-structured interviews associated, when circumstances made this possible, with photo-elicitation interviews, and focus group discussions. These primary data are supplemented by secondary data in the form of photographs and drawings.

Interviews: semi-structured and triadic

Byrne [77] suggests that this method tends to be used by scholars who come from an ontological position which appreciates people’s knowledge, values and experiences as being meaningful and worthy of exploration. Patton [78] Identify four interview types: the closed-ended quantitative interview (questionnaire); the structured interview; the semi-structured interview; and the unstructured interview (or informal conversational interview). Quantitative interviews may be too tight and there is the risk of leaving out meaningful data, while unstructured interviews can be too loose and carry the risk not being able to cover all the important information needed for the research. The structured interview, with a fixed order of questions and limited responses with pre-coded answers are comparable to a questionnaire however it is administrated face to face. Moreover, as some researchers argue, with structured interviews there is a risk that particularly interesting responses cannot be followed up in more detail (2000). Based on these critiques, the researchers have opted for using semi-structured interviews. With this type of interview the researchers still have a clear list of questions to be answered as in structured interviews, however, the researchers have some flexibility as to the order in which the topics are considered. A second advantage is that the answers are open-ended, giving the participants freedom to elaborate on points of interests, to develop ideas and to speak their minds on issues they find important. Finally, since all the interviewees are asked the same questions, this interview form provides a natural basis to organise and analyse the data.

According to, the most common form of interview is the one-to-one which involves a meeting between the researcher and one respondent. However, since in the current research participants constitute married couples, this type of interview would have doubled the time spent interviewing. Moreover, Warren & Karner [79] warn that, in interviews involving married couples, some issues might arise if both spouses are not present at the interview. For example, one spouse might seek access to confidential information about the other. To avoid this issue, the researchers have used ‘triad interviews’ -interviews with three people: the husband, wife and researcher. The researchers also took care to stop the interview if one member of the couple needed to leave, and resumed it on their return. A triad interview is undertaken very much like a one-to-one interview in the sense that the researcher remains the focal point of the interaction. The difference between these two types of interviews consists of the fact that, instead of each question prompting a response from just one person, the researcher gets two responses from two people during the interview.

Photo-elicitation interviews

During qualitative interviews, photographs can be shown to participants for the purpose of exploring their values, beliefs, attitudes and meanings [80]. One term for this relatively new strategy is ‘photo elicitation’ and is considered to be a simple variation of open-ended interviews [80]. This method has previously been used in the context of home research by Ali [81] who successfully tested this strategy in interviews and focus group discussions about the meanings of family and home. In this study, photo-elicitation interviews were used only to investigate the phenomenon of building a home in Australia and only when the family was willing to share their photographs with the researcher without any imposition or insistence on the researcher’s part. Photo-elicitation interviews can be realized with three different kind of photographs: subject-produced, researcher created or pre-existing images. The researchers used pre-existing photographs from the photo albums of the respondents which were personally selected by the informants who agreed to share them with the researchers. Another important point in photo elicitation interviews is the fact that during these interviews the questions posed to the participants were deliberately vague. The spontaneity of these vague queries helped to reduce the rigidity of the interviewer-interviewee situation and, at the same time, led to uncovering themes that were not triggered by the open-ended interviews.

Focus group discussions

Since the 1980s, across different fields of social, cultural and policy research, there has been increasing interest in the use of focus group discussions [82]. This method involves a good degree of interaction between informants on the topic under investigation, offering the advantage of generating data that would not have emerged in interviews. Therefore, to supplement and complete the open-ended interviews and the photoelicitation interviews, focus groups were used. The participants of the focus group discussions were the same people involved in the interviews conducted in Australia-the ten Veneto migrant families who settled in Brisbane. These participants consider themselves to be friends. This has overcome the problem of ‘breaking the ice’ at the beginning of the focus group discussion and has assured a climate of mutual trust between members, which, in turn, has facilitated the flow of conversation and interaction between them. To have a certain amount of control over the discussion, the researchers have used topics as a guide, together with some fixed questions. Following, who suggested that in focus group discussion visual clues can be used, the researchers asked the respondents to bring photographs related to the topic and that were important to them. These photographs helped the participants to convey their message to the other members of the group more quickly and more effectively than could have been accomplished by words alone.

When combining this research method with other data collection strategies, the focus group discussion can be used at the beginning of the research process or at the end of it. Used focus groups at the start of her research as the main strategy, followed by some interviews. At the start, focus group discussion can help the researcher define the main study themes. When used at the end of the study it helps the researcher explore the findings that have emerged from other methods of data collection. For this study, the researchers used the focus group at the end, after the researchers had finished the analysis of interviews. In other words, the researchers utilized the focus group as a consultative means of validating my initial interpretation of data coming from the interviews, and to further clarify some concepts raised previously that needed amplification.

Image-based data: photographs and drawings

The secondary sources of data used in this study are based on visual material. All the urban disciplines use visual sources more or less explicitly whether through mapping, architectural rendering, photographic surveys, land use or building condition surveys. Especially in the fields of architecture and planning, visual materials boasts a long tradition and have always been important in documentation, research, presentation and teaching [83]. Today however, visual documentation is not exclusive to urban disciplines and is also used in other academic circles including anthropology, history and cultural geography. Prosser [80] informs us that over the last three decades “qualitative researchers have given serious thought to using images with words to enhance understanding of the human condition. They encompass a wide range of forms including film, photographs, drawings, cartoons, graffiti, maps, diagrams, signs and symbols” (p.1). Particularly relevant is the example of the visual sociologist, who in his research on migrant ethnic neighborhoods in New York predominantly used photographs. Also in the current research the researchers made use of visual material in the form of photographs and graphic drawings related to the phenomenon of building a house in Australia. This material was in the possession of the Veneto migrants and was collected during the photo-elicitation interviews. The photographs of the participants fall under the definition of ‘found images’, that is photographs produced for reasons not directly connected with the research. Since the found images belong to the participants it was necessary for the researchers to obtain their permission to use their visual material in the current research. This first set of material has been supplemented by photographs of the houses belonging to the participants in Brisbane and in the Veneto region and taken by the researcher at the time of the interviews, after obtaining permission from the informants. The camera used is a Pentax MG with a 50mm lens. The researchers should note that my photographs attempt to be as close as the researchers could get to what an ordinary person might see as he/she looks at the domestic space. They are not attempts at artistic representations but are intended to document the domestic scene. These images were created and owned by the researcher, therefore there were no problems related to seeking permission for the use of this material.

Data recording and transcription

The first set of interviews was conducted with the ten Veneto migrant couples and took place in Brisbane between January 2011 and September 2011. Every migrant family was interviewed three times (for three topics) and every interview lasted one hour. The second set of interviews was conducted among the five Veneto families and took place in Italy in October 2011. These families were interviewed twice on the topic of building a home in the Veneto region. All interviews-semistructured interviews, photo elicitation interviews, for the first set of informants and only semi-structured interviews for the second set of informants - were conducted in the homes of the participants, at their invitation. This solution was the most convenient for them and it also provided a relaxed space to talk undisturbed. Two focus group discussions with the Veneto migrant families took place at the Italo-Australian Club in New market, Brisbane, at the end of the interviewing process in November 2011. Here the participation of the subjects was constant, with all the interviewed couples being punctual and joining the appointments.

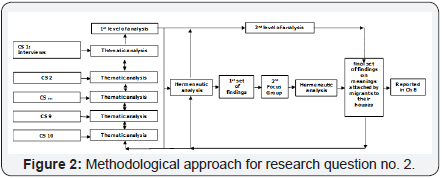

Data analysis procedures: Analysis of qualitative data is an inductive open-ended interpretive process. Accordingly, to analyse and interpret the data from this research, the researchers have used two forms of data analysis: conventional analysis; and a modified form of hermeneutic analysis explained in succession below.

First level of analysis: In this first phase of analysis of the data originated from the interviews, photo-elicitation interviews, focus group discussion and documents, the researchers have used ‘conventional analysis’ to identify broad themes through coding. These data have been purposefully sorted into meaningful master categories, grouping things that were similar. This new organization of data needed a second level of interpretation which was carried out using hermeneutic analysis.

Second level of analysis hermeneutics: To gain a deeper understanding of the themes originating from the first level of analysis and to facilitate the relationships between themes, the researchers used hermeneutic analysis. Argues that concepts associated with place and migrant people are complex to extrapolate and often have different layers, requiring skilled interpretation. Thus, she used hermeneutic analysis. The way Armstrong utilised hermeneutic phenomenology in her analysis provides insight for my study, since similarly to her, the researchers also used a form of phenomenological interpretation based on the philosopher Madison [85] as explained below. Hermeneutics (from the Greek Ερμηνεύς, ‘interpreter’) is the study of interpretation and initially was closely linked to the interpretation of the Bible and related texts of the Christian tradition. More recently, the term is used in a broader sense to denote the study of theories and methods involved in the interpretation of all kinds of texts, the concept of ‘text’ here being extended beyond merely written documents to include any number of objects (e.g. film, art, society, etc.) that may be subjected to interpretation.

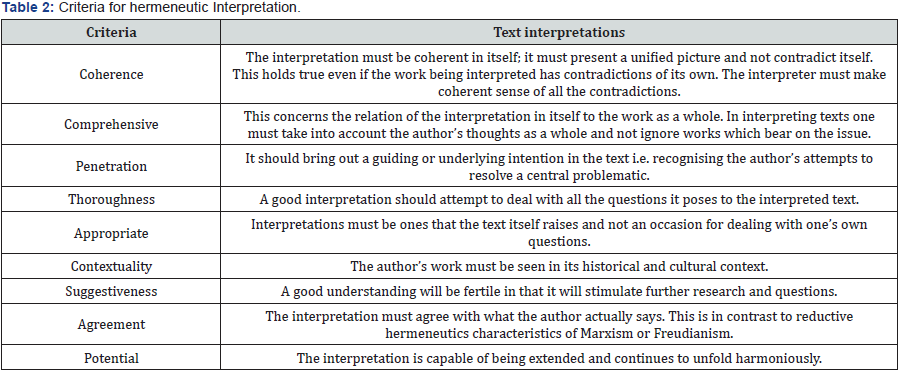

In the 1970s discussion occur around positivistic hermeneutics versus philosophic hermeneutics. Positivistic hermeneutic, with its clearly developed set of rules for the interpretation of biblical scripts, has also been employed by many cultural geographers whose interpretations about places and their value derives from objective rig our and mapping. In philosophical studies, this positivist position is argued by Hirsh [86] who sets out a science of interpretation. This is in opposition to phenomenological hermeneutics theories of the philosopher Gadamer [87]. Gadamer takes an anti-methodological position and argues that hermeneutics is not a science but an art of interpretation. A position in between the extremes of Hirsh’s positivist hermeneutics and Gadamer’s anti-methodological standing is advanced by the philosopher. As argues, a satisfactory theory of hermeneutic should include criteria for the work of interpretation. This ensures that interpretations are not easily taken or are gratuitous; instead, criteria facilitate rational judgments based on persuasive arguments stresses that these criteria are an articulation of what generally occur in practice. Such criteria are summarized in the following Table 2.

Validation

Validation is an important part of qualitative studies and is concerned with cross-checking the evidence collected and its interpretation to assure accuracy and credibility of the findings. The researchers have employed three strategies to check the accuracy and credibility of my findings. The researchers have adopted methodological triangulation during the data collection phase, while in the analysis phase the researchers have used of internal validation from respondents and external validation from colleagues.

Triangulation is a metaphor derived from trigonometry, surveying and navigation to indicate the convergence of two or more viewpoints on a single position. When utilised by social scientists, triangulation involves testing whether data collected with one method are repeated by other methods [96]. The principle behind triangulation is that if similar methods produce the same results, it would seem reasonable to conclude that the data are accurate. In this research triangulation has been applied in the data collection by using: interviews, photoelicitation interviews, focus group discussions and collection of photographs and drawings. Viewing the various topics under investigation from these four different perspectives has allowed a better understanding of the various phenomena under investigation and more importantly for this discussion, has assured their accuracy and credibility [97].

Reporting the findings

The role of ethnographic and phenomenological researchers is to describe the phenomenon under study as faithfully to the original as possible, uncovering the essence and the complexity of the situation investigated. This has to be done by bringing the reader as close as possible to the experiences of the phenomenon under investigation, that is “to see the thing through the eyes of others” and “to provide a description of matters that adequately portrays how the group in question experiences the situation”. The description therefore must be fairly detailed and must include aspects of the experience that appear to be contradictory, irrational or bizarre. However, [98] points out that traditional phenomenological description might create boredom in the reader and suggests that descriptions of a phenomenon can be enriched by the production of ‘living texts’. Living texts can utilize fiction, metaphors, poetry, graphic (drawings, printmaking) and visual arts (painting, photography, filmmaking) “to create a portrayal which carries the immediacy and impact of an experience” (p. 8).

Metaphors are repositories of important meanings and have been commonly used in applied hermeneutics. Argues for the use of metaphors in reports on migrants and places, since migrant texts are laden with them as people use them to explain their life experiences [99]. Therefore, incorporating metaphors in the text draws the reader closer to the experience lived by the informants of the study.

At the same time, this study has used also drawings and photographs to intensify the experience of the reader [100]. Warns that certain disciplines may find this more innovative and creative approach problematic. For this research, this is not the case since in human geography, as well as in architecture and visual sociology, it is common practice to include graphic drawings and photographs in the report, and cultural geographic publications are rich in pictorial format (handmade drawings, architectural drawings, photographs and even paintings and prints) that intermingle with the written texts to which they make reference Figure 1 & 2.

Findings

Q 1: How have the Italians from the Veneto region built their houses in Brisbane?

The findings reveal that there is a specific sequence of four events relating the experience of migration of the subjects of this study to the construction of their houses in Brisbane. The sequence, common to all the families interviewed in this study, is organized around the chronology of their migration experience and includes:

I. The decision taken in the 1950s of leaving the native country.

II. The liminal plan thought for the first years in Australia and the modifications brought to it in the successive years of the 1960s.

III. How this impacted on the way in which the respondents solved the issue of accommodation chosen in Australia from the 1960s to the 1980s.

IV. The decision taken in the 1980s to settle permanently in Australia. This sequence, mediated by the culture of family migration of the respondents and by their Italian mentality, resulted in these migrants building their homes in Brisbane in the 1980s and early 1990s.

This study shows that these dwellings were planned and built by the migrants themselves. The latter have actively participated in the design of their homes, relying on a builder only to resolve the bureaucratic framework. Equally, the Italian migrants were very much involved in the construction of their homes with the assistance of relatives, “paesani”, and Italian friends, following their areas of expertise in the building industry. This participation in the process of planning and building their home demonstrates the vernacular nature of these houses. Since these dwellings have been constructed by migrants and in a migrant context, this study argues that they be labeled ‘migrants’ vernacular dwellings’, a definition never previously used

This study demonstrates that these domestic dwellings were planned and built by the Italian migrants by taking as reference the architectonic culture of their land of origin. Through the study of the facades and the internal and external settings of the houses in Brisbane, this research has shown a strong persistence of form of two models (ideals) belonging to the architectonic culture of the land of origin (rural domestic houses and Palladian villas in the Veneto region). This has been demonstrated by the study of Italian and Veneto architectonic customs and traditions (accepted way of doing things) maintained in the domestic dwellings in Brisbane. These models, customs and traditions have been considered important by the migrant families in this study, who have imported them to Australia and transplanted them in their homes in Brisbane.

The presence of the culture of the land of origin is also confirmed through the study of activities (socialising, cooking and tending the garden) performed in three internal and external settings of the houses in Brisbane (double living areas, two kitchens and the garden). These activities are translocated from the land of origin, therefore the settings, congruent with these activities, are expression of that particular culture. In other words, this study shows that the Veneto migrants planned and built their homes in Brisbane, driven by the cultural force of the country of origin. This has been supported by economic forces, which have made possible the construction of these houses.

The peculiarity of these domestic dwellings in their internal spaces, external spaces and facades, has permitted the construction of a new typology of migrants’ house specifically for the Veneto migrants in Brisbane for the period between the 1980s and the early 1990s. Contributing to Brisbane’s cultural landscape and considering the value for the Italian community and for the Australian mainstream who prize the complexity of their historic heritage, these houses now raise the possibility of historic protection of at least one dwelling of this style.

Q2: What are the meanings that the Veneto migrants have attached to their houses in Brisbane?

The study shows that the domestic dwellings in Brisbane have deep significance for this migrant group, and that they are laden with many meanings. They include:

- Sistemazione in Australia.

- Hard work undertaken in Australia.

- Pride in their Italian culture.

- A point of reference for the maintenance of family unity.

- A feeling of security.

This research shows that the migrant’s culture of the country of origin is not limited to the physical fabric of the domestic dwellings but is also present in the symbolism associated with them. As this study demonstrates, the five meanings listed above are both directly and indirectly embedded in the culture of the country of origin. This means that among the many variables determining these meanings, the cultural one is the most pivotal.

An intrinsic aspect of the overarching question is where is home located for this group of migrants. ‘Home’ has been recognized to be ‘here’ and ‘there’, where here is the domestic dwelling in Brisbane and there is the hometown in Italy. Therefore, as a result for this group of migrants, the concept of home resulted to be multi-scalar and pluri-local. This also means that the houses in Brisbane can be really called ‘home’.

Reflection on methodology

The two concerns of this study consist in the exploration of the phenomena of building a house in the host county, incorporating the phenomenon of migrating from the sending to the receiving country (Research Question 1), and the meaning associated with the homes build in the host country (Research Question 2). The exploration of the phenomena of building a house in the host county began with the analysis of the migration experiences lived by a group of Italian migrants originally from the Veneto region who migrated to Australia after the Second World War (1950s).

These experiences contributed to the construction of their homes in Brisbane, in the 1980s and 1990s. This exploration progressed with the analysis of the material realm of these homes, and concluded with an analysis of the various meanings the subjects have attached to their homes. Even though the main focus of the research relates to material objects (the domestic dwellings in Brisbane), this study has made strong use of the intervention of human subjects - the migrants living in Australia, together with their relatives and friends living in Italy. This research used accepted methods of qualitative research: interviews; photo-elicitation interviews conducted both in Australia and in Italy; and focus group discussions conducted in Australia. The methods used in this study include the collection of visual material in the form of photographs and drawings related to home possessed by the informants and complemented by photographs taken by the researcher. After conventional content analysis, which consisted of codifying the transcriptions generated from the first three methods into meaningful themes, a deeper level of analysis has taken place using phenomenological hermeneutics.

Hermeneutics is most commonly utilised for the interpretation of complex texts of biblical studies, however, it has been also effectively applied in texts related to migrant research in cultural geography. Therefore, following [101], the interpretations in this research have been based on hermeneutic principles requiring the interpretations to be coherent, comprehensive and thorough. They also had to be penetrating, contextual and appropriate while simultaneously having the potential for further levels of interpretation. These have then provided to the Italian respondents to this study to seek their validity, and later to qualitative colleagues to seek external validation. This process of analysis has determined the final interpretations of the domestic dwellings belonging to Veneto migrants who have settled in Brisbane. With these kinds of procedures, the interpretation of the cultural and symbolic elements of the migrant domestic dwellings expressed throughout this research are not facile whims but are derived from a rigorous process which has assured that the interpretations reached are rigorous and satisfactorily deep.

The current study, then, reinforces the efficacy and validity of this interpretative practice. Reflecting on the cooperation of the participants in the interviewing process and focus group discussions, at the same time the current study reveals the richness of knowledge regarding the homes, held by the migrants who are the proprietors, users, designers and builders. Therefore, the study recognizes the value of people-centered forms of research methods, and suggests that investigations of migrant places in a cultural landscape are not limited to the analysis of the physical fabric completed by the researcher, but can also be successfully investigated through qualitative methods involving the participation of human subjects.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank the interviewed first generation Italian migrants for their time and availability. In order to understand their life experiences, participants were interviewed multiple times and, although it was anticipated that in-depth interviews were supposed to last for approximately one hour each, most exceeded this limit. With great enthusiasm, they all wanted to tell their own unique story. Also, the authors express their gratitude to the anonymous reviewers for their comments, which contributed to an improvement of this paper.

References

- Jordens A (1995) Redefining Australians. Sydney: Hale and Iremonger.

- Jupp J (1996) Understanding Australian Multiculturalism. AGPS, Canberra, Australia.

- Murphy (1993) The Other Australia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, India.

- Cresciani G (1985) The Italians. Macarthur Press, Parramatta Sydney, Australia.

- Cresciani G (1988) Migrants or Mates. Italian Life in Australia. Knockmore Enterprises, Sydney, Australia.

- Cresciani G (2003) The Italians in Australia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, India.

- Furlan R (2015b) History of Italian Immigrants Experience with Housing in Post WWII Australia. International Journal of Arts 5(1): 8-20.

- Furlan R (2015c) The Spatial Form of Houses Built by Italian Migrants in post WWII Brisbane, Australia. Architecture Research 5(2): 31-51.

- Pesman R, Kevin C (1998) A History of Italian Settlement in New South Wales. Ethnic Communities Consultation Program.

- Baldassar L (2005) Italians in Australia. M Ember, CR Ember, & I Skoggard (Eds.), Encyclopedia of Diasporas: Immigrant and Refugee Cultures around the World New York, Springer.

- Church J (2005) Per l’ Australia: The Story of Italian Migration. Carlton (Ed.), Melbourne University publishing, Australia.

- Pascoe R (1987) Buongiorno Australia: Our Italian Heritage. Richmond, Victoria, Australia: Greenhouse Publications, USA.

- Laura F, Finch L (2008) The Italian Restaurant Scene in Brisbane in the 1930s. Paper presented at the 9th Australasian Urban History/ Planning History Conference: Sea change: New and Renewed Urban Landscapes, University of the Sunshine Coast, Queensland, Australia.

- Sagazio C (2004) A Lasting Impact: The Italians. A History. P Yule & Carlton (Eds.), Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 73-92.

- Baldassar L, Pesman R (2005) From Paesani to Global Italians: Veneto Migrants in Australia. Perth: UWA Press, Australia.

- Castles S (1992) Italian Migration and Settlement since 1945 Australia’s Italians: Culture and Community in Changing Society. Allen & Unwin (Eds.), Sydney, Australia.

- Castles S, Alcorso C, Rando G, Vasta G (1992) Australia’s Italians: Culture and Community in a Changing Society. Allen & Unwin (Eds.), Sydney, Australia.

- Panucci F, Kelly B, Castles S (1992) Italians Help Build Australia. S Castles, C Alcorso, G Rando & E Vasta (Eds.), Australia’s Italians, Culture and Community in a Changing Society, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, Australia.

- Randazzo N, Cigler M (1987) The Italians in Australia. AE Press, Melbourne, Australia.

- Faggion L, Furlan R (2017) Cultural Meanings Embedded in the Façade of Italian Migrants’ Houses in Brisbane, Australia. International Journal of Architectural Research-Archnet-IJAR 11(1): 119-137.

- Furlan R (2015a) Cultural Traditions and Architectural Form of Italian Transnational Houses in Australia. Archnet-IJAR, International Journal of Architectural Research 9(2): 45-64.

- Furlan R, Faggion L (2016) Built Form and Culture: Italian Transnational Houses in Australia. Arts Social Sci J 4(5): 7:178.

- Furlan R, Faggion L (2015) Italo-Australian Transnational Houses: Critical Review of a Qualitative Research Study. American Journal of Sociological Research 5(3): 63-72.

- Furlan R, Faggion L (2015) Italo-Australian Transnational Houses: Culture and Built Heritage as a Tool for Cultural Continuity. Architecture Research 5(2): 67-87.

- Furlan R, Faggion L (2016) Italo-Australian Transnational Houses: Built forms enhancing Social Capital. Archnet-IJAR, International Journal of Architectural Research 10(1): 27-41.

- Creswell JW (2003) Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative and Mixed Methods Approaches (2nd Edn.), Sage Publications, California, United States.

- Crotty M (1998) The Foundation of Social Research: Meaning and Perspective in the Research Process. Sage Publications, London, UK.

- Grbich C (2007) Qualitative Data Analysis: An Introduction. London, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, New Delhi, India.

- Seale C (2004b) History of Qualitative Methods. C Seale (Ed.), Researching Society and Culture (2nd Edn.), Thousand Oaks, Sage Publication, London, pp. 99-113.

- Armstrong H (2000) Cultural Pluralism within Cultural Heritage. Migrant Place Making in Australia. University of New South Wales, Australia.

- Armstrong H (2003b) Interpreting Landscapes/Places/Architecture: The Place for Hermeneutics in Design Theory and Practice. Architectural Theory Review 8(1): 63-79.

- Armstrong H (2004) Making the Unfamiliar Familiar: Research Journeys towards Understanding Migration and Place. Landscape Research 29(3): 237-260.

- Thompson S (1994) Suburbs of Opportunity: the power of home for migrant women. K Gibson & S Watson (Eds.), Metropolis Now planning and the urban in contemporary Australia, Pluto Press, Sydney, Australia, pp. 33-45.

- Armstrong H (1994) Cultural Continuity in Multicultural Sub/Urban Places. Gibson K & Watson S (Eds.), Metropolis Now: Planning and the Urban in Contemporary Australia. Leichardt, Pluto Press, NSW, Australia.

- Thompson S (1996) Womens’ Stories of Home: Meaning of Home for Ethnic Women Living in Migrant Communities. University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia.

- Denscombe M (2007) The Good Research Guide for Small-Scale Social Research Projects (3rd Edn.), Open University Press, Berkshire, England, UK.

- Malinowski B (1922) Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guineam, Routledge & Kegal Paul (Eds.), London, UK.

- Malinowski B (1929) The Sexual Life of Savages. Routledge & Kegan Paul (Eds.), London, UK.

- Mead M (1942 [1930]) Growing up in New Guinea: a Study of adolescence and sex in primitive societies. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books p.272.

- Seale C (2004a) Coding and Analysing Data. C. Seale (Ed.), Researching Society and Culture (2nd Edn.), London, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications. New Delhi, India, pp. 305-323.

- Walsh D (2004) Doing Ethnography. C. Seale (Ed.), Researching Society and Culture (2nd Edn.), London, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, New Delhi, India, pp. 225-237.

- Whyte WF (1993/1943) Street Corner Society: The Social Structure of an Italian Slum, Universty of Chicago Press, Chicago, USA.

- Kitchin R, Tate NJ (2000) Conducting Research into Human Geography: Theory, Methodology and Practice. Essex, Prentice Hall, USA.

- Buttimer A (1976) Grasping the Dynamism of Life world. Annals of the association of American Geographers 66(2): 277-292.

- Buttimer A (1976) Grasping the Dynamism of Life world. Annals of the association of American Geographers 66(2): 277-292.

- Tuan Y (1974) Topophilia: A Study of Environmental Perception, attitudes and values. Englewood Cliffs, USA, NJ, Prentice Hall.

- Tuan Y (1977) Space and Place: The Perspective of Experience. University of Minnesota Press, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA.

- Relph E (1976) Place and Placelessness. Pion, London, UK.

- Relph E (1981) Phenomenology. ME Harvey & BP Holly (Eds.), Themes in Geographic Thought, Croom Helm, London, UK, pp. 99-114.

- Seamon D (1979) A Geography of the Lifeworld: movement, rest and encounter. Croom Helm, London p. 227.

- Seamon D (2011) Place, Place Identity and Phenomenology: A Triadic Interpretation based on JG Bennett’s Systematics, H Casakin, O Romice, & S Porta (Eds.), the Role of Place Identity in the Perception, Understanding and Design of the Built Environment. Betham Science Publisher, London.

- Willis P (2004) From ‘The Things Themselves’ to a ‘Feeling of Understanding’: Finding Different Voices in Phenomenological Research. The Indo-Pacific Journal of Phenomenology 4(1): 1-13.

- Pile S (1993) Human Agency and Human Geography Revisited: A Critique of New Models of the Self. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 18(1): 122-139.

- Speigelberg H (1959) The Phenomenological Movement: A Historical Introduction. Martinus Nijhoff (Ed.), Boston, Massachusetts, USA.

- Dovey K (1985) Home and Homelessness. I Altman & CM Werner (Eds.), Home Environments, Plenum Press, New York pp. 33-61.

- Thomas J (2006) Phenomenology and Material Culture. C Tilley, W Keane, S Kűchler, M Rowlands, & P Spyer (Eds.) Handbook of Material Culture. Sage Publications, London pp. 43-59.

- Speigelberg H (1975) Doing Phenomenology: Essays on and in Phenomenology. Martinus Nijhoff (Ed.), The Hague, Europe.

- Valle R, Halling S (1989) Existential-Phenomenological Perspectives in Psychology. Plenum Press, New York, USA.

- Cloke P, Philo C, Sadler D (1992) Approaching Human Geography: An Introduction to Contemporary Theoretical Debates. Paul Chapman, London, UK.

- Armstrong H (2003a) Conceptual Journeys: Using Qualitative Processes. An Inter-Cultural Exploration of Place. Paper presented at the Association of Qualitative Researchers Conference, Creating Spaces of Awareness, Sydney, Australia.

- Thompson SM, Barrett PA (1997) Summary Oral Reflective Analysis: a method for interview data analysis in feminist qualitative research. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 20(2): 55-65.

- Stake RE (1995) The Art of Case Study Research. Thousand Oaks, Sage Publications, California, USA, pp. 49-68.

- Zeisel J (1984) Inquiry by Design: Tools for Environment-Behaviour Research: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, India.

- Yin RK (2003) Case Study Research: Design and Methods (3rd Ed.). Thousand Oaks London, Sage Publications, New Delhi, India.

- Baldassar L, Pesman R (2005) From Paesani to Global Italians. Veneto Migrants in Australia. Western Australia, University of Western Australia, Australia.

- Krase J (2006) Seeing Ethnic Succession in Little Italy: Change Despite Resistance. Modern Italy 11(1): 79-95.

- Mecca L, Iozzi L (2000) Our Story our Heritage: the Italian Australian Experience in the Collection of the Italian Historical Society. P Genovesi, W Musolino, IM O’Brien, M Pallotta-Chiarolli & M Genovesi (Eds.), In Search of the Italian Australian into the New Millennium, Conference Proceedings. Thornbury, Gro-Set, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 77-93.

- Price CA (1963) The Method of Statistics of Southern Europeans in Australia. Oxford University Press, Melbourne, Australia.

- Moholy-Nagy S (1957) Native Genius in Anonymous Architecture. Horizon Press, New York, USA.

- Alexander C (1964) Notes on the Synthesis of Form, Cambridge, MA, Harvard University Press.

- Rudofsky B (2003 [1964]) Architecture without Architects: A Short Introduction to Non-Pedigreed Architecture. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, New Mexico, US.

- Glassie H (2000) Vernacular Architecture: Material of Culture. Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana University Press, USA, pp. 1-21.

- Oliver P (2007) Shelter and Society: Vernacular Architecture in its Cultural Contexts. Paper presented at the General Studies Lectures: Engineering towards Development and Change, University of Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

- Klaufus C (2005) Bad Taste in Architecture. Discussion of the Popular in Residential Architecture in Southern Ecuador. Paper presented at the Doing, Thinking, Feeling Home: the Mental Geography of Residential Environment, Netherlands, Europe.

- ABS (2004) 2001 Census of Population and Housing, Cat. no. 3105.0.65.001 Australian Historical Population Statistics, TABLE 86. Population, Sex, Country of Birth, States and Territories.

- Huber R (1977) From Pasta to Pavlova. A Comparative Study of Italians in Sydney and Griffith, St Lucia, Brisbane, University of Queensland Press, Australia.

- Byrne B (2004) Qualitative Interviewing. C Seale (Ed.), Researching Society and Culture (2nd Edition.), London, Thousand Oaks, Sage Publication, New Delhi, India, pp. 179-192.

- Patton M (1990) Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods (2nd Ed.), Newbury Park, Sage Publications, California, USA.

- Warren CAB, Karner TX (2005) Discovering Qualitative Methods: Field Research, Interviews and Analysis. Roxbury Publishing Company, California, USA.

- Prosser J, Schwartz D (1998) Photographs within Sociological Research Process. J Prosser (Ed.), Image Based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers, Falmer Press, London, UK, pp. 115-129.

- Ali S (2003) Mixed-race Post-race: gender, new ethnicities and cultural practices. Berg, London & New York.

- Tonkiss F (2004) Using Focus Group. C Seale (Ed.), Researching Society and Culture (2nd Ed.), London, Thousand Oak, Sage Publication, New Delhi, India pp. 193-206.

- Krase J, Hutchinson R (2005) Research in Urban Sociology: Race and Ethnicity in New York City. JAI Press, Boston, Massachusetts, USA, (Vol 7) pp. 25-55.

- Prosser J (1998) Image-Based Research: A Sourcebook for Qualitative Researchers. Falmer Press, London, UK.

- Madison GB (1988) The Hermeneutics of Post modernity: Figures and Themes. Bloomington, Indiana University Press, USA.

- Hirsh ED (1967) Validity in Interpretation. New Haven, Conn, Yale University Press, United States.

- Gadamer HG (1976) Philosophical Hermeneutics. Berkeley, University of California Press, United States.

- Bourdier JP, Alsayyad N (1989) Dwellings, Settlements and Traditions: Cross-Cultural Perspectives. Berkeley, Lanham, London, University Press of America, United States.

- Faggion L, Furlan R (2016) Post-WWII Italian Migration from Veneto (Italy) to Australia and Transnational Houses in Queensland. International Journal of Arts 6(1): 1-10.

- Fez-Barringten B (2012) Architecture: The Making of Metaphors. Cambridge Scholars Publishing, England, UK.

- Furlan R, Faggion L (2016) Post-WWII Italian Immigration to Australia: The Catholic Church as a Means of Social Integration and Italian Associations as a Way of Preserving Italian Culture. Architectural Research 6(1): 27-41.

- Itcaina X (2006) The Roman Catholic Church and the Immigration Issue. American Behavioral Scientist 49(11): 1471-1488.

- Mertens DM (1998) Research Methods in Education and Psychology: Integrating Diversity in Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, India.

- Miller-Lane B (2007) Housing and Dwelling: Perspectives on Modern Domestic Architecture. Routledge, London, UK.

- Noble AG (2007) Traditional Buildings: A Global Survey of Structural Forms and Cultural Function (International Library of Human Geography). IB Tauris Publishers, London, UK.

- Oliver P (1997) Encyclopedia of the Vernacular Architecture of the World. Cambridge University Press, England, UK, (3 Volumes).

- Oliver P (2003) Dwellings: the Vernacular House World Wide. Phaidon Press, London, UK.

- Preston-Blier S (2006) Vernacular Architecture. C Tilley, W Keane, S Küchler, M Rowlands, & P Spyer (Eds.), Handbook of Material Culture, London, Thousend Oaks, Sage Publications, New Delhi, India, pp. 230- 253.

- Rapoport A (1988) Spontaneous Settlements as Vernacular Design. C Patton (Ed.), Spontaneous Shelter: International Perspectives and Prospects, Temple University Press, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, USA, pp. 51-77.

- Sagazio C (2004) Carlton, A History. P Yule (Ed.), a Lasting Impact: The Italians, Melbourne University Press, Melbourne, Australia, pp. 73-92.

- Tuan Y (1976) Humanistic Geography. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 66(2): 266-276.