Anthocyanins in Leaves, Fruits and Flowers. An Investment that Makes Sense

Jana Matejickova1* and Jiri Patocka2,3

1Department of Sustainable Development, Grinity s.r.o., Prague, Czech Republic

2Faculty of Health and Social Studies, University of South Bohemia České Budějovice, Czech Republic

3Department of Chemistry, Faculty of Science, University of Hradec Králové, Czech Republic

Submission: September 11, 2024; Published: September 25, 2024

*Corresponding author: Jana Matejickova, Department of Sustainable Development, Grinity s.r.o., Prague, Czech Republic

How to cite this article: Jana Matejickova* and Jiri Patocka. Anthocyanins in Leaves, Fruits and Flowers. An Investment that Makes Sense. Ecol Conserv Sci. 2024; 4(4): 555642. DOI:10.19080/ECOA.2024.04.555642

Abstract

Anthocyanins offer overall, versatile and effective protection to plants under stress. Under conditions of high environmental stress, anthocyanins may play a key role in plant survival. This refers in particular to anthocyanins present with the leafy parts of the plant. In addition, anthocyanins present in the petals play a key role in the plant’s visual communication with its pollinators. Beyond the normal visual attraction required to attract pollinators, some plants have evolved the ability to exploit the ability of anthocyanins to change colour depending on pH so that they can tailor their communication with pollinators to their actual needs. Petal attractiveness is also an important economic parameter in ornamental plant species and therefore people are also trying to discover the possibilities and functions of anthocyanins in flowers. Hydrangea is the best-known example. In addition, anthocyanins are widely used not only in the food dye industry but also in food safety control, where use has also been found for their ability to change colour upon pH change.

Keywords: Plant Pigments; Petal Colour Change; Anthocyanins; Delphinidin-3-Glucoside

Introduction

A wide variety of different dyes are found in plants. They are divided into hydro chromes (water-soluble dyes) and lipochromes (fat-soluble dyes). Hydro chromes are found in the cell sap of vacuoles, lipochromes are found in plastids. Lipochromes include e.g. chlorophylls, β-carotene, etc. Hydro chromes include anthocyanins and flavones. Flavones are oxidation products of anthocyanins and are yellow in colour [1].

Anthocyanins, which are formed by biochemical reduction of flavonoids, have blue, purple, pink or red coloration [2]. Anthocyanin dyes are highly reactive and very volatile. The colour and stability is mostly influenced by the structure of the molecule, the action of enzymes, the pH of the environment, temperature, or the action of oxygen or radiation. Anthocyanins lose their colour by hydrolysis of the glycosidic bond.

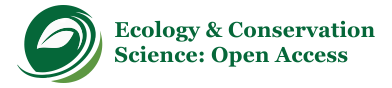

In general, they turn pink or red in acidic environments and blue or greenish in basic environments. Thus, they function as natural acid-base indicators [2] (Table 1) (Figure 1).

Red cabbage extract contains a large amount of anthocyanins, so it is a good example to illustrate the colour shifts depending on pH change (Figure 2). Naturally occurring anthocyanins are hetero glycosides that consist of both a sugar component and an aglycone (non-sugar component) = anthocyanidin.

There are 500 known different anthocyanins and 28 anthocyanidins, of which only six are most abundant in vascular plants. These are pelargonidin (red), cyanidin (purple) peonidin (purple), delphinidin (purple blue), petunidin (purple-blue) and malvidin (purple). Of these six, cyanidin, pelargonidin and delphinidin occur in the largest proportion. They are 80% in the leaves, 69% in the fruit and 50% in the flowers [5]. In fruit fruits, anthocyanins are formed in the so-called climacteric phase probably by dehydrogenation of proanthocyanins (leucoanthocyanins), which belong to the fruit tannins. Individual tissues form anthocyanins unequally. In some plant species the dyes are contained in the whole fruit, in others, for example, only in the skin [6]. We can see how the formation of anthocyanins is stimulated by the effect of sunlight in a red-coloured apple only on the sunlit side [1].

Anthocyanins have been talked about recently mainly due to their high antioxidant activity not only in connection with the colourful fruits but also the flowers, which thus represent a very healthy food source. The rich plant pigment in the flowers originally evolved to make the plant attractive and attract pollinators. However, it is also characterised by its high antioxidant activity, thanks to the presence of anthocyanins. Edible flowers have already been shown to be effective in fighting tumours, inflammation and mutagenic effects. Although the use of flowers seems to be a very promising source of food and their health benefits should not be neglected, care should be taken when choosing flowers for consumption, as some species contain substances that are not entirely suitable for our organism and in some cases may even be harmful to health [5].

Many anthocyanins are used in the pharmaceutical industry for their anti-inflammatory and anticarcinogenic properties. Certain pigments from the anthocyanin group have been shown to be effective against coronary heart disease or diabetes and obesity. They also have a positive effect on eyesight or signalling pathways in cells [7].

By changing the colour of the flowers, the plant communicates with pollinators

It is well known that floral colour and scent are qualities that attract pollinators. Pollinators show a natural preference for specific floral attributes that they associate with a flower that provides food sources such as nectar and pollen. In addition, in some cases, flowers change the colour of their blooms, allowing pollinators to avoid unrewarding and old flowers and select rewarding flowers. This reduces repeat visits to the same flower and increases the pollination efficiency. Thus, some plants have learned to take advantage of the ability of anthocyanins to change colour in response to pH. As the flower develops, the pH changes and so does the colour of the corolla. Examples of these are lungworts (Pulmonaria sp.), forget-me-nots (Myosotis sp.), common snakeweed (Echium vulgare) and spring pea (Lathyrus vernus) [8] (Figure 3).

For plants that have multiple flowers at once, this colour key is used to give pollinators a preference for young flowers based on colour. Leaving the older flowers on the plant then has the function of increasing the attractiveness of the plant to pollinators at a distance [8].

At least a small change in flower colour is a phenomenon observed in many species of cryptic plants. This phenomenon is estimated to occur in 74 families, representing 21% of all insectpollinated families. The phenomenon of flower colour change is taxonomically widespread, morphologically variable and physiologically diverse. It has evolved many times independently in cryptic plants and provides a remarkable example of functional convergence [9].

Ornamental plant petals colour change

Perhaps the best-known plant species that can change the colour of its inflorescences in response to pH is Hydrangea sp. Hydrangeas are a natural indicator of the pH of the soil in which the plant grows. The inflorescences are blue when the shrub is growing in acidic soil and pink when growing in neutral to alkaline soils. Thus, while the colour of hydrangea flowers reveals the pH of the soil, their distinguishing colours are opposite to those of anthocyanins (Figure 4).

Soil acidity is a necessary but not sufficient condition for colour change. Hydrangea colours also depend on the availability of aluminium ions (Al3+) in the soil. The role of aluminium has been known since the 1940s but has only entered mainstream horticultural literature in the last two decades or so, and the exact mechanism has only recently been defined. Aluminium ions are mobile in acidic soil because of the ready availability of other ions they can react with, which can be taken up into the hydrangea to the bloom where they interact with the normally red pigment. Whereas in neutral to alkaline soil, the ions combine with hydroxide ions (OH-) to form the immobile aluminium hydroxide, Al (OH)3 . As a result, both aluminium ions and acidic soil are needed for hydrangea flowers to turn blue (Figure 5).

Al3+ is mobile in acidic soil conditions and in response to its stimulus, hydrangea roots secrete citric acid (C6H8O7). As a result, a solution of citrate ions (C6H5O7 3-) and citric acid forms around the roots in relative concentrations that are specific to the soil pH. The Al3+ then forms a stable complex with the citrate ions which is absorbed into the hydrangea roots. The plant transports Al3+ as this citrate complex. Other Al3+ tolerant plants such as buckwheat and rye also secrete simple organic acids to detoxify aluminium [10].

The accumulation of aluminium ions in hydrangeas occurs not only in the flower petal but also in the leaves. Although hydrangea leaves have the same concentration of aluminium as the flower petals, the leaves do not contain pigments that react with the aluminium ions, so the accumulation of aluminium in the leaves does not affect their colour. The high aluminium content thus present in both the leaves and the floral petals has no toxic effect on the plant. Hydrangeas are therefore classified as plants resistant to high aluminium content. The best soil additive for blueing is for example aluminium sulphate, Al2(SO4)3. On the other hand, if the purpose is to change a blue-flowering hydrangea into a red-flowering one, adding lime (or calcium hydroxide, Ca(OH2)) will produce an alkaline soil and the desired colour transition. However, such imposed changes from red to blue or from blue to red do not occur immediately; it often takes one or two growing seasons for shrubs in flower gardens to take on the desired colour. Growers of hydrangeas with blue flowers must water the potting medium regularly with aluminium sulphate to maintain the necessary levels to force the desired blue colour (but they cannot water too often or the excess Al3+ will kill the plant) [10].

From the above it can be seen that the pH of the soil is not directly responsible for the colour change in Hydrangea, but it is the aluminium ions and the internal pH of the cells remains constant for both red and blue petals. This is why its colouration differs in relation to the pH compared to the colour changes of anthocyanins and also why this phenomenon is so rare in nature. The other plant that has been shown to exhibit the same behaviour in petal colour changes as hydrangea is the Meconopsis betonicifolia [11].

Diverse functions of anthocyanins in plant leaves

As mentioned above, anthocyanins are also found in large quantities in the leaves. In the first place, anthocyanins are among the dyes involved in autumn leaf colouration. The amount of anthocyanins in leaves increases in autumn as flavones are reduced back to anthocyanins. In addition, chlorophyll is broken down, revealing other leaf colouring agents previously largely covered by chlorophyll [1]. The red colour caused by the accumulation of anthocyanins during autumn senescence is certainly related to protection against herbivore insects looking for suitable food plants for future larvae. Anthocyanins are not, however, the substance that directly deters insects, especially since a large number of herbivorous insects cannot recognise the red colour. Anthocyanins therefore act more as a camouflage for the green and yellow colours that are attractive to insects [12]. The increase in anthocyanins in autumn leaves may also be related to frost protection, as darker leaves absorb more heat [1].

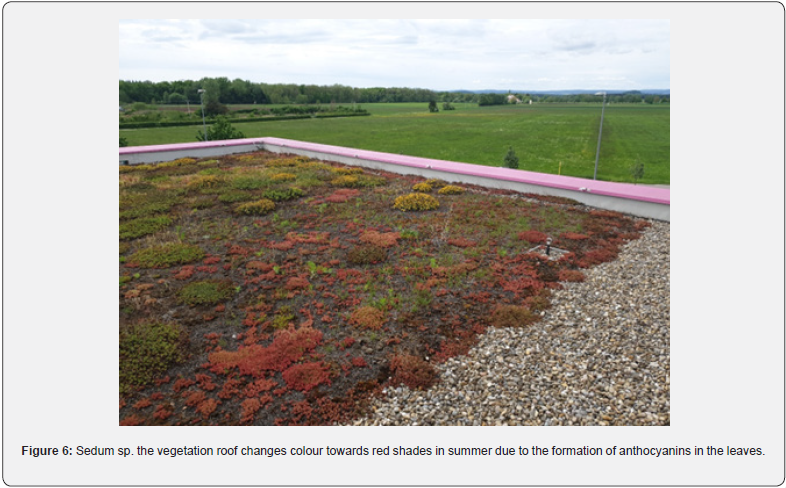

Anthocyanins in leaves also act as filters, protecting the photosystems in the leaves by absorbing radiation in the UV area of the electromagnetic spectrum. Therefore, anthocyanins protect leaves from stress caused by photoinhibitory light fluxes by absorbing excess photons that would otherwise be trapped by chlorophyll. Plants can therefore adapt to changes in solar radiation intensity by synthesising these pigments. Already in the 1990s, many experiments were conducted which showed that plants artificially exposed to UV-B radiation synthesized anthocyanins in response to excessive radiation [12]. Increased synthesis of anthocyanins was observed mainly in the upper structures of the leaf - in the epidermis cells, where anthocyanins were stored in the waxy layer of the adaxial side of the leaf, and in the leaf trichomes [13]. The results on irradiation of experimental plants that were defective in flavonoid synthesis, hence anthocyanins, showed that only 10% of the DNA remained intact in the tissue. In contrast, the anthocyanin-containing tissues were significantly more resistant to UV irradiation, with 54% intact DNA, and in addition, a longer irradiation time was required for DNA damage to occur at all [13]. This effect is often seen in plants at times when they are under drought stress. Loss of green color in plants is often observed in vegetative roofs of Sedum species, which cease to be green in summer (Figure 6).

However, studies show that anthocyanin synthesis is not directly related to drought stress. Rather, the results suggest that anthocyanin synthesis occurs due to excessive radiation that affects plants along with drought [12]. This is because anthocyanins can serve to reduce the osmotic potential of cells in the leaves under drought stress. The resulting reduction in leaf water potential could help to increase water uptake and/ or reduce transpiration losses. In combination with other antistress activities attributed to anthocyanins, this phenomenon may allow anthocyanin-containing leaves to tolerate suboptimal water levels. After the stress factors subside, the green colour of the leaves is restored. This transient nature of leaf anthocyanin accumulation may allow plants to respond quickly and temporarily to environmental variability rather than through more permanent anatomical or morphological modifications [14]. Anthocyanins are also excellent free radical scavengers. Purified solutions trap almost all reactive oxygen and nitrogen species. For this reason, this investment is worthwhile for plants, even assuming that the synthesis and vacuolar sequestration of anthocyanin molecules represents a significant metabolic investment for plant cells [15].

Applications in the food industry

The practical use of anthocyanins is probably best known in the food dye industry. They are typically extracted from sources such as purple corn, purple carrots, radishes, elderberries and other fruits and vegetables that are bred specifically for their high pigment concentrations [4]. Compared to other dyes, however, anthocyanins have their drawbacks. These include, in particular, their low colour stability and the consequent problems of storage and industrial processing. Obtaining pure preparations is also very expensive although waste materials such as peels or fruit pomace are usually used [5].

Synthetic dyes have a great advantage over natural ones in that they are stable and provide very rich colour. However, many manufacturers are now trying to refrain from colouring foods with synthetic dyes because of their proven adverse effects on the human body [5]. There are many rules and regulations regarding the colouring of food, and some foods are completely forbidden to have added colouring. These include baby food, honey, fruit juices and nectars. Only carotenes may be used to colour butter. Due to the technological and economic difficulty of isolating vegetable dyes from plant materials, nature-identical dyes, which are chemically the same substances as natural dyes but are produced synthetically, are used [3].

There is another very promising application for anthocyanins in the food industry that exploits their ability to change colour depending on pH. In intelligent packaging systems for fresh perishable foods, anthocyanin-based colorimetric indicators can be used to monitor the freshness or spoilage of food. Most perishable foods are highly susceptible to enzymatic/microbial spoilage and produce several volatile or non-volatile organic acids and nitrogenous compounds. As a result, the natural pH of fresh perishable foods changes significantly. The production of anthocyanin-based colorimetric indicators in smart packaging systems is an advanced technique that monitors the freshness or spoilage of perishable foods by displaying colour variations at different pH values [16].

Summary

Anthocyanins are arguably the most versatile of all pigments, and their diverse roles in plant stress responses result from both their physicochemical properties of light absorption and their unique combination of biochemical reactivities. Their photoprotective and antioxidant properties provide important survival aids to plants. But their benefits for plants does not end there. They bring increased leaf resistance to the effects of chilling and freezing, to contamination by metals such as aluminium and, not least, resistance to drought stress [15, 17,18]. Their use in a wide range of functions in the food industry is equally diverse.

References

- Colour reactions of anthocyanins, Teacher materials.

- Michalcova D, Plant colors and dyes, Institute of Botany and Zoology, Masaryk University Faculta of science, Brno.

- Podesvova V (2017) Plant dyes, Bachelor thesis, Brno.

- Why Do Anthocyanins Change Color, Givaudan Sense Colour learning center.

- Susankova K (2016) Chemical properties of anthocyanins useful for their proof and determination in food, Diploma thesis, Plzeň.

- Stavek J, Anthocyanins - red or blue-violet? Institute of Postharvest Technology of Horticultural Products, ZF Lednice, MZLU Brno.

- Santos BC (2014) Anthocyanins. Plant Pigments and Beyond. J Agric Food Chem 62: 6879-6884.

- Weiss M, Lamont B (1997) Floral color change and insect pollination: A dynamic relationship. Israel Journal of Plant Sciences 45: 185-199.

- Weiss M (1991) Floral colour changes as cues for pollinators. Nature 354: 227-229.

- Henry S (2014) Curious Chemistry Guides Hydrangea Colors, American Scientist 102(6): 444.

- Chenery EM (1946) Are Hydrangea flowers unique? Nature (Lond.) 158: 240-241.

- Nikodymova M, Anthocyanins in plant leaves: protective function and spectroscopic detection, Diploma thesis.

- Stapleton AE, Walbot V (1994) Flavonoids Can Protect Maize DNA from the Induction of Ultraviolet Radiation Damage. Plant Physiol 105: 881-889.

- Chalker SL (2022) Do anthocyanins function as osmoregulators in leaf tissues? In: Gould K.S, Lee D.W, editors. Anthocyanins in Leaves. Amsterdam: Academic Press 37: 103-127.

- Gould KS (2004) Nature's Swiss Army Knife: The Diverse Protective Roles of Anthocyanins in Leaves. J Biomed Biotechnol 5: 314-320.

- Luo Q, Alomgir MD, Sameen D, Ahmed S, Dai J, et al. (2021) Recent advances in the fabrication of pH-sensitive indicators films and their application for food quality evaluation. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr 63: 1-17.

- Pereira AC, Juliana BS, Renato G, Gabriel ARM, Isabela GV (2011) Flower color change accelerated by bee pollination in Tibouchina (Melastomataceae), Flora - Morphology, Distribution, Functional Ecology of Plants 206(5): 491-497.

- Chalker SL (1999) Environmental significance of anthocyanins in plant stress responses. Photochem Photobiol 70(1): 1-9.